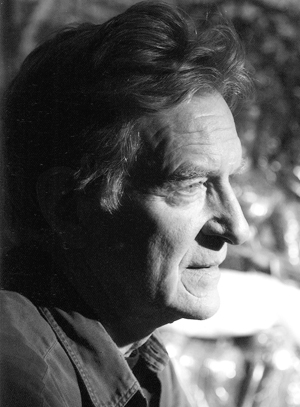

Guernica magazine has a new interview with Robert Thurman, once a Tibetan Buddhist monk and now professor of Buddhism at Columbia. He’s also co-founder of Tibet House and the father of actress Uma Thurman. Here, he discusses the prospects of a new world order based on nonviolence and the realistic—and perhaps even violent—steps it may take to get there. Guernica asks him a lot of the questions that are so often asked of folks advocating violence. His answers might surprise some; take, for example, how he replies to the familiar question of what to do when an invader comes into the house:

Guernica magazine has a new interview with Robert Thurman, once a Tibetan Buddhist monk and now professor of Buddhism at Columbia. He’s also co-founder of Tibet House and the father of actress Uma Thurman. Here, he discusses the prospects of a new world order based on nonviolence and the realistic—and perhaps even violent—steps it may take to get there. Guernica asks him a lot of the questions that are so often asked of folks advocating violence. His answers might surprise some; take, for example, how he replies to the familiar question of what to do when an invader comes into the house:

You have to oppose whoever it is. You have a right to defend yourself and you should try. But you should try to do it with minimal violence. For example, if you’re in a place where the breaking in is very, very likely, I guess you should be well trained in martial arts. You should be well armed and well trained about the arm, then hopefully not use it. Or if you have to use it, shoot for the legs. Be like Grasshopper, if you remember the old Carradine show Kung Fu. You should be forceful in opposing and defending, but without hatred.

It’s far from a pacifist position. The Tibetans didn’t violently resist the Chinese, he explains, not out of principle, but because they weren’t strong enough to be successful. If they had been strong enough, they would have practiced a restrained and defensive military campaign. “Buddhism is pragmatic; it’s not fanatic,” he says. “We have surgical violence within nonviolence.”

Despite the advice to keep a gun in the house, he’s a staunch advocate of demilitarization and imagines a global order based in detente toward nonviolence.

It would not be a Buddhist strategy, however, in the current moment on the planet to completely, unilaterally, and 100 percent disarm because then we could be pushed around by anybody. That’s not what’s being advocated. What’s being advocated is a genuine slow process of disarmament. I have a slogan. I call it shifting from MAD to MUD. It means switching from Mutual Assured Destruction to Mutual Unilateral Disarmament.

Thurman’s answer to another inevitable question—the one about opposing Hitler—insists, thankfully, that there may have been alternatives available to the bloodiest war in human history. The mistake people often make is to assume that a nonviolent solution should mean no suffering on either side. Thurman points out that the cost could be quite high, but almost certainly not so high as what actually took place.

People point to the Holocaust, but the Holocaust went on in the middle of the war and the war was not stopping it. And then you never know had there been nonviolent resistance what would have happened. Had the Germans killed a couple million in France and England and here and there before realizing there was no point in occupying any country because people in the country simply would not feed them, they wouldn’t work for them, they wouldn’t do anything even if they killed them, that might have saved how many total million that did die in the World War, maybe forty or fifty million. I don’t know the number. But a lot.

A key to Thurman’s thinking, according to the interviewer, is a sense of perpetual optimism. “What keeps you so optimistic?” she asks.

It’s a moral duty. What that means is that you have to shift focus, you have to up level. If you look only at the negative things that are going on—not that you shouldn’t look at them, you absolutely should because you have to do something about every single one of them—then they infect you with their negativity. You become angry and depressed and desperate, and then you’re going to react with negativity.

He grounds his answer in an anecdote from Gandhi:

An American woman who was his disciple said, “How do you avoid getting too depressed or hopeless and all this?” And Gandhi said, “What I do when something terrible like this happens is I reflect on the great mass of people in the country or even in the world.” There was this one place where two or three hundred people were shot by some British, and then there were fifteen or twenty police killed by a mob in such and such other town, and other bad things probably happened here and there, probably some murders in the country and a few things. But hundreds of millions of people cooked dinner for each other, helped each other washing the dishes, helped each other cross roads, brought water from a well, restrained themselves from feeling angry with their neighbor when they might have started a fight, calmed down in some situation where they could have escalated. The larger fabric of society involves people interacting with some degree of altruism and empathy for each other, some degree of self-restraint, or the whole place would be in flames.

It is this insight that we hope to draw from here at Waging Nonviolence. In the “Experiments with Truth” posts, we see day after day how much is really going on—in terms of nonviolent work for justice—that so rarely sees the light of ordinary news coverage.

One last thing. At the end, he recommends The China Study, an important recent book about diet. My mother’s crazy about it, so I feel a filial duty to pass that along as well.

It is in reality an incredible as well as beneficial section of info. I’m content that you simply discussed this useful information here. You need to continue being us educated such as this. Many thanks revealing.