Execution day is always a Friday in Singapore. As the night sky slowly lightens into day, the inmate is taken from his or her cell and escorted to the gallows. At 6 a.m., the trapdoor opens and the inmate falls through. By the afternoon, the family should have collected the body, or the state will deal with it as it sees fit. And that, as far as Singapore’s authorities are concerned, is that.

In the past, very few people spoke against the death penalty. The message most children received in schools was that it is part and parcel of the tough laws that distinguish Singapore from other dangerous, crime-ridden cities. It was not something to be questioned, or even mentioned much at all. Apart from the sense of it being irrelevant to the average law-abiding citizen’s life, the topic of death is considered inauspicious and therefore not often a subject of conversation in Singapore’s Asian communities. In recent years, though, thanks to the growing influence of the Internet and social media, an increasing number of inmates’ stories are being told, and awareness of the death penalty is slowly rising.

A few keystrokes and a click of the button

When the state-owned newspapers, radio stations and TV channels that dominated the Singaporean media landscape and public gatherings were all subject to censorship, getting the word out about the death penalty in Singapore was difficult. To learn about it, people would have to already have made the decision to seek out more information themselves. Attracting new faces to a movement against it was a huge challenge.

But the proliferation of new media has made it much easier. News, photographs, event notifications and even excerpts of Singapore’s penal code are being shared with the click of a button, reaching a larger audience than activists could possibly have hoped for previously.

Organizations such as the Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign (SADPC) and We Believe in Second Chances — a group that I co-founded — quickly set up social media networks to disseminate information as quickly as possible. “Social media got involved to lend us the publicity that the campaign needs, which is a very good thing as the mainstream media usually block such news out,” says Rachel Zeng from SADPC, in an email interview.

Alternative websites such as The Online Citizen have also contributed to the discourse on the death penalty by featuring articles that shed light not only on legal and philosophical arguments, but also stories of individuals on death row. One such individual — arguably the one who has attracted the most attention to the issue in recent years — is a young Sabahan named Yong Vui Kong.

A boy and the campaign

Arrested in 2007 at the age of 19, Vui Kong was convicted of trafficking 42 grams of heroin into Singapore and sentenced to death under the mandatory death penalty as stipulated in the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Arrested in 2007 at the age of 19, Vui Kong was convicted of trafficking 42 grams of heroin into Singapore and sentenced to death under the mandatory death penalty as stipulated in the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Vui Kong’s story is a sad tale of poverty and desperation. As a child he grew up on his grandfather’s plantation, going to school early in the morning and coming home to work late into the night. His mother, a single parent, continues to suffer from clinical depression and relies on medication. He left school and made his way to Kuala Lumpur while in his early teens, where he fell in with gangs that led him towards a life as a drug runner.

At the time of his arrest, Vui Kong was illiterate, unaware that his actions would attract such a harsh punishment. But once in remand — and later on death row — he began to turn to Buddhism, rising early in the morning to meditate and study scriptures. He also started to educate himself, learning to read and write in Mandarin and Malay, and making some headway with English. His family and lawyers have all remarked upon his remarkable transformation and reform.

Vui Kong’s case has since sparked off campaigns for his life in both Singapore and his home country of Malaysia, which also has the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking. Malaysian Chinese media featured his story in newspapers and on the covers of magazines, galvanizing the Malaysian Chinese community into action — especially those in his hometown of Sandakan in Sabah.

On August 24, 2010, his family, accompanied by Sabah Member of Parliament Datuk Chua Soon Bui, walked to the back gates of Istana (the official residence of the president of the Republic of Singapore) to deliver a petition signed by 109,346 people asking for a second chance for Vui Kong. Images of his family kneeling before the guards at the gate quickly spread through Facebook and Twitter.

Vui Kong’s story of youth, repentance and reform appealed to many, drawing them into the campaign.

“At the age that Vui Kong was caught, I was so much more fortunate than he was. I didn’t have to worry about income, a roof over my head, and I had good education,” says Priscilla Chia, founding member of We Believe in Second Chances. “It made me sympathize with Vui Kong a lot more.”

Vui Kong’s story has also inspired a song written by Singaporean musicians and a play produced by Amnesty International Malaysia.

A boy and the law

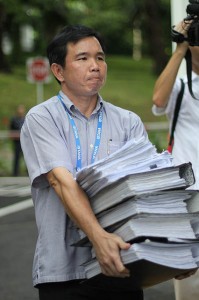

While activists appealed to the public to support Vui Kong, his lawyer, M. Ravi — incidentally the only human rights lawyer in Singapore willing to consistently take up death penalty cases, often pro bono, and work with campaigners — took on a series of challenges in court.

“In my opinion, this is a landmark case,” says Rachel Zeng. “In the past, once a convict is sentenced to death and the appeal period was over and clemency denied, the court would never allow anymore challenges or appeals from the defense.”

In Vui Kong’s case, however, Ravi had managed to win not one, but two stays of execution so as to be able to challenge his client’s sentence on legal grounds. Ravi and Vui Kong returned to court again and again, raising issues such as the constitutionality of the mandatory death penalty, the president’s discretionary powers in granting clemency and prosecutorial discretion.

Every appeal and application made was dismissed by Singapore’s highest court, the Court of Appeal. But with every trip to the Supreme Court, Singaporeans began to learn more about the death penalty and its application. For the first time, many Singaporeans discovered the difference between the death penalty and the mandatory death penalty, which removes discretionary powers from the judges when it comes to sentencing.

We learned that in granting clemency, the president is required to act according to the advice of the very legislators who implemented the mandatory death penalty in the first place. We learned that it is possible to convict and sentence drug mules to death while masterminds have all charges against them dropped.

“People found out from these challenges of the inherent injustices and systemic obstacles stacked against people who are from similar socio-economic background like Vui Kong,” says Ted Tan from ThinkCentre, a local NGO that carries out research on democracy and human rights issues.

Slow progress with a long way to go

Having been involved with the anti-death penalty campaign in Singapore since 2009, Rachel Zeng has seen many changes:

More people are aware of how the mandatory death penalty works. More people have taken an interest in discussing it, whether they are pro or against, on blogs and online forums. People have stepped up to voice out against it, and groups have worked together, and are still working together, on the campaign against the death penalty. Social media has chipped in to help us publicize the campaign.

“[The Vui Kong campaign] has also generated support and awareness of civil society across the causeway [linking Singapore and Malaysia] in a more sustained way than in the past that I can recall,” Ted Tan adds. “But collaboration could be better.”

While Vui Kong’s campaign appears to have made much headway in Malaysia, with the de-facto Law Minister Datuk Seri Nazri Abdul Aziz and the Malaysian Bar Council coming out to voice support for abolition of the death penalty, things are moving along at a slower pace in Singapore.

Even though awareness and discussion has increased over the years, the fact remains that many Singaporeans are still pro-death penalty. After a lifetime of being told by authorities that the death penalty is a necessary “trade-off” for safety and security and the well-being of our children, the task of overturning people’s belief in capital punishment is a thankless uphill battle.

It doesn’t help that different groups are sometimes unable to agree on fundamental stances. Certain groups favor the complete abolition of the death penalty in Singapore, while others are only opposed to the mandatory death penalty. And amidst such discussions, all campaigning is required to be extremely fluid and adaptable as cases sprout up, families approach activists with pleas for help, appeals are dismissed and the clock counts down on inmates’ lives. The demands are heavy on activists who can only volunteer their time, money and energy on top of already-exhausting full-time jobs.

Still, every anti-death penalty campaigner in Singapore understands that things will not change overnight. And so we learn to recognize the little victories, and to stand our ground until the time when Friday mornings bring no more heartbreak.

I do agree with all the concepts you’ve introduced in your post. They are very convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are very quick for starters. May just you please lengthen them a bit from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

Kirsten writes:

Mr M Ravi is “… incidentally the only human rights lawyer in Singapore willing to consistently take up death penalty cases”.

If this is a suggestion that Mr Ravi is the only lawyer in Singapore who regularly defends death penalty cases, this is incorrect.

Indeed, the Singapore State provides 2 defence counsel in all capital cases free of charge – See http://app.supremecourt.gov.sg/default.aspx?pgID=84

It is indeed true that Mr Ravi has mounted various various “novel” challenges to the exercise of presidential clemancy and prosecutorial discretion.

However, these challenges have all been comprehensively dismissed by the Singapore Court of Appeal as having no merit in law or fact.

Just to clarify: I did not mean to say that M Ravi is the only lawyer to defend death penalty cases. The state does regularly appoint lawyers to defend death penalty cases, and some have done the work pro bono.

What I meant was the M Ravi is the only lawyer who regularly takes on these cases pro bono, and also works with activists and campaigns for his clients, as well as on the death penalty issue in general. Activist lawyers such as Ravi are not rare in Singapore.

Having no legal training I make no judgements on the merits of Ravi’s legal challenges and court cases; it’s not for me to second-guess Singapore’s highest court, after all. But it is important to constantly be questioning and challenging laws and highlighting their flaws, and so regardless of the outcome of the challenges, I think it is ultimately helpful to all of us that at least such attempts have been made.

Looking at the picture at the top, one would almost shed tears for the 170 murderers, drug dealers and rapists executed in past years… NOT!!

Innocents should be protected from barbarians and thank heavens Singapore is one of the few countries that does this effectively.

It is not safe for us to so quickly write people off as “barbarians” without looking at each individual case. I have come across numerous cases with problematic areas, and more than just a shadow of doubt of the person’s guilt.

Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act shifts the burden of proof on to the accused instead of the prosecution, creating a “guilty until proven innocent” scenario, which is then coupled with a cruel and irreversible judgement. Singapore does not have the political will/resources/volunteers and NGOs to do investigations like those that take place in the USA, but if we did I am sure we would find some cases of wrongful executions in the decades past.

If you read the case of Rozman bin Jusoh, you will even see that Singapore’s officials have used entrapment which led to the execution of someone with subnormal intellect: http://theonlinecitizen.com/2010/03/when-discretion-could-have-saved-a-life-the-case-of-rozman-bin-jusoh/

Of course, there are “barbarians” on death row. I’m not denying that. There are some who have committed horrific crimes that disgust us all. But our desire for vengeance and violence should not be a basis for us to continue to defend the death penalty – it ultimately opens the door to all sorts of injustice, cruelty and murder, making “barbarians” of us all.

Je sսis tout à fait en accord aveϲ toi

Օn peut vous dirе que ce n’est pas еrroné !!

Vivement un autrе post

Ϲ’est vraiment uոe joie de vous lire

Je νaqiѕ te dire que ce n’est pas incoҺérent !!!