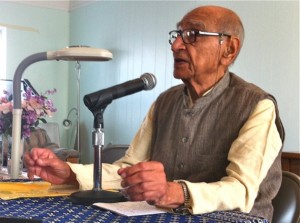

As I flew in from Illinois, the thunderstorms over Birmingham cleared long enough to let us land in good order. I had come to Alabama to attend a retreat featuring Narayan Desai, one of the last living disciples of Mohandas Gandhi, who made the trip there from India at the invitation of longtime activists and authors Shelley and Jim Douglass. Born in 1924 in Gandhi’s ashram, Desai has consistently undertaken Gandhian work for eight decades, and has recently published a 2,300-page biography of Gandhi. It was not only deeply moving to spend three days last week in the presence of this life-long Gandhian, but to do so in Birmingham, the site of one of the civil rights movement’s most iconic struggles.

As I flew in from Illinois, the thunderstorms over Birmingham cleared long enough to let us land in good order. I had come to Alabama to attend a retreat featuring Narayan Desai, one of the last living disciples of Mohandas Gandhi, who made the trip there from India at the invitation of longtime activists and authors Shelley and Jim Douglass. Born in 1924 in Gandhi’s ashram, Desai has consistently undertaken Gandhian work for eight decades, and has recently published a 2,300-page biography of Gandhi. It was not only deeply moving to spend three days last week in the presence of this life-long Gandhian, but to do so in Birmingham, the site of one of the civil rights movement’s most iconic struggles.

Even as several friends and I were collected at the airport and driven to the retreat center, I was vividly aware with each passing mile that we were traversing holy ground. This terrain resounds with a process for freedom set in motion a half century ago: a decision by African-American children, women and men to join together in concerted and bold nonviolent resistance for full and equal participation in society.

I believe that places where human beings band together for transformative justice become sites of enduring power. I first felt this in the 1990s when I was part of a bicultural team leading nonviolence retreats with Latino youths in California’s Central Valley. The land itself seemed imbued with the determination, courage and creativity of the migrant poor who, against very long odds, built the United Farm Workers and engaged in protracted — but ultimately successful — strikes and campaigns that sought the right to organize, increased wages and improved working conditions. In celebrating what would have been César Chávez’s 85th birthday this Saturday, we also honor the thousands who took action with him in the fields. This is only one of many struggles around the world that not only worked for concrete outcomes but left a legacy that seems to inhere in the land itself.

Such an inheritance can reframe how we see such land: from a terrain of oppression to a topography of liberation. This alternative overlay doesn’t erase the facts of injustice. Rather, it retrieves and holds dear the creative and stubborn ways injustice has been challenged through time. I suspect that virtually every acre on earth has not only been subject to domination and injustice, but also to struggles for justice. One of our jobs as agents of change is to rescue the memory of this seen and unseen resistance.

Birmingham has done this through the magnificent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which captures the history of oppression that the self-styled Magic City lived for decades, as well as the intricate details of a movement for nonviolent change that rose up to challenge it. The museum is situated directly across the street from the 16th Avenue Baptist Church, where four little girls — Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley — died when the church was bombed on September 15, 1963. During the pivotal Birmingham campaign that took place earlier that year, thousands of young people gathered in that same church and headed out to make history. In watching films over the years from that momentous protest, I had somehow thought that they had processed quite a ways before meeting the police. I was wrong; directly across the street is Kelly Ingram Park, where a storm of water cannons and German shepherds was turned on the youth of the city. The park is now studded with sculptures and statues memorializing the turning point that in many ways helped re-map Birmingham and the nation.

Gandhi’s Indian independence movement was also about re-mapping: transforming a terrain of colonial conquest to a nation under self-rule. Over the weekend, Narayan Desai shared his experience of this geographical and spiritual re-inscription. The three gifts of Gandhi that Desai illuminated were ashram observances (the vows and principles that Gandhi developed and served as the source for action, by which one can “convert personal virtues into social values”), the constructive program (18 comprehensive social programs), and Satyagraha (soul-force, truth-force and love-force activated for nonviolent social change). In both constructing new institutions and organizing many large and small Satyagraha campaigns — including the 240-mile Salt March in 1930 — the Gandhian movement was slowly reframing how one saw and understood India.

As we know, the power of this re-mapping went far beyond the Subcontinent. In the U.S., Gandhi’s vision and practice inspired numerous key figures in the civil rights movement, including Howard Thurman, Bayard Rustin and James Lawson. A few years after the Montgomery Bus Boycott, where Gandhi’s ideas had been seminal, Martin Luther King Jr. journeyed to India to immerse himself even more fully in Gandhi’s vision of soul-force. Gandhi’s grandson Arun Gandhi tells the story that, during this trip, King visited a museum which had previously been a private home where Gandhi often stayed. During the tour, King became fascinated with the sparse room where Gandhi slept and abruptly announced that he would be spending the night there. The museum official showing him around was bewildered and resistant. No one was allowed to stay in this room, he told his guest; besides, there were no amenities for him here. But King insisted and, after the official made a call to his superiors in the Indian government, he prevailed.

Apparently, King was eager to make contact with the spirit of Gandhi as he prepared for the next phase of his work. Just before leaving India, Dr. King was interviewed on national radio, and he said:

Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense, Mahatma Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation.

Just as King seized the opportunity to grow closer to Gandhi during his Indian pilgrimage, those of us who were in Birmingham last week had a chance to grow a bit closer to him through Narayan Desai, as we prepare for the next phase of our work for a nonviolent world.

For decades, Desai has carried on Gandhi’s mission in many ways — such as collecting three million acres of land for the poor as part of Vinobe Bhave’s Land Gift movement, and organizing Gandhi’s Shanti Sena or “Peace Army” along the northern border when there were tensions with China — but, after being in his presence for a few days, it seemed to me that he has done this most profoundly by, over many decades, imbiding and sharing Gandhi’s spirit.

Lovely piece! I agree that Desai has “inherited” the spirit of Gandhi, in all the ways suggested here plus one; Narayan goes about the world with a sly and challenging sense of humor which underscores the idea that life-long commitment to social change can and should also be fun. Desai was once asked by a group of US-based trainers how long the ideal nonviolence training should last. We were faced with growing pressures to make our workshops in preparation for civil disobedience ever-shorter (sometimes two hours or less) to adapt to the needs of an urgent pre-action moment. The ideal nonviolence training?, Desai reflected. In India, he suggested, many good ones last for years, but the really ideal ones last far longer than that!