Near the village of Vykom in South India over a period of 604 days in 1924-25, mixed teams of Dalits and caste Hindus faced arrest, beatings and appalling hardship as they attempted to walk on roads encircling a Brahmin temple. Their actions were in defiance of a prohibition by the temple authorities, enforced, as were other caste laws, by the state authorities. It is probable that, like this reviewer, many readers will have accepted a misleading narrative of this famous campaign which was promulgated — albeit in good faith — by a succession of writers on nonviolence and Gandhi, from Richard Gregg in his 1934 classic “The Power of Nonviolence” to Krishnalal Shridharani, Bart de Ligt, Joan Bondurant and Gene Sharp. According to this narrative, the Brahmin guardians of the temple were finally moved by the nonviolent persistence and endurance of the participants in the struggle, or satyagrahis, to accede to their demands for the road to be open to all regardless of religion or caste.

Near the village of Vykom in South India over a period of 604 days in 1924-25, mixed teams of Dalits and caste Hindus faced arrest, beatings and appalling hardship as they attempted to walk on roads encircling a Brahmin temple. Their actions were in defiance of a prohibition by the temple authorities, enforced, as were other caste laws, by the state authorities. It is probable that, like this reviewer, many readers will have accepted a misleading narrative of this famous campaign which was promulgated — albeit in good faith — by a succession of writers on nonviolence and Gandhi, from Richard Gregg in his 1934 classic “The Power of Nonviolence” to Krishnalal Shridharani, Bart de Ligt, Joan Bondurant and Gene Sharp. According to this narrative, the Brahmin guardians of the temple were finally moved by the nonviolent persistence and endurance of the participants in the struggle, or satyagrahis, to accede to their demands for the road to be open to all regardless of religion or caste.

In a new, authoritative and extensively researched book “Gandhian Nonviolent Struggle and Untouchability in South India: The 1924-25 Vykom Satyagraha and the Mechanisms of Change,” Mary Elizabeth King tells a different story. The temple authorities, far from being converted by the voluntary suffering of the volunteers, hardened their stance. It was the Vykom government — under mounting political pressure — that eventually accepted a compromise deal brokered by Gandhi, though one that fell far short of the demand for all the roads encircling the temple to be open.

In the opening chapters King outlines the caste and class structure of the princely state of Travancore, which is now part of Kerala. The picture that emerges is of an incredibly complex hierarchy. The central division was between the savarnas, who enjoyed caste status, whether high or low, and the avarnas who were outside the caste system altogether — also known as Untouchables (probably an English term) and more recently called Dalits, which means the “broken ones,” the term preferred by one of their leading spokespersons, Bhimrao Ambedkar — and occupied the bottom rungs of society.

The Brahmins at the top of the caste pyramid belonged mainly to the principal landlord class, called the Nambudiris in Travancore, a tiny proportion of the population who nevertheless owned most of the land not under direct government jurisdiction. Immediately below them in status and wealth were the Nairs, constituting approximately one-fifth of the population, who administered the Nambudiris’ lands, dominated the legislature, and held the largest number of posts in the civil service.

The Dalits, too, were further stratified in terms of social status and the degree of “pollution” with which they could supposedly contaminate the higher castes. And while the caste system existed throughout India, it was more highly stratified and rigidly enforced in Travancore. Only there were two additional sub-categories of untouchability recognized — “unapproachability” and “unseeability.” Unapproachables “polluted” caste Hindus by being anywhere in their vicinity and when using public roads had to shout loudly as they walked to warn savarnas of their approach; unseeables polluted savarnas simply by being seen and thus would come out only at night.

Paradoxically, Travancore was also noted for its high level of tolerance of non-Hindu faiths and its educational standards, which resulted in its having the highest literacy rates of any state or region in India. The gulf between educational achievement and employment and career opportunities — severely restricted along caste lines — led to discontent and demands for change, especially among the largest and most highly educated of the Dalit groups, the Ezhavas. This sub-caste had become relatively more prosperous during the 19th century as they came to occupy posts in trading and small industries generally looked down upon by caste Hindus. The Ezhava People’s Assembly was founded in 1896 to improve the standing of avarnas and was the forerunner of others, most notably the SNDP Yogam, founded in 1903 by Sri Narayana Guru as the Sri Narayana Dharma Periplana Yogam, which became the major Dalit campaigning organization; by the 1920s it had achieved the status of a mass movement. A number of Ezhavas with the necessary property qualifications also became members of the official Consultative Assembly set up in 1904 to advise the Maharaja, thereby giving the community a public forum where it could press its demands. These were some of the developments that set the stage for the Vykom satyagraha, or campaign of nonviolent resistance.

In 1923, the Indian National Congress invited a leading Ezhava campaigner, T.K. Madavan, to address its annual meeting and, following his address, set up the Anti-Untouchability Committee. In February of the following year this committee decided to launch a campaign of intensive propaganda to eradicate untouchability, including a petition addressed to the Maharajas of Travancore and the neighboring princely state of Cochin, and processions by volunteers of mixed-caste composition along prohibited roads, starting with the temple roads at Vykom. Gandhi did not himself take part in the Vykom satyagraha, but the organizers looked to his example in the national noncooperation campaign of 1920-21, and actively sought his advice. He cautioned against mass civil disobedience as being too confrontational in the context of a princely state, enjoined a policy of strict nonviolence, and advised the satyagrahis to seek to bring about the desired change not by any kind of compulsion, but by melting the hearts of the Brahmin guardians of the temple through voluntary self-suffering.

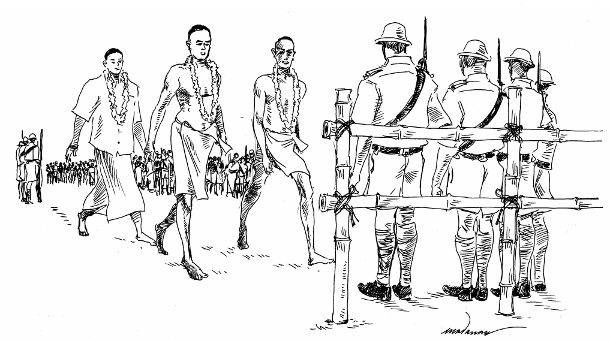

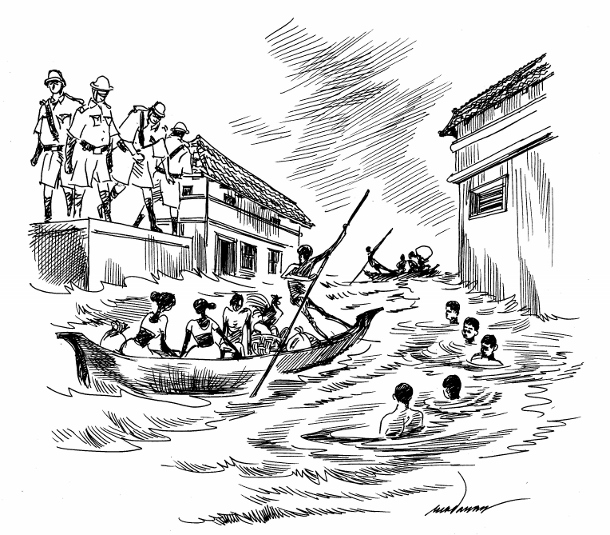

The satyagraha began on March 30, 1924 when volunteers approached the police barricades and sat down in front of them. They were prevented from going further, arrested and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment. In less than a month the principal leaders were behind bars and the campaign was lacking direction or any kind of strategy beyond attempting to convert the orthodox Brahmins through voluntary self-suffering. But as one of the leaders, K.P. Kesava Menon, commented, “We were under the impression that they [the Brahmins] could be won over by satyagraha. On the contrary they turned more bitter and ireful than before.” After April 10 the campaigners no longer benefited from the drama and publicity that attended arrests and imprisonments, as the British police commissioner, W.H. Pitt, ordered these to stop. The monsoon rains that began in April were unusually severe and by June there was extensive flooding. Despite this, the volunteers maintained their vigil, sometimes standing for hours at a time up to their necks in water. One volunteer died. The satyagrahis also faced counter-demonstrations, some of them violent, by orthodox Hindus wanting to put an end to the campaign.

The first hint of change came in August when the incumbent — and rigidly orthodox — Maharaja Thirunal died and was replaced by the more open-minded Regent Maharani Bayi. One of her first moves was to order the release of 56 prisoners, among them 20 of the imprisoned Vykom satyagrahis, including T.K. Madhavan, Kesava Menon and other leaders. In October, following an earlier suggestion by Gandhi, two giant processions of caste Hindus, including Namburis and Nairs, set off for the state capital, Trivandrum, from Vykom in the North, and Kothar in the South, with a petition bearing 25,000 signatures of caste Hindus. This requested the Maharani to command “that all roads and public institutions without reservation be thrown open to all classes of … subjects without distinction of caste or creed,” and affirmed that Savarna Hindus “are willing to co-operate with the government in removing the disabilities of our Avarna Hindu brethren.”

Meanwhile, in early October, an Ezhava leader, N. Kumaran, general secretary of the SNDP Yogam and a member of the Travancore Legislative Council, had introduced a resolution calling for the opening-up of every Vykom temple road to all castes. King cites part of a speech by the Dewan (who functioned effectively as Prime Minister on behalf of the Maharaja as head of state) adamantly opposing the resolution, which shows how little effect the attempts of the satyagrahis to soften the hearts of their opponents was having. When it finally came to a vote in February 1925, the resolution was defeated by 21 votes to 22, due to the fact that the government bloc voted against it.

In March 1925, Gandhi visited Vykom as a state guest. At a three-hour meeting with senior temple guardians he encountered first-hand their intransigence and determination to hang on to their privileges. He made three offers: a one-day referendum of all upper-caste orthodox Hindus on opening the temple roads, either in the Vykom district or the whole of Travancore; arbitration on the issue of unapproachabiltiy by pandits (Brahminical scholars of Hindu scripture, law and rituals) chosen by both parties, or a decision by acknowledged pandits. King comments that this last offer “inadvertently legitimized the supremacy of the Brahmins’ own ideological interpretation of their preeminence and grandeur” and ignored reform movements based on unwritten religious precepts other than the Brahminical, such as that led by Narayana Guru. Nevertheless the temple guardians rejected all three options.

In the following days Gandhi held discussions with the Maharani Regent, with Narayana Guru, and the Dewan. Significantly, at a public meeting in Trivandrum on March 13 he spoke of “compelling by pressure of public opinion” the acceptance of one of the three options, or better still “the opening of these roads to the untouchables and unapproachables.”

During the state visit he was accompanied by British Police Commissioner W.H. Pitt and in the course of their discussions they came up with a compromise plan, which was accepted by the Travancore government. Under its terms, the legal prohibition on the use of the eastern road nearest the temple would be lifted and the barricades removed on the understanding that the satyagrahis would not attempt to enter that part of the road, but would mount small pickets at its limits where the barricades had been.

The satyagraha in this token form, continued until November 23 when a new compromise agreement came into effect. Its exact terms, King discovered, are still unclear. No formal document recording it exists in the state archives. What emerged, however, was that the roads encircling the temple were open to all except the one on the eastern side, which was reserved solely for the use of caste Hindus, and open only when a service was taking place. It continued to be closed to Dalits, but was now also out of bounds to Christians, Jews, Sikhs and Muslims who had previously been allowed to access it. As a concession, however, the government had a new bypass road built on the eastern side open to everyone regardless of caste or religion. It was a feeble compromise which meant that after everything the campaigners had endured, the situation had changed little, and the right of the Nambudiri temple authorities to bar Dalits from temple roads was confirmed rather than undermined. Several of the prominent leaders of the campaign from the avarna community were highly critical of the deal; one of them, E.V. Naiker, resigned from the Indian National Congress the day after the Vykom satygraha ended and called the settlement a betrayal. King describes it as “an artful expedient, indeed legerdemain.”

King is an admirer of Gandhi and recognizes his historic importance in developing a method of struggle without violence. She also argues that without the involvement of Gandhi and the patronage of the Indian National Congress, the Vykom satyagraha would have been “diminished to a merely local, if not unheard-of event in the history of modern India.” But she is critical of the strategy upon which Gandhi insisted, namely that of converting the temple guardians through the voluntary suffering of the satyagrahis. This led to mistakes such as the decision of all the main leaders to court arrest and imprisonment at an early stage, leaving the campaign adrift and the volunteers with no leadership or alternative strategy. She also argues that Gandhi failed to understand that organizing by untouchable communities was ultimately as important as the attitudes of the orthodox. Most of the avarna community in Travancore did not engage actively in the struggle and Narayana Guru strongly disagreed with aspects of Gandhi’s strategy.

The overly-optimistic interpretation of the campaign’s outcome has, King argues, sometimes affected the thinking and strategy adopted since by nonviolent campaigners elsewhere and has resulted in unnecessary suffering. It could also lead, she argues, to the acceptance of intolerable oppression on the grounds that the opponent has not yet been “converted.” Fortunately, scholars in the field, notably George Lakey and Gene Sharp, have relegated conversion to a more minor and infrequent explanation of how nonviolence succeeds, and shifted the emphasis to the political and social pressures that can undermine the opponent’s authority and legitimacy. King cites a 1952 article by the Gandhian socialist, Rammonohar Lohia, in which he expresses despair at hearing about melting the hearts of the oppressor; instead he wanted to hear about the hearts of the oppressed, “so that they can rise up to help themselves.” In short, the crucial thing for Lohia was that the oppressed should become more fully aware of the injustices they suffered and take concerted action to end them.

The sociological mechanisms of nonviolent change as originally listed by Lakey in his 1962 Master’s thesis, and modified by Sharp, are conversion, accommodation, nonviolent coercion and disintegration. Conversion is relatively rare though often accorded preeminence in the early literature; accommodation occurs where the opponent, sensing that power is slipping away, is prepared to accede to at least some of the challengers’ demands and adjust to a changed situation; nonviolent coercion occurs where the power balance has shifted so far that the opponent has no choice but to agree to the demands; disintegration implies that the opponent as a political or social entity has ceased to exist. In Travancore, unlike in his major national campaigns, Gandhi advised the campaigners to rely on conversion as the means to achieve their goals.

One further point, however, needs to be made about conversion. The principal opponents of an emancipatory campaign, hardened by ideology or the desire to hold on to their privileges, may be largely immune to reasoned argument or the emotional and moral appeal of people persisting in nonviolent action despite hardship, suffering and risk of injury or death. But this is not necessarily the case with the various groups and sections of society which form what Gene Sharp calls the “pillars of support” of any government or power structure. Sympathizers of the campaign may be “converted” into activists and others formerly indifferent to it — or third parties not directly involved — may shift their position to provide support at various levels, or at least withdraw even passive support for the opponent. It seems reasonable to suppose, for example, that among the 25,000 caste Hindus who signed the petition to the Maharani in October 1924, many would have been moved to act by the perseverance and nonviolent demeanor of the campaigners.

Gandhi’s dilemma in the Vykom campaign was that while he wanted to abolish untouchability, he also wanted to include all Hindus in the national struggle. As King observes, he “wanted to avoid flagrant political confrontation and civil disobedience against the traditional ruler of an Indian state,” hence his emphasis on persuasion and conversion in the context of that struggle. He opposed turning the Vykom satyagraha into a national campaign and insisted that he did not regard it as part of the wider noncooperation movement. He actively discouraged the participation of non-Hindus in the campaign, taking the view that a Hindu’s silent suffering would be more effective than legions of non-Hindus. He even called for the closure of a field kitchen set up in the vicinity by Akalis (members of a reform Sikh association), who had traveled hundreds of miles to be there to provide sustenance for the volunteers. He regarded the Vykom campaign as “a socio-religious movement” with “no immediate or ulterior political motive behind it.” This contrasted with the view of some of the Ezhava leaders that it was a struggle for the recognition of the basic civic rights of all citizens.

As regards the wider effects of the Vykom campaign, King notes that, despite its limited and ambiguous success, it inspired and stimulated social movements elsewhere in India, and contributed to the groundswell of opposition to untouchability. However, in the short-term there was no domino effect of temple-roads and temples being thrown open. In Travancore, the government ordered the temple roads across the state to be open to avarnas in 1928, but it did not end the restrictions on temple entry until 1936, some 12 years after the end of the campaign. And universal temple entry across India did not occur until independence in 1947.

Despite her criticisms of Gandhi’s strategy, King argues that his interest and commitment is revealed to have “played a crucial role, regardless of the shortcomings of some of his actions and ideas.” King’s clinical assessment of Gandhi’s strengths and weaknesses enhances rather than diminishes his stature by stripping it of the uncritical veneration of the “Mahatma” in many accounts and locating his achievements in the political and social context of the period. Her book is essential reading for anyone interested in the theory and historical development of nonviolent action.

Many thanks to Mary Elizabeth King for getting to the bottom of this conversion business, and to Michael for letting us know via this column! Two comments: one on conversion and one on Gandhi’s macro-strategy.

Regarding conversion, although I was impressed sufficiently by the misrepresented Vykom campaign in writing my MA thesis to give a mechanism that name, and to develop some theory to account for the possibility of converting our opponents, I couldn’t find other clear examples in which that happened. Fast-forward to now, when we have the Global Nonviolent Action Database with its 1000-plus cases. Last year I looked widely among the cases there hoping to find a batch of conversion cases, and I could find only one that seemed really clear-cut. I conclude we’re warranted in assuming that conversion is far less likely to happen than persuasion/accomodation or coercion.

Regarding Gandhi’s big picture, I see his choices as revealed in the column as consistent with his deferring class struggle also until after Independence. It’s a natural choice among leaders of independence struggles: do what you can to unite as much of the population as possible by focusing on the central struggle, and leave other important issues (like equality and economic justice) to be tackled when self-government has been achieved. To me, a reasonable choice, and at the same time bound to be painful for those who live with continued oppression (caste, gender, sexual orientation, class, and so many others) while focusing on the one big struggle that is intended to put us in charge of our own house. I’ve heard that Gandhi wanted to live well beyond 100 years so he could personally lead many equality struggles, and that was one reason he chose not to become leader of the state (think Mao, Lenin, Washington, Nkrumah, et al) that was founded thanks to the struggle he led. Remarkable innovator, Gandhi. But what painful choices await all of us who take responsibility for change in a society that is sunk deep in multiple oppressions! Passionate comrades will disagree about what choices to make. I don’t see anything simple about it, even in retrospect. A good time to remember, in our own 2015 context, that political/strategic disagreement is to be expected in the course of things, and we can respect each other even through the times we differ.

Again, many thanks to both of you!

George

South India or south India?

During his 30 years of work (1917–1947) for the independence of his country from the British Raj, Gandhi led dozens of nonviolent campaigns, spent over seven years in prison, and fasted nearly to the death on several occasions to obtain British compliance with a demand or to stop inter-communal violence. His efforts helped lead India to independence in 1947, and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom worldwide.

By the way! The best essay writing service – https://www.easyessay.pro/

And Happy New Year!