During the 2020 election, the right’s use of direct action combined with litigation and political maneuvering pushed the liberal democratic system to the brink. Leading up to the election, Trump supporters were blocking streets, bridges and highways in multiple states. As the votes were being tallied, protesters attempted to push their way into a ballot counting center in Detroit to “stop the count,” while armed Trump supporters menaced poll workers in Phoenix. These were used to amplify groundless legal challenges to the election process, and culminated in the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol, which brought the U.S. within a hair’s breadth of a coup.

The liberal response to Jan. 6 has been to mobilize government inquiries, trials, and a torrent of media castigating and often mocking the insurrectionists. Pundits name the culprits as Trump, his political allies and the conspiracy theorists that his presidency welcomed to the mainstream. There is truth to all that, but the focus on Trump also conceals a right-wing turn toward direct action that didn’t start with Jan. 6 — and won’t go away with prosecutions or finger-wagging.

Just as the left’s return to direct action has been building for the past decade, a parallel development has been brewing on the right. In 2009, the year Barack Obama was inaugurated, army veteran Stuart Rhodes founded the Oath Keepers, a far-right militia movement claiming to defend the Constitution from tyranny (which in their view means a Communist and/or Muslim takeover).

That same year, conservative pundit Rick Santelli called for capitalists to form a new Tea Party (referencing the 1773 Boston Tea Party) to oppose Obama’s moderate fiscal policies. The call went viral, capitalizing on conservative discontent and latent racist fears associated with the election of the U.S.’s first Black president. Within weeks there were Tea Party chapters and protests across the country.

The merging of right-wing direct action with an increasingly fascistic Republican Party presents a dire political landscape, and Jan. 6 showed us just how quickly it could become our political regime.

It might have been funded by billionaires and magnified by right-wing media, but the Tea Party inspired and mobilized real people. There were frustrated working-class families and everyday conservatives drawn to a movement of their own, and their numbers were stacked with white supremacists exploiting racist fears of the moment, nationalist militias and “birthers” — the conspiracy theorists who believed Obama was not born on U.S. territory and therefore was an illegitimate president. Trump himself entered the political sphere by promoting the birther conspiracy. The so-called “alt-right” brought fascist ideology back into mainstream political discourse, and the stage was set.

The “Make America Great Again” movement that Trump catalyzed only expanded the trend of mobilizing, radicalizing, and intermingling fed-up conservatives with white supremacists, militia members and conspiracy theorists who claim to defend the U.S. from an impostor. Members of the Oath Keepers in particular would figure prominently in the Jan. 6 assault.

Like the Tea Party and broader MAGA movement, the Capitol insurrection was planned and organized in direct coordination with elites. The ability of politicians, capital interests and boots on the ground to further each other’s goals is one of the most dangerous aspects of right-wing direct action going back to the rise of fascist parties a century ago.

This escalates in multiple ways. For example, when fascists inflict extralegal violence, right-wing politicians move to legalize it. At the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, neo-Nazi James Alex Fields, Jr. murdered Heather Heyer and injured more than 30 others by driving his car into antifascist protesters. In the aftermath, Republican legislators in multiple states introduced laws protecting motorists from prosecution for doing the same. In the past year alone, there have been more than 100 documented incidents of drivers deliberately ramming protesters with their cars.

Right-wing and left-wing direct actions are not the same in form or content, but they both represent a departure from representational politics, which is based on indirect action (or often indirect inaction).

Other examples abound. In 2014, Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy won an armed standoff with federal troops over his refusal to pay government fees to graze his cattle, and charges against him were dismissed. The following year, two Oregon ranchers were convicted of arson for burning federal land and, in response, Bundy’s son Ammon led an armed occupation of a federal office, only surrendering after a shootout. Trump later pardoned the arsonists and Ammon Bundy is now running for governor of Idaho.

At least 57 people who played a role in the Jan. 6 insurrection are running for public office in 2022. Pro-Trump Republicans are also moving to replace elections officials around the country to solidify their control over results, using among other things violent threats by supporters to push out non-partisan officials. Trump is already talking about pardons for Capitol rioters facing charges.

These developments build on a long history of right-wing vigilantism that has included generations of state-sanctioned murder of Black, Indigenous, and brown people, and coordinated repression of movements for justice. This same legacy empowered the likes of Kyle Rittenhouse and James Fields to attack and kill left protesters in front of police.

The merging of right-wing direct action with an increasingly fascistic Republican Party presents a dire political landscape, and Jan. 6 showed us just how quickly it could become our political regime.

Direct action and democracy

Right-wing and left-wing direct actions are not the same in form or content, but they both represent a departure from representational politics, which is based on indirect action (or often indirect inaction). A liberal approach to social change encourages grievances to be processed through bureaucracies of the representative system, while a direct action (or radical) approach seeks the shortest path between needs and results.

As Voltairine de Cleyre put it in her 1912 essay, Direct Action: “Every person who ever had a plan to do anything, and went and did it, or who laid his plan before others, and won their co-operation to do it with him, without going to external authorities to please do the thing for them, was a direct actionist.”

The word “democracy” translates to “rule by the people.” Though it is popular to refer to the U.S. political system as a democracy, the “founding fathers” formed the Constitution in order to abolish the monarchy in such a way that would also prevent rule by the people. The liberal democracy that resulted from this origin — evolving over time in response to generations of pressure by movements from below — grew into a system in which citizens have individual political rights and formal equality alongside a rule of law that excludes large swaths of people, and enshrines a profit-driven economy based on private property derived from colonialism and enslavement.

This combination is inherently contradictory, and while it has been patched together by varying combinations of exceptionalism, patriotism, consumerism, and multiculturalism, its material failures inevitably lead to mounting inequality and deepening popular frustration. This in turn leads people on all sides to increasingly pursue their goals outside the bounds of the system.

As a mode of political participation, direct action runs on a different logic from liberal democracy, but it is nevertheless always present beneath the surface. The right is using this logic to kill democracy and spread authoritarianism. The left can use it to advance a more equitable, just and community-based version of democracy — if it embraces direct action in its strategies.

Direct action is a facet of politics in all places and times, but there are moments when it seems to move to the forefront. In such eras, massive change is possible, and that change can cut many ways.

Despite the contradiction in operating logics, direct action can also play a role in formal democratic politics. This has certainly been true of the far-right’s rise in the Republican Party. On the left, Bernie Sanders attempted a pair of movement-esque presidential campaigns, and since then some sectors of the left have focused on electing progressives to government posts with growing success. The main difference is the Republican Party has proved deeply vulnerable to fascist politics, while the Democratic Party continues to expend enormous energy and resources to block the advance of socialist politics from within. The failure of the Progressive Caucus to pressure the Biden administration into making good on its promises is but one recent example.

To the extent leftist representatives can achieve the kinds of tangible progress society requires, they will need leverage created by social movements to do it — and perhaps simply to protect them. After Jan. 6, progressive members of congress voiced concern about their physical safety around their own colleagues. And the Capitol insurrection should drive home the unavoidable reality that leftists, even if they’re in congress, absolutely cannot rely on the police to be the last line of defense from the radical right.

Direct action is not only combative. In fact, it is in its less-confrontational versions that alternative visions of democracy are most palpable. Among the most inspiring stories in COVID times have been widespread mutual aid efforts based on anarchist models and often organized by activists who came together in political struggle.

The same has been true during many recent moments of collective adversity. Organizing frameworks and networks established during Occupy Wall Street were able to mobilize swift and effective disaster relief and rebuilding after Hurricane Sandy devastated Far Rockaway and other parts of the New York City area. Yet, as faith in the system fades across the political spectrum, confrontational direct action to fight for and defend people’s needs will be increasingly necessary.

Organizing on the edge

The Jan. 6 insurrection came far closer to a coup than those presiding over the aftermath would like us to believe. Crowds of rightwing insurrectionaries were easily able to push their way past understaffed, ill-equipped and in some cases unresponsive police lines. At multiple points they were mere steps away from physically attacking members of congress. Democrats have referred to Jan. 6 as an attempted coup, but only to use it as a political football against Republicans. The liberal establishment seems to want a return to the representative system, partisan politics and unaccountable market economy that led us to the rise of Trump’s right in the first place. Taking seriously what a coup would mean demands a different response.

Trump whipped up the mob with his Jan. 6 speech, but had the Commander in Chief of the armed forces marched along with the crowd and entered the Capitol himself, it is entirely possible the government would have collapsed. Fortunately, Trump is a coward who spent the day watching TV and hoping someone else would make a coup for him.

Next time we can’t count on such luck. Above all, the Jan. 6 insurrection — and the traction of unfounded claims of voter fraud that preceded it — exposed the fragility of the U.S. political system. Whether they’re challenging for power at the polls or on the streets (or very possibly both), far-right forces will learn from their near miss.

The left’s direct action is not only confrontational, but also takes the form of neighborhood forums, workplace discussions, alternative economies, mutual aid and more.

Steve Bannon, right-wing strategist and CEO of Trump’s 2016 campaign, recently called for “shock troops” to take over the country and “deconstruct” the government following the next elections, and armed militias are preparing. Trump’s former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, openly suggested the U.S. needs a military coup, and retired army generals have since warned of the very real possibility in 2024. In the days following the Capitol insurrection, right-wing militia membership skyrocketed.

The exposed and deeply divided representative system is weaker now than it was during the 2020 election cycle. When challenged, that weakness is likely to manifest through repression, just as previous eras of direct action on the left were met with brutal combinations of violent force and cooptation. But it also marks an opportunity to change the balance of power both for forces of justice and our enemies.

The gravest threat comes from the far-right, as they simultaneously attack the body politic from the outside and seek to merge with the state. Electing Biden bought us time with something approximating the liberal status quo, but his administration’s missteps and letdowns are also cementing the popular understanding that partisan politics can’t or won’t help regular people. The sooner we acknowledge and reorient to this reality the better.

A new era of direct action

“Direct action gets the goods.” Popularized by the Industrial Workers of the World in the early twentieth century, and renewed by civil rights and revolutionary movements of the 1960s, this slogan marks the height of the left’s understanding of power. It is a radically simple concept — movements don’t win by asking, but by doing.

Direct action is a facet of politics in all places and times, but there are moments when it seems to move to the forefront. In such eras, massive change is possible, and that change can cut many ways.

We are on a collision course with the far-right embracing the same idea, both those with and without badges, foreshadowed by events in Charlottesville, Kenosha and Portland. That is a frightening proposition. And, as in previous eras of direct action, our moment comes with drastically heightened risk of repressive violence from the state. Regardless, up against a fracturing political system and a vicious right-wing that is more organized and emboldened to act than they have been in generations, we have little choice. We are confronted with a political landscape that will require direct action.

Between growing strikes, radical organizing and mass uprisings in recent years, the left has what it takes to meet the moment. So many workers went on strike in the fall of 2021 that the media started calling it “Striketober” and “Strikesgiving.” Many of these were successful in achieving tangible wins. Nearly half a million teachers went on strike in 2018, with more following in subsequent years. Although still in its infancy when compared with the height of U.S. labor power, the energy around recent strikes and organizing efforts marks a return to labor militancy.

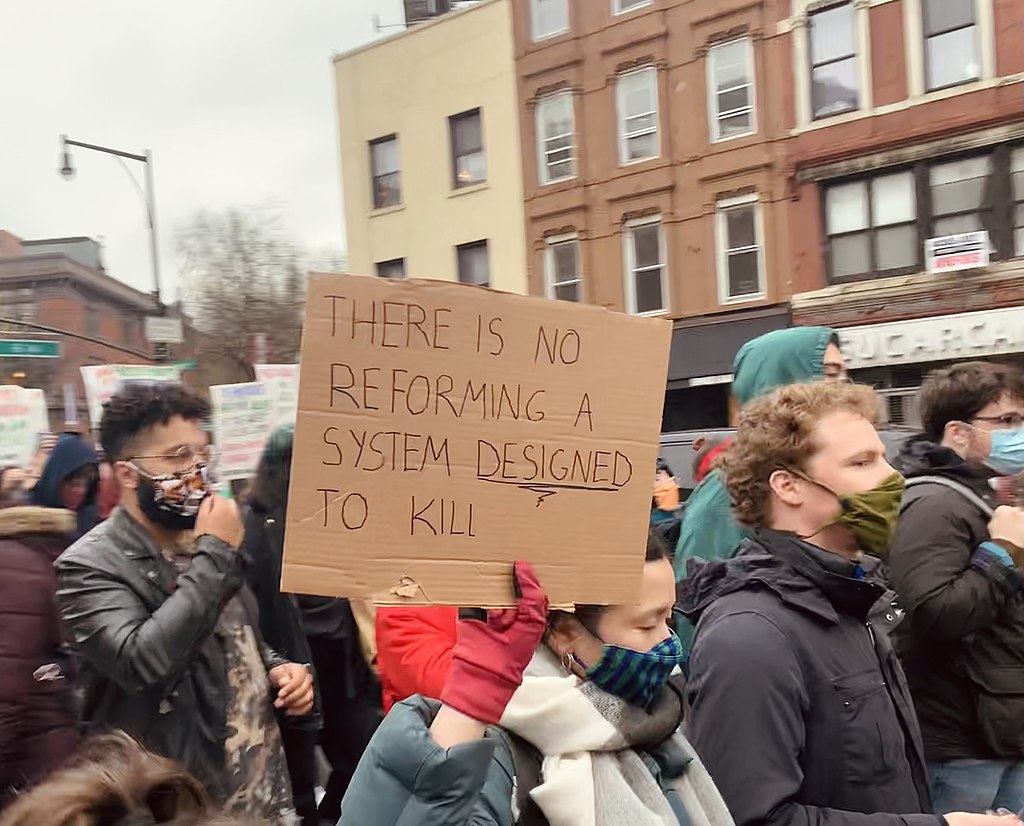

These victories come on the heels of a massive, global racial justice uprising in 2020, perhaps the largest mass movement in U.S. history. Before that, our moment stands on the shoulders of Black Lives Matter uprisings, Occupy Wall Street, the Wisconsin Capitol occupation, #MeToo, Standing Rock, #RickyRenuncia, and so many more movements that have disrupted the status quo to force change.

The left’s direct action is not only confrontational, but also takes the form of neighborhood forums, workplace discussions, alternative economies, mutual aid and more. From housing rights and community defense to medical care and abortion access, our needs may increasingly need to be met by organizing around the principle of doing, not asking.

Larger scale shifts around systems like policing, poverty and climate destruction will require the leverage of direct action to stand a chance. It may not always get the goods, but the more we take action together to get what we need as directly as possible, the more confidence we build as agents of our own future.

The turn toward direct action is changing the terrain. It will expand possibilities for people to self-organize, it will ramp up pressure on the state to crush or incorporate these attempts, and it will provide allies within the state with leverage — politicians will no longer rely exclusively on votes, or on the use of state forces, but also on committed supporters willing to take action into their own hands.

Militant labor is already teasing the possibility of unshackling itself from the restrictions of labor relations law that was created to undercut workers’ power. And recent uprisings mean that millions of people, particularly young people, have gained experience in taking the streets.

We cannot win a livable world by shying from the moment. In the midst of massive disruptions and disjunctures of COVID and worsening climate shifts, it is incumbent upon organizers to think outside the box. Our moment presents opportunities to expand rank-and-file labor militancy and connect it with social justice and climate action in new ways, and to push for the policies we need through radical mixes of democratic local governance and collective action.

We face a political field in which our wins will increasingly have to be fought for, built, and defended using direct action tactics — from community organizing, mutual aid and institution-building to strikes, barricades and other forms of disruption.

The left cannot afford to be the last ones trying to play by the rules. We are living in a time of urgency, and the coming age of direct action may well prove decisive for our future.

Thank you Ben Case for the overview of current right wing organizing. I would argue, though, that the right has always used mob violence, which is also direct action. In the 1960s they used every tool: politics (Wallace), civic (White Citizens Councils) and terror (Klan). Also it’s important to recall that they built “alternative institutions” (segregation academies), mounted boycotts (the so-called “Massive Resistance”), and staged marches (many, many patriotic parades). They have also “stood witness” and blockaded abortion clinics for decades. They even developed a new nonviolent tactic: the ‘baby crawl’ where they moved toward their target with minimal physical confrontation.

They have organized under many names–Silent Majority, Christian Right, Right to Life, Tea Party– but they represent the same hate and fear.

I think we are moving ahead and growing, with strikes, Occupy, BLM, Sunrise, water defenders, the new poor peoples campaign, and more. We don’t have the institutional power, but we have the numbers.