Men wielding helium balloons stepped out of a car in Kampala’s bustling downtown on the morning of August 1, releasing them one by one into the open sky. Onlookers watched and wondered what the colorful display was all about.

A few hours later, a video emerged online of another activist releasing balloons atop Naguru Hill, the highest point in Uganda’s capital city. In the video, the activist explained that the balloons carry a message announcing the launch of a new activist toolkit, Beautiful Rising, aimed at helping people put an end to injustices like militarism and dictatorship.

Beautiful Rising’s reach, however, extends far beyond Uganda. Comprised of community organizers, trainers, tech gurus and writers across six continents, the Beautiful Rising team is working to broaden the relatively thin library of resources on creative nonviolence and social change strategy. What’s more, they’ve done it in a way that takes into consideration the concerns of activists in the global south: security, accessibility and usability.

Contributions from the global south

While working with ActionAid International — a global civil society federation devoted to issues of corruption, poverty and human rights — Danish activist Søren Warburg noticed a very significant shortcoming within the global community of nonviolent activists: a lack of idea and resource sharing.

“There has been very little cross-movement learning from successes and failures,” said Warburg, who then got the idea to spearhead Beautiful Rising. “A lot of resources in the nonviolent direct action catalogue come from the global north, yet courageous activists in the global south are living a whole other political life.”

Warburg realized that — beyond using his professional position to network across more than 40 countries — he would need to take an external look to social and political movements on the ground. This led to a deepening of his past connection with Beautiful Trouble, a group aimed at codifying the innovations of activists in various forms, including a book that offered a starting point for the toolkit.

“The idea was to merge the Beautiful Trouble analytical framework of creative activism to the lived realities of activists in the global south,” Warburg noted.

The partnership still recognized the short length of their tentacles in global south networks, so an advisory board consisting of members throughout the world was convened. (Full disclosure: My wife Suzan and I were among those invited.) The advisory network helped the team roll out regional collaborative workshops over the past two years in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Mexico, Zimbabwe, Uganda and Jordan, where content for the toolkit was gathered and pocket versions of the “Beautiful Trouble” book were distributed.

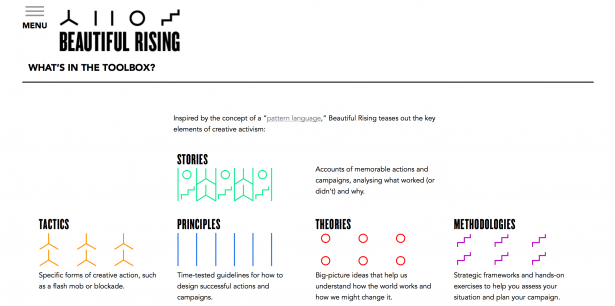

These workshops included many components of a standard nonviolence workshop with modules on nonviolent discipline and power analysis, but also included sessions on content writing — something many participants cited as the most useful session to their own learning. Completed contributions were added to the toolkit’s various modules under headings of principles, tactics, methodologies, stories and theories.

Some of Warburg’s favorite tactics included in the toolkit are “panty power” from Myanmar, clandestine leafleting with ping-pong balls from Syria, grandmothers stripping naked and unemployed youth releasing yellow pigs — both from Uganda.

“One of the things that cuts across these stories is ‘burn bright, but don’t burn out,’” Warburg explained, referring to the need for self-care and momentum building within movements. “It’s a tiresome job and a risky job.”

Ugandan contributor and artist-activist Helena Okiring praised the participatory process and the impact it had on her own learning. “Being able to put a method to the madness of community organizing makes it easier to engage more effectively and sustainably,” she said.

Surveys by other participants also indicated that time reflecting on their own experiences gave them a greater sense of connectivity to other members of the global struggle for liberation.

“Behind the toolkit is a global network of activists who are seeking to learn from each other and to share their stories,” Warburg said. And thanks to the painstaking work of multilingual activists, the toolkit is available in English, Arabic, and Spanish.

Bottom-up approach to content compilation

While much of the literature on nonviolence has grown out of academia, ideas contributed to the Beautiful Rising toolkit come directly from practitioners themselves.

The idea is that these people know what works and what does not work. They live out their ideals and understand the challenges they face, making them the most qualified to provide insights to fellow activists across the globe.

“This toolkit has employed a concept called ‘failing forward,’” Warburg explained. “You need to fail as much as you can, as fast as you can, so you don’t spend a lot of resources in terms of time and money developing something that is not sustainable. I think the donor community can learn a lot from this project in terms of how we have cooperated with people and tapped into networks.”

While a few ideas were grabbed from existing literature, community organizers involved in assembling the Beautiful Rising toolkit gathered the majority of their content through the extensive networks and connections they have built. This enabled them to gather a wide array of submissions, even from places they couldn’t physically visit or research online.

Visitors to the Beautiful Rising website can even input their own content to be added to the catalogue.

Content was not the only thing that members of movements contributed to the toolkit. They also guided its overall design.

Diana Haj Ahmad of The Public Society, team leader of the design aspect of the toolkit, facilitated multiple co-creation sessions in which various stakeholders gave direction to her work on the toolkit. “There’s no need to shelter the design process from the audience and team involved, because we’d come up with a much better solution all together,” she said.

Low/no-tech accessibility on multiple platforms

One challenge Ahmad and her colleagues took into account was the limited connectivity of users in the global south. This led to the building of a low-bandwidth website, as well as a downloadable and printable offline board game that can also be used as a strategy tool for movements and campaigns. A chatbot for messenger applications like Skype, Telegram, and Facebook Messenger was also developed for medium-bandwidth users.

The board game includes a pyramid that helps users determine their vision, mission, strategy, objectives, and risks they are likely to encounter. A second board and deck of cards for resources precedes the final game board and playing cards, with which users decide what big ideas, principles, theories and tactics they are going to follow before they creatively present them to the whole group. While the game can be played competitively with democratic scoring, it can also be used independently to guide strategic thinking.

The website version of the toolkit — equipped with all principles, tactics, big ideas, stories and theories — requires the highest level of connectivity for the full experience, but is still fairly accessible on many slow connections. A visitor to the website can arrange ideas directly in his or her browser and return to them later.

Deletion of browser history will erase any progress saved on the site. An option for registration at the site was never developed for security purposes.

Maneuverability for strategic planning

The website, game, and chatbot for messenger applications were each designed for usability. “We thought about how to make the toolkit as ‘sticky’ as possible. It had to be easy to access, easy to share, easy to add to,” said toolkit editor Dave Mitchell.

According to Warburg, “The very design and build of the toolbox should serve the content back to movements in a way that works for them. Is that a 600-page report? Maybe not.”

Rather than being a list-like compilation of creative actions and ideas, the toolkit is made to work like a toolkit. It is not merely an information database.

Mitchell said, “The first thing that sets Beautiful Rising apart [from previously existing resources of its kind] is its structure — its modular, interlinked, infinitely expandable pattern language form.” Users can drag modules around on their tables or in their screens.

“This provides organizers with a nimble and responsive framework for thinking about their own activism. We’ve seen how effective this framework is for allowing activists to think more strategically and creatively about the options they have and how they might respond most effectively, often in extremely challenging situations.”

The aesthetics have an ethic of their own, too. Different symbols represent different categories of modules.

“Once you expand the reach of the toolkit across different countries to become more inclusive and global, iconography becomes a bit more problematic,” said Ahmad. “We wouldn’t want it to be associated with any negative symbolism, so we’ve decided to move away from iconography and create a patterning system.”

Ahmad says there are two benefits to this system. The first is a universal language that transcends verbal communication. The second is the provision of a type of toolkit anatomy that shows how concepts connect to one another.

The future of nonviolence toolkits

The Beautiful Rising toolkit already has a diverse community of users by virtue of having been built by activists themselves. Its geographic reach, content and structure will provide countless assets to those waging nonviolence near and far.

Yet a few matters are admittedly outstanding.

“Our starting point [in the global north] was a bit weird,” Warburg confessed. “The challenge has been to build workshops facilitated in a way that we are able to connect with people and connect them with each other, while strengthening the toolkit without being preoccupied with outputs. Too often we spend a lot of money on a project because we have a product we want to launch, prohibiting us from effectively learning from our failures.”

While Warburg’s criticism of a toolkit he helped engineer may be valid, Beautiful Rising has been guided by the expertise of more than 100 activists worldwide. There may be room for improvement, but this toolkit is certainly nothing less than a step in the right direction for strategists. After all, a toolkit is — more than anything — just a starting point.

Although the concept of releasing helium balloons is aesthetically pleasing, the actual results of balloon release is disastrous. Please discourage all you know from releasing helium balloons – they burst and land in water where the balloon fragments are eaten by sea life with deathly results, as they are not eliminated or vomited out. Especially sea turtles are damaged by balloons, and in some places the sea turtle population has been decimated by 70-80%. Surely activists can find better ways of promoting their toolkits! http://www.balloonsblow.org

You have said it all Kree arvanitas! I could not agree less.