It was several years ago that the Curator of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection was contacted by Colonel Ann Wright. She was inquiring about whether the Peace Collection would be interested in being the repository for her papers that documented herself from 2003 through 2020. After hearing Wright’s story of her life’s trajectory, which changed dramatically because of war, the answer was a

resounding, “YES.”

Wright wrote “…My family will thank you forever as they think my saving all these materials is pretty crazy!!”

Former Curator Wendy Chmielewski replied, “Thank goodness for all those ‘crazy’ people who have saved their papers and files! These are the records of human history. As a historian myself, I am daily thankful for documentary evidence saved from the past, and often frustrated that my questions can’t [all] be answered because no one did save items.”

Though there were already files at the Peace Collection from veteran groups and military families, this was the first extensive collection of papers from an individual who moved from a military and diplomatic career to being a vocal peace activist.

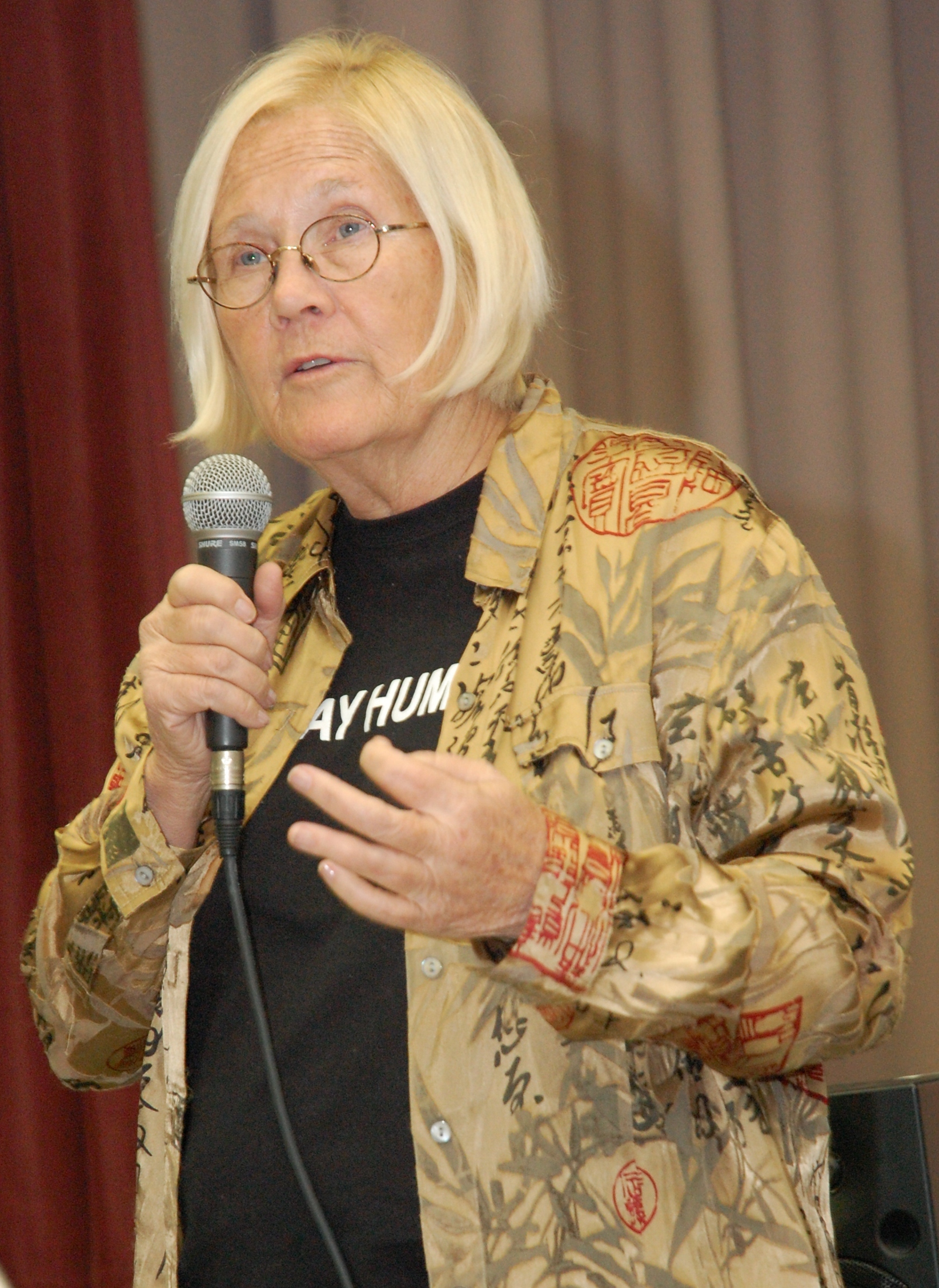

As the Peace Collection’s Archivist, it was my privilege to sort through Wright’s 30+ cartons of papers. They were full of fascinating stories and details about her resignation as a diplomat (she had served in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Grenada, Micronesia, Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, and Afghanistan), about her involvement with peace groups, about her many, many speaking engagements around the world,

and more. She also donated dozens of photographs, and hundreds of peace-related DVDs, buttons, bumper stickers and T-shirts.

Born in 1946, Wright graduated from the University of Arkansas in 1968. After college she joined the U.S. Army and served for three years on active duty. She then backpacked around the world and worked in Greece for the U.S. Navy. Wright received a Master’s Degree in Educational Administration and a Law Degree, both from the University of Arkansas, and also earned a Master’s Degree in National Security Affairs from the U.S. Naval War College.

Wright rejoined the U.S. Army in 1982 and served in special operations units in Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, where she became airborne qualified. She also served in Panama and countries of Central America. In 1987 she joined the Foreign Service and became a diplomat, but she remained in the U.S. Army Reserves. During her 28 years with the military, she specialized in civil reconstruction following military action, political-military affairs, and civic action and psychological operations.

Wright resigned her position as a diplomat when the U.S. declared war on Iraq in 2003. As she later related: “I did not want to be part of the U.S. Government when it went to war for the reasons the Administration was stating [such as there being weapons of mass destruction in Iraq] and that I thought to be wrong.” “I strongly believe that …. it is your professional and patriotic obligation to make your thoughts known when you see your government going down the wrong path on something with such serious consequences as going to war.” This theme of being an alternative voice became the narrative for Wright’s life over the next decade and beyond, and of her 2008 book Dissent: Voices of Conscience.

Wright knew some of the best-known peace leaders of the early 21st century. She often joined Cindy Sheehan (whose son was killed in the Iraq War) in protests against war and militarism, including at Camp Casey — set up outside President George W. Bush’s ranch in Texas. Medea Benjamin, and other women of Code Pink, were frequent cohorts of Wright on delegations overseas and for actions and

marches in the U.S., where they made themselves heard in Congressional hearings and elsewhere.

Wright became an expert on the effects of military bases in Japan and the United States, especially where violence had been perpetrated against women, including female soldiers. She wrote articles and spoke about it for years, and compiled lists of women killed by others or whose deaths were reported to be suicides but may have been murders instead.

Wright took part in actions regarding Gaza, North and South Korea, treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, drones used for killing, and other concerns. She was arrested for civil disobedience more than once in solidarity with others who were passionately protesting war and its consequences around the world. She became known by many as a voice that told the truth, no matter the consequences. She was invited to speak, to be interviewed, and to write articles that educated audiences globally.

Wright’s papers are now organized and available for research. Wright currently lives in Honolulu, Hawaii, where she is active in international organizations focused on Asia and the Pacific.