This is part two of a series commemorating the 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth. The first, which focused on Gandhi’s life and work in South Africa, can be read here.

After 20 years in South Africa, Mohandas Gandhi returned to India on January 9, 1915. He was a different man from when he left his homeland as a shy teenager. He had evolved from being a British-trained lawyer — influenced by the racism of the empire — into an organizer, moral philosopher and political leader able to apply his unique experience and insights to the challenges faced by the people of the Indian subcontinent.

Little more than four years after his return, Gandhi would be tested by a major crisis. On April 13, 1919, a catastrophic massacre occurred in Amritsar, Punjab, at the Jallianwalla Bagh enclosure, a walled seven-acre garden area closed in on all sides. While unarmed mostly peasants peacefully celebrated a Hindu festival, British Brigadier General Reginald E. Dyer, without cause, gave orders to troops of the British Indian Army to fire. (The people of the subcontinent had been disarmed in 1857–58, after a mutiny against the British.) Gandhi’s associate Pyarelal later wrote, relying on government sources, that more than 20,000 men, women and children were trapped, as 379 were slaughtered and almost three times that number wounded. Horrified, Gandhi admitted to making a “Himalayan miscalculation” in underestimating the forces of violence — a confessional phrase he would use intermittently when admitting error. Cause and effect can be obscure, but not in this case, as his loyalties to British rule dating from young adulthood collapsed.

Gandhi contradicted himself, had inconsistencies, sat astride dilemmas and was extraordinarily open about his own human frailty.

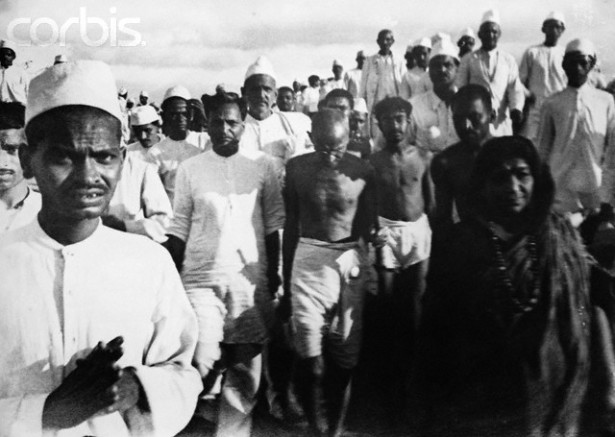

It was only a matter of time until British imperial dominion in India would end. Ahead lay Gandhi’s catalytic role in national all-India civil disobedience movements during 1920–22, 1930–34 and 1940–42. No longer seeking reconciliation, he was galvanizing momentous pressures to produce social change, with scant violent episodes. Regrettably, observers of what was happening in India from the 1930s into the 1950s tended to view and characterize Gandhi as a spiritual inspirer, ignoring or not seeing what he himself called the technique, method or process of struggle that he was refining. Bestowed with the title mahatma (Sanskrit for “great soul”) while in South Africa, a term of homage that made Gandhi uncomfortable, onlookers attributed his achievements to personal charisma, often oversimplifying his thinking as limited to nonviolence as a matter of principle rather than a form of social power. Early analysts overlooked his discernments regarding consent and popular power, meaning the power from the people, as well as his challenges to mainstream political thinking that then — as now — assumes a separation of means and ends.

Even during the 1920s as Gandhi’s profile rose on the subcontinent, he found himself subjected to opposition and controversy for virtually every statement made and action taken, in some ways little different from the allegations made today of racism. His sincerity was questioned on his work against untouchability, with unending controversies about his well-known asceticism and quirky personal traits. Responses to Gandhi were and are still intense. Even so, Gandhi’s willingness to criticize himself was a compelling attribute. He contradicted himself, had inconsistencies, sat astride dilemmas and was extraordinarily open about his own human frailty.

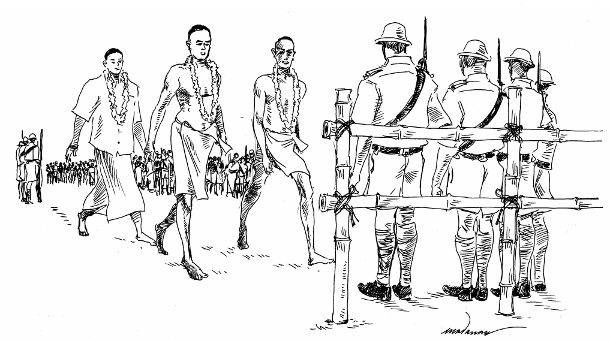

As an example, in February 1922, when preparing for national civil disobedience, Gandhi suspended an immense satyagraha campaign because village dwellers in Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh, set fire to a police station, killing 22 officers inside it. He had developed “satyagraha” while in South Africa, perturbed as he was by English speakers who talked of “passive resistance,” because submission played no part in his technique. Turning to Sanskrit, he bonded satya, or Truth, which for Gandhi meant justice, with agraha conveying firmness, force, or persuasion. For today’s reader, satyagraha can best be understood as corresponding with nonviolent direct action or civil resistance. Ruing his inadequacies in preparing the populace, Gandhi called the violent outbreak a “Himalayan blunder” and undertook a five-day fast of penance, despite being condemned for ruining a countrywide campaign due to one incident occurring among 700,000 villages.

Earnest missteps on untouchability

Unambiguously opposing abuses associated with caste and untouchability, Gandhi showed his seriousness regarding eradication of untouchability by welcoming a so-called untouchable family into the Sabarmati Ashram, formed at Ahmedabad in 1915, as a communal settlement, retreat, sanctuary and place of seclusion. He also adopted an “outcaste” girl.

However, he made a misstep in perceiving that Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar — himself a so-called untouchable, who would become the spokesperson and standard-bearer for those without caste — was an upper-caste advocate for the Dalits. Ambedkar was an economist, jurist, and political scientist who had been able to earn doctoral degrees from prestigious British and U.S. universities, notwithstanding the unreasonable handicaps faced by those without caste in the early 20th century. Gandhi mistook him for an upper-caste advocate, trying to act on behalf of those without caste, which had an alienating effect on Ambedkar. Dalit is a term from Ambedkar’s mother tongue. Some Dalits never forgave Gandhi for his misperception.

Previous Coverage

Gandhi and the myth of conversion — The Vykom satyagraha revisited

Gandhi and the myth of conversion — The Vykom satyagraha revisitedThough untouchability was found everywhere in India, the Travancore princely state — which was later incorporated into the state of Kerala — condoned practices of extreme caste prohibitions not observed elsewhere, including unapproachability and unseeability. Gandhi was invited to advise the 1924–25 satyagraha pressing for opening roads around a Brahmin temple to all Hindus in the village of Vykom in Travancore. Yet he committed serious errors of judgment, including rejecting outside assistance and proscribing anyone not Hindu from participating, even if only in support functions. He sacrificed 19 key leaders to imprisonment, leaving the struggle directionless, by insisting that “conversion” of the upper castes could be prompted by the poorly-formed notion that attitudinal change would result from their witnessing the suffering of those without caste. No archival substantiation whatsoever can be found that hearts and minds of the upper castes were altered by the end of the campaign, except in an abstract long-term metaphorical sense. Yet despite these and other mistakes, Gandhi’s involvement would result in the maharajah’s 1936 decree opening not solely the roads but all temples in Travancore.

In 1920, Gandhi wrote in Young India, “We shall ever have to seek unity in diversity,” as he wrestled with inter-marriage and inter-dining restrictions of the caste system. A century later his phrase “unity in diversity” is extolled in cultures and languages worldwide, pertaining to any exclusions. Gandhi bestowed an honorific on the so-called untouchables, calling them Harijan, Gujarati for “child of God” and in Sanskrit “embodiment of God.” The move later provoked disputes, as many who heard it found it patronizing, and it is no longer in daily use. Meanwhile, some states, including Kerala, have banned the term Dalit.

Gandhi’s rejection of a 1932 government proposal to create separate electorates for what the British called “depressed classes” (untouchables) came to be a source of criticism from those who allege that he was an apologist for the Hindu caste system. Ambedkar had primarily persuaded the British to accept the concept and was the person most consumed with the idea of distinct constituencies, as a way that Dalits could vote for their own leaders. Gandhi, however, feared what in modern parlance we might call rejectionism or separatism, in which those without caste would be driven even further away from the Hindu fold.

Although Gandhi had fasted often for various purposes, it was always for a defined period of time. He now embarked on a “perpetual fast unto death from food of any kind save water,” with an unlimited timeframe. An alternative electoral procedure was struck at Gandhi’s bedside in which voters from the so-called depressed classes would hold a preliminary election to choose four candidates empaneled for each seat in the legislatures of the British India government, and they would present themselves in a joint election by Hindus with and without caste. On September 24, 1932, as Gandhi’s condition worsened, this arrangement, known as the Poona Pact, was accepted by the British government, having been signed by 22 witnesses in Gandhi’s presence — including Ambedkar authorizing on behalf of the depressed classes. This doubled representation for Dalits in provincial legislatures while revising the electoral system, leading historian B.R. Nanda to conclude that abandoning of separate electorates for those without caste was “the beginning of the end of untouchability.”

Gandhi’s deep commitment to ending untouchability cannot be denied, nor the earnestness and tenacity of his efforts to induce social change for those without caste. Yet in Travancore during 1924–25, and in Poona in 1932, it is fair to say that Gandhi did not quite resonate with the impulses of the Dalits themselves, as they sought to transform their own condition. Their self-help anti-untouchability campaigns were in some ways beyond his understanding.

With age, Gandhi became increasingly distressed by practices associated with the caste system. In 1941, he wrote of the “awful isolation” caused by untouchability, “such isolation as perhaps the world has never seen in the monstrous immensity one witnesses in India.” Scholars of Gandhi contend that he wrote more against untouchability than on any other subject. Though when his critics claimed that he failed to confront the Hindu caste system with vigor, it held some truth, as he never made an aggressively frontal attack on caste. He was held back by fear of provoking upper-caste denial.

Previous Coverage

Gandhi and the Dalit controversy: The limits of the moral force of an individual

Gandhi and the Dalit controversy: The limits of the moral force of an individualM.G.S. Narayanan and other historians whom I interviewed in Kerala consider that while advising the Vykom struggle in 1924–25, Gandhi was conservative, cautious and wary of moving uncompromisingly against untouchability. Among critical reasons given by several Keralan historians was his conviction that significant change would require public repentance by upper-caste Hindus, expressing remorse for the bitter suffering they had caused to generations of those without caste. During the 1920s and 1930s, Gandhi spoke of atonement repeatedly: “To remove the curse of untouchability is to do penance for the sin committed by the Hindus of degrading a fifth of their own religionists.” By 1945, he had concluded, “The caste system as it exists today in Hinduism is an anachronism.”

In 1996, in a letter to me, historian Nanda wrote, “Gandhi’s lifelong campaign against untouchability brought the most depressed sections of Indian society into political awareness. It was not only the untouchables, but even middle-level castes which were affected; it was a transition from élite politics to mass politics.”

Nevertheless, India’s news outlets offer daily evidence for how people who have fallen through the bottom of Indian society as a result of the caste system are still subjected to appalling discrimination. Last year, newspapers reported a Dalit was scalped because he had asked for fair wages. Ironically, the fact that Gandhi has been lauded as the “Father of the Nation” and is engraved on India’s currency, locates him in the spaces of everyday life where he can be chronically disparaged by those who perceive him as deficient on ending untouchability.

Putting the nation ahead of the hearth

Gandhi was a captive of a patriarchal worldview still constraining India. For example, he held an essentialist perspective about what is inborn in the basic natures of men and women, which cannot survive scientific vetting. Consistent with Jain religious thought, he sought sublimation of sexual desire, leading him to recommend restraint. This also prompted behaviors such as sleeping next to his grandniece and other women to test his self-control, now a favorite choice for attack by some of his critics. However, he also opposed contraception. Yet in other important ways, Gandhi’s outlook was advanced. Having been married in vows arranged by his parents at age 13, from within orthodox Hinduism he attacked social “evils” including child marriage as “unspeakable and unthinkable sin.”

Gandhi was outspokenly opposed to dowry (payment of money or property the wife brings her husband, the absence of which has resulted in dowry-related violence) and purdah (a system of seclusion of women from public observation by means of walled enclosures or screens). He also denounced the severe restrictions on widows. Social scientists report that some 40 million widows are currently enduring extreme forms of discrimination, dire enough that India’s Supreme Court in 2012 ruled that the government must provide them with food, medical care and sanitary living conditions. Gandhi openly addressed attitudes of male superiority toward women and called for women to have equity even if illiterate.

Early in life, Gandhi’s reasoning was that of an upper-caste, middle-class man who thought women should be cloistered at home, while ignoring that most Indian women then were forced by necessity to earn livelihoods by working in fields and laboring in factories. His outlook was conventional on gendered allocations of housework. Even so, his South Africa experiences brought him to rank the nationalist cause ahead of the hearth in advocating women’s leadership. By 1921, he was calling on women to become involved in national political deliberations, to secure the vote and to press for legal status equivalent to men.

By the late 1920s, Indian women were leading local struggles on the subcontinent. Gandhi encouraged the nationalist poet Sarojini Naidu’s appointment as president of the Congress Party at a time when few women anywhere led political parties. During the 1930 Salt March, Naidu was the first to be arrested among the 17,000 women jailed for participating. Later, she became the first woman governor of free India.

While not equating the enormity of Gandhi’s political efforts to abolish untouchability as comparable to his concern for women, historian Ramachandra Guha concludes that during 30 years of work in India Gandhi personally and significantly brought about alterations in customary gendered hierarchies. Ahead of his time in making this a priority, Gandhi asserted in 1918, “So long as women in India remain ever so little suppressed or do not have the same rights [as men], India will not make real progress.”

Historian David Hardiman contends, “Fellow nationalists and women activists never subjected Gandhi to any strong criticism for his patriarchal attitudes. In this, we find a contrast to his other major fields of work, in which sharp differences were expressed in a way that forced him to often qualify or modify his position.” Had Gandhi been more assiduously challenged about failures to deploy the creativity of woman, his attainments might have been even more admirable in recognizing their salience as agents of social change.

Gandhi’s 1941 book “Constructive Program” sought to accomplish a social order aimed at interlocking goals of societal reconstruction. Though conceptually potent and ultimately more important to him than resistance, his presentation was sketchy and unsystematic. He saw political independence as requiring comprehensive undertakings by millions, including the construction of decentralized institutions to serve as the infrastructure for a just society. Its most trenchant feature was that it allowed advancing toward a new social reality in the midst of the old.

The hand-looming of khadi, or khaddar, hand-spun cotton cloth of village production, was among 17 components that would help the poor to decentralize economic production, while nationally (at least symbolically) freeing the country of dependency for textiles on British mills. Also included were cottage industries making soap and paper; village sanitation; adult education; and labor unions committed to nonviolent action. Critics have said the only source of earning for women that Gandhi could advance was hand-looming, which has some validity. Yet it can also be said that millions of women participated in the national struggle (however emblematically) by making homespun cloth, even if poverty stricken or sequestered under purdah.

Fervent opposition to India’s partition

Every historical era has its own touchstones for determining what was considered reliable knowledge and defensible truth. The Hindu-Muslim question on the Indian subcontinent long antedated Gandhi’s ascendance. Yet Hindu absolutists are heard today blaming Gandhi as having been sympathetic to the country’s Muslim minority, accusing him of promoting Pakistan’s separation from India during partition.

Those who hold Gandhi responsible for the severing of the Indian subcontinent seemingly ignore the role of the British. On February 20, 1947, a decade after recommending the partition of historic Palestine, setting in motion several wars and military occupation, Britain again promoted partition as a solution to a problem it had partly created. Its plan provided for the British to transfer power to two states, India and Pakistan, implementing partition on Aug. 15, with only two and a half months for effectuating complex transfers of power. Recent research suggests that this timeframe affected the accompanying catastrophes that led to between 10-12 million persons being displaced, with perhaps two million mortalities.

Embittered controversies raged as the Muslim League put forward a two-nation theory and the secession of the Muslim-majority areas in the northwest and northeast to create Pakistan. Gandhi’s view was that dividing the country was not in the interest of the Muslims, who comprised one-quarter of India’s population, or that of the non-Muslims. He believed it detrimental for the future. Nanda wrote of Gandhi, “His opposition to partition was an open secret.”

Anyone who seriously examines the public record of Gandhi’s life cannot question the intensity and duration of his labors to prevent the severance of India. He worked intensively for nearly two years to temper communal fanaticism, from October 1946 almost to the moment of transferring power from Britain.

Gandhi’s consequence today

Some of Gandhi’s views about transforming conflict are more applicable today than in his own era. He understood that strife cannot be eradicated like a disease and also grasped the more important reality that it can be rearranged, managed and made less deadly. To be sure, civil resistance does not mean the settlement of disputes, although this may be one outcome from a nonviolent struggle. Indeed, actual “resolution” of conflict rarely occurred with Gandhi. Some condemn him for “managing” acute disagreements, akin to dealing with a chronic condition. Yet learning to manage deadly discord is fully compatible with the field of peace and conflict studies as it has gained authority in the 20th and 21st centuries. Acute strife is now more readily understood as being susceptible to rearrangement, able to become less destructive, contained, redefined, or downgraded, rather than presuming the rarity of resolution.

Gandhi gathered from his own experiences that nonviolent methods are effective regardless of whether they are religiously motivated. He appreciated that nonviolent mobilizations are composed of people with immensely diversified beliefs, principles and creeds. Rather than expecting that everyone on the Indian subcontinent share his own religious scruples and personal regimen, he asked for adherence to the policies for nonviolent action. A pragmatic understanding of the practice of civil resistance was acceptable for Gandhi, as he expressed in his 70s. “I admit at once that there is ‘a doubtful proportion of full believers’ in my ‘theory of nonviolence,’” he wrote. “[F]or my movement I do not at all need believers in the theory of nonviolence, full or imperfect. It is enough if people carry out the rules of nonviolent action.”

Previous Coverage

How did Gandhi win?

How did Gandhi win?In today’s world, the turn to civil resistance is growing. Its practitioners presuppose that political conflict cannot be eliminated and thus they increasingly tend to turn to Gandhi’s substitute method for creatively facing violent discord. This technique relies on a philosophy of action and conscious noncooperation — the withholding, suspension or discontinuance of obedience and cooperation — either spontaneous or planned, legal or illegal.

Gandhi was a product of his time and therefore had certain limitations. His consciousness was anchored in a mindset of experimenting with nonviolent action. Some allegations of racism against him give the impression that he was not paying enough attention to black struggles. Yet he was not a traveling salesman peddling theories but avoiding certain neighborhoods. Neither an ideologue nor theoretician, he saw his experiments as leading to potentially universal application, and in fact his discernments provided much more than mere sustenance to the U.S. civil rights movement.

By the 1920s, pockets of black communities in the United States were reading newspapers owned by African Americans that avidly covered Gandhi’s adoptions of strategies for resisting oppression, which might be applicable for them. Historian Sudarshan Kapur’s 1992 book “Raising up a Prophet” shows how black leaders traveled from 1919 to 1955 on 12,000-mile sea voyages to India for study of its nonviolent struggles. Some of the trail blazers met with Gandhi. Concepts and lessons were exchanged in an interaction between two freedom movements, one in full velocity, the other emergent, while Indian figures also spoke in the United States.

Using today’s standards in judging someone or events occurring within a period wholly different from our own, without appropriate contextualization, cheats comprehension of two realities: first, human beings evolve, and second, today’s world is dramatically different from that in which Gandhi labored for two decades in South Africa and for 30 years in India.

Gandhi became tutor to the human race on the forces made operative through social power.

What are now called boycotts, strikes, and other forms of civil resistance were being used in ancient Rome and Egypt, and elsewhere in antiquity. Yet the worldwide historical turning point for knowledge of the practice and theory of nonviolent action is Gandhi. Recognition of embryonic conceptions of human rights and expansion of concepts of equality benefited from the transformations of conflict led by Gandhi in South Africa and India, which placed nonviolent struggle on the world political map.

So-called “universal” human rights often begin with massive nonviolent movements fighting for their recognition, only later to be codified in human rights laws and international conventions. Minority rights, women’s rights, rights of the disabled, and other advancements have been institutionalized as a result of campaigns directly or indirectly indebted to Gandhi’s provision of a foundational technique for addressing human conflict that can be used by average people. (Laws alone are insufficient and often enshrine wrongs; time and again the most cruel and barbaric practices of gendered inequities are perfectly legal.)

Applying the core sanction of noncooperation, Gandhi became tutor to the human race on the forces made operative through social power. With their civil society leaders often utilizing his writings in the process, within the past half-century more than 50 countries have made democratic transitions from tyrannies and dictatorships. Historian David A. Bell contends, “Since the 1970s, the idea of human rights as the basis for how states should behave has profoundly transformed international politics.” That nation-states have for over 70 years benefited from Gandhian insights is a reminder of the folly of applying present-day standards and ideals to individuals who lived in past eras.

Advocates for Gandhi’s methods nowadays are generally not found in elected office, although parliamentarians, mayors and governors, chosen by ballot as office-holders, have themselves used civil resistance in parliaments and government departments, termed “constitutional action.” Gandhi’s successors currently are fighting systemic and technological debasement of democratic governance, rectifying corruption, cleansing democratic elections, battling nativism and neo-nationalism, and assailing white supremacy and the fallacy of racial inferiority — quandaries being deepened and worsened by misinformation rapidly and irresponsibly spread by social media. Contemporary Gandhi apprentices — some of them in their teens — populate environmental networks fighting climate heating. Other inheritors safeguard traditional rural areas, build alliances against impoverishment, pursue women’s equity, and further religious harmony and human rights for all, including the LGBTQ community. Their numbers are growing.

Among Gandhi’s most notable traits was his admission of vulnerability to error. Demonstrating appealing strength of character, some editions of his 1909 “Hind Swaraj,” or “Indian Home Rule” include his note to the reader: “I am not at all concerned with appearing to be consistent. In my search after Truth I have discarded many ideas and learnt many new things … [W]hen anybody finds an inconsistency between any two writings of mine … choose the later of the two on the same subject.” Can this be considered an invitation to focus on learning from Gandhi’s errors rather than judging them?

Gandhi was a person of color himself, who had to struggle with internalized racism, conditioned prejudices, and unsubstantiated perceptions of purity and pollution. Yet he was able to demonstrate throughout his adult life his willingness to learn and teach what he had differentiated through testing and experimentation. The selective adoption of Gandhian insights, procedures, methods, and practice within the U.S. freedom movement has reverberated to innumerable other nonviolent struggles worldwide. This reality perhaps makes perceptible Gandhi’s parting statement to Professor Howard Thurman, of Howard University, and his wife Sue Bailey Thurman: “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Gandhi’s Truth Force was good enough for WWII pacifists, sitting out the war.

And once the war ended, many took it further, in pacifist activities and the civil rights movement. Jim Peck himself campaigned against segregated dining halls while in prison. Bayard Rustin was a key player in bringing non-violence to the desegregation movement, after doing prison in WWII.

Gandhi’s lack of vision doesn’t discount his impact on civil disobedience. Bayard’s homosexuality doesn’t deny his importance, and the civil rights movement keeping Bayard behind the scenes because of that doesn’t deny it’s importance to us all.

It’s okay to write about Gandhi’s limitations. But lately people seem so willing to erase people because of something they did wrong, rather than accept their importance without avoiding the bad.

Don’t put people on pedestals in the first place because few are perfect.

I can read about people and make my own judgement, but I don’t need them erased.

Michael