As summer has turned to autumn, memories remain vibrant from the commemorations in June of the 50th anniversary of the Mississippi Freedom Summer at Tougaloo College, on the outskirts of Jackson. The word tougaloo in the language of the Choctaw Indians meant “here the waters divide” and refers to the fork of two creeks on the campus. I had lived in a tiny weatherboard house across from the gates of the college, established for freed slaves in 1869 by missionaries on the grounds of a slave plantation, while working on the 1964 freedom summer project. In this black enclave, I felt protected by the local community, which called us “Freedom Riders,” whether or not we had been on the 1961 freedom rides. Even so, I had planned 10 different routes for driving to and from Tougaloo College to the office of the Council of Federated Organizations, or COFO, in Jackson. Each day I changed which roads I took, because I believed that I might be targeted and under surveillance by night riders and vigilantes.

COFO was an umbrella group formed in 1962, which included not solely the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, but also the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and others. With unity a vital component of organizing that could challenge the widespread and random violence against black citizens, COFO ingeniously brought together all the human and organizational resources that could then be mustered in Mississippi.

Even though SNCC contributed approximately 80 percent of the staff and funding, with CORE supplying the remaining 20 percent, Bob Moses of SNCC and Dave Dennis of CORE worked tightly together. Dennis was a veteran of the sit-ins and freedom rides, and led CORE’s operations in Mississippi and Louisiana; he steered CORE’s participation in Freedom Summer. Working together, Moses and Dennis guided the whole project, which sought to reach all of the state’s 82 counties. It included some 30 voter registration projects, 38 freedom schools, the building or renovation of nearly 20 community centers, and the development of a parallel political party, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

These initiatives were what is known in the canon of civil resistance as alternative, or parallel, institutions, originally formulated in the Constructive Program of Mohandas K. Gandhi. COFO’s organizing of these alternative institutions — in education and helping the poor to organize their own credit unions and cooperatives before, during and after Freedom Summer — permitted black Mississippians to circumvent the constraints of racist oligarchies. At the same time, they could pursue social change while simultaneously withdrawing cooperation from repressive structures. These decentralized institutions would also serve as the foundation for a just society and lessen dependency on the adversary, proceeding toward a new social reality in the midst of the old. Voter registration was included among alternative or parallel institutions because it offered a widely accepted means of gaining political power.

Moses had proposed the concept of the Mississippi Freedom Summer to SNCC and COFO in autumn 1963. It would rest on the exertions of local communities that had for decades survived, suffered and struggled under Mississippi’s closed society, where the state’s endemic intermingling of institutionalized racism and violence were silently tolerated by the nation. A number of the most remarkable people that I have ever known were born into some of the most psychologically injurious circumstances in United States history — and they had persisted and prevailed.

One of them was Hollis Watkins, a national chair for the June meetings commemorating Freedom Summer and an alumnus of Tougaloo College, which had long sustained organizers, despite white supremacist pressures. He reviewed how between 1880 and 1940, the year before he was born, 600 black Mississippians had been lynched with no resulting convictions. In the 1940s and 1950s, 300,000 black citizens had left Mississippi permanently, emigrating to northern cities. Hollis had been running citizenship classes before meeting Moses while canvassing. “The struggle antedated us,” Watkins noted, saying that those like himself had joined others already at work, such as Ella Baker, Aaron Henry, Amzie Moore, and C. C. Bryant.

We were standing on the shoulders of giants, who in turn drew strength from their indomitable predecessors. For the summer project, through an active network of Friends of SNCC groups in Boston, Chicago, New York, Princeton, Seattle and other cities that helped with raising funds, a large number of young volunteers would be recruited to become civil rights workers. Local people were also encouraged to apply to enlist in the effort. In all, 1,500 staff and volunteers toiled in project offices across the state; approximately a thousand of them were students volunteering from northern colleges, hundreds of whom acted as teachers in the Freedom Schools, working with more than 3,000 students during the summer.

According to archives in the Wisconsin State Historical Society, where many of us would later donate our papers, the Medical Committee for Human Rights had projects in seven counties, for which it recruited perhaps 50 physicians, nurses and other clinicians. The National Council of Churches sponsored more than 250 clergy over the summer. Some 169 attorneys were recruited by the National Lawyers Guild and Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee. The volunteers were directed by 122 SNCC and CORE paid staff, who were working alongside them or in the COFO headquarters in Jackson and Greenwood. Overall they came from 48 states — including large contingents from California, Illinois, Michigan and New York — and five foreign countries.

On June 21, 1964, the first day of the summer project, three Freedom Summer workers disappeared: Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner. Chaney was affiliated with CORE and in charge of supervising Goodman and Schwerner. The three workers had left Meridian that morning to drive to Philadelphia in Neshoba County in the central part of the state, to investigate the recent arson of Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church and the whipping of three local black individuals there.

As I was working in communications, the responsibility fell on me to telephone the families of the three missing men and let them know that we suspected foul play. I was filled with foreboding but found the strength to telephone the Chaney family and the Goodmans. (Schwerner’s wife Rita was a stalwart teacher in one of the freedom schools and already aware.) It was also my job to call every jail and prison in the vicinity of Neshoba County and ask whether they were holding the young men in detention, as I recount in Freedom Song: A Personal Story of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. I systematically called every lockup and detention facility in the counties surrounding Philadelphia — Lauderdale, Kemper, Leake, Winston, Neshoba and Newton counties. Painstakingly, I phoned every police headquarters and sheriff’s office, plus the mayors of small towns in the six-county area, to ask if they were holding the three men. Under customary law, officers were expected to acknowledge whomever they held in custody and to disclose the charges under which they were held. Those holding the men lied to me. These telephone calls took hours. At 1:00 a.m. I called John Doar of the Justice Department. Sometime after 1:30 a.m., and exhausted, I turned over the calling to a new volunteer named Ron Carver.

When efforts began to dredge the Pearl, Tallahatchie and other rivers to find the bodies, many other corpses were found, frequently with their hands tied behind their backs. Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were later found dead, killed by law officers. (Not until 1967 would Neshoba County deputy sheriff Cecil R. Price and six other defendants be convicted. Rather than being charged with murder — a crime normally adjudicated at the state level, but unlikely to return justice in a system that is still permeated by racism — they were prosecuted for denying the workers’ civil rights under federal statutes.)

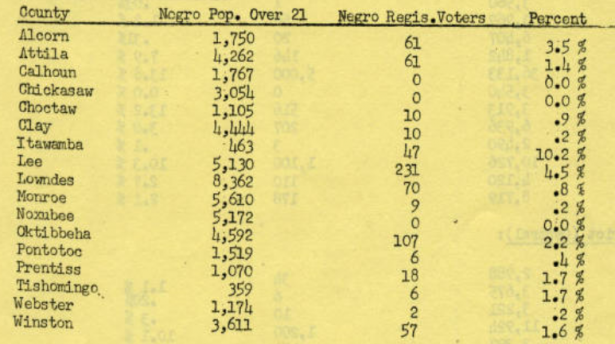

Despite the enormity of this setback, we proceeded to build upon the deeply rooted tenacity and determination of approximately 60,000 local people who were directly affiliated or engaged with us, and with whom we shared a commitment that Mississippi’s systemic racism and violence must be confronted. As thousands of black Mississippians defied intimidation to enter county courthouses that summer, comparatively few would be able to register to vote. Historians believe that roughly 17,000 tried, and 1,600 succeeded in registering. Those who made the attempt were regularly penalized by their employers, lost their jobs, or were beaten by the vigilante and terror groups that were often in collusion with law authorities for daring to violate the local oligarchs and norms of segregation. Such embedded opposition to the pursuit of constitutional rights had persisted since the failures of the Reconstruction period, which were never coherently confronted. This was a major justification for the summer’s mobilization. Years later it would emerge that approximately half the state’s law officers had been affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan.

Even so, during Freedom Summer, for the first time, the harassment and reprisals against would-be voters were widely covered in U.S. news media. National indignation helped to intensify support for new legislation and the minimalist federal intervention that had been so long in coming. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in education, employment, and public accommodations. Without question, the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was boosted by Freedom Summer. In August 1964, millions had watched as Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who became an icon for the movement, testified on the challenge by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to the seating of the all-white regular Mississippi delegation at the Democratic Party’s national convention in Atlantic City, N.J. The parallel party had elected its own 68 delegates but was offered only two at-large seats, which the delegates rejected. In essence, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was spurned by the leadership of the national party. Yet virtually the entire country heard Hamer tell of being beaten and tortured for attempting to vote. The 1965 legislation, which prohibited arbitrary voting restrictions and empowered the federal government to intervene at the local level, is under new threats today.

To me, the best part of the conference at Tougaloo College in June was the meeting of Freedom Side, which was taking place alongside it, in the chapel. Freedom Side is a group of young organizers from Florida, Mississippi, Ohio and Texas, who have been working to mobilize communities, beginning this past summer, as a living commemoration of the 1964 Freedom Summer. Their name comes from the freedom song, “Which Side Are You On?”

I had spent time this past spring with perhaps 30 of the Freedom Side organizers, including a dozen communications fellows, who have been doing the same work that Julian Bond and I did 50 years ago. The Freedom Side organizing has proceeded into autumn, as these organizers work on issues such as juvenile justice and the cradle-to-prison pipeline in Florida, the deportation of the children born to parents who are unregistered in Texas, voter registration in Mississippi, and other crucial issues. The Ohio organizers prevented “Stand Your Ground” legislation from being introduced there, by organizing nonviolent actions across the state. This month, in Illinois, Michigan, and North Carolina, the Black Youth Project, which is part of Freedom Side, has begun a project to increase the black youth vote in those three states.

It is also true that the young people whom we recruited as volunteers in 1964 would today in many instances be unable to volunteer, with student debt in the United States now larger than credit card debt. Half a century after Freedom Summer, it is not only the young who should confront ongoing pernicious practices of racial discrimination, including the creeping weakening of the Voting Rights Act. The entire nation now has an opportunity to recast its democracy by encouraging greater citizen involvement in elections. Much like Scotland, where 80 percent of the population voted in their recent referendum, retaining the United Kingdom, the recognition of the importance of voter turnout needs to be reawakened now.

Districts and races where black voter turnout could be decisive this autumn are many. They include at a minimum the North Carolina Senate race, the quest for the Florida governor’s mansion, the Georgia gubernatorial and Senate races, the Arkansas Senate seat, and the Louisiana Senate contest. Considering the extremely high price that was paid 50 years ago to remove outrageous obstacles to basic rights in Mississippi and elsewhere, we must do more than sit on the sideline indulging in recollections. The exertions of half a century ago that awakened the nation and rallied proponents for justice from across the country are best honored by organizing to assure that all Americans exercise the most fundamental and basic right: the vote.

Mary Elizabeth King is one of my heroes – an extraordinary woman with profound insights into the meaning of the work she has been engaged in for more than 50 years. I’m particularly moved by the way she turns reflections on history into a call for action. We are fortunate to have her voice urging us on over the decades. Thanks, Mary, and Waging Nonviolence for including her in our inboxes!

Thank you so much, dear Mary, for sharing with us your unique experience… You are such an inspiration and an example for all the young activists engaged in the struggles of our times! You have the same passion and the same flame as 50 years ago, which you have carried throughout your academic carrier… Your courageous engagement at SNCC back then, and your continuing passion and commitment for justice ever since, have nourished your scholarship, making it so profoundly human, adding heart and soul to your sharp intellectual analysis of civil nonviolent movements… It is a privilege to know you, and to work with you! You are my inspiration and one of my heroes too!

This is great! keep up with good work!