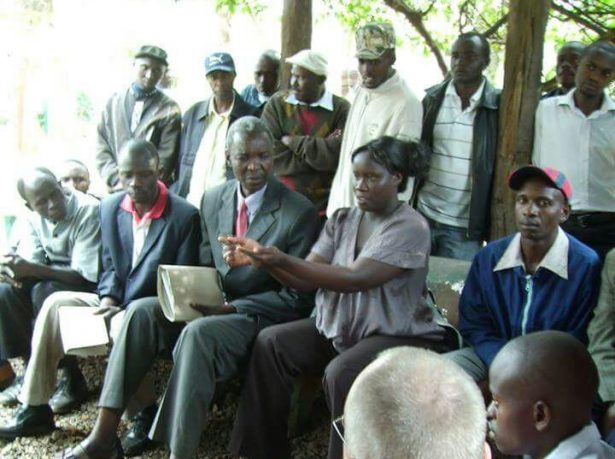

Kenyans concerned with social and political issues in their country gather in circles in public parks, standing in whatever space they can find, under the banner of Bunge la Mwananchi, or the People’s Parliament. Their evening public meetings open up dialogue and organizing opportunities as part of the group’s bottom-up structure for collaborative governance and cooperation.

Usually the police don’t disturb them. In the lead up to the August 8 presidential elections, however, the security apparatus cracked down on public debates and discussions, arresting a number of participants.

Raids on formal civil society organizations focusing on human rights and good governance themes continued even after the elections. Uhuru Kenyatta, the incumbent president, continues to harm any institutions critical of his brutality and fraudulent hold on power.

Forming in 1991, as global neoliberalism accelerated, the unemployed and underemployed allied themselves with other marginalized Kenyans to resist the privatization schemes of then-dictator Daniel arap Moi. They founded Bunge la Mwananchi, or BLM. Their movement grew through public education sessions and debates, where they discussed African liberation movements and the various social and political ills that they had been successful in confronting.

“BLM provides people with a platform to meet and discuss issues of governance, human rights and social justice,” said Wilfred Olal, who coordinates a campaign against extrajudicial killings by police. “We provide the space for activism for all Kenyans.”

At these meetings, the movement would utilize public parks. According to Gacheke Gachihi, a BLM coordinator, “The debates and lectures in the park were conducted on two benches that were facing each other, under the shade of a tree, giving it an organic feel.” Elders from the Mau Mau resistance to British colonial rule would also attend to enrich the dialogue.

A number of allied movements were strengthened by this popular education approach, and they began using a variety of tactics, such as occupations and marches, to prevent land grabs, secure the release of political prisoners, and make other advances against the Moi dictatorship, which was eventually pushed out of power in 2002.

In the years between then and now, however, neoliberalism — protected by the iron fist of the state — has again taken root. With the friendship of Barack Obama and other Western and Eastern powers, the global north has sent a message to Kenyatta’s government that human rights abuses can continue as long as the commercial environment is favorable for investment. This political back-scratching allowed Kenyatta, with brutality, to steal last month’s presidential election.

Kenyans are nonetheless speaking out against Kenyatta’s bloody coup, which was annulled by Kenya’s Supreme Court on Sept. 1.

The predictability of elections

Kenya was not the only East African country to suffer a stolen election last month. Rwanda’s Paul Kagame reinstated himself just four days before Kenyatta’s own self-appointment.

Electoral processes across the region have become predictable. Those clinging to the thread of hope between themselves and permanent cynicism queue at the polls. The votes are “tallied” independently of any actual ballot count. Opposition parties and international vote monitors condemn irregularities and the violence meted out by an incumbent. The judiciary is bribed and intimidated, backing down from any fight, while foreign governments refuse to leverage any influence they have.

The international media is unfortunately no more an ally to East African movements like BLM. Their chief aim was to dig for stories of “post-election violence,” painting a bloody picture of Africa and entrenching the belief that no democratic structures exist. BLM and similar activist groups were conveniently omitted from the global narrative despite their fierce determination in resisting Kenyatta’s coup.

Even in the quintessential democracies of the world, we are witnessing a rise in distrust toward voting as a means of substantial change. Countries founded centuries ago on core democratic ideals are faltering.

How can we then expect young countries — founded in disregard of their indigenous governance systems a mere half century ago — to adequately replicate expensive foreign systems that are broken by design? Somehow we expect them to produce results that benefit the majority of their populations.

The brand of democracy that characterizes East Africa is not working. In the August 4 election, Kagame, Rwanda’s de facto leader since the genocide of 1994, claimed to have won nearly 99 percent of the vote. Those who refused to vote for him routinely face harsh consequences: prison, exile or worse. Journalists who live to tell about it are blacklisted by the state.

Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya’s incumbent, claimed a more modest figure of 54 percent of the August 8 vote, but his tactics have been comparably draconian, with dozens of opposition supporters killed since election day as state security continues targeting dissidents.

“Nearly 50 Luo Kenyans have been shot for demonstrating against the election results,” Olal said. “The government has also threatened to shut down two human rights organizations.”

Given the wasted money and dashed hopes of these performance elections, there’s an argument that it might be better for these leaders to simply declare themselves dictator for life. This would offer a lighter financial burden for their taxpayers. Dictators refrain from doing this, however, because their regimes are economically padded by the more democratic societies in the global north who prefer to see at least the instruments of democracy — however dysfunctional they may be — before offering financial aid.

Insufficient alternatives

East Africans also find little hope in their opposition figures due to their similarities to the incumbent or the extremely squelched political space in their countries.

For example, Rwandese opposition candidate Frank Habineza’s Democratic Green Party made six unsuccessful attempts to register and run against Kagame. Habineza’s running mate in the 2010 election campaign was found beheaded. It appears that no candidate can stand against Kagame without a rising death toll.

Other East African opposition figures are simply cut from the same cloth as their opponents. Kizza Besigye fought alongside Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni in the National Resistance Army before Museveni took power. The two would later have a falling out. Besigye has stood against Museveni for four consecutive elections, without ever using any particularly creative or powerful strategy to ensure his vote is protected through popular struggle.

Raila Odinga, a three-time candidate for Kenya’s presidency, was born in 1945. Although he might be a prefered candidate for freedom-loving Kenyans, he is substantially older than Kenyatta and has not put forth a new vision for Kenyan politics that holds enough power to challenge Kenyatta, even if he can win an actual majority of votes.

“The cycle is the same here: old versus old,” Olal said. “Politics have been made very expensive by corrupt old politicians who lock out the youth.”

The point is that partisan politics no longer holds water, if it ever did in East Africa. Transformation of the political system can only come by means of a popular struggle, which must be undertaken by young people living on the African continent — a continent that looks far different than it did when those now in power were young.

Infiltrate the system with unlikely politicians

While members of the old guard who have defected to opposition parties challenge their fellow elders in the political arena, some new players are stepping onto the field. Their election is beside the point, however, as they are using the platform to rally their constituents to employ peaceful resistance for their own liberation.

Consider Robert Kyagulanyi, known by his artist name Bobi Wine, the “Ghetto President.” Born in the slums of Kampala, Kyagulanyi has spent nearly his entire musical career advocating for change in Uganda. While most artists with his level of popularity sell themselves as mouthpieces for the ruling party, he has stood firmly behind his lyrics, criticizing those who prolong their stays in power.

In April, Kyagulanyi announced his intentions to run for a parliamentary seat as an independent. With ease, he defeated candidates from the ruling party and the leading opposition party, despite police interference during election day. Since his appointment, he has mobilized great crowds, even in more rural towns, advocating for peaceful resistance against the Museveni regime.

Few artists or activists pursue formal politics, but often those who do utilize the space for purposes of mobilization. Their point is often not to say that they will faithfully and humbly represent their constituents, but that their constituents are capable of representing themselves by building collective power.

Popular struggle without a charismatic leader

A new type of politician is not enough. After generations of living under dictatorships, patriarchy and gerontocracy, a culture of “let the big man handle it” has become deeply rooted.

This is why a change in president is also insufficient. Assuming Kyagulanyi ousts Museveni in the years to come, other social factors might still dictate a reliance on leaders, on the people at the top. No one person can solve the problems facing any nation.

Nor is mere activation of the masses sufficient. There is a drastic difference between joining Kyagulanyi’s passing caravan and forming grassroots structures that offer longer-term platforms to resist oppression and build up alternatives. Charisma will get people to the streets today but will not usually offer strong possibilities for power tomorrow.

Democracy is best practiced in conflict. The following of leaders — as most ruling party and opposition politicians in East Africa would prefer it — cultivates something entirely contrary to real democracy. It fosters a system and political culture that is highly patriarchal and hierarchical.

East Africa’s youth must decide whether they want to organize collective resistance or be co-opted by their elders. Now that some of the groundwork of a movement infrastructure is in place, young people sick and tired of the options they have been handed are better equipped than before to rise up.