Twenty-five years ago, fierce winds of resistance were blowing against autocratic communist regimes around the world. Tank man stood in Tiananmen Square; the Solidarity trade union was legalized in Poland; the Berlin Wall came down in Germany; the Velvet Revolution overthrew the Communist Czech government; and a 156-foot-long gaff-rigged schooner departed New York City bound for Leningrad on a historic Soviet American voyage for the environment.

Perhaps the Soviet-American Sail 1989 didn’t make headline news on par with the other historic events unfolding at that time, but it sailed on the same winds of change. As part of the tidal wave of citizen diplomacy, it helped fuel worldwide struggles for democracy, international environmental work, and an end to the Cold War and nuclear arms race. The Iron Curtain’s first crack showed up in the spring of 1989 when Hungary took down 150 miles of barbed-wire fencing on its Austrian border. By the end of 1991, every communist country had held contested elections for the first time in decades, signaling the general collapse of autocratic communism and the dissolution of the Soviet empire.

As I look back at the Soviet-American Sail and my role as coordinator of this epic voyage, I am washed over with the sense that there may be some valuable learnings for today. Certainly it floods me with amazement that we pulled it off — that a few sailors and environmentalists managed to bring together a wildly disparate crew and safely navigate oceans of misunderstandings, proof that on some level enmity and distrust can be overcome.

What bold ventures could be harnessed to address the pressing issues now — climate change, economic injustice, civil war?

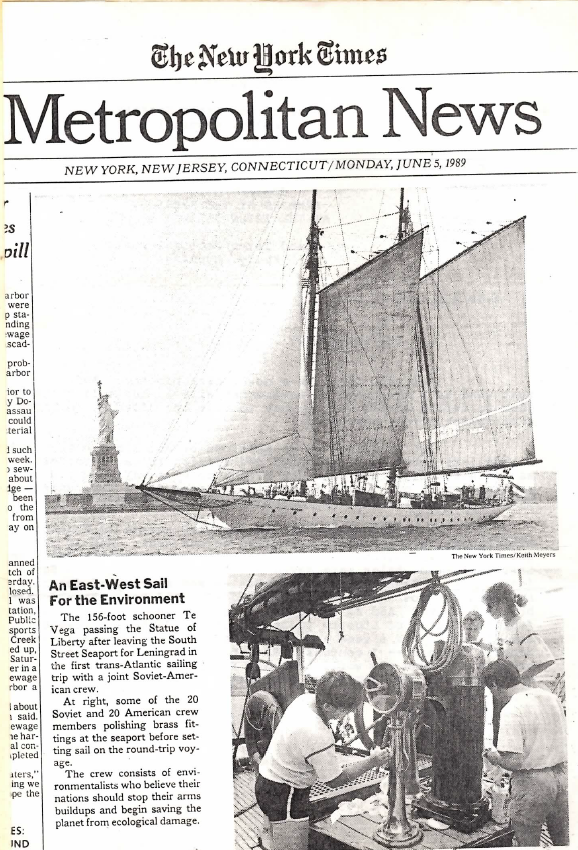

I was fortunate to be on board the S/V Te Vega as she departed South Street Seaport in New York City with the first leg of 45 Soviet and American crew members to a wildly enthusiastic crowd of supporters on June 4, 1989. There was a plane that wrote “Bon Voyage” in the sky over the harbor, a high school drum corps on the dock, tall ship escorts to the Verrazano Bridge and New York City fireboats with water canon spray. In March, the New York Times published a full-page article about the upcoming venture, and promised a follow-up story — which was reduced to a photo and a short quote because of Tiananmen Square and the Solidarity election stories of the day.

I was fortunate to be on board the S/V Te Vega as she departed South Street Seaport in New York City with the first leg of 45 Soviet and American crew members to a wildly enthusiastic crowd of supporters on June 4, 1989. There was a plane that wrote “Bon Voyage” in the sky over the harbor, a high school drum corps on the dock, tall ship escorts to the Verrazano Bridge and New York City fireboats with water canon spray. In March, the New York Times published a full-page article about the upcoming venture, and promised a follow-up story — which was reduced to a photo and a short quote because of Tiananmen Square and the Solidarity election stories of the day.

Although this was the third Soviet-American citizen diplomatic venture I had taken part in, it was my first as director and organizer. The seed for this sail was planted in Leningrad in 1987, on the first night of the historic Soviet-American Walk. My dinner partner that night was Gregori Temkin, a science fiction writer and co-founder of Travels for Peace and Environment, one of the blossoming environmental groups springing up under the nascent glasnost and perestroika of the Gorbachev era. In short order we realized we shared a background in environmental work focused on water and ridding the world of the insanity and waste of nuclear weapons, along with a love of sailing. Serendipitously, Travels for Peace and Environment was destined to be our Soviet counterpart.

Sometime in the following cool fall season aboard the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater where I was chief mate, our hot idea was hatched. Skipper Albert Nejmeh and I realized that as environmentalists and activists we wanted to address the ignorance that fueled the U.S. and Soviet fear of each other and was used to justify the Cold War. As sailors, it seemed natural for us to propose a sail and chart our own course in the radical political waters of 1989.

On our days off we set about trying to secure a Soviet partner, a boat large enough to accommodate a good sized crew and support of all kinds. Immediately I wrote to Gregori, but it was many air-mail letters and several anxious months before we actually established contact and reciprocal interest. The Clearwater community fell in behind with more than we could have dreamed up: office space, fundraising and media support, crew members, volunteers and supplies.

“We’re All in the Same Boat” was the slogan that summed up the reasons behind our willingness to work to make this real. We knew any healthy and peaceful future rested on our ability to overcome our divisions and work together. Our oceans can be viewed as bodies of water that separate us, but they are also what connects us, and throwing Soviets and Americans into a situation where working together would be necessary to be successful would amplify our interdependency while modeling solutions.

It was a phenomenal one-and-a-half year effort to turn the sail from idea into reality. For me personally, as a chief instigator and full-time coordinator and only in my 20s, there was an extremely steep learning curve. Everything from bi-national negotiations to visa applications, program development to staff selection, legal contracts to budget oversight, and on-board scientific research to cross-cultural education seminars had to be worked out.

In spite of naiveté and limited resources — or because of it — we did a lot of things in a way that built local capacity, engaged broadly diverse groups of people and spread the message widely. Sharing both the opportunity to participate in and the responsibilities of organizing and funding out to participants moved us to invest in capacity building — helping each participant provide leadership so that our political leaders could follow.

We spoke from our hearts and our personal knowledge as who we were: sailors, students, folksingers, scientists, grandparents, videographers, cooks, scholars, entrepreneurs. The youngest was three, the oldest, one of our translators, was 73. We were male and female, some multilingual, some professional sailors, all committed to the project. We developed a “party line” and talking points about our voyage to help with media and outreach, but encouraged everyone to adapt the rap to their own personal situation.

The Soviet-American Sail 1989 was funded in two ways: by general donations and by crew donations and work. Professional boat crew donated their time; U.S. participants each raised $3,500 from their local communities to participate. Often, this was in exchange for promising to do a community presentation on the trip after returning, which both succeeded in raising money and building an invested grassroots following our project. Since $3,500 was equivalent to a yearly salary for the average Soviet participant, Travels for Peace and Environment secured a grant to cover the costs for their crew. In the United States, our tight-wire budget was won in increments of $5 and $10, with our four largest donations being $1,000 each.

We emphasized local media connections along with national networks — again to work the grassroots educational aspect. Almost every participant had stories in their hometown press or endorsements from their hometown politicians and leaders.

Local connections were taken one step further — in both the United States and the USSR, Friendship Tours happened for a week before and after the transatlantic sails. All the American and Soviet crew visited communities along the eastern U.S. seaboard from Washington, D.C., to Maine, and from Leningrad to Moscow. The crew was hosted by local families, visited schools, held public events, met with local media and generally were available in the communities. As international sailors and researchers, we were welcomed at old guard yacht clubs as well as peace centers, VFWs, cultural clubs and scientific centers. There was an amazing outpouring of hospitality and hunger to meet the “other.”

As a sailor who had studied marine ecology and worked on educational research vessels, it was critical to me that we use Te Vega’s platform in service of scientific research to contribute towards understanding environmental issues — specifically on plastic in the Atlantic, acidity of precipitation, chlorophyll production and sealife monitoring. Plastic was found in 33 out of 34 samples taken on the first leg of the sail. The results were added to, and published as part of, ongoing research efforts at the Sea Education Association, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Millbrook Ecosystem Center.

On board seminars were successful as well — with the opportunity and encouragement for each participant to present a topic of their own choice, along with ongoing language, scientific and cultural sessions. Sharing the stage, as it were, was another physical embodiment of our commitment to learning from each other.

Of course, it was not all smooth sailing. The biggest sticking point of this revolved around food, where our cultural practices manifest daily. In brief, the Americans on the crew were more likely to be “hippies:” somewhat health conscious, interested in low-fat, generally vegetarian, low-sugar diets while the Soviets were less likely to care about the health aspects of food, and believed that meat, fat and starches were essential elements of any “worthwhile” meal. On the trip over to Leningrad, which was stocked by the United States, the meals were in line with the American interests, while on the return trip, provisioned by the Soviets, an entire side of a bloody cow was loaded onto the ship.

Communication was a constant challenge, and translators on board did much to facilitate a transition so that by the end of the travels most people were able to communicate effectively in one way or another. Cultural issues did present challenges — specifically, some need for decision-making prompted the Soviets to insist, stereotypically, on simply designating a few representatives to lead and make decisions on behalf of everyone, while the Americans insisted that each person have a vote.

As co-creator and director of the Soviet-American Sail 1989, it was an incredible gift to be able to use our own expertise, to follow our own navigational star in designing and executing a creative pathway to alternative solutions, and to model cooperative efforts to take on seemingly entrenched political and environmental problems. The sail established new horizons for citizen diplomatic ventures: It’s likely the first time environmentalists from the United States and the USSR made such an ambitious Atlantic crossing, as well as the first joint plastics research to take place.

The Soviet-American Sail 1989 highlighted the necessities and benefits of facing challenges together and the potential of learning from each other and harnessing each other’s differences to help solve our problems. Twenty-five years later, we’re still in the same boat — and that boat is worse for the wear and tear of the last couple of decades. What is 2015’s venture?

Excellent story . Is the Te Vega still around? We are going to need it.

Very funny, Bill !…

I think she is currently owned ( according to Wikipedia…!) by Italian fashion magnate Diego Della Valle (Tod’s et al.)

It was a great ship for our journey, though on the outbound leg about a week out from NY City we hit a storm ( and rollicking storm swell.) The old rig took a bashing:: a spreader busted, unbalanced the rig causing a gaff to break, the fore’s’l then shredded, and more! We limped about 300 miles due north into Lunenburg, Nova Scotia for repairs. Luckily, it is the home of the Canadian ambassador schooner Bluenose, and the shipyard had an old spar we could use to replace the gaff. I spent the week bent over the old sails stitching away in the North Sails loft. As coordinator at the time, i was worried that was the end of the SAS, but back to sea we went…whew!

Hi Nadine, My fellow Sloop Singer

Dan Einbender who I also knew from back in the early 70’s Coffee house at Northwestern University Asked me to put on a Benefit Concert in support of the Soviet American Peace Sail down here in Florida. It was a great tribute to American Folk music at the Unitarian Church of Clearwater July 15th of 89. I saved the poster and I shared the stage with Bill Bullard, Al Gore, Harpbeat, Richard Leps, Becky Palmer, and Susan Street. Pete’s Gang now is growing in Florida and hope you can join us sometime.

Nadine,

What an inspiring story. Had no idea you did this. Which I could have been part of that history making adventure although I can’t swim for my life. Next frontier is a solar powered air balloon from US to Russia to track global warming!

Love this idea..!

Also, as I write this there is another voyage underway to challenge the Gaza blockade and end violence in the region. See this for more info: http://www.gazaark.org/2014/07/28/planning-to-launch-new-freedom-flotilla-to-challenge-blockade/