On Tuesday the trial of former Guatemalan dictator Efrain Rios Montt opened in Guatemala City. Facing charges of genocide and crimes against humanity, Montt is the first ex-head of state to face allegations of this kind in a national court. He ruled during a particularly bloody phase of the conflict in the early 1980s, when tens of thousands of people were killed by the state. Montt has been charged with ordering the killing of more than 1,700 indigenous people of Mayan descent. The tempestuous first day in court — with fiery statements from both the prosecutor and the defense — was broadcast live across the nation.

After the 1996 peace accords, a United Nations-backed truth commission — The Commission for Historical Clarification — found that the army and paramilitaries were responsible for 93 percent of the documented violations. Though the focus of the commission was on fact-finding and not restorative justice, Nobel peace laureate Rigoberta Menchú Tum used the commission’s final report to file a case against Montt and others for their involvement in the atrocities. In January 2012 a Guatemalan court charged the former strongman with war crimes.

“Until quite recently, no one believed a trial like this could possibly take place in Guatemala, and the fact that it is happening there… should give encouragement to victims of human rights violations all over the world,” United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said in a statement. Quite likely, without the work of Guatemala’s truth commission, this trial would not be taking place.

Beginning with Uganda in 1974, nearly 30 truth commissions have been established in nations around the world. In some cases, like Guatemala, they have primarily been investigative. In others, they have sought to encourage restorative justice. While no one would claim that truth commissions have satisfactorily resolved the many fraught and painful dilemmas flowing from situations of intractable mass political violence, this relatively new experiment has begun to open up options to the traditional alternatives of amnesia on the one hand and vengeance on the other.

Four typical characteristics of truth commissions (identified in Priscilla B. Hayner’s study Unspeakable Truths and summarized here) are that they focus on the past; they investigate a pattern of abuse; they are temporary, and generally issue a report when they finish their work; and they are officially sanctioned, authorized or empowered by the state. This offers greater access to information but also, more importantly, it is an acknowledgment by the state of past wrongs and a commitment to address the issues that are raised.

Today marks the 10th anniversary of the release of the final South Africa Truth and Reconciliation Commission report. While commission eventually came to be regarded as a key element of the country’s transition from apartheid to democracy, Graeme Simpson of the South African Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation says that it was “almost an afterthought” — a last-minute compromise between the African National Congress that wanted “justice” and the former apartheid government that wanted “amnesty.” Following the 1994 elections that swept the ANC into power, the new minister of justice, Dullah Omar, tried to square this circle in a way that would try to avoid favoring the perpetrators.

As one account summarizes this novel approach, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission “dealt with gross crimes against humanity and focused on the period between the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and 1994. Perpetrators had the opportunity to apply for amnesty for crimes committed during that period. The TRC would award amnesty if the individual could demonstrate a political objective and if they told the complete truth. The South African TRC was unique because of this amnesty in exchange for truth formula.”

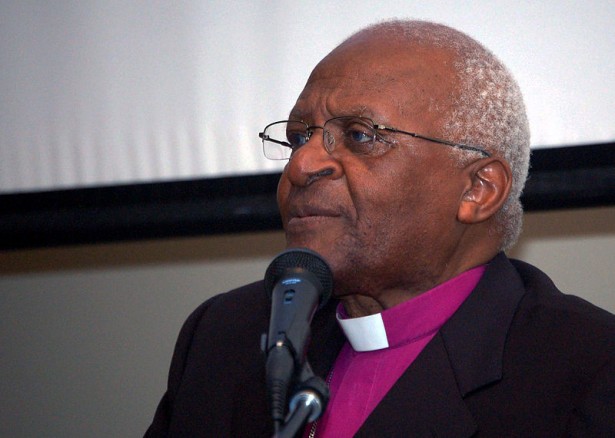

In keeping with the spirit of disclosure, the commission meetings — co-chaired by longtime anti-apartheid campaigner and Nobel laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu — were open to the public and were widely covered by the media. The commission heard testimony of over 21,000 survivors of violence, with 2,000 giving testimony at public hearings.

Video reports featuring Truth and Reconciliation Commission testimony were broadcast weekly in South Africa from 1996 to 1998. Ninety-one of these broadcasts are posted here. They are harrowing television — the painful accounts of assassinations, disappearances, torture and jail, often told by surviving relatives.

The painful question that hangs in the air after most of the depositions is: Where is justice for my loved one? Even as the post-apartheid regime tried to navigate a new way forward by balancing truth-telling and accountability, that unquenchable question remained. (In the end, amnesty required meeting a series of criteria. Far more applications for amnesty, on both sides of the conflict, were turned down than were granted, as this summary from the Cornell University Law School documents.)

One of the outstanding issues that continues to confront South Africa was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendation of government reparations to victims of violence. While some reparations have been made, in general this has been lagging, which has been an increasingly pointed issue in civil society. (Even as the reparation fund grows, disbursement has slowed.)

The issue of evaluating the long-term impact and effectiveness of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in promoting restorative justice, healing and peacebuilding is still being worked out. Nonetheless, this 40-year experiment with truth and reconciliation casts a new light of hope and possibility for breaking cycles of retaliatory violence culturally as well as individually. All of us have much to learn and build on from this growing lineage of nonviolent change.

It is a quirk of history — or is it? — that the South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report was issued the week that the United States invaded Iraq a decade ago. One accounting of mass violence was emerging at the very moment that another spasm of systemic violence and injustice was being unleashed. The simultaneity of this reinforces the need for a truthful account of U.S. policy — one that would place at its center the voice of those whose lives were destroyed and disrupted.

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the U.S. Iraq War could go a long way to laying bare the reality, roots and consequences of this war. If there is ever to be healing, let alone real peace and reconciliation, the truth must be spoken and justice must be built.