What does an article he wrote for his college paper mean for a president’s policies in office?

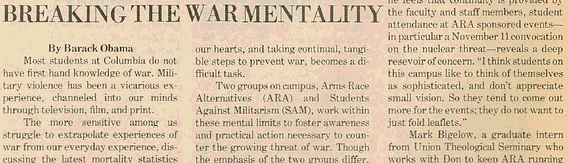

On the front page of today’s New York Times, William J. Broad and David E. Sanger report on Barack Obama’s past and present interest in nuclear arms reduction. It centers on a 1983 article he wrote for Columbia University’s magazine Sundial in which he profiles a pair of anti-nuclear-weapons groups then active on campus and laments “the relentless, often silent spread of militarism in the country.” In those days, he recognized that the nuclear freeze many activists called for in response to Reagan’s monstrous buildup wouldn’t be enough; outright reduction, he believed, was necessary.

By all appearances, a quarter-century later, Obama hasn’t grown out of his college-age instincts. On the campaign trail and in office, he has spoken repeatedly of hope for “a world without nuclear weapons” and proposed initiatives to bring it about, including ratifying the comprehensive test-ban treaty and negotiating a new treaty to ban the production of fissile material. Earlier this year, he overruled Secretary of Defense Robert Gates’s effort to secure funding for a new generation of nuclear warheads.

Predictably, nuclear reduction isn’t an easy task, politically. The usual suspects on the Right have voiced concern ever since the Columbia article surfaced late last year on the internet. Nevertheless, respected Republicans like Henry Kissenger and George Schultz—Reagan’s secretary of state—have raised their voices in favor of reduction. Lately, Obama has framed the cause for reduction mainly in terms of diplomatic efforts to keep nukes out of the hands of Iran and South Korea. While this argument has some sense to it, as well as the benefit of bipartisan urgency, it runs the risk of reducing arms control to mere tactics, jeapordizing the whole effort if, in these cases, it doesn’t work. Ridding ourselves of our biggest guns will require a whole lot more willpower than the desire to beat out a rougue state; many, many more of us will have to come to realize that we don’t want them anyway.

For those of us working to bring an end to our government’s apparently boundless faith in the efficacy of violence, Broad and Sanger’s article is encouraging. But it does raise questions about how fully Obama understands the “often silent spread of militarism in the country,” which continues under his watch. We’re still fighting two raging wars abroad and devoting enormous resources to do so. As American manufacturers lose their business arrangements with the automobile industry because of the recession, there is a real danger that more and more of them will turn to making weapons. At present, there’s no industry so dependable than war. More of our factories, workers, and communities will depend on vast military expenditures, and politicians will feel pressure to provide the wars to fuel them.

The young Obama was right about nuclear weapons: freezes aren’t enough. We’ve gone too far already, and it is long past time for reduction. We have to remind him now that nukes are only part of the problem, and that we’ll stand behind efforts he makes to find true, lasting solutions.