The legacy of the brutal Burmese regime that kept glamorous challenger Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest and its tightly controlled society closed off to outside influences had seemed poised for real change. Just a month ago, as the early sunlight spread across the Bagan plain lighting up hundreds of ancient pagodas and warming up a sizable gaggle of tourists (including myself) perched high on one of the structures to witness the sunrise, it seemed clear that a new day was dawning.

As part of the inaugural Beautiful Rising workshop, we had gathered in Yangon the week before to hear stories of resistance and begin to tease out the shared lessons that these events held for frontline activists. Exploring activism under a repressive regime might not be where you would start looking for creative case studies, but, in fact, that is often where creative cultural resistance can be both the most impactful and least risky option. Of course, brutal crackdowns on activists can, and do, silence dissent in that moment — but they won’t encourage loyalty or increase the legitimacy of the ruling power. In fact, it is often just the opposite. Effective resistance post-violent repression generally looks more creative, more subversive, more underground and more dispersed. Paradoxically, it can also cut where no knife has an edge, fueling the courage to resist, spreading the movement, and culturally hammering the power holders.

Even five years ago, it would have been hard to imagine a Beautiful Rising gathering taking place in Myanmar at all. In 1962, a military coup abolished civil and political organizations and outlawed gatherings of more than five people. For those who follow regime changes around the world, Myanmar’s transition from 49 years of a brutal junta to a quasi-civilian government in 2011 was cause for cautious optimism in most of the country. The last four years have seen further baby steps in a positive direction, with elections planned for this fall and official censorship eased. The student protests are some of the signs that the muted civil society had once again, somewhat cautiously, begun exercising its voice.

As our workshop developed, news of the students marching towards Yangon energized the room. The students are organized, determined and social media savvy. Facebook memes capture their rallying cries of, “We are students not customers,” with a logo showing students pushing an earth off of its barcode pedestal. In another, a fist clutches a pen in echoes of Occupy or Otpor in Serbia. Historically, students and monks have been the leading edge pushing for change in Burma, with a starring role in the nationwide pro-democracy protests in 1988. In January, the students began marching towards Yangon — following in the tactical footsteps of many before them, and reflecting other marches also ongoing in Myanmar.

Strategically, the students chose this path to put educational issues into the public discourse, as well as use and garner participation from those on the sidelines. The parents and elders who showed up along the road have offered some protection from violence by being witnesses, and are also a skin-and-bones reminder to the government that the country sides with the students. This flood of public support pressured the government to meet with the students in early February, during which time the students suspended the march awaiting the outcome of the talks.

A few weeks ago the government agreed in principle to honor all 11 demands of the student groups; however, the students kept marching, rightly fearing that without continued pressure the parliament would not follow through. In fact, the uncertainty continued with delays in meetings, increasing threats of retaliation from the authorities if the march continued, and disingenuous attempts to split the student activist groups. Yesterday Myanmar police beat students, monks and journalists in a crackdown on the two-month-old march for a new democratic education law, damaging bodies along with the facade of civil government control.

Yesterday’s violence leaves the outcome of the student protests in flux right now, as is the immediate future of Burmese civil society. When we met with the students a month ago, they clearly articulated a fear of being brutally shut down if their demands for educational reform were conflated with calls for regime change, hoping that limiting their protest to the education sector would extend their ability to demonstrate. Their goal was to maintain nonviolent discipline, unity and focus in order to continue their education activism without severe repression to avoid increased support for the ruling party and derailing the upcoming civil elections.

A month ago, the students were looking for new tactics to increase the pressure on the government to do the right thing and avoid a crackdown. Today, this is more urgent, and luckily there are fabulous and courageous examples of creative cultural resistance from within Myanmar — in spite, or possibly because of, the severe limitations imposed by the regime. It is worth a look at a handful of these creative actions not only for the sheer compelling nature of the events, but also to tease out the critical lessons that they might hold for the students and others who follow them.

1. Seizing the moral high ground

As an activist, if you can seize the moral high ground while waging a campaign, you are not only talking the talk, but also walking the walk. Harnessing cultural rituals and symbols only increases your legitimacy and potential for leadership in the conflict. This has been critical in the overwhelmingly Buddhist Myanmar, as Buddhist monks traditionally anchor the moral and ethical compass of the country. They have been royal advisers and guides to political enlightenment, and serve as guardians of the sacred rights and responsibilities of the people. Most famously, the “The Golden Uprising,” as it was known in Burmese — or the Saffron Revolution in English — was led by the All Burma Monks’ Alliance, which took a stand in order to serve the people and resist suffering imposed by the regime.

In particular, two religious traditions were used to call out the military junta for egregiously violating the teachings of the Buddha. First of all, public chanting of prayers by monks was intentionally done in sympathy with the suffering public. Monks were brutally beaten by the regime for this act of defiant solidarity.

Second, and perhaps even more famously, the monk’s coordinated act of “overturning alms bowls” exemplified the power of using cultural ritual in activist communications. Every day it is the Buddhist monk’s tradition to walk around the community to collect alms from lay members; in 1990 and 2007 monks physically refused to take donations from military men and their families. This simple act of refusal, which effectively denied the authorities the ability to gain religious merit, one of the main daily Buddhist practices, delivered a severe moral and political challenge to the ruling regime.

Since both the government and the majority of the country is Buddhist, using the religious rituals spoke directly and powerfully to them. As well, the public chanting and turning the alms bowls upside down were easy to do because they were already “tools” that the monks had at the ready — no need to purchase or create something new.

2. Using prejudices to your advantage

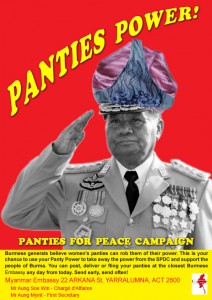

If you are a group of generals who believes that touching a woman’s undergarments (clean or dirty) could sap you of your “power,” you probably are setting yourself up for a problem. In fact, in 2007 a group called the Lanna Action for Burma Committee in Thailand organized a “Panties for Peace” action, asking women all over the world who cared about Myanmar to send underwear to the Burmese generals via international embassies. As the website read: “This is your chance to use your Panty Power to take away the power from the SPDC. You can post, deliver or fling your panties at the closest Burmese Embassy any day from today. Send early, send often.”

Hundreds of pairs of underwear were reportedly sent to embassies as an intimate, but not insignificant, insult. Panty Power was a humorous way to show serious support for the pro-democracy protesters and fluster the regime with lace, flipping the tables on sexism and using the junta’s prejudice against them. During a time when public gatherings were outlawed, it offered an easy and low-risk way to participate on one’s own schedule. It brilliantly used a superstition and cultural taboo to confront immense power and inject humor into a dire situation.

Another humorous assault on the regime was launched at about the same time. Anonymous activists attached pictures of the regime leadership to the collars of stray dogs. (Mind you, it is a very serious insult to relate anyone to a stray dog in Myanmar.) The authorities were driven mad trying to catch the evasive protesting animals with general’s pictures dangling from their necks in various townships around the country and brought moments of laughter to observers. There is nothing like a stray dog sporting a general’s photo to breakdown a spell of power.

3. Fighting hate speech with flower speech

In a country that has experienced widespread ethnic strife, one would hope the transition from military junta to nominally civilian government in 2011 would have had a positive impact. Not so much in Myanmar — there is still much conflict between the majority Buddhist population and the minority Muslim population, particularly focused in the state of Rakhine.

With the opening up of the country came exponential growth in access to, and use of, the Internet — with all of its benefits and baggage. It is predicted that access to the Internet and mobile phones in Myanmar will go from 10 percent in 2013 (one of the lowest rates in the world) to 50 percent by the end 2015. And of course the Internet is monitored by the state — in fact, until 2011 every publication in the country was censored before printing — and although there has been some relaxation in that policy, the government has made it clear that they are monitoring the web.

Over the last couple of years, there has been widespread abuse by extremist groups spreading misinformation and calls to violence — particularly from Buddhist extremists inciting rage against the Muslim Royhinga minority. Facebook posts (from nationalist Buddhist monks no less) have led to mob riots and deaths and a government shut down of the site in an attempt to limit the violence. Pro-democracy activists are concerned about the sectarian violence, and this censorship.

In April of 2014, Nay Phone Latt, a well-known blogger and head of Myanmar ICT for Development Organization, who was previously imprisoned for four years for his anti-government writings, started an online campaign to fight hate speech with “flower speech.” They encouraged people to post photos of themselves with yellow Padauk flowers in their mouths. As Myanmar’s adored national flower, they traditionally represent strength and honesty. It is a campaign using Facebook posts, stickers, posters, T-shirts, wristbands and songs in an attempt to combat the spread of “dangerous speech” and inter-ethnic tensions, and to convince people to embrace Burma’s diversity. “Our slogan is to be careful, not to be silent,” Nay Phone Latt said. “We just got freedom of expression, and we don’t want to be silenced.”

There are some great lessons to pull out of the #FlowerSpeech campaign as it has captivated not only Myanmar but other countries. An active presence on social media sites coupled with physical events, music and stickers has helped spread the word of a blooming movement dedicated to responsible speech — there were many easy entry points to become part of the campaign, online and off. It didn’t hurt that the Buddhist culture already embraces a code of ethical conduct that includes a tenant of “Right Speech” — to avoid abusive, divisive or harmful speech. And the use of the already important cultural element — the Padauk flowers — meant a familiarity with the images and an immediate comprehension of the message. An activist told us that the first graphics developed for the campaign had to be changed. They looked more generically Asian and didn’t resonate directly with Burmese. The next images were intentionally crafted to more accurately reflect Burmese culture and dress to increase local appeal.

Anytime you can base a campaign on relatively non-controversial asks — like using non-hateful speech — it makes it easier to reach a broad audience. While hate speech isn’t physical violence, it certainly can incite and even normalize it, so efforts to counteract extremist language are useful on that spectrum and remind others that they are not alone in opposing hatred. #FlowerSpeech is a welcome bloom on the path to an equitable and fair Myanmar.

4. Laughing in the face of repression

Everyone knows that one of the best ways to get away with criticism is to make a scene, embed it in comedy, or shroud it in colorful garb. In Myanmar, a long standing comedic trio called the “Moustache Brothers” offered all this and more. What started as a way for locals to escape from the difficult repressive reality of hard life in Myanmar continues today as a way to communicate with the international community and poke at the government to support change.

Originally a group of two brothers and their cousin, they performed a-nyeint pwe — a traditional Burmese vaudeville that includes wacky slapstick, classic women’s dances, canned music and political satire. Even though audiences were laughing, the regime wanted none of it, and jailed two of the brothers for seven years of hard labor in 1996 following a performance for Aung San Suu Kyi. (Supposedly, the trio drew lots to see who would get to say the most risky lines.) As part of their early release agreement, they were banned from performing their work in public, or for a Burmese audience.

So today if you venture to Mandalay, Myanmar’s second largest city, you can catch the show any night of the week at the Moustache Brother’s home. On the ground floor they have fashioned a small performance space where a storefront would have fit. Although taxi drivers no longer seem as afraid to drop off people to see the show as they were before, it is only foreigners who attend, as the ban still stands.

One of the brothers, Par Par Lay, died in 2013, but only after launching a “No Fear Campaign” that he toured around Myanmar in a pitch to urge people to abandon their fear of politics. He served time for this work as well. Lu Zaw and Lu Maw continue the shows as a duo. There is always a lot to learn from a group like this who has persevered for so long, harnessing their art form and cultural heritage to lighten the load for locals, build support from the international community, and speak truth to power every night of the week.

Laughing, flowers, panties and seizing the high moral. I love that combination.

Thanks for a great article with some very compelling and funny ideas of actions.

It was exciting to see the junta back off and allow some democracy and then distressing to see some use that opening to attack other ethnic groups. It’s a reminder that life is complicated and requires good organizing.

artistic/cultural jujitsu – turning the opponents’ shibboleths against them – is powerful

Perseverance in the face of long term brutal repression is difficult, commendable and necessary in many circumstances. The strength to stand up and perform every night, seeding humor in a grim situation, facing your fears and casting for shreds of hope — personally mind boggling. In that vein, here’s a few bits shared by the Moustache Brothers when I was in the audience in Feb, 2015:

“So I went across the border to Thailand to get some dental work done. The dentist said, you must have dentists in Myanmar? I said, Of course we do, but we’re not allowed to open our mouths!”

“Be careful while here– Don’t steal anything, the government doesn’t like competition”

“You tourists are our Trojan Horses– through tourists the rest of the world can learn of our plight.”

Thanks for a great article.

If you get this far to the comments, please take a moment and support the student activists. Here is their call:

Please Just Give 3min! Your Photo Message Can Be A Change!!!

# Write your short and strong message on piece of paper for Myanmar Students

#use the hashtag on your paper: #wearemmstudents

# Take Photo with you and the paper

# Send to

https://www.facebook.com/pages/We-Support-Myanmar-Students/1617301761814639?ref=tn_tnmn

(Or) you can post on your Facebook by embed

#wearemmstudents

In March 10, Myanmar students for National Education Reform were brutally violated by Myanmar Police in Lepandan. 127 protesters including students, monks and other people are arrested. Students are asking for National Education Reform, passed by Parliament in Sept 2014 without having transparency through public consultation, endangers the academic freedom and centralized power over the education system that leads the improper national budget allocation for education.

Please invite to all your friends to stand up for Myanmar Students and National Education Reform

Your article makes me think of spring, with brutal oppression as winter while the seeds of creative resistance grew and commingled their roots — a great story of hope!

Wonderful article, Nadine!

Arts and activism were widely harnessed in various Latin American countries. It’s great, as a Cambodian, I can learn from Burmese. We are facing more of the same military dictatorship. We haven’t found a way out of fear into collective actions yet. The arts are controlled and artists self-censored out of fear. We praise the Burmese people. A truly free Myanmar will trigger down to us, and I hope we can find the courage just as the Burmese had in their fight for freedom and justic.

Just wanted to add a note about the Burmese artist activist who just won one of the prestigious 2015 Goldman Environmental Awards,Myint Zaw. He launched a national movement that successfully stopped construction of the Myitsone Dam on Myanmar’s treasured Irrawaddy River. http://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/myint-zaw/

As a way to get around the Regime’s severe limitations on public gatherings,he began organizing art exhibits—a strategic choice, given that galleries were among the few spaces where he could engage activists, scholars, artists and citizens while avoiding government scrutiny. The series of art exhibits turned into a national advocacy movement, with people taking their own initiative to bring awareness to the issue. Artists began writing poems and songs about the river. Citizens spread pamphlets and DVDs about the dam in their own communities.

The growing movement attracted the attention of newly elected parliament members and local media, whose ability to cover social issues was gaining some breathing room since the new government in 2011.

In 2011, in what many see as evidence of hope for Myanmar’s fledgling democracy and the environmental movement, President Thein Sein halted the dam’s construction and vowed the project will not proceed for as long as he’s in office.