The real-life experience of African nonviolent struggles was important for Martin Luther King, Jr., who drew knowledge and encouragement from the civil resistance of Africans in Ghana, Kenya, Zambia and elsewhere in their quests for independence from colonial rule. In 1957 he visited the Gold Coast (soon to be renamed Ghana), with Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., U.N. official Ralph Bunche and A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. All were to participate in the independence celebrations of Ghana as a new nation, where protracted nonviolent struggle had been pursued in seeking free elections. African nonviolent campaigns, significant in the early and mid-20th century, remain equally so in the 21st century. The rest of the world has a great deal to learn from such campaigns, especially thanks to the central roles of women in resistance and peacemaking.

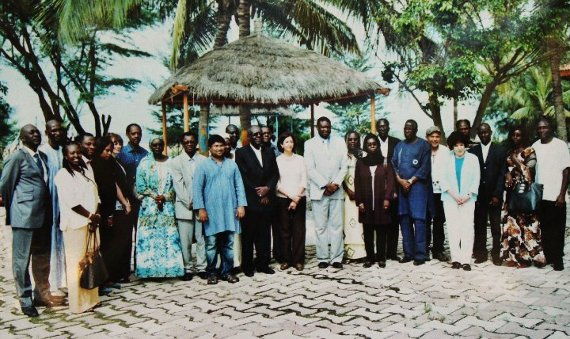

This coming year, along with Professor Oumar Ndongo, I’ll have the opportunity to teach a course on the nonviolent transformation of conflict for graduate students from Senegal and other parts of Africa at Université Cheikh Anta Diop, in Dakar, Senegal. He and I worked together in October 2012 at a small hotel in Mbodiène on the Atlantic coast, about 75 miles south of Dakar, the capital city of Senegal. We were among professors from Université Cheikh Anta Diop and the University for Peace, whose main campus is in Costa Rica. Together, we discussed our goals and examined each other’s syllabi, readings and teaching approaches.

The third and catalytic partner in the October meeting was Femmes Africa Solidarité, an organization led by Bineta Diop. In the late 1980s she led advocacy efforts for human rights education across Africa and subsequently has worked to bring the gender dimension onto the African governmental agenda.

For one week, all three partners worked to harmonize their policies and discuss how best to offer a new master’s degree in gender and peace building — an outgrowth of the growing recognition in recent decades of the futility of attempting to build peace without the full involvement of women. The program sits astride two streams of knowledge that have consolidated during the past decades: gender studies and peace building, both of which demand awareness of the theory and practice of nonviolent action.

Almost immediately, Oumar and I were on a first-name basis. Having earned two doctoral degrees for his research on the U.S. war in Vietnam, he is also an expert on the women’s nonviolent resistance of the Mano River Union countries in West Africa: Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. His studies of the hostilities in Southeast Asia allowed him to see the relevance of human agency, determination and ingenuity, including the use of nonviolent action for confronting the impressive arsenal of military weapons that the United States of America deployed to defeat Vietnamese resolve.

Imagine my delight to be co-teaching with an expert on the French and U.S. perdition in Indo-China, who is also a specialist on a contemporary example of women’s civil resistance! I learned from him that in the southern part of Senegal an old tradition recognizes what is called “village resistance.” During the second half of the 20th century, resistance to colonial rule became more and more centered on this village resistance — amid ongoing military struggle — due to land-grabbing actions by colonial administrations. Villagers resisted using nonviolent means such as sit-ins and the use of animistic rituals. It was quite common to have villagers deploy bees against colonial attacks.

The best known symbol of village resistance is the heroine and spiritual leader Aline Sitoe Diatta, also known as Alyn Sitoe Jata. During World War II, she led the tax-resistance movement against the French authorities, who seized half of the rice harvest from her community in the Casamance area for the war effort. Aline Sitoe Diatta organized the market women to boycott by not going to the market. In 1943 she was deported to Timbuktu — in Northern Mali, and today occupied by Islamist rebel groups. She died there in 1944.

Between 1989 and 2003, a deadly armed conflict spread across borders to overwhelm the West African region. It would become the most terrible humanitarian crisis ever to occur in that part of Africa. The conflict, which started with Liberia, swiftly spread to Sierra Leone and Guinea. As the result of poor resource management, corrupt practices, poor leadership and ethnic rivalries above all — particularly the arrogance of the Americo-Liberians, according to Oumar — all of the Mano River Union countries became drawn into the quagmire.

Between 2003 and 2005, Oumar was simultaneously studying and accompanying women activists of the Mano River Union to restore peace in the region. “Women were engaged in the war not merely as victims of the hostile actions of men,” Oumar stated, “but also as active combatants and perpetrators of violence.” Far more consequential for the ultimate outcome, however, were the women’s groups that took responsibility for ending the hostilities, with their horrific human toll. Of the many groups of women that became actively engaged in working to end the civil war, two stand out: Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET) and Women’s Peacebuilding Network (MARWOPNET).

WIPNET is a branch of WANEP — the West African Network in Peacebuilding, based in Accra, Ghana — and emphasized setting up its offices in countries throughout West Africa to report on the early signs of conflict and alert the Department of the Early Warning of the ECOWAS Commission in Abuja, Nigeria. The Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, is a regional economic community of 15 countries, established in 1975, which I visited with UPEACE colleagues in 2003.

In May 2000 in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, MARWOPNET was formed. Seeking to restore peace in a shattered region, the MARWOPNET network of women’s organizations from the Mano River Union brought together women leaders and representatives from local grassroots groups, who were able to spur an initiative that linked women from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea in committing themselves to pursuing a collective agenda of fostering peace and sustainable development for their respective countries and the region as a whole.

Liberia was home to especially strong groups whose use of nonviolent action played central roles in returning peace to that country. Among many notable actions, we can point to those of Liberian women at the peace talks in Akosombo, Ghana, where women exerted intense pressure on the warlords to sign a ceasefire document and end the war.

The 2011 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Leymah Gboweh stood out as a leading figure in using nonviolent means in this context. Undressing in the middle of a gathering of warlords was a critical moment in ending the war. In Liberian culture, it is a curse to her sons when a mother takes off her clothes and stands naked facing her children. This idea was to use this opprobrium as a scourge against all those who wanted to continue to wage war. The entire world learned of Gbowee’s work, as well as that of President Ellen Sirleaf Johnson, when they were awarded last year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

Other women resistance leaders have remained largely unknown, Oumar tells me. MARWOPNET’s Ruth Sando Perry and Theresa Leigh-Sherman, for instance, signed the Akosombo Peace Agreement in Ghana in 2003. A younger generation of activists has since also become engaged in transnational networks like WIPNET and WANEP.

For instance, women peacemakers from MARWOPNET and WANEP such as Lindora Howard, Ecoma Alaga and Cecilia Danuwelu have organized peace tours in the region and made periodic appeals to news media to bring warring factions to the negotiations table. The 50/50 Group in Sierra Leone, according to Oumar, with its chapters in many neighboring countries, is now promoting a long-term goal of gender equality and sustainable development. Other organizations include the Network of Women Parliamentarians and Ministers, which is seeking to promote women for community leadership. It has played a leadership role in stressing the need for women to have access to political positions.

An explosion of women’s nonviolent activism in Africa has been dynamic and creative, even though historically women have often been excluded from peace processes. According to Oumar, women’s militancy that was showcased by women-led organizations helped to end the 14 years of civil war.

Nonetheless, he is concerned for the future. “Across West Africa, the lack of formal education has severely limited women’s ability to attain key political positions,” he says. “Even where the educated women have decided to build structures to advance women’s interests, the challenge still persists.”

That’s where we come in. Our challenge will be to help our students — male and female — to see for themselves that comprehensive socio-political change with potential for reconciliation and transformation is more achievable with civil-resistance movements than with armed insurgency. Africans have contributed compellingly to our understanding of the link between gender and peace building and historically have been key protagonists in developing the technique of civil resistance. Oumar and I will take full advantage of the inherently comparative nature of studying nonviolent action. When combined with gender as a dynamic, cross-cutting tool for enabling a new generation of specialists to address age-old predicaments that have acted as impediments to building peace, Oumar and I may well learn as much as we teach.

Nice piece! Another heartening aspect of the work of Leymah Gbowee and her group was the multifaith nature of the movement that ousted Liberian dictator Charles Taylor, countering the dominant media narrative that Christianity and Islam are constantly at loggerheads in Africa.