Egyptians took to the streets on Saturday to mark the one-year anniversary of Mubarak’s fall and launch a new campaign of civil disobedience aimed at bringing down the military rulers now in power. But a poor turnout exposed the country’s lingering divisions and left many wondering whether the revolution will ever be completed.

The answer might be found thousands of miles away, in the Maldives—a small Muslim nation in the middle of the Indian Ocean. This tropical tourist destination for the rich and famous has seen a week of turmoil, after its only democratically- elected president was forced out of office on Tuesday in what he says was a coup by supporters of the deposed dictatorial regime.

President Mohamed Nasheed came to power in 2008, when he defeated the autocrat Maumoon Abdul Gayoom—who ruled the Maldives for 30 years—in a free election he helped force into existence by leading a massive popular campaign of nonviolent resistance. Prior to his victory, Nasheed had been a longtime pro-democracy activist, spending six years in jail and nearly two more in exile forming an oppositional party.

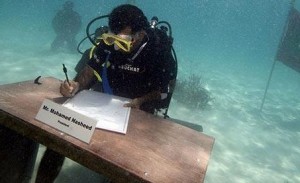

During his presidency, Nasheed became an internationally-recognized advocate for the climate movement—famously holding an underwater cabinet meeting to draw attention to the rising sea levels threatening his homeland. He also pledged to make the Maldives the first carbon-neutral country by 2020 and urged thousands of demonstrators at the Copenhagen Climate Conference in 2009 to continue protesting and the “process of movement building.”

During his presidency, Nasheed became an internationally-recognized advocate for the climate movement—famously holding an underwater cabinet meeting to draw attention to the rising sea levels threatening his homeland. He also pledged to make the Maldives the first carbon-neutral country by 2020 and urged thousands of demonstrators at the Copenhagen Climate Conference in 2009 to continue protesting and the “process of movement building.”

Despite such noble efforts, however, Nasheed’s presidency was, like any fledgling democracy, plagued with strife and shortcomings. As a Wikileaks cable revealed, Nasheed ultimately signed on to the controversial Copenhagen Accord in exchange for development aid after publicly criticizing the wealthy nations that drafted it. Meanwhile, at home he came under fire for selling off a lot of the country’s assets to foreign corporations, such as the only hospital and international airport.

The opposition, comprised of Gayoum supporters and Islamic extremists upset with Nasheed’s moderate outlook, capitalized on the public discontent by gaining more seats in parliament in 2010—with the goal of impeaching Nasheed. But he held strong for nearly two more years, until he was forced out of office at gunpoint last week.

The impetus to remove Nasheed from power by such force seems to have come from his decision to have the military arrest a judge, whom he accused of blocking multimillion-dollar corruption cases against members of Gayoum’s dictatorship. The opposition claimed that Nasheed had overstepped his powers and months of street protests followed, with Gayoum loyalists in the police force and military taking part. Not surprisingly, in the wake of all this, Nasheed’s vice president—who is now the president and likely conspired with the opposition—appointed leaders from Gayoum’s party, as well as several Islamists, to his cabinet in an effort to create what he calls a “unity” government.

The United States and Britain spent the weekend calling on Nasheed to join the proposed coalition, but he rejected the offer, insisting instead on early elections. “Only an early election will stabilize the country,” he told journalists on Saturday, promising that his party would emerge victorious.

Given the clear divisions in Maldivian society, it may be hard to say whether such an outcome could be expected. But the past several days have seen thousands of people voice their support for Nasheed in the streets of the capitol city, Malé. The outpouring may have even been enough to convince the United States to back off initial support of the coup and instead push for an independent investigation into the transfer of power, which the new government has now agreed to.

This small victory is a sign that the people still have the power, as they did in 2008, when they brought democracy to the Maldives. But of course many concerns linger, including ones that have implications for those countries that rose up during the Arab Spring.

One person who can speak to these concerns is Srdja Popovic, whose Center for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) in Belgrade worked with pro-democracy activists in the Maldives in the lead-up to the 2008 elections. According to Popovic, the role of the international community is hugely important.

“If they praise the new government based on police mutiny, the seizing of national television by police forces and the likely armed ‘persuasion’ of the president to step down, that will become the model for the future and send a powerful message to rest of the Muslim world,” he said. “If the Maldives couldn’t make it—Sunni moderates who rely on tourism—what might one expect for Egypt or Syria?”

Should, however, the international community broker some kind of deal between the two sides that includes early elections, it will be, as Popovic described it, a “blood transfusion for democracy in the Maldives—regardless of whether or not Nasheed wins the election.”

Getting to that point, will take the renewed commitment of Maldivians and continued pressure on international powers along the lines of what transpired over the weekend. But as Nasheed wrote in a New York Times op-ed last week, “let the Maldives be a lesson for aspiring democrats everywhere: the dictator can be removed in a day, but it can take years to stamp out the lingering remnants of his dictatorship.”

Great piece, Bryan! I am quoting from it in a web column I’m doing on the situation there.

Thanks Amit, I look forward to reading your take!

Really enjoyed your column, Amit—especially the insight into Nasheed’s faith and the role it played in his activism:

Here’s a really ugly “human interest” story about New York’s connection to the Maldives, titled “Ossining neighbors cheer former resident as new Maldives president.” Apparently Nasheed’s successor, who collaborated with the coup leaders, is a local hero, known for throwing great parties. According to the AP:

Um, yeah…

This is just crap. I am a Maldivian. Let me tell you, there is no organization in the Maldives called ‘Muslim Brotherhood”. It is clear you don’t know anything about Maldives.

Not really sure what you mean, Jan. I never mentioned the Muslim Brotherhood in my post.

The fundamental problem in the Maldives (as in Egypt), is massive, endemic corruption by a wealthy elite that had been firmly institutionalized under the old autocratic regime. Once genuine political democracy came (through a combination of internal civic protest, external pressure by the EU and other democratic powers, and Nasheed’s plausibility as a new leader), it was inevitable that transparency and accountability — without which democracy is impossible — would jeopardize the relationships between foreign investors and rich beneficiaries in the old system.

In Egypt, the chief reason that the Army’s commanders have developed a modus vivendi with the Islamist parties is that none of them benefits in the long term from a freely and fully competitive politics or economy. Continuing to suppress young activists, women, workers, Copts, human rights lawyers, and foreign democracy promoters (whose role has been overplayed) is in the interest of those who hold power now. The Army’s top generals accumulated wealth under Mubarak, and military institutions have long wielded power in Egypt not unlike they have in Pakistan. They probably fear, more than anything else, the rise to majority power of liberal secular democrats who would start using parliamentary powers to shine sunlight on the corrupt recesses of the old and continuing system. The same dynamic is likely to have been in play in the Maldives.

There is no such thing as a democratic “revolution”, much less a nonviolent coup or “regime change” accomplishing such a “revolution.” The transition to democracy involves long, patient weeding of the old, overgrown garden to make way for an entirely new system of public discourse, media and governance. If the people’s resistance helps force out an autocrat and that opens the door to genuine self-rule, the people have to remain forcefully organized on behalf of the long, difficult evolution toward authentic democracy — in any country where such a historic opening occurs.

That process was underway in the Maldives, and now there has been a serious setback. But it would be an equally serious mistake to assume that external powers hold the answer to overcoming this apparent coup. The missteps of the U.S. diplomat who barged in last week, making pronouncements and recommending steps forward, doesn’t augur well for the wisdom of American or any other external guidance. External powers are state-centric and value stability over anything else, including the rights of the people. The ushering out of Gayoum couldn’t have been accomplished without the pressure of the Maldivian people. The retracking of democratization in the Maldives has to be driven by the same steady but relentless (and nonviolent) pressure.

Thanks Tom, I appreciate you stressing the point that it would be a mistake to say the power to overcome the coup lies in external powers. I might have made that a little clearer myself in the post.