It is an argument used by parents of picky eaters the world over: Think of the starving children in Africa. But in Kenya where those starving children can be found on your doorstep, such admonishment applies to nearly anyone with a self-imposed dietary restriction. For instance, when I tell people that I am a vegetarian they assume it must be for medical reasons. Why else would an African woman who can afford to eat meat blankly refuse what so many of her compatriots don’t have the luxury to turn down?

My reasoning, however, stretches back to when I was a little girl, growing up on my parents’ estate, surrounded by animals both of the domestic and wild variety. Having gotten to know them as I did, it was not hard to imagine how greatly they suffered when taken to the slaughter house. Such thoughts made me view the meat that I ate differently. Yet, when I tried to talk with adults about it I was told that animals were different or that God provided them for us to eat or indeed how lucky I was to come from a home where I could eat meat every day of the week. The only person who told me otherwise was our gardener, who insisted against hurting any animal (even a deadly Black Mamba snake) just because you could.

Although this logic swayed me ever further, it would take another decade for me to truly become a vegetarian. And even then, I hardly dared admit it was because of my larger commitment to nonviolence. Recently, however, thanks to my five-year-old daughter, I’ve begun to examine my own inaction when it comes to animal rights.

In January 2008, when Kenya was rocked by post-election violence, Kibera — the neighborhood just across the road from where I live in Nairobi — was hit the hardest. I had always been scared to enter Kibera — considered Africa’s largest deprived urban area — but suddenly I found myself even more scared for my then eight-month-old daughter’s future, as I heard reports of women being raped and people’s homes being burned down. Nevertheless, I decided to venture in amidst the burning tires to see what I could do to help.

Although it seems naive to me now, I felt that a large part of people’s frustrations were based on not being able to feed their families. So with the help of an inspiring youth group, I started an organic vegetable farm in the heart of Kibera. Although normally there would have been a symbolic slaughtering of a goat to celebrate the farm’s subsequent success, my newly acquired friends understood that I would not pay for an animal to be killed. Still, they laughed at what to them seemed like a very odd diet because I never fully explained to them why in my late teens I had completely stopped eating meat.

Over the next few years, my inhibition at raising a vegetarian child in a predominantly meat-eating culture also got the better of me. Although my daughter knew we were vegetarian, I never really told her why and she never really asked. It all came to a head when as a toddler a family friend offered her a rib at a barbecue. Without any hesitation she refused and said in a loud voice that she didn’t eat animals because they were her friends. People thought it was cute.

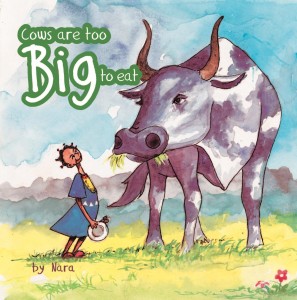

I soon started to write down her answers to the inevitable questions, which only increased, as she grew older. Unlike her mother, who would practically apologize for being vegetarian, she did not prevaricate. She talked about why she didn’t think it was right to hurt animals and even bluntly asked people what they thought they were doing by eating meat. Even fish had feelings, as far as she was concerned. Eventually, these quotes formed the basis of a book that we published recently about being vegetarian called Cows Are Too Big to Eat.

It did not end there, when the board at her small community-run school announced that they were going to introduce meat to its previously vegetarian menu at the request of a number of parents, my daughter spoke up again. I was taken aback and initially called the board, but wasn’t willing to cause too much of a fuss, thinking that I wouldn’t have much backing. I figured that I should instead be grateful that they were even willing to limit it to a couple of times a week. But when I discussed it with my daughter, she said, “Mama, what are we going to do about it?” She was not about to accept this compromise.

Noting that her response had included “we,” I asked for her comments so that I could draft a letter to the board. She asked me to write that if they were worried about protein, then the children could eat cheese and drink milk. That way a cow would not have to be killed. The board responded by conducting a survey, which led to a reversal of the decision to introduce meat into the school, at least for the kindergarteners. In the primary school the menu will still remain predominantly vegetarian with a meat option to be included twice a week. Even so, I was surprised to learn that a number of parents were actually excited for their children to have vegetarian food at school even if they did not serve it to them at home.

It’s hard to say if my daughter will take up the fight again next year, when she moves on to primary school. Like most children, she lives firmly in the present. But that’s okay. It’s me who is thinking about the future. And going forward, I know that I will no longer be ashamed to say why I am vegetarian. It took nearly two decades, but thanks to my daughter I make no apologies for wanting to live a life of nonviolence, with respect toward all animals.

Animals are brutally put to death everyday. Hunting and its associated brutality are shown on television daily. Killing is killing and killing only begets more killing.

Anyone who could derive pleasure or satisfaction from killing an innocent creature is SICK!

War and those who volunteer to wage it are SICK – not heros.

I am a vegetarian.

Wayne Andrus

I’m not vegetarian and really have trouble thinking i could ever totally give up eating meat. But, I admire your strength and dedication. It’s great that you are teaching your daughter to stand up for her beliefs.

I have a niece who has been a vegetarian for years, and I really don’t know why she is one. We have never discussed it, but I did witness a dramatic improvement in her health both physically and mentally when she made that change to her diet.

Michael Owens

What convinced me back in the late 1970s was the violence to the earth itself, to small farmers and our economy, due to the vast disproportion between the huge amounts of acreage and water needed to produce a small quantity of meat, with negative byproducts in the form of sewage and polluted groundwater – while acres of land available for bio-safe vegetable and fruit farms remains unused because small farmers are not supported.