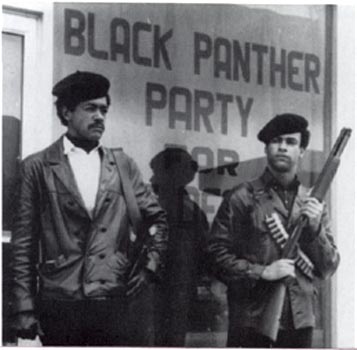

The Black Panther Party was an African-American radical organization founded in Oakland, California, in 1966. Originally it was called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, and even though it emerged in the North, it was responding to the same anger and frustration as the Deacons for Defense felt when watching black people get punished for standing up for themselves in the South.

The Panthers’ immediate goal was to protect black neighborhoods from police brutality. The group evolved from black nationalism to a broader revolutionary socialism. It rapidly expanded to many cities, still mainly in the North, and became influential. It differed from the Deacons for Defense in that it didn’t think of itself as a security force for the civil rights movement. Instead, it offered an outright alternative to the civil rights movement, with goals that included “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.” Its best-known programs were its armed citizens’ patrols to monitor the police, and Free Breakfast for School Children. Other programs included free medical clinics, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, and an experimental school to develop new methods for educating African-American children.

Not nearly enough notice has been taken of the Panthers’ effort, as a revolutionary organization, to include alternative institutions in their program. Many in the Occupy movement have made the same move. Both are in alignment with a framework that emphasizes “prefigurative work,” which builds skills and creates new ways for organizing life in a future society.

What drew more attention at the time, and still dominates the image of the Black Panthers, was their insistence on carrying weapons and their willingness to use them to defend the community. In 1967, for example, the party famously organized a march on the California state capitol, and the marchers openly carried rifles. So I was surprised in 1976 when two members of the Black Panther Party sat in my living room, which was filled with radical activists, and calmly stated that, looking back, they thought they’d made “a militarist error.”

Some of my friends protested: “You had the right to defend yourselves. Self-defense is enshrined in the Constitution! You weren’t saying you were arming yourselves to do revolutionary warfare!”

The Panthers on my sofa agreed with all of that, and said they were making a point about strategy, not about morality. Militarism, they said, is a point of view that makes violence more powerful than it really is. It makes carrying guns appear to outweigh the realities of color, and the intensity of white racism, and the vulnerability of the black community, and the nature of the racist mass media, and the strength of the apparatus of the modern security state.

Now, knowing about the U.S. government’s COINTELPRO program and its particular attention on groups like the Black Panthers, we see more easily what the two men were talking about. The Panthers’ moral claim to self-defense did not protect them, and carrying guns was a fact easily used as justification to wipe them out. Life isn’t fair, but then they knew that.

The strategic question is: Does defensive violence, or the threat of it, help us or hurt us as we struggle for justice? The inability of the Black Panther Party to protect even itself, much less to survive to protect the black community, speaks eloquently.

In 2012 we need to ask: What has changed since then, to make us believe that this time a strategy of armed self defense would work better than it did in the sixties? Has the national security state weakened in the meantime, its means of surveillance and infiltration become degraded? Has the 1 percent become more liberal, more interested in the well-being of all? Since the sixties, have potential allies become more attracted to violence as a means of struggling for justice?

I respect the Black Panthers’ launching a response in the North when the civil rights movement was reaching a point of self-evaluation, and that their response included creativity and an ideological inquiry. Note the mood of the period: By 1965, after 10 years of amazing victories in the most violently racist part of the country, the Deep South, many people in the North who identified with the movement carried mixed emotions. They felt disgust with the amount of suffering that it had taken to achieve those victories, and at the same time an expectation that those victories should by now have transformed America in a more profound way.

I was among the activists, both black and white, who toured the country in those days doing workshops at the request of local people. I remember an increasing number of complaints in the North: “Why hasn’t our situation changed in this community? Racism is going on just like before. All this nonviolent stuff and it’s still the same — maybe nonviolence doesn’t work!”

In response I would ask them to tell me about the direct action campaigns they themselves had waged in their communities. All too often the answer was, “Well, none yet.” Gandhi, tough old bird that he was, in my place would have asked, “You expected someone else to liberate you?”

I understood the complaint in cultural terms. From the national media coverage of the movement, Northerners could believe that this was a national movement about racism and poverty everywhere. Yes, to some degree it was national. But mainly it was a Southern movement focused on regional issues like that cup of coffee at a lunch counter and the right to vote.

Rather than wait for someone else to liberate them, the Black Panther Party started to act in the North. They found it hard going, but made some gains. Martin Luther King also turned to the North in that period, and began to address new challenges both culturally and politically. The nonviolent part of the civil rights movement saw some progress in the North, but found the intersection of race and class to be very tough, as did the Panthers. The Panthers added class struggle theory to help them, and King did so as well, only more slowly. (By the time he was killed, King was challenging capitalism as a system as well as building a cross-race, cross-class coalition to focus on poverty.)

From the point of view of the 1 percent, things were not going at all well in the mid-sixties. The machinations of the FBI to divide the civil rights movement weren’t very effective. The movement was growing and more people were raising a question that alarmed the 1 percent: Do we want a bigger piece of the American pie or does the pie itself need to be re-made? The country as a whole was polarizing; National Rifle Association membership was climbing as an expression of white anxiety. Escalating the war in Vietnam wasn’t working to marginalize the civil rights movement and restore overall unity, which was disappointing, considering that a historic function of war is to reduce internal divisions.

Still, the 1 percent had more cards to play. They could mount a bogus “War on Poverty” that co-opted smart young black organizers by giving them jobs in self-help agencies. (I heard Bayard Rustin say cynically, “It’s the first time the U.S. ever went to war with a BB gun.”) They could also make illegal drugs and weapons more easily available in Northern black neighborhoods, and it has been alleged that they did so.

Then the power-holders got a couple of big breaks. The civil rights movement itself divided over Black Power and the question of violence. The second big break came in the form of the riots that tore up people’s neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Detroit, Newark, Watts and elsewhere.

The movement stopped growing. White activist allies left for the more welcoming territory of anti-Vietnam war organizing, and emboldened racists took up their refrain once again but in the coded language of “law and order.” Because the movement lost the moral high ground, a minor bill introduced into Congress for an appropriation for urban rat control was openly laughed at in open session — an unthinkable act two years earlier. The urban ghetto doesn’t need rat control, said the attitude of the now-bolstered right wing, it needs more police and larger prisons!

The power-holders no longer needed to make significant concessions to the civil rights movement. The interest in armed self-defense and the flirtation with violence, beyond dividing the movement, went nowhere.

Left holding the bag most tragically were those black inner-city neighborhoods where the riots took place. A study found that, 40 years later, those neighborhoods across the country had still not fully regained lost ground. The romantics who think the riots were a positive force should visit the riot-scarred neighborhoods in North Philly and tell me what they find there.

Interesting comparisons are shown here. NRA vs. Black Panthers. Nice. The NRA lobbies against gun control. That is its primary objective… When the Panthers took to the street with guns to monitor police activity inner-city they were viewed as radicals. One has to admit the it does appear a little like anarchy. Yet, an important historical point goes missing. When an armed Black man carries a gun to protect himself against police brutality; one has to look at the still prevailing lack of power provided in the system today. I might add that as it was in the 60’s Blacks do not have much power against police brutality, guns or no guns. Our system just is not set up to enforce control over these events.

Great article about why violence, even in self defense, is not a good strategy for building a powerful movement.

Matt Meyer has responded to this article with remarks about the need for solidarity and nuance in approaching the Black Panthers: “Panthers, Pacifists and the Question of Self-Defense.”

Interesting how Lakey notes here that National Rifle Association membership grew in the mid-60s “as an expression of white anxiety.” This is a theme that Joan Burbick really explored in her brilliant book, “Gun Show Nation.” HIGHLY recommended:

http://www.amazon.com/Gun-Show-Nation-American-Democracy/dp/B005UW112E/ref=tmm_pap_title_0

I think Lakey’s strong, direct words here about the riots of that period, and the civil rights movement’s embrace of militarism, are important. They robbed the movement of its moral high ground and left it in ruins (along with several once-proud communities).

Anyone who believes in nonviolence should be tremendously invigorated by Lakey’s arguments.