West Virginia teachers, who stunned the nation with their historic 2018 strike, staged a two-day walkout in February and are continuing to battle their Republican-dominated state government this summer. While the immediate issues this time are legislators’ attempts to introduce charter schools and impose stiffer penalties on strikers, the need for greater public funding of education remains the core of the struggle.

In the new book “Red State Revolt,” author Eric Blanc describes the origins of this strike and the wave of subsequent strikes it ignited across the country by giving a play-by-play account of the action — offering lessons that apply to future strikes, as well as other kinds of nonviolent action.

Blanc was well placed to observe the strikes. Sent to cover them by Jacobin magazine, his approach could be described as a participant observer — in that he not only wrote about the strikes, but also helped organize national solidarity actions. As a former high school teacher himself, he became a trusted confidant, interviewing service personnel, students, union staffers, and various officials to get their take.

Despite admitting to an “unabashedly partisan account,” Blanc insists that he “tried to remain scrupulously committed to the facts” and expects that no one will fully agree with his conclusions. Overall, it is clear from his approach that Blanc is more interested in showing the effectiveness of certain strategies and tactics — as well as explaining the relevance of the strikes to broader political issues — than in promoting the account of any individual or group.

The backdrop

West Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona were unlikely candidates for state-wide strikes in 2018. All three are so-called right-to-work states, meaning that non-union workers do not pay fees to unions for representing them in collective bargaining. What’s more, all three states are dominated by conservative Republican legislators and governors, which support laws that make it illegal — as it is in most states — for teachers to go on strike. Given this environment, teachers’ unions have long been cautious, when it comes to bargaining for pay, benefits and improved working conditions.

Previous Coverage

Labor organizer Jane McAlevey on why strikes are the only way out of our current crisis

Labor organizer Jane McAlevey on why strikes are the only way out of our current crisisThis non-militant, “service” model of unions emerged as a result of deindustrialization, the immensely damaging outcome of the air traffic controllers strike of the early 1980s, and the closer association of unions with reformist advocacy groups, as well as the centrist Democratic party.

Nationwide, long-term declines in education budgets have also led to lower teacher salaries — relative to the cost of living — plus increased class sizes, outdated textbooks and an overall greater difficulty in delivering the quality education they seek for their students. For example, one in five teachers has a second job and many are forced to purchase instructional materials for their classrooms.

Enter the militant minority

After years of relative passivity and accumulating grievances, it took a militant group of teachers in West Virginia with a “class struggle orientation” to organize their colleagues and prepare to strike. These teachers traced their activism back to the Bernie Sanders primary campaign of 2016, which spurred the founding of several Democratic Socialists of America chapters. Teachers from some of these chapters started to think seriously about taking collective action after forming a study group during the summer of 2017 to teach themselves about labor activism.

When the new school year started, these teachers were ready to organize their colleagues around the state. Helping matters along was the state’s announcement that dues would be increased for the public employees’ health insurance plan and that teachers would be required to wear invasive body monitoring devices. The militants created a Facebook page to widen discussions among teachers and other public sector workers. From there, momentum built steadily, as the teachers organized and engaged in actions of increasing size and risk in order to build greater support. When the time for the strike came, 80 percent of the state’s teachers voted to walk out.

The pivotal moment in the West Virginia strike occurred about halfway through the nine-day labor stoppage, when the official teachers’ unions announced an agreement with the state legislature and governor. In short, because it had failed to solve the health insurance funding issue and they were not asked to vote on it, the teachers decided to publicly oppose the agreement and continue the strike. Gathering at the capitol in Charlestown, they chanted “Fix it now,” “Back to the table” and “We are the union bosses,” asserting their voice over that of the three established unions.

Previous Coverage

How free lunch and daycare are bolstering the Oklahoma teachers’ walkout

How free lunch and daycare are bolstering the Oklahoma teachers’ walkoutSpurred by the success in West Virginia, militant teachers in Oklahoma and Arizona were able to spark major actions in a matter of weeks. In Oklahoma, there was huge energy, with massive strikes taking place at the state capitol for days on end. However, there was relatively little teacher-to-teacher organizing within the schools. Instead, self-appointed leaders managing a teachers’ Facebook page were at the center of much of the communication, and there was little democratic decision-making.

In the end, despite winning average pay increases of $6,000 per teacher and modest new funding for education, the Oklahoma teachers strike dissolved after the union called on teachers to go back to work. The problem, according to Blanc, was that Oklahoma’s teachers were “insufficiently organized to overcome the hesitancy of their union leaders” in contrast to West Virginia, where the teachers went “wildcat,” taking it upon themselves to continue the strike without the union’s blessing.

The Arizona case was similar to that of West Virginia. A militant group of teachers understood the importance of face-to-face organizing and had liaisons in nearly every school. For Blanc, one of the most impressive aspects of the Arizona strike was that it occurred in the most difficult environment: a very conservative, anti-union state with a government beholden to the Charles Koch Institute and American Legislative Exchange Council.

As in the other two states, Arizona militants set up a Facebook page that quickly became very popular. But, in contrast to Oklahoma, key organizers in Arizona recognized that it was critical to build from the base and made sure they had enough organizational strength to call for a strike. They also established a consultative process that encouraged input from below in decision making through what was called a “site liaison network.”

What the strikes won

In all three states, teachers won significant pay increases — some immediate, others to kick in later. They also won increased funding for schools and students, although those increases were small compared to the budget cuts of the past decade. A big issue in all states, still largely unresolved, is how to pay for the increased education funding.

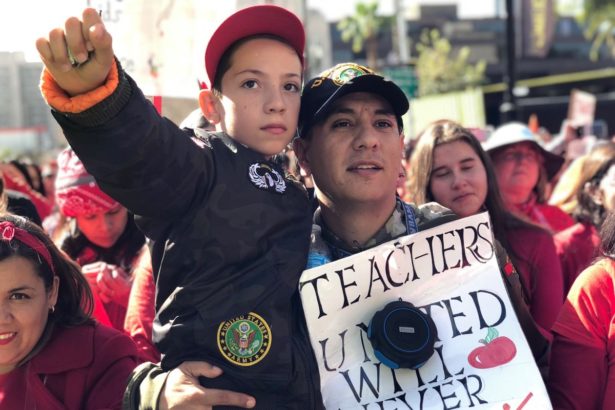

Beyond the specific gains by teachers and schools, however, the strikes established a foundation for further union building. Blanc quotes teachers who talked about how their participation in the intense struggle gave them a new sense of personal efficacy and collective power. As one Arizona teacher noted, “Rallying at the capitol was one of the few moments in my lifetime where I felt I stood exactly where one ought to — it was unequivocally purposeful, courageous and joyful.”

Blanc’s overall assessment of the strikes is multi-layered. Although the immediate gains for teachers, other public sector workers, and people living in those three states were meaningful, they were by no means transformative because they did not disrupt overall power relations. While further struggles are needed to defend and entrench their gains, he argues the teachers’ movements — on a broader level — amounted to a “frontal challenge to austerity and neoliberalism.” Blanc thinks they also appear to clearly portend “a dramatic increase in working-class consciousness and organization, setting the stage for the conquest of further victories in the months and years ahead.”

Lessons learned

The red state revolts took place in settings different from standard labor action, where workers join unions and then engage in struggle through those unions. In the 2018 cases, unions were constrained because they could not legally call for strikes. In addition — like many unions these days — they were focused on member services, rather than fights with the bosses. That meant it was largely up to the teachers to do the hard work of organizing their colleagues and preparing for strikes. The unions did provide important logistical and financial support, which teachers recognized as crucial to their ultimate success. But the strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona, were ultimately led by the teachers themselves. Teachers in other states — including Kentucky, North Carolina and Virginia — also took it upon themselves to mount one-day walkouts.

Not being able to organize within a formal union structure was a definite challenge, seen most clearly in Oklahoma, where the lack of grassroots organizing amounted to a significant weakness that ultimately led to the strike’s collapse. In contrast, in the 2012 Chicago strike and the Los Angeles strike of early 2019, all organizing was done within the union framework and benefited from union largesse, as well as an experienced, militant leadership. These more typical cases took years to develop, whereas the red state revolts built within a matter of weeks.

Another notable difference between these two types of teacher strikes, was the role of social media in the red state revolts. Despite his initial skepticism about Facebook, Blanc ultimately concluded that without it the teachers would not have been able to organize so quickly. That being said, Facebook organizing was something of a shortcut, particularly in Oklahoma, where teachers saw what happened in West Virginia and believed that they could do the same thing using Facebook and word of mouth.

In the end, they did indeed prove that advanced communications tools, along with very strong grievances, were enough to pull off a massive strike that actually sustained itself for several days. But that structure was built on a weak foundation that ultimately led to dissolution. The general lesson for organizers should be that social media provides excellent tools for dialogue and communications, but cannot replace the hard organizing work and democratic decision-making infrastructure necessary for a lasting social movement.

It is also significant that teachers are particularly well-placed to engage in strikes. Although they cannot disrupt the economy directly the way industrial workers can, they are still able to upend daily life. Students need to go to school, where low-income kids are fed one or two meals a day, and parents need to go to their full-time jobs. To use the leverage of disruption effectively, teachers have realized that they must stay on the side of their students and their communities.

Everywhere teachers strike, they clearly articulate the objective of helping students achieve their educational goals. They also work assiduously to deliver food to students and organize temporary daycare centers in order to minimize the disruption to low-income families. In all three states, there was overwhelming support from the community, which understood all too well the deteriorating state of their schools and implicitly trusted the teachers from day one.

This support insulated the teachers from government repression. Although state officials threatened teachers before the strikes, there was little they could do when such overwhelming numbers walked out. Blanc quotes various officials saying they knew that if they were to arrest teachers or coerce them with threats of fines, they would face a huge backlash that would only strengthen the teachers’ political standing and resolve. For their part, the teachers understood early on that if they walked out in large numbers, there was nothing the authorities could do.

The strikes can also be seen as confirming key elements of nonviolent direct action. Teachers in West Virginia and Arizona carefully studied their strengths and weaknesses relative to their opponents in the state governments. That understanding was used to build their movements deliberately, ensuring accountability and important aspects of democratic decision making. The teachers recognized and empowered their allies — their kids and their kids’ families — and were adept at communicating their goals to society in general.

Finally, the teachers realized the importance of building solid structures from the ground up. Yet, events moved so quickly that there were limits to how far those communications channels and self-help networks could be institutionalized.

While “Red State Revolt” was about the teacher strikes of 2018, it tells the story of what, in essence, were progressive social movements resisting the politics of austerity imposed by hard-line conservative forces. For activists seeking to build progressive power, whether through labor activism or by organizing racial and economic justice coalitions, “Red State Revolt” is full of helpful practical and theoretical insights.