There was much fanfare when a new solar-heated building opened for business in the up-and-coming Brooklyn neighborhood of Carroll Gardens last month. The five-story retrofitted complex houses a bed and breakfast and a Philly cheesesteak joint. Powered by wind and solar, it is expected to generate about 25 percent more energy than it uses. The developer, a company called Voltaic Solaire, has heralded the green building as the wave of the future, an energy-efficient model that can be used across the country. They have been giving tours to contractors and developers, and recently signed eight consulting contracts with other firms undertaking similar ventures.

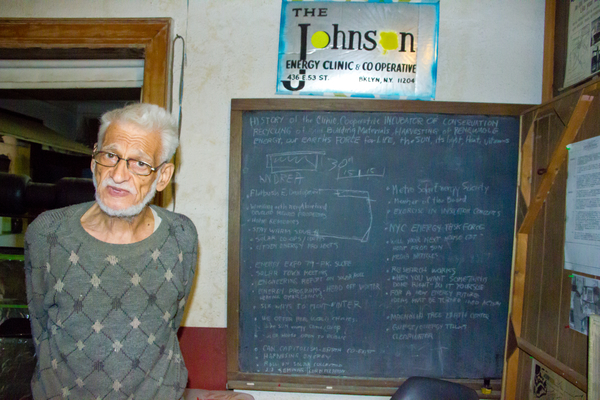

Meanwhile, on the other side of Brooklyn, in the not so up-and-coming neighborhood of East Flatbush, what is perhaps New York’s first solar home is facing foreclosure. Its owner, Jerome Johnson, a man who devoted his entire life to “solving problems” as he puts it, lives alone in the building that was once a thriving community workshop, surrounded by his inventions and the documents he has collected over his 82 years.

Binders full of newspaper clippings, brochures and correspondences tell the story of his life and the renewable energy renaissance that America underwent during the oil crisis of the 1970s. The complete annals of the New York Solar Society line Johnson’s shelves along with a plethora of magazines devoted entirely to wind energy, solar energy and green housing development. You’ll also find press clippings that trace back to Johnson’s days working as a top designer of studio lighting equipment in the 1950s and ’60s, his founding of the Johnson Solar Energy Cooperative in 1979, and on up to the present.

In the years before he established the cooperative, Johnson went through a difficult divorce. He admits that he even became a “ski bum” for a while. But then the energy crisis of the 1970s hit, when oil-producing nations in the Middle East decided to band together and set prices for themselves, rather than simply allow Western importers to milk them of their resources at fire-sale prices. As costs rose at the pump, Americans became curious about alternative sources of energy and Johnson saw an opportunity to put to use the skills he had developed tweaking lighting equipment for Hollywood and high-fashion photographers.

Johnson’s fascination with solar energy began in the early ’60s, when a client of his climbed Mount Everest for National Geographic magazine. All out of propane and freezing cold on the mountain, one of the climbers’ Sherpa guides suggested that they use the silver-lined photographic umbrella that Johnson had invented to disperse light for a more practical purpose; to capture the reflection of the sun and keep warm. When his client recounted the story it occurred to Johnson that his skill at manipulating light could be used to channel the sun’s energy. Back in his workshop, Johnson attached a mini-grill to his umbrella along with a rod to channel the sun’s heat, thus inventing one of the first modern solar cookers.

During the energy crisis, America also went through a major recession brought on by a stock market crash in 1973. In New York City the fallout was particularly severe. Firefighters and teachers were laid off en masse. “There were boarded up windows all over the place,” recalls Johnson. “People were losing their homes.”

When rising crime and economic deterioration drove Johnson’s ex-wife and children from the family home, he set up shop. Turning the old house into a workshop, he made the pre-World War I structure into a “research center.” He recalls, “People brought their ideas here and we executed them. Volunteers did the work. Everyone was learning.” Johnson’s neighbors pitched in and local businesses donated materials.

With the help of the community, Johnson affixed solar panels to the roof of the house. Rather than installing new pipes when old ones burst, Johnson set up a rainwater capture system, adjusting standard drainpipes to fit his needs. For additional heating and cooking, Johnson and his helpers salvaged old propane tanks and converted them into wood stoves. The spokes of old bicycle wheels helped catch the wind and generated further electricity for the building.

The laboratory Johnson built for alternative power also became a source of neighborhood empowerment. Children and teenagers would stop by after school to get their hands dirty or simply to play checkers with Johnson in the garden. “Otherwise,” he says, “these kids were going to get locked up.” Neighborhood housewives would also stop by and ask for his advice on home improvements.

On the weekends Johnson would give tours and lectures at the home. Thousands flocked to the house each year to witness the the latest scrap-part innovation Johnson was concocting and to maybe chip in a little and learn something. Afterwards, with all the visitors gone, Johnson and a small coterie of his friends and apprentices would linger together as the sun set. They would eat and drink and sit, prophesying about the possibilities that the sun, wind and human ingenuity had in store for the future.

Today, visitors no longer flock to Jerome Johnson’s house, but the bottles he emptied with his friends over the years line its glass walls; there’s cognac, brandy, and a bottle of Aunt Jemima pancake syrup. They are different colors and sizes, and when the sun hits them a kaleidoscope of light fills the home.

Aside from renewable energy literature and the minutes of the New York Solar Society, another kind of reading material has gradually begun to take up more shelf space on Johnson’s walls. These have to do with the tens of thousands of dollars that the City of New York claims Johnson owes in property taxes and water bills. Johnson, however, says he is eligible for a Senior Citizen Homeowners’ Exemption which would cancel or greatly reduce the debt he allegedly owes.

As for the water bill, which amounts to more than $20,000, Johnson hasn’t had city water flow through his pipes since 1982, when he and his helpers installed a rainwater capture system. When Johnson pointed out to the Department of Environmental Preservation that there is no water meter attached to the house, he was accused of stealing it. They also claim that he uses 250 gallons a month.

“I showed the letter that said how much I owed to the guy who runs the laundromat around the corner,” Johnson says. “And he said he doesn’t even use that much water.”

There’s a poster in Johnson’s hallway that features a photograph of a forest at twilight. The inscription on it reads: “Happy are those who dream dreams and are ready to pay the price to make them come true.” But the threat of losing his home and his life’s work has caused such anxiety for Johnson that it’s hard to believe that statement is true.

Johnson lives almost entirely off the grid and yet now spends much of his time haggling with the city’s bureaucracy and staving off a Virginia finance company that purchased at lien on his property.

He is not alone. Today, as in the era when Johnson first formed the cooperative, whole blocks of homes are being nailed shut across the United States. There were nearly 5,000 foreclosures in Brooklyn last year alone and housing advocacy nonprofits are facing funding cuts. According to Picture the Homeless, there are currently more empty dwellings in New York than there are people without roofs over their heads. The elderly have been hit hardest by the foreclosure crisis, with one in 30 Americans over 80 under threat of losing their homes.

As in the ’70s, we are again facing an energy crisis — albeit one of a different sort. While the United States’ supply of oil and natural gas is bountiful, our reliance on fossil fuels, which emit gigatons of carbon into the atmosphere every year, threatens civilization itself. If we continue on this path, it won’t be just people’s homes facing foreclosure, but Earth itself.

Meanwhile, the new Bank of America Tower in Midtown Manhattan, whose namesake pumped $6.2 billion into the U.S. coal industry over the last two years, implements many of the design features Johnson pioneered decades ago. The 50-some-story tower includes a rainwater capture system and insulated windows to trap heat. It is constructed partially out of recycled materials. Yet, in all likelihood, none of the smartly-dressed people drifting in and out of the building would recognize Johnson’s name.

Clean energy investments are down 54 percent from this quarter last year, but green capitalism has carved out for itself a niche market. These days, those who have capital to throw around are getting rich, peddling everything from solar panels to eco-friendly diapers. Not Johnson. He remains hunkered down at his East Flatbush homestead, living off of his monthly $650 Social Security check and fighting to preserve his life’s work.

Delmore Shwartz, a writer who chronicled the plight of those growing up during the Great Depression once wrote, “With dreams begin responsibilities.” But for Johnson, responsibilities to his community and to the Earth begat dreams.

More than 30 years ago, Johnson saw an energy crisis in his country and a social crisis in his neighborhood, so he tried to transform the lives of those around him by creating a model for another kind of world. A whole new generation taking up that challenge owes Johnson a tremendous debt.

Some discussion from Facebook:

Tina Badger: Is anyone doing anything to help save this man’s home?

Peter Rugh: Colia Clark, a Green Party senate candidate has championed Jerome’s cause to some extent, and lots of individuals have tried to help in a personal capacity but that’s about all. Jerome also has a lawyer looking over his case. I suggested he get in touch with some housing advocacy groups but he seems wary and disheartened. I also suggested an eviction defense should it come to it, but he said that they would just come back after everyone is gone. Sometimes it is hard to find a ray of sunshine in circumstances like this. If anyone has suggestions put them out there. Also, Jerome is looking for someone to sit down and carefully go through all the documents he’s got having to do with his legal situation. If you have the time and expertise to do so, let me know.

It’s a bit hard to follow the legal problems from the story. Also, for not knowing the Eastern US, I can’t picture the type of house or its surroundings. No water meter, but he gets billed for water use? Even understanding a property with a water hookup, but no meter sounds strange.

Inventor not seeking gobs of money for his efforts? If we had a humane society, with a humane government, a mutually beneficial society, the man would be valued much more. Case in point:

Had a local flood-a house got flooded. Developer and government failed to address this potential problem. Currently, the water collects and floods this one house, because a road blocks the flow of the water. The culvert installed was locked (why the lock, I don’t know) but even unlocked, the water once on the other side of the road had no where to go.

I calculated our surrounding storm ditches would have held a large portion of the water that flooded the house, if at each property line a small rock barrier where installed to retain a portion of the water in the ditch (sequential series of holding ponds) without any ill effects to the surrounding properties.

The plan went nowhere; I’m not an official engineer, so practical knowledge does not count in our society today. Anyone who played in the gutters as a kid knows water and how to alter its flow. Practical knowledge backed by years of experience, successfully that is, is shunned, ignored, and marginalized.

And this is America, what the old and smart of the third world do.where is Bill Gates and Opera.when are they going to open their Gates.i can not believe it, but it is a great lesson for theb world to learn from.let J,feel at reast for god is watching.Tears!!

TALKING with Mr. Johnson about this article, he informs of a mistake that reports the bill as 250 gallons a day, NO! He is being unfairly and incorrectly billed 250 gallons a day! (30 days times that, is250x30= 7,500 gallons a month is absolutely absurd even for a big business building full of restaurants, he lives alone and recycles his water without any meter on the old house) The bureacratic snafu (& journalistic report) is haywire!