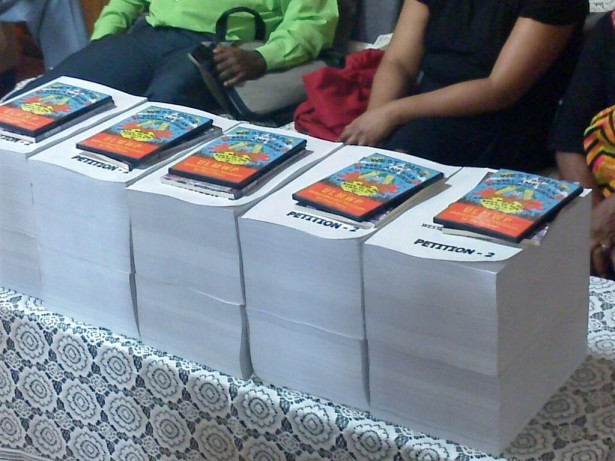

Markus Haluk’s eyes are moist. We are standing inside a portside warehouse in Honiara, the capital city of the Solomon Islands. Haluk carefully unwraps the first of five large 60 pound packages encased in hessian. Inside each parcel are two large A4-sized books, parts of a massive paper petition. Each book is around 16 inches thick — they make a dictionary look like a comic book. Haluk was the lead organizer tasked with collating the hefty tomes and getting them safely out of West Papua. Yosepa Alomang, a 50-something-year-old stalwart of the West Papuan independence movement, worked alongside him and she is also now in the warehouse. Alomang reaches out and touches the books. Turning to me she says, “These are the blood and bones of our people.”

Alomang means what she says. During the signature-raising campaign which took place between March and May 2015, Indonesian security forces shot dead 32-year-old Obangma Giban, a village chief from Yahukimo. In the month of May, alone, 487 activists were arrested for participating in the campaign. Some of those were tortured. Officers from the Mobile Police Brigade in Manokwari, part of a national Indonesian paramilitary police force, stubbed out cigarettes on Alexander Nekenem’s body while the head of the Manokwari Regional Police, Tommy H. Pontororing, denied him and his compatriots access to lawyers. Police also demolished communication posts at places like Cendrawasih University, where people could go to sign the petitions. Countless scores were savagely beaten.

The petitions are the latest nonviolent tactic in a struggle that spans more than 50 years. It is a fight that pits black-skinned, curly-haired Melanesians against their brown-skinned straight-haired Asian neighbors. Different people, different cultures and different histories forced together in an inequitable and unstable political arrangement. West Papua is the Pacific’s Palestine; greener and bluer, but occupied by the Indonesian military since 1963. It is a secret struggle, hidden by the Indonesian government, ignored by the international community, sold out by the United States and its allies. West Papuans were locked out of discussions over the transfer of sovereignty from the Dutch, West Papua’s former colonial ruler, to the Indonesian government by the Kennedy administration. The rights of the West Papuans were sidelined. It was Cold War politics with a silver lining for the United States. The deal delivered the world’s largest gold mine to Freeport-McMoRan, a private U.S. company, overseen by people like Henry Kissinger who sat on the board.

Seven years later, in 1969, the Indonesian government and United Nations colluded in a violent political fraud, the Act of Free Choice, involving 1,022 West Papuans intimidated into signing a document stating that they wished to join the Unitary Republic of Indonesia. Back then the world turned away. But now, in 2015, West Papuans are finding their voice, insisting their Melanesian neighbors in the Pacific recognize them as a nation-in-waiting, separate from Indonesia.

The paper petition is in support of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua’s campaign to become a member of the Melanesian Spearhead Group, or MSG — an important sub-regional forum, part of the Pacific Island Forum, and with status at the United Nations. MSG leaders were meeting in Honiara in June 2015. Gaining membership of the MSG is an important first step towards bringing the issue back to the United Nations, the organization that created the problem in the first place. Unsurprisingly, independence for West Papua, or even any discussion of the rights of West Papuans in an international forum, is vigorously resisted by the Indonesian government. There is a lot at stake: Indonesia’s reputation, West Papua’s massive resource wealth and the fate of a million and a half people.

While Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo was trying to reassure Melanesian leaders that Indonesia was a new democratic country, Indonesian police were undermining him. As West Papua seethed in unarmed insurrection, the security forces were desperately trying to violently pacify the population. But because of the Indonesian government’s ban on foreign media virtually no news of the petition campaign reached an international audience until the packages were carefully unwrapped in Honiara. The Indonesian government had tried to stop the petition from leaving the country, seizing copies at the airport as Papuan leaders attempted to take them to the Solomon Islands in their luggage. But Haluk, Alomang and the team had made several duplicates, sending them by different routes to Honiara. This package arrived by international courier. There are five copies, one for each Melanesian leader. Haluk tells me it cost a small fortune.

At a time when digital petitions land in our inbox every day, 55,555 signatures may not sound like much. But don’t be fooled. This is no collection of easy Facebook “likes.” Organizers with the United Liberation Movement for West Papua, or ULMWP, traveled the length and breadth of West Papua — by ship, plane, car and on foot — to collect the signatures from each of West Papua’s seven regions.

The petition not only includes the names, addresses and signatures of the petitioners, but people’s state-issued identification cards were also copied and included as further proof of authenticity. In addition to radical pro-independence Papuans, many Indonesian migrants also signed. Those who could not sign their name supplied a fingerprint. In addition, West Papuan leaders from all the mainline churches signed letters of support. So too did the National Council of Customary Chiefs in West Papua, or DAP, women and student groups, Papuan intellectuals, armed guerrilla groups and individual civil servants and politicians working for the Indonesian government.

The petitions, letters and the presence in Honiara of nearly 20 West Papuans from inside the country clearly demonstrate that ULMWP has deep and broad support inside the country. Papuan citizens may not have a country but they are the engine that is driving the ULMWP forward. And still there are tens of thousands of more petitions that did not make it to Honiara because they could not get them to the ULMWP work team in time to send the documents out of the country.

When ULMWP International Spokesperson Benny Wenda sees the petitions, he is emotional. “In 1969, the Indonesian government deceived the international community with 1,022 people who were forced to say they supported Indonesia,” he explained, referring to the fraudulent Act of Free Choice. “Today we have over 55,000 signatures.”

West Papua’s desire for freedom is the Indonesian government’s nightmare unraveling. That is why the police and military responded with such ferocity to the petition, a political act that has become routine and blasé in many countries. The rest of Indonesia may be a democracy, but in West Papua freedom of expression is prohibited. To the security forces, signing the petition is tantamount to sedition.

A herculean task

The ULMWP’s decision to focus on the MSG was important for external and internal reasons. Internally, the intermediate objective of securing membership in the MSG immediately became a vehicle for collective action — glue that bonded the newly formed organization together. Externally, West Papuan leaders knew there would be little international support for their cause unless their Melanesian kin and neighbors stood up for them. But gaining membership of the MSG was a herculean task. Not only did the ULMWP need to demonstrate massive support from inside the country, they also had to organize their efforts across five countries: Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Vanuatu and Kanaky, or New Caledonia. Moreover, they only had six months to do so.

This was not a level playing field. On one side was the Indonesian state with deep pockets, hard power at their disposal and the backing of the Papua New Guinean and Fijian governments. On the other was the ULMWP with limited financial resources, but increasingly organized people, with the support of the Vanuatu government, the Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front, or FLNKS, and the people of Melanesia. What was uncertain at the beginning of the campaign was how the government of the Solomon Islands would respond.

There was sympathy from people within the Solomon Islands government, but political representatives were starting with little knowledge about the reality of the occupation. Moreover, the previous Solomon Islands government had been courted by Indonesian officials eager to present a raft of economic development opportunities in return for political support. As the campaign progressed, the ULMWP was hindered by repression within West Papua, as well as externally by climatic disruption. Tropical Cyclone Pam devastated Vanuatu in March, leaving nearly half the country homeless. It completely destroyed the ULMWP’s administrative office and made it more difficult to draw on Vanuatu’s assistance to lobby other Melanesian leaders. Around this time Obangma Giban was shot dead as he organized a ULMWP fundraiser for humanitarian relief in Vanuatu.

Then there were the political challenges. Prime Minister Peter O’Neill from Papua New Guinea said a lot of nice words. He called West Papuans “brothers” and “kin,” but refused to meet with both Wenda and ULMWP General Secretary Octovianus Mote. In late March, O’Neill even went as far as deporting Wenda. In a somewhat embarrassing move for many Fijians, former military strongman, Prime Minister Voque “Frank” Bainimarama, pronounced on the front page of the Fiji Sun, his government’s mouthpiece, that the Indonesian government did not need to worry about their position on the ULMWP’s application: “Indonesia, we’re with you,” crooned Bainimarama.

Public records reveal that the Indonesian government invested $20 million to derail the ULMWP’s campaign. Fiji benefited handsomely. So too did Papua New Guinea. In the months before the MSG Leaders’ Summit, the Indonesian president and foreign minister criss-crossed Melanesia in their private jet. What deals were made behind closed doors is not known, but there was no way the Indonesian government wanted the ULMWP in the room. That is why they shot ULMWP activists dead in West Papua. It is why they jailed over 500 activists even as President Widodo announced he was freeing five, trying — and failing — to demonstrate that all was fine in West Papua. As far as the Indonesian government was concerned, West Papua was part of Indonesia. End of story.

Political machinations

It was always going to be a tough campaign. Then in the week before the leaders’ meeting in Honiara things got tougher. The pro-West Papuan government of Joe Natuman in Vanuatu was deposed in a no-confidence motion, ushering in Sato Kilman, a pro-Indonesian politician, whose previous election campaign was allegedly funded by the Indonesian government. The mood on social media in Vanuatu was ugly. The ULMWP leadership team met with representatives of the Vanuatu government. With less than a week before the Leaders’ Summit they were still unsure who would be representing that government in Honiara. The balance of power was shifting in the Indonesian government’s favor. Mote immediately embarked on an emergency diplomatic mission to Port Vila. Although he was assured that the Vanuatu government’s Wantok Blong Yumi Bill 2010 tethered governments of all stripes to enduring support for the liberation of West Papua, Prime Minister Kilman was unavailable to meet.

Then there were internal challenges. At a meeting in Port Vila in December 2014, when the ULMWP was formed, three large West Papuan coalitions of resistance groups came together: the West Papua National Coalition for Liberation, the National Federal Republic of West Papua, or NFRWP, and the National Parliament of West Papua. Immediately after the Port Vila meeting the President of the NFRWP, Forkorus Yaboisembut, withdrew his support for the ULMWP. As a parallel government pushing for international recognition of West Papua as an independent state, Yaboisembut argued that all groups should instead unite under the NFRWP. According to Yaboisembut, the NFRWP was both more representative and, as a government-in-waiting, had greater political authority than the ULMWP, which was formed as an umbrella organization.

I was part of a small delegation that met with Yaboisembut at his home in West Papua in February 2015. The three of us tried to explain what occurred in Port Vila, including the clear message that the MSG would not support an application for membership from a “government,” but there was no changing his mind. Yaboisembut announced that he would submit a new application for membership. The decision caused the NFRWP to split. The overwhelming majority of the NFRWP, including the West Papua National Authority and DAP, united under the leadership of Edison Waromi, who reiterated his support for ULMWP.

Political machinations continued. The Indonesian government, in an ambitious act of numerical contortion, announced that after years of criminalizing Melanesian identity, including killing West Papuan songwriters like Arnold Ap and Eddie Mofu for simply singing Papuan songs, that Indonesia was suddenly a Melanesian country. In fact, the Indonesian government boldly claimed they were the most Melanesian country in the world, with 11 million Melanesians — more than the entire population of the other five Melanesian countries combined. As a result, the Indonesian government argued, they needed to have their status as an observer of the MSG elevated to associate membership. To facilitate this they proposed that the five governors of Indonesia’s easternmost provinces would represent Indonesia at the MSG and duly submitted an application for associate membership. Franzalbert Joku masterminded the plan and O’Neill enthusiastically backed it.

The overwhelming majority of the population from the Indonesian government’s three recently discovered Melanesian provinces — North Malukus, South Malukus and Nusa Tenggara Timor provinces — are Muslim Malays, not Melanesian. I met the rather large Indonesian delegation in Honiara. There were only two Melanesians in the delegation, Franzalbert Joku and Nicholas Messett, and both are former pro-independence fighters now induced to travel the world as enthusiastic ambassadors for the Indonesian government. The rest of the delegation were Malay Indonesians.

Interestingly, the proposal that the five governors of eastern Indonesia represent the Indonesian government was not even supported by the governors of Papua Barat and Papua provinces, Indonesia’s only real Melanesian provinces. In a stunning act of non-cooperation, when President Widodo tried to meet with Lukas Enembe, the governor of Papua province, Enembe switched off his phone for three days. He told a trusted insider, who declined to be named, that “the MSG has nothing to do with me.” Both he and the Papua Barat Gov. Abraham Atururi refused to attend the MSG Leaders’ Summit. These two facts — the non-attendance of the West Papuan governors and the lie that Indonesia had a sprawling population of Melanesians — were quietly ignored by Papua New Guinea and Fiji. They embraced the governors’ application and argued against the ULMWP becoming full members, no doubt looking to benefit from the hundreds of millions of dollars of trade the Indonesian government promised.

A wave of solidarity builds

Meanwhile, Mote kept traveling while Wenda and the other three members of the ULMWP Secretariat kept meeting MSG officials and leaders. In June 2015, the governments of both Samoa and Tonga expressed support for freedom in West Papua and the ULMWP. West Papua was rapidly becoming a cause célèbre across the Pacific. While diplomacy with governments continued, it was grassroots support that created the incentive for political leaders to take a clearer position. And still a wave of solidarity was building.

In Fiji, where the Pacific Conference of Churches had its head office, the proliferation of support for the ULMWP required the formation of a solidarity council. The Pacific Conference of Churches also helped reignite solidarity in the Solomon Islands. In March they brought church and secular civil society leaders together in Honiara. The local solidarity group, Solomon Islands in Solidarity for West Papua, suddenly went from a group with half a dozen individual members to an organization of organizations. Churches, local non-government organizations who provided essential services, artists, journalists, chiefs and the Young Women in Parliament Group — one of the members included Christina Sogavare, Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s daughter — all got involved.

When the MSG meeting started on June 17, Honiara’s two newspapers, the Solomon Island Star and the Island Sun, enthusiastically followed the story. On each day between June 17 and June 27, the day after the decision, the front pages of both papers — and often the second, third and fourth pages — were devoted to some aspect of the ULMWP’s campaign for membership; there were over 140 separate newspaper articles in the space of 20 days. For many in the Solomon Islands it was not just an issue of solidarity with their Melanesian kin. They saw their government’s position on West Papua as a litmus test on an independent foreign policy. Local activists felt that the willingness of the police and local civic authorities to allow people to freely march and protest in support of West Papua was a sign of the health of local democracy, 10 years after ethnic tensions threatened to tear the Solomon Islands apart.

It was not just the population in the Solomon Islands that was growing restless. The leaders of the Melanesian countries began to express concern too. In an article in Vanuatu’s Daily Post, Vanuatu Prime Minister Kilman referred to comments from ordinary people circulating on Facebook and declared that Port Moresby, Honiara and Port Vila could easily riot if Melanesian leaders were seen to be backing away from supporting West Papua.

The door is pushed ajar

On June 26 the decision was made. West Papua represented by the ULMWP was granted observer status and the Indonesian government represented by the five governors of the country’s easternmost provinces, associate membership. The MSG leaders tried to offer something to both West Papua and Indonesia, disappointing both. They recognized Indonesian sovereignty over West Papua, but they also rebuffed the Indonesian government’s diplomatic efforts to deny the ULMWP entry. In their 20th Communique, MSG leaders referred to the ULMWP as an organization “representing Melanesians living abroad,” presumably to reassure the Indonesian government that they respected the country’s territorial integrity. At the same time MSG leaders acknowledged West Papua as separate from Indonesia. The door has been pushed ajar to some kind of political negotiation and it won’t just be the central government in Jakarta that does all the talking. The ULMWP will have a seat at the table. The five governors of eastern Indonesia will also have a voice. And some of them, like Enembe, have shown independent thinking and a willingness to propose creative solutions.

The Indonesian government was less than pleased. For years Jakarta vigorously resisted calls for dialogue by West Papuans or any suggestion that causes of conflict were political in nature. In the words of Englebert Surabut, the head of the Lapago Council of Customary Chiefs, “The Indonesian government is allergic to dialogue.” For years Jakarta has wanted to avoid any suggestion that Jayapura, the capital of West Papua, was either equal to Jakarta, or that a discussion of independence was on the table. But when Jakarta closed down the space for dialogue they left West Papuans demanding political freedom with no domestic avenues left for talking about why they wanted freedom. So they took their concerns to the Pacific, to Melanesians with a shared identity who would thus resonate with their cause.

Internationalizing the West Papua issue like this is exactly what Jakarta was trying to prevent. Suddenly a Jakarta–West Papua dialogue that Papuan Peace Network founder Rev. Neles Tebay and others had been pushing for the better part of 10 years might look moderate. On the other hand, the elevation of the ULMWP might cause hardliners within the Indonesian government to push harder. But there is no going back. For the time being, at least, the political dynamics have gotten much more complex and unpredictable — full of possibility. Sogavare was particularly explicit, telling the Island Sun that “a forum where the two political groups can engage in dialogue” has now been created. Whatever the case, the Indonesian government will have to respond.

Relentless unarmed resistance inside West Papua and unprecedented solidarity outside the country — in West Papua’s Melanesian neighbors — has turned West Papua’s long-running struggle for freedom into a cause célèbre in the Pacific. The MSG has become West Papua’s first international forum for dialogue. West Papua and Indonesia will sit across the table from each other. Vanuatu and the FLNKS have confirmed their support. The Solomon Islands government has emerged as a stronger ally. Papua New Guinea and Fiji will have to deal with sustained and organized domestic discontent and the other Pacific Island countries are beginning to stir. On June 26, the MSG finally brought West Papua back to the Melanesian family. As Benny Wenda said, “With the region firmly behind us we will now take our message to the world.”

Haluk and Alomang have since returned to West Papua resolute in their commitment to nonviolent resistance. They and the other members of the ULMWP are now preparing for the Pacific Island Forum, a meeting of 16 Pacific Island nations that will gather in Port Moresby in September. The ULMWP have already secured West Papua as one of five priority agenda items, along with climate change. “We have to finish this,” Haluk told me. “Freedom will come.”

This article is an edited excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book “Merdeka and the Morning Star: civil resistance in West Papua.”

This is a great description of recent diplomacy fueled by grassroots action for West Papuan freedom. For those wanting to keep up with events and issues around West Papua, the East Timor and Indonesia Action Network (ETAN) with the West Papua Advocacy Team publish the monthly online West Papua Report, see http://www.etan.org/issues/wpapua/default.htm. ETAN also has a a constantly updated email listserv with news and more, see http://www.etan.org/resource/elecRsrc.htm#West_Papua_News

A marvellously readable and clear explanation of the confusing outcomes for WP from the Vanuatu MSG meeting. Also full of signs of hope for the WP/Melanesian struggle (history, heritage and identity) in relation to the greater economic and military power of their neighbours.

Jason’s story of the historic WP petition to MSG and its size shows what a wonderful example of nonviolent-assertion of rights it truly is.

West Paupua … Merdeka. Good to see the fight gaining momentum.

Waaa..waaa..waaa..waaa..waaa….

Thank you for this article. Greetings and prayers from Port Numbay-Jayapura, West Papua

Markus Haluk

we are very grateful to God the creator of heaven and earth west Papua, we are very grateful to leaders of MSG and we are also very grateful to the west Papua fighters and other supporters.

I represented the west Papua gob full support in the hope that:

Melanesia is not Indonesia and Indonesia is not Melanesia.

so we must save kenerasi successor to Melanesia (west Papua).

Thank you for your support.

Huray for the people of West Papua in their nonviolent struggle for independence and dignity, justice and peace for their people.

Peace, Prosperity and Progress for Papuans

The situation in two Indonesian provinces of Papua and Papua Barat, known in academic discussions and media reportage as West Papua, has received more and more attention from diverse quarters in the past few years. The discussions and reportage are largely related to the human rights situation in the region and the activities of West Papua-related groups such as the United Liberation Movement of West Papua (ULMWP). This includes an article written by Dr. Jason Macleod on the 25 August online edition of Waging Nonviolence entitled “A new hopeful chapter in West Papua’s 50 years freedom struggle”.

While I respect Dr. Macleod’s academic works and background, I find that many of his statements in his article need clarifying. I will offer an alternative view from my personal observations.

Like many other parts of Indonesia, West Papua has been experiencing tremendous changes in the past ten years. Through the implementation of the Special Autonomy, Papua and Papua Barat have the rights and power to fully utilize their resources for as great benefit as possible for the people in the regions. This has been coupled by additional financing for development and infrastructure from the national government. As a result, among other key achievements since 2002, poverty declined from 46 percent to 37 percent.

As part of the efforts to accelerate progress in Papua and Papua Barat, access has been provided to the people of the provinces to enter respectable institutions for higher education. Opportunities are wide open for them to pursue a career in government institutions and the National Armed Forces and Police, as well as to do businesses and entrepreneurship. All of these measures are also reinforced by affirmative policies and steps in various sectors.

Democracy in West Papua is also starting to flourish. Papuans actively participated in the 2014 legislative and presidential elections. By the end of this year, hundreds of Papuans will compete for mayoral positions in direct local elections. In comparison to other provinces in Indonesia, Papua and Papua Barat have the largest proportion of local leaders representing their electorates.

The political right and freedom of expression of West Papuans are fully assured by the Constitution and Law No. 9/1998. Therefore, Dr. Macleod’s statement in his article which says that “the rest of Indonesia may be a democracy, but in West Papua freedom of expression is prohibited” is unfounded.

It must be admitted, however, that much remains to be done for Papua and Papua Barat.

This is why President Joko Widodo has made a strong commitment to redoubling his government’s efforts in ensuring peace, prosperity and progress for West Papua. He committed himself to ensure that the political, social, cultural and economic rights of West Papuans are respected.

One of the most important steps he has taken is to be physically present among the West Papuans; to have direct dialogue with them, listen to and help realize their aspirations. This is certainly in contradiction to what Dr. Macleod refers to in his article as the Indonesian government being allergic to dialogue.

Another important step by the President was in May 2015, when he granted Presidential pardons to five West Papuans—two serving life in prison and the other serving 20 years. Upon granting the pardon, the President said, “Today, I have granted pardons to five Papuan prisoners. This is part of the government’s genuine efforts to rid the stigma of Papua as a conflict region.”

Together with the Indonesian provinces of North Maluku, Maluku and Nusa Tenggara Timur (East Nusa Tenggara), Papua and Papua Barat are home to Melanesians. With more than 300 distinct ethnic groups and more than 700 local languages and dialects, Indonesia is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world.

In Papua and Papua Barat alone, there are hundreds of unique ethnic groups. This is why the country’s motto is Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, which means unity in diversity. Contrary to Dr. Macleod’s statement that it is a lie that Indonesia had a sprawling population of Melanesians, in fact there are a substantial number of Melanesians that form an integral part of Indonesia.

With such a rainbow of ethnic diversity, integration of Indonesia to the Asian and Pacific regions is pivotal. This is why Indonesia places particular importance on its participation in fora of cooperaiton such as APEC, Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF) and Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

Indonesia always advocates that the Pacific islands countries which are not members of APEC must be given the opportunity to benefit from the APEC cooperation. Indonesia also recognizes the critical importance of sufficient resources for Pacific islands countries to respond to development challenges, including those which are caused by climate change.

In recognition of the critical importance of cooperation between Indonesia and the Pacific Islands Countries in mitigating the impact of climate change, Indonesia has allocated a modest funding of USD 20 million for capacity building programmes for the period 2015 – 2019 for the Pacific islands countries. Bearing this in mind, Dr. Macleod’s claim that the Indonesian government invested USD 20 million to derail the ULMWP’s campaign is therefore baseless. The assistance was completely intended for development cooperation.

Being an archipelagic country, Indonesia places a high priority on working more closely with the Pacific Islands Countries to conserve and enhance fisheries and marine resources, as well as to build key linkages between the countries’ marine protected areas. In line with this policy, Indonesia is a major proponent of expanding the participation of Pacific Islands Countries in the Coral Triangle Initiative. In addition, as part of sharing experiences in disaster mitigation and management, Indonesia involved Pacific Islands Countries’ participation in the disaster relief exercise in Manado within the framework of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

As a final reflection, I must underline that protecting and promoting the political, social, cultural and economic rights of the Papuans is of paramount importance. The Indonesian government and the provincial governments of Papua and Papua Barat have a strong commitment towards that objective, and are working harder and innovatively in assuring durable peace as well as sustained prosperity and progress for the Papuans.

I wish to make it clear that the above post is from a representative of the Indonesian government. Having said that I am pleased that the honorable Dr Mulyana, the Indonesian Consul-General of Indonesia for NSW, South Australia and Queensland has made time to respond to my article. Thank-you.

I hope the Indonesian government will genuinely engage with the leadership of the ULMWP.

Despite some positive policy announcements by Jokowi he has not been backed up by the central government in Jakarta. Political prisoners remain in jail. The security apparatus still acts with impunity, using torture, beatings and killing as a tool of governance. Peaceful expression of freedom of opinion is criminalized and there is no genuine freedom of press. Migrants continue to displace Indigenous Papuans land. I don’t see the progress that Dr Mulyana describes.

The root cause of the conflict in West Papua is not economic, it is political. Specifically it is the international communities willful denial of the West Papuan’s right to self-determination.

Until there is a much deeper movement towards a just and sustainable peace by Jakarta and its international political allies, West Papuans will continue to internationalize the conflict. Among other things that will include challenging the United States and Australian governments who continue to train and arm the Indonesian security forces.