Two decades into the 21st century, one would expect all manner of “new and innovative” activism, right? Even Gene Sharp — the grandfather of cataloging nonviolent tactics, who published a list of 198 methods back in 1972 — fully expected the 21st century to be a time when we would have moved beyond learning about nonviolent action and toward perfecting its use. But it sure doesn’t feel like that is the case right now. From many vantage points, we seem firmly entrenched in a dystopia. Closing civil society space, encroaching authoritarianism in many countries, increasing environmental, climate and humanitarian crises — it all seems too daunting to tackle.

Still, creative activists continue to respond, as resistance — especially in the growing number of repressive regimes — is not only necessary, but necessarily dependent on creativity and innovation for its very existence. In fact, we may not have perfected using nonviolent action to build people power, but we have moved way beyond Sharp’s 198 methods. A new study has noted more than 300 methods of nonviolent resistance, representing plenty of innovation, specifically on the tech and digital front. And some of this technology has contributed to the record number of people participating in activism in the past couple of decades.

In the United States, there has been an uptick of dissent and increased involvement by those who are motivated to defend, protect and build a better world, following attacks on social services and human rights in the Trump era. All through history, the vanguard has often been indebted to the leadership of youth — and right now there is a swell of young people leading the way on the critical issues of our time: climate chaos, gender-based violence, immigration, racial justice and gun control.

At the core of these rising numbers is the increased accessibility and advancement of specific technologies — namely, ones that help activists use mass communication tools more easily and cheaply.

The mass mobilizations that have shown the most power have come from very specific marginalized communities. The largest ever single day of protest in the United States was the day after the 2017 presidential inauguration, when 3-4 million showed up for the women’s marches across the country. Beyond the U.S. borders, the 2010-2015 Arab Spring was a time of great mobilization in half a dozen countries by citizens attempting to bring down regimes and uphold civil society. Meanwhile, on Jan. 1, 5 million women and allies formed a 385-mile long wall across the Kerala region in India to support women’s equality.

At the core of these rising numbers, however, is the increased accessibility and advancement of specific technologies — namely, ones that help activists use mass communication tools more easily and cheaply. This, in turn, supports larger, dispersed, sometimes anonymous — and therefore less risky — tactics. Of course, oppressive regimes and other malevolent forces are oftentimes making equal use of these technologies, meaning activists have to stay one step ahead. So, let’s dig into some of the main technological advances helping activists to become more effective at leveraging resources towards that world we hoped to have by now.

Digital and mass communications

The increased affordability, capacity and versatility of cell phone and other digital technology — including video, photography and live broadcast capacity — have been the driving force behind DIY media and social media networks, digital memes included. Facebook Live and the ACLU app Mobile Justice not only enable campaigners to report from a hearing or demonstration in real time, but also to document the behavior of law enforcement as it happens. Meanwhile, memes have become the omnipresent visual communication form of social media from Facebook to Twitter. Within some of these platforms, enclaves like “Black Twitter” have blossomed, using hashtags to connect slices of specific communities across the globe. From #NotMyPresident to #BlackGirlMagic to #MeToo to #FeesMustFall — hashtags are now a feature of our cultural landscape. The sheer volume of digital communications is notable: For example, MoveOn says its volunteers sent 35 million peer-to-peer text messages to potential U.S. voters in 2018.

It wasn’t too long ago that the ability to live broadcast required expensive equipment and contracts for transmission. Smartphones of all kinds and the growing availability of broadband, as well as cell networks, have made live broadcasts and real time streaming accessible around the world. The implications of this have democratized who can report the news and who can watch whom, speeding up the news cycle — sometimes to our detriment — even while providing almost instantaneous opportunity for activist mobilization. But the recent gutting of net neutrality laws means activists will have to fight to retain the benefits of these advances.

The question remains: What kind of impact does this virtual activism have?

It was no surprise that activists heavily used social media to get a message of #resistance out after the U.S. elections in 2016. More unusual were the rogue or alt-Twitter accounts set up by disapproving Federal Agency employees as they were targeted by the Trump administration, such as @altUSEPA and @AltDptEducation. There was a rather poetic beauty to these actions since Twitter is the president’s preferred mode of communication with the U.S. public.

Of course, the growth of social media has sparked a hot discussion about the effectiveness of this form of communication. While it is undeniable that the number of people using social media has grown exponentially in the last two decades — along with the number of people signing petitions and emailing their elected officials — the question remains: What kind of impact does this virtual activism have?

Back in 2011, Avaaz reported that about 10 million people across 193 countries had taken part in close to 46 million of their “actions” (i.e. Avaaz-branded emails, phone calls, fundraisers, rallies, etc.). Are those actions a poor substitute for personal involvement? Did they detract from time that could have been spent off-line in more impactful ways, especially on issues that require direct intervention? Take, for example, the most recent U.S. federal shutdown, which ended when no-show unpaid airport workers forced airports to close — not when social media outrage reached a particular pitch.

Around the world, from Tahir to Maidan Square, most agree the Facebook revolution is a myth — even while acknowledging the impact social media can, and has had, on mobilizing at a scale critical for catalyzing people power.

Digital get out the vote

Online dating: OK, let’s go there. It’s not new, of course, but it has newly become a way to mobilize people to get to the polls — whether it’s Tinder, Grindr, or OKCupid. Some sites are not happy with soliciting or “Tinderbanking.” (Yes, someone even coined a name for it.) Two British women figured out how to get folks to loan their profile to a chat bot to engage in dialogue encouraging the suitor to hook up with the political process — not just a date. This was especially important in the United Kingdom, where younger voters are disproportionately unregistered and, therefore, unable to vote.

Meanwhile, in the United States, there is even an app called VoteWithMe. It works with your cell phone contacts and can tell you a person’s voting history and whether they are in a flippable state. It was designed to increase the number of people who vote — because research shows that a personal reminder increases the likelihood of someone actually going to the polls.

Even the mundane conference call has morphed into a huge platform, particularly as advances in video conferencing have made it much easier to use than even 10 years ago. Not only does this technology support organizing, it also allows for virtual trainings and international connections at an unprecedented scale. Some action/campaign coordinated calls have had upwards of 60,000 participants. In fact, tens of thousands of MoveOn members joined their online training calls in 2018.

Digital mapping

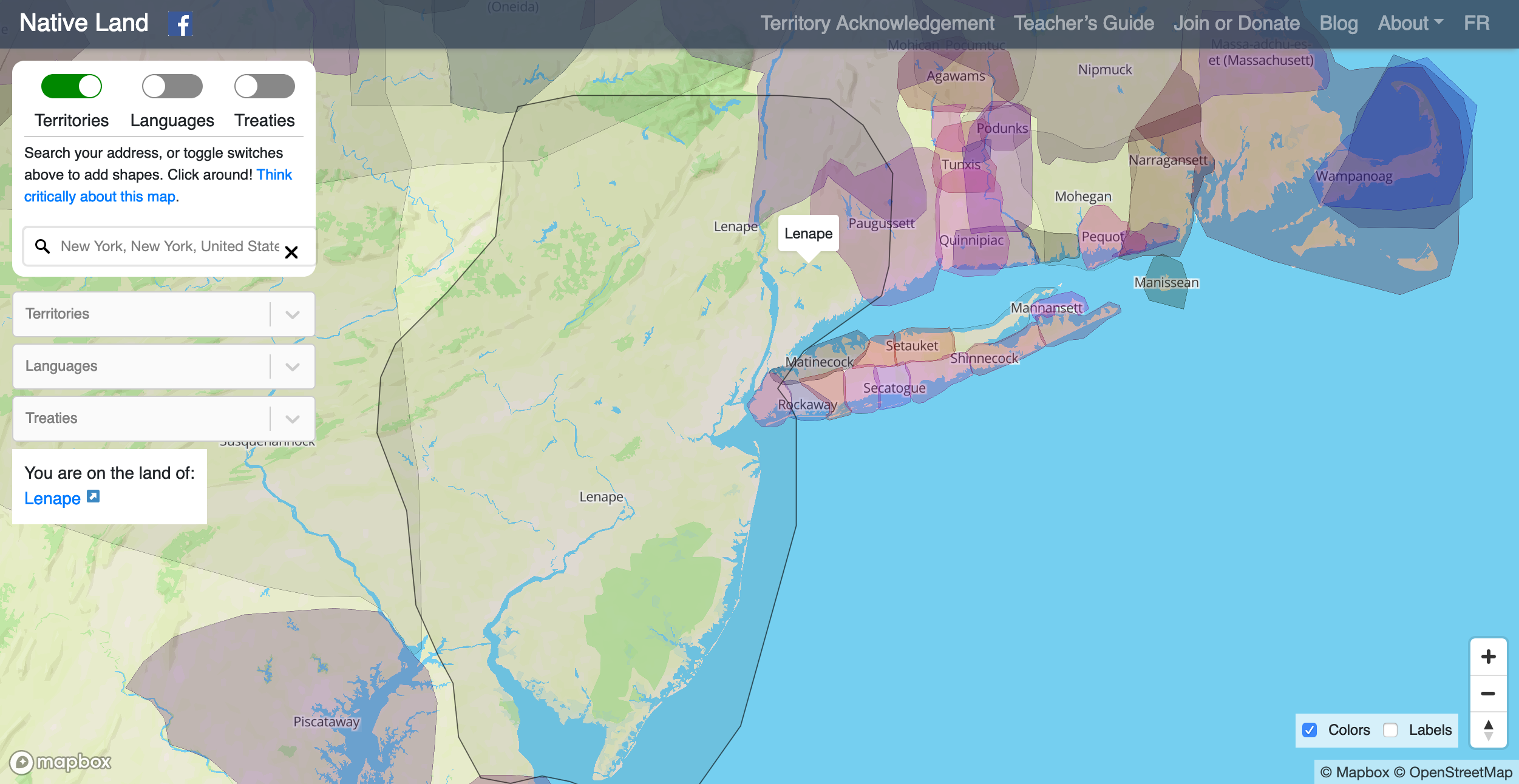

Another widespread integration of new computer technology has fueled the accessibility of data visualization. Creative activists have used mapping in many ways to help “make the invisible, visible” — often one of the first challenges that activists on complex, hidden or distant issues face. For example, many aspects of climate change can be predicted and shown by geographic area on interactive maps, whether heat index, sea level rise, fire or drought risk. Activists working on indigenous and First Nations’ rights often find that current inhabitants have limited or no knowledge about the places they live. Want to know the indigenous history of the land you are living on? Enter your zip code into this app and you can find out.

Drones

Sure, high-flying remote-controlled technology has been around for a while, but the advent of mass produced small, cheap and, therefore, accessible drones has opened up a world of aeronautic protest and documentation for ordinary folks. It has included the surveillance of game poachers and commercial outfits in hard-to-access, protected areas. Drones have also been used to fly abortion pills into countries that have outlawed their access, and they have documented authorities illegally attacking water defenders at Standing Rock. Greenpeace crashed a Superman drone into a nuclear power plant containment dome to expose its vulnerability just months ago.

Crowdfunding

Innovation and tech advances have made it possible — in theory and sometimes in reality — to crowdfund solutions to seemingly intractable economic justice issues. Theoretically, the “Greek Bailout Fund” campaign could have raised enough money to help Greece avoid austerity, even as it did expose the unjust system. On the other hand, an almost $32 million of medical debt has been forgiven by online crowdfunding to purchase debt for cents on the dollar, and then forgive that debt. The National Bailout program also provided direct relief through a mass donation to bailout black mothers and others affected by mass incarceration.

Projections

We can now safely self critique and admit that early activist light projections were either tiny and poorly lit, or required outrageously delicate and expensive machines with high energy needs. The technology has shifted so dramatically in the last few years that it’s almost a new ball game. Projectors have not only become much more powerful, efficient and smaller — they have also become way more affordable. Mapping programs have improved as well, enabling an artist with a photo of the target building to turn their computer into an architectural wizard.

Whether it’s the symbolism of shining a light on something to expose a wrong, or just its ephemeral nature — a statement seemingly coming from nowhere and gone in an instant — there’s a current love affair with large scale illuminations right now. In 2012 Egyptian activists projected videos of military repression onto prominent buildings. Meanwhile, in 2018, Americans projected images of the slain journalist Jamal Kashoggi onto a part of the Newseum, which has a quote from the first amendment. Part public service announcement, part luminous artistic statement, projections are used to glowing effect around the world.

An update on projection technology wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the world’s first holographic protest march, which took place in Spain in 2015. The surreal threat of outlawed public protest drove artist-activists in the group No Somos Delito (We Are Not a Crime) to fight back in an equally surreal way. It was considered a big leap for how technology is used in activism.

Inflatables

Not just full of hot air, inflatables have been making big impressions lately. Beyond the longtime practice of unions using giant inflatable rats to expose scab establishments, the recent appearance of “Baby Trump” and “ChickenHawk Trump” balloons have lifted protest props to a new height.

Birddogging on steroids

The old school tactic of birddogging — or pursuing elected officials to get them to comment on specific issues in order to hold them publicly accountable — has been employed at a much larger scale recently. Over the last couple of years, immigrants, women and anyone needing health care were faced with the increasing federal and state curtailment of a their right to control their own bodies.

This manifested publicly in the controversy surrounding the nomination of right-wing judge Brett Kavanaugh for the U.S. Supreme Court. Coordinated teams of birddoggers in the Senate and House office buildings delivered hundreds of face-to-face interactions in the very short timeline of the nomination hearings. It got so intense that specific senators avoided the halls of Congress for fear of being questioned by constituents. The flip-flop of Sen. Jeff Flake after one of these moments went viral.

Unfortunately, the backstory of the intentional organizing of this tactic by the Center for Popular Democracy, Housing Works, Ultraviolet and NARAL did not reach the wider public. But it is worthwhile to consider how upgrading, or scaling up, tried and true tactics can deliver results.

Healing as resistance

Beyond numbers and technological innovations, one of the critical contributions of the Movement for Black Lives, or M4BL, and organizers with #BlackLivesMatter have offered by example to the broader activist community is the emphasis on healing and joy. This is not an overall new approach, but rather a resurgence of attention being paid to trauma awareness, self care and the future that is being created from the black radical tradition. (Not too long ago, free school breakfast programs grew out of a Black Panther social program.)

It manifests in making time for public and private community events highlighting black culture, as well as in community healing circles. An emphasis on healing justice and embracing the positives in M4BL grew out of the need to fight systemic racist oppression and — at the same time — uplift black lives and resilience. This current emphasis on infusing healing and humanity into activist campaigns is a gift to the broader movement for social justice — truly addressing the radical and essential root of transformative work.

And, hopefully, when we look back at early 21st century activism, we will see the creative and cultural aspects highlighted above continue to be cornerstones of ever more effective people-powered movements. Successful campaigns share not only strategic thinking, but also creativity, innovation and escalation of tactics by ever larger numbers of participants — exactly what we need to realize the healthier, more equitable world we strive toward.

Instead of the obvious clean energy startups, this competition funded by the estate of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry is helping to fund projects that end food waste or support women’s rights.