Subscribe to “Nonviolence Radio” on Apple Podcasts, Android, Spotify or via RSS.

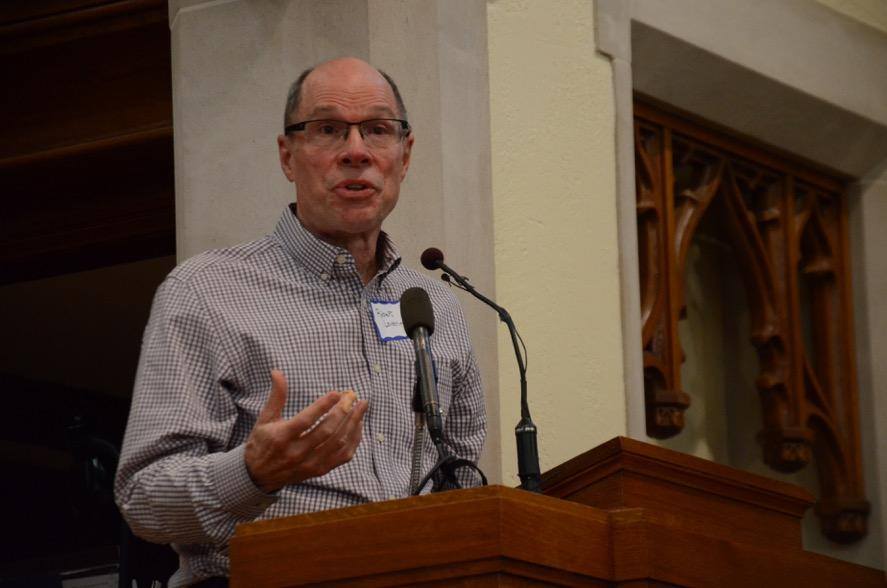

Robert Levering comes to Nonviolence Radio this week to talk to Stephanie Van Hook and Michael Nagler about the film “The Boys Who Said No!” and the powerful draft resistance movement that helped end the Vietnam War. Robert is an executive producer of the film, a position he is well suited to as he himself was a draft resister in the 1960s. In the interview, we hear how Robert worked collectively to refuse the draft, and more, to stand up actively and nonviolently to an unjust and oppressive system:

…the draft sort of makes it us vs. the government. It’s very frightening just individually to face the government and all the power it has. But the communities that we developed helped to give us the kind of strength that we really needed in order to do that confrontation.

I know that I never would have – I don’t know what I would have done. I mean, you never can tell. But it made it really much, much easier to do something as part of a community rather than just simply doing it individually.

Robert’s discussion of his work in the ’60s reveals how groups like those opposing the war in Vietnam came together with the civil rights movement to create a power that finally overwhelmed the U.S. government, pushing it to end the war and change some of its racist policies. We are seeing strong echoes of this kind of collaboration today, as shown in Michael’s nonviolence report at the end of the show: Diverse groups dedicated to nonviolence in many different forms, directed at many causes are coming together, joining hands and actively building a better world.

—

Stephanie: I’m Stephanie Van Hook with another episode of Nonviolence Radio. I’m here in the studio with my co-host and news anchor, Michael Nagler.

We’ll be talking with Robert Levering who is Executive Producer of the “Boys Who Said No!” a film about draft resistance and nonviolence helping to end the Vietnam War. It’s a very important story and one that has a lot of implications for nonviolence today. We’re very excited to have Robert Levering with us.

Robert, thanks so much for joining us today.

Robert: Glad to be here.

Draft resistance was the — you know, people who took the position that they weren’t going to cooperate with the selective service system. We haven’t had the draft in terms of drafting people into the military since 1975.

But during the Vietnam War, all young men were subjected to being drafted into the military. And the different positions you could take, is of course, you could straight in, and then you could also try to figure out some way of getting out. The way the system operated at the time, many people get deferments. The other thing is that you could apply to be recognized as an opponent of all wars, and that was called, “Conscientious objection.” Or you could try to figure out various ways of avoiding the draft.

“Draft resistance” were the people who refused to cooperate with the system. Oftentimes, because they thought the whole idea of cooperating with the system would put you into – you know, put you over in the jungles of Vietnam to be ready and willing to kill people or be killed, and this was immoral. Or you just oppose war for some other reason.

But at any rate, there was a subset of the people who were opposed to the war who refused to cooperate, and we were called, “Draft resisters.” We literally resisted the draft. Or in Gandhian terms or nonviolent terms, we were the people who were not cooperating with the system. We withdrew our cooperation with the system.

Stephanie: Robert, thank you so much. This film, I had the opportunity to screen it before our interview and wow, I was really just blown away at the way Ehrlich – Judith Ehrlich is the director. She was nominated for an Oscar for this work. She’s done other films. One on Dan Ellsberg, “The Most Dangerous Man in America.” The film is just beautiful. It just takes you through this one aspect of Vietnam – of the Vietnam era — which was the draft resistance and how it started small and how it grew, and then people’s experiences who went to prison. There are so many incredible, incredible stories in there.

So, I’d like to hear a little bit about your experience, Robert. Where were you? What did you do? And just how that fits into the whole film because it’s the stories of people that just really blow you away with how it’s a part of an orchestrated nonviolent resistance movement.

Robert: Well, I was lucky enough to graduate from college in 1966 which put me right in the middle of the great escalation of the war in Vietnam. I was someone that the system would have loved to take in. So, I had to decide, as did all of my peers, what we were going to do. In my case, I spent about a year trying to figure out – and I actually did several things to avoid going into the military. One was I went to theological school, which gave me an automatic deferment.

And then I also applied to be a conscientious objector. I don’t know, it’s a long story short, but I decided that all of those kind of alternatives, were not right for me because I just – especially – the thing that tipped me over was Martin Luther King’s assassination – that had a big impact on me. And then I just decided I couldn’t participate in the system any longer.

So, at the time of the draft system, you were supposed to carry what was called, “A draft card,” which showed that you had registered for the draft and a card that showed what your classification was — you know, whether you had a deferment or what exactly your classification was.

And so, what I decided to do was, I decided to turn in my draft card. It was at a Quaker meeting house in Philadelphia, along with about a half dozen other young men who I think were also similarly moved by Martin Luther King’s assassination. And so we decided to turn in our cards which meant that we put them in an envelope, in a service where we all spoke and said why we weren’t going to participate in the war. And then they were sent to the government to tell them that we weren’t going to go in. Okay, that was one method.

Another thing, perhaps people have seen, the thing about burning draft cards. That was another way of saying the same message. Because you were required to keep that draft card on you at all times. Anyway, that was my decision.

Now, in my case, which was very similar to a lot of other cases, the government got a little too anxious in my case and ordered me to go to induction without going through their procedures. Therefore, they made some mistakes in my case. However, in other cases where they didn’t make mistakes, many of them did go to prison. The person that I mentioned, the producer of the film, the main producer, the guy who was the inspiration, Christopher Jones, he did wind up going to prison. And went to prison for about a year or two years for refusing the draft.

Now, the people that did take that public stand, we were the ones that were called, “Draft resisters.” Christopher is a friend of mine and a friend of many, many people, and he had the idea of doing a film about the draft resistance movement. The idea that Christopher had – I guess it was seven or eight years ago – was to have a reunion of people who were draft resisters. So, as one of his friends and, other people that he knew, we had a gathering up in Marin County in David Harris’ house.

David was a very well-known draft resister. At the time of the Vietnam War, he was married to Joan Baez. Anyway, there were about 75 people which included very significant others as well as the draft resisters and we went to David’s house where we had a reunion. But during the reunion, Christopher invited Judith to come and to film a number of us, to tell our stories, our draft resistance stories.

Well, anyway, after the reunion, Judith and Christopher started, “Well, why don’t we make this into a full film?” And so, that’s how the film started. The film is basically stories of – I think there were a total of 30 different draft resisters who were interviewed for the film, and I think the final version has about 8 or 10 of the draft resisters included in the actual film. And then, of course, there’s documentary footage and a lot of commentary.

The film really focuses on what was the kind of – let’s say the conscience, why people believed that they would not participate in war, why they were going to take the stand that could land them in jail.

Stephanie: Now there are images of the war being played on television screens every night, from what I understand from the film. Can you speak to how that influenced the opinion about the Vietnam War, both for good and for perpetuating it?

Robert: I don’t know that anybody who was not a sociopath would have found the nightly news to be something that they would want to participate in. But I guess there are some people that did that. Mostly it was a horror show. At the time, one of the main tactics that the government had was to increase the number – the body count — the number of people that the Vietnamese that killed.

I think that it made a lot of us just really realize what the reality of the war really was about. And so, that just had a very big impact on everybody. I’m not sure how many people were convinced that the war was a good thing, but I think it was mostly a bad thing.

And just as a kind of footnote, since the Vietnam War, the government has done a very good job of avoiding having those kinds of scenes conveyed to the American public.

I mean what happened with Iraq and Afghanistan has been what they call – they have “embedded journalists” which means that the journalists are much more controlled than they were in Vietnam. In Vietnam, they basically had the run of the country and there was no real censorship as there had been in previous wars and in subsequent wars. So that was certainly part of the deal.

Now, one of the things that I think is really important when we talk about nonviolence was the impact that the draft resistance movement had. The draft resistance movement, just on its own, forced the end of the draft. Although, as I said, some of the people went to prison and there were others who for one reason or another were draft resisters and did not go to prison. We all thought we were. I mean, when you took that stand and you told the government you weren’t going to participate in the war, they could immediately – like in my case, they ordered me to induction, but I refused to do the induction. But they made a mistake in my case.

Well, it turns out that there were over 200,000 – 220,000 actually – who were draft resisters, who actually told the government. And that’s a huge number, okay? But of that number, only a 10th of them actually got indicted. In other words, the government – it just overwhelmed them. And so, of the 20,000 which would have been people like me, only 8000 were convicted and only 4000 went to prison.

The reason was that they were overwhelmed. They literally were overwhelmed with this resistance movement. And that was one of the main factors that the government decided they just couldn’t continue the draft any longer. I mean, it’s more complicated than that, but that was a major factor. And it was one of the most successful nonviolent movements this country has ever seen. I’m just talking about the draft resistance movement, and that was, of course, part of the overall anti-war movement which helped end the war as well.

Stephanie: I just thought the film did that so well, just picking this one issue of draft resistance and telling that story so well. You can’t leave the film without a better understanding of a successful nonviolent movement taking place in this country. So, it’s incredible to be able to talk to you about your experiences, and also to hear how wonderful that Ehrlich was able to get the interviews that she did for the film.

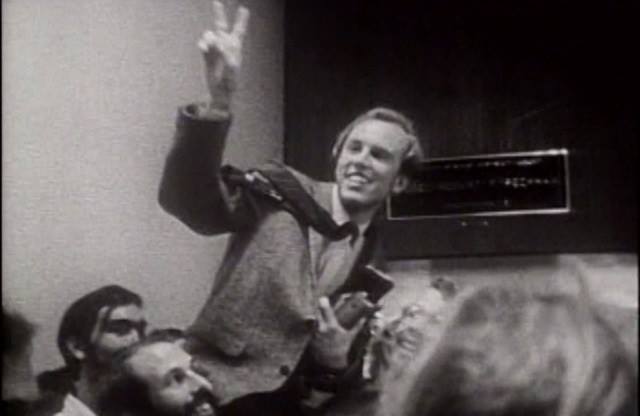

It showed the community that was being built around the resistance as well that I found very, very moving; where people going into the induction centers and the resistance folks standing on the outside saying, “You have a choice here. You don’t have to do this. There are alternatives.” You know, handing out flowers and pamphlets and so forth. And these guys going in.

And then just so moving to see, you know, one by one someone comes out because they’re like, “I can’t do this.” And when they came out, they’re cheering for them. Everybody is cheering and counseling them and giving them resources and support. And just the solidarity and support and just love. That like, yeah, come out of this death trap into life, which was so beautiful. And I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about that kind of community support aspect.

Robert: Well, that was part of – I think in the film, David Harris at one point says that the actual situation was we didn’t know how our individual – the draft sort of makes it us vs. the government. It’s very frightening just individually to face the government and all the power it has. But the communities that we developed helped to give us the kind of strength that we really needed in order to do that confrontation.

I know that I never would have – I don’t know what I would have done. I mean, you never can tell. But it made it really much, much easier to do something as part of a community rather than just simply doing it individually.

There’s one other strand that is in the film that I think is an extremely important thing to understand, and that is the influence of the civil rights movement. Younger people may not realize that there’s kind of an overlap of the civil rights movement. The height of it was in 1965 which happened to be the year that the war really escalated in Vietnam. Many of the people who were involved in the civil rights movement were, you know, they got their inspiration to become part of the draft resistance movement. The whole concept of nonviolence had such an impact.

I think that that’s this aspect that we explained in the film. And actually, the first group to – I mean an actual group of people who were draft resisters was SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. That they took a position, very strongly, to refuse induction into the draft. We interviewed one of the leaders of SNCC who did wind up going to prison as a result of his stance, just to show that overlap, that the nonviolent philosophy of the civil rights movement was very much part of what was the core of the people who were draft resisters.

The film actually goes into some detail about the group of people in Palo Alto who were around David Harris and Joan Baez and a number of others. Christopher was part of that community. It was called, “The Institute for the Study of Nonviolence,” and it was really out of that community that – particularly the West Coast part of the draft resistance movement was sort of centered around.

The film was originally about that community, but over the years that we’ve worked on it, there were five of us draft resisters who helped Christopher and Judith. We were like the advisors and sort of co-producers of the film, where we helped find the people to interview and guide. We looked at earlier versions of it and gave advice and counseled about how to improve the film.

But anyway, that was the whole point of showing the impact of the philosophy of nonviolence was really very central to many, many of the draft resisters. And many of us have been life-long participants in various causes, social movement causes, as a result of that grounding that we got in the draft resistance movement.

Stephanie: I think that’s wonderfully brought out too when women are arrested. Joan Baez is arrested with other activist women when they were blocking the induction center in Oakland. And they’re in prison and all of a sudden they realize, you know, most of the women in prison are women of color, like 93 percent of the women in prison with them were women of color.

And when they started talking and bonding with one another in there, they found that they were able to bond over the war, like that their husbands or boyfriends were over in Vietnam. And so, it really helped to also bring that piece out.

Michael: You know, there were various ways that a person could go when confronted with the draft if he did not want to go in; you could not want to go in for various reasons, some being cowardice, ranging all the way over to the kind of principled objection to war itself which you represent so well.

There was the religious objection. I have a brother in Canada for that reason. There was a famous expression when I was living in Greenwich Village at that time, “Soap in the armpits,” because you could go in for a medical and flunk your medical in various ways – the psychological part or the physical part. But none of those have a political impact. And it’s for the future to really change the system, to really wake people up.

So, the kinds of things that you did and that I was not able to do because I had this 2S and had a daughter, were the ones that really only had – the only kind that had an impact. But there’s an ambiguity here, Robert, and I’d really like to hear your commentary on it. And that is this: without the draft, what you have, in effect, is a poverty draft. In other words, people who are not well-enfranchised in the society. They’re offered an education, salary, and a social standing in some quarters by enlisting. So, the impact falls most heavily on disadvantaged communities whereas the draft, per se, is more democratic. So, could I get your thoughts on that?

Robert: I think that the draft – the draft is unnecessary. The number of people that are actually used by the military is just much, much less than they could possibly use with a full-blown draft of – so, that’s just one piece of it. Just the numbers, you know, therefore who goes in, and who doesn’t is, you know, how do they figure out? And what they did during the Vietnam War was – you alluded to your 2S deferment. What conscription existed, but students were left off the hook.

I mean to get into the other question is the draft, just specifically about the Vietnam War, the draft is what enabled Johnson to escalate the war very, very quickly. You know, because he had the draft, didn’t have to give any kind of permission and so on. So, you have a question – if you talk about it being more democratic, you have another issue which is why should it only be young people? People can volunteer for the military up to age 39 right now. So, why should the draft be limited to just young people? I believe we talked about disenfranchised. It’s because young people have much less political power. But if the draft were extended and actually people could serve in the military now until age 62.

So, if you’re going to have a real genuine egalitarian system, it should include everybody up to the age of 62. I’m just getting some of the reasons that the draft is not necessary. And really, whoever you pick for the draft, it’s not going to be fair, because, as I said, why should it only be young people?

There’s no good reason except for the fact that they’re the most disenfranchised. They have the least power of any other group, if you had to pick an age group. If you said that draftees were 45 years old, then there would be a whole different attitude about it

Michael: So, that is really, really good, Robert. And you also mentioned some connections before, which are very interesting, between the anti-war work that you participated in and the civil rights movement. I was just remembering that we had, at my campus, Berkeley campus, we had, of course, the free speech movement. And we won our issue in the Free Speech Movement. And with these big, huge rallies on Sproul Plaza with 20,000 people.

And then one of the last meetings for FSM, people were about to go home and Mario said – how did he put it? “Don’t go home, folks. We have a war to stop.” And so, that folded right into the resistance that you were talking about.

Robert: That’s true. Let me just go back to your previous question for just one second. Most people don’t realize it, but Congress is just about to expand the registration for the draft system to women. Well, without getting too technical, it’s almost to be approved and will probably be approved in November. Starting next year, young women are going to have to register with the draft.

The draft system still exists. The Selective Service still exists. All young men now have to register for the draft or register with Selective Service and register. And Congress is just about to expand that to include women as well. So that’s something that you should write your senators or congresspeople and say that you’re opposed to expanding it to women.

Because as I said, it’s unnecessary. It’s just another way that the military has, you know, being part of our system, being part of our lives.

Stephanie: So, just we want to let our listeners know that we are speaking with Robert Levering. He is an executive producer of “The Boys Who Said No!” Judith Ehrlich, the director, was nominated for an Oscar for this incredible documentary about draft resistance to the Vietnam War. It’s an incredible documentary. There’ll be an online gala for it on October 15.

Well, Robert, another thing that I really appreciated about the film was that I felt like these men and women who were participating in the draft resistance, it wasn’t just about ending the draft. It was about ending war. Like ending the draft was a strategy in order to end the wars. And then you have other strategies in there, where people are defending themselves in front of judges, without lawyers, and they’re standing there telling their reasons.

And they’re saying, “Well, we hope that if enough of us tell our stories that we’re going to move the hearts of these judges, and they’re going to stop giving convictions to people.” Right? So, just the idealism of a movement that thinks that it can actually end war. Not just the draft, but this is about ending war. I don’t know if we have that today. I don’t know if people feel that war is something that we can end because it is so embedded. And so, our fights are much smaller, right? Can you speak to this?

Robert: We just have to fight it in every way we can think of. About how it touches us. Right now I think the most important thing is to, you know, voice objections to how the military is encroaching. I mean there’s a number of things in terms of lobbying Congress that are important. Like right now, most people don’t realize it, but Biden suggested that the Pentagon budget should be a certain amount. Actually, it’s $715 billion next year. And Congress added another $25 billion in the bill that’s currently going on.

You know, people talk about how Congress is so divided. Well, they’re not divided in terms of the military-industrial complex. You have a totally bipartisan. You know, everybody is in lockstep about this. And I think that’s one area that we can say, “Hey, no. We should cut down the military.” There’s a bill that Barbara Lee sponsored to try to reduce the Pentagon budget by 10 percent. That’s the sort of thing where we have to fight it now. It’s going to be a lot of little things that – the way that the military has such a control over so many aspects of our lives.

And now this latest thing I mentioned, expanding the conscription system to include women as well. That’s involving another huge population.

Stephanie: So, Robert, you’re a draft resister. You’re nonviolent. You’re dedicated to nonviolence. You’re executive producer of this film, “The Boys Who Said No!” Tell us about the online gala and how people can go.

Robert: You can go to our website, which is boyswhosaidno.com. And that will give you the links for the gala. The gala – well, the way it works is that you go there and register. I think it’s $12. And that enables you to watch the film any time from Friday the 15th through Sunday the 17th. And then on Sunday the 17th at 2:00PM Pacific Time there’s going to be a panel – Zoom discussion which your registration will enable you to be able to see with David Harris and Joan Baez, Daniel Ellsberg and Judith Ehrlich, the director of the film.

That’s going to be, I think, a really interesting discussion. They’re going to be talking about the relevance of the draft resistance movement until today. Anyway, I highly recommend it. I mean, well, Stephanie, you seem to have liked the film.

Stephanie: Oh, I know. I really did. I really did. It was educational. It was focused on nonviolence. And it just shows how important this draft resistance was to ending war. I don’t know. I’m really glad that I got to screen the film, and I’m definitely going to go to the gala.

But I do want to thank you, Robert, for joining us today. Thank you so much for your time, and thank you for your work in nonviolence.

Robert: Thank you.

Michael: Thank you, Robert. Good to speak with you again.

Stephanie: So, you’re at Nonviolence Radio, and we are just finishing an interview with Robert Levering, Executive Producer of “The Boys Who Said No!” a film about draft resistance to the Vietnam War. There will be an online gala. You can find information for that from BoysWhoSaidNo.com.

So, let’s start off with a little nonviolence in the news. Michael Nagler, your Nonviolence Report. What’s happening out there in the world of nonviolence?

Michael: Thank you so much, Stephanie. Yyou know what’s happening more and more every time we do this program, it seems, is that we find we are in an era when the study and practice of nonviolence are expanding in a very gratifying way. And that could really – in fact, it will undoubtedly change history and change it for the better.

One of the things that’s happening is a growth of new organizations. I just noted three of them this is week. There are more coming online. One is called, “Regeneration.” Regeneration.org. And what they say is this is the world’s largest and most complete listing and network of solutions to the climate crisis, and how to do them, how to practice those solutions.

So, this is another, I think, a qualitatively new development in the world of nonviolence. That is the umbrella organizations, or the collaboration of different groups in different areas.

Of course, we should realize, if I may editorialize it there, that climate is a crisis. There is no question about that. But for a long time, the vast bulk of progressive energies have been going into climate, somewhat at the expense of direct violence in the form of war. Somewhat less direct violence in the form of mass incarceration, etc. So, this is a very useful model. I’d like to see that collaboration. Prior to this era, nonviolence has been kind of scattered, and the biggest setback there, the biggest disadvantage, has been that every time an event comes up, we react to that event. We have to reinvent the wheel. We have to reassemble our networks.

So, this enables us to maintain momentum and connection between events. And more importantly – I’m going to speak to this again in a little while – to shift from a purely reactive stance to one of taking proactive constructive steps. Okay.

So, that was one of the three organizations. Another one is called, “Momentum” which has joined recently with a third. I don’t know how new this one is, actually which is called the “The Indigenous Environmental Network.” You can find that in a website called, “Solidarity2020.” And there’s a very good article by our friend and colleague Stellan Vinthagen from Amherst with a very useful and directly applicable essay of his called, “Why We Need To Shift From Protest Power to People Power.”

People Power being, of course, the – how do you say – popular and scholarly name for nonviolence. I mean, my own contribution to the field has to been to suggest, yeah, people power is much more important and much more progressive than corporate power. But we have to realize that people power itself arises from person power, from an individual struggle to liberate the creative and nonviolent energies within us. I have this conceptualized in our Roadmap project in the Metta Center.

So, November 2 there will be a program on Pace e Bene, which is again, one of our longer standing, more venerable nonviolence organizations, Franciscan based. It’s called, “The Spirit of Nonviolence.” Isn’t that wonderful? The Spirit of Nonviolence. And it will be an online course on November 2.

Now, there is a controversial issue and I don’t want to get into the whole thing, of course, but that is the issue of abortion. Texas has made a move to render it illegal, which has been blocked by a federal judge. And this is a really vexing issue. It’s divisive not only between right and left, but within the right, within the left. And I’m remembering a formula – Bill Clinton on this – which I always thought was, you know, it’s sensible. It’s accurate. It’s useful. We should have made it into a mantra, if you will, for the movement.

He said, “That abortion should be affordable, safe, and infrequent.” So, we’re in an awkward position here because it becomes kind of a fig leaf for protection of life. And it disguises a control of women, taking away their ability to choose and tries to force, or has forced, some people into an awful dilemma of having to be – put choice ahead of life and actually – my personal opinion is, not that I have a solution to the problem that I want to offer here, but my personal opinion is that without choice, life becomes meaningless.

We are put on this planet to discover what our resources are, what our responsibility is. What was called in India – this is a very interesting concept or term. It’s called swadharma. As we all know, or we’ve all heard the term dharma which means “upholding, sustaining law or principle of the universe.” But the way the Indians worked out it is kind of on three levels, which I’ve always found really, really insightful.

You have an overriding dharma which applies not only to every human being, but to all life, eventually. And that is succinctly defined as Ahimsa Paramo Dharma. Nonviolence is that supreme law. All life has been leading up to it. It is the glory of the human being to be able to choose it.

However, within that overall dharma, you have what’s called, Yuga Dharma, or the dharma of every age. And it has been said by Gandhi and others that the dharma of our age is truth because there’s so much misinformation that people are left without a capacity to make a sensible choice. And as I’ve just said, that really seriously diminishes them humanely.

So, okay, that’s two out of three. So, we have the overall dharma, which is nonviolence. The dharma of each age. And I would also add the dharma of each culture and then when you get right down to it, there is this idea of swadharma or the dharma of every individual. The idea being that every single one of us is born with strengths and weaknesses, and we have the glorious opportunity to work on those weaknesses, convert them into strengths, which is another brilliant insight of the Indian sages, that every negative can actually be turned on its head. And its energy, its compelling power can be used positively.

Then each individual working out his or her dharma exercises the greatest responsibility in life, which gives us our meaning. And as we all know, life without meaning is no life at all. Here, I would recommend the famous book by psychiatrist Viktor Frankl who spent two and a half years is Auschwitz. He wrote a book called, Man’s Search for Meaning, which is really where I began to realize the importance of it.

Well, a couple of other things here at this point, Stephanie. I’d like to mention a couple of awfully good articles that have just appeared in TruthOut which is one of our major sources of alternative and sometimes nonviolent news. One of them is an article by Noam Chomsky. It’s called, “Chomsky: It’s Life and Death – Intellectuals Can’t Keep Serving the Status Quo.”

Well, this threw me right back to a much earlier book by a French writer called Julien Benda, called in French, La Trahison des Clercs, or “The Betrayal By the Intellectuals.” I snatched up the book when I first saw that title because I thought it meant betrayal of the intellectuals. I would say, “Yeah, yeah. Who’s betraying folks like what I want to be?” But no, it’s precisely what Chomsky is talking about, that when intellectuals lend themselves to the regressive force that takes us away from our dharma, even though they’re not activists, even though they’re not rabble-rousers, by and large, it is an important part of the whole spectrum.

And here’s a quote from Chomsky in this article, “It’s Life and Death.” He says, “The task of a responsible person,” which he defines as, “anyone who wants to uphold intellectual and moral values – is not to speak what they regard as truth to anybody – the powerful or the powerless – but rather to speak with the powerless and try to learn the truth.” In other words, he is reacting, of course, to the slogan, “Speak truth to power.”

And he says, “This is always a collective endeavor. And wisdom and understanding need not come from any particular turf.”

So, that was a clever turn of phrase which I’m just placing before you, more or less, without comment. Our job is not to speak truth to power, but to speak with the powerless to try to learn the truth. Yeah, I think those two things go together well.

I’m reminded that one of the reasons that Albert Einstein fled Germany was not the anti-Semitism that really hadn’t peaked yet, but that Hitler had sent a petition around that intellectuals – back on that topic – intellectuals had to sign and the petition stated that German culture is German militarism. So, that’s that embeddedness, if you will, that Robert was talking about.

So, I mentioned that there were two articles among several others that I wanted to highlight in TruthOut, this latest week. And this other article is called, “Channeling Spirit of Revolution, Chileans are Drafting a Democratic Constitution.” So, Chile, of course, has been an extremely important struggle and a laboratory for this kind of struggle, a class struggle. Back in the ‘70s, Salvador Allende was president, and he was basically destroyed by the Nixon administration. And then in the ‘80s, 1988, you had Augusto Pinochet who was essentially – well, he was extremely dictatorial. He’s living in exile now in Spain. And there was a popular uprising that put him out of power by one of those constructive, not particularly confrontational methods of a popular referendum.

So, it’s very important to watch this laboratory and what will become of it, and you won’t see much of it in the mass media. But our alternatives, PopularResistance.org, TruthOut, AlterNet, and so forth, I hope, will be following the process in Chile.

The other thing is that our friend, Margaret Flowers in Popular Resistance, has gotten a really relevant, important article called, “The Anti-War Movement Must Not Go Back to Sleep During the Biden Presidency.” I can talk about that quite a bit because it’s the importance of proactivism, of continuity, of being able to learn from one episode to the next and so forth. So, again, I recommend highly Margaret Flowers, almost as highly as I recommend the film, “The Boys Who Said No!”

Stephanie: Michael, thanks so much for the Nonviolence Report. We want to thank our mother station, KWMR, to you our listeners. Want to thank Matt Watrous who is going to transcribe the show. Bryan Farrell, who helps put it up at Waging Nonviolence. Annie Hewitt who does some editing on our transcript, thank you so much, especially to our guest today, Robert Levering. And to everyone out there, until the next time, please take care of one another.