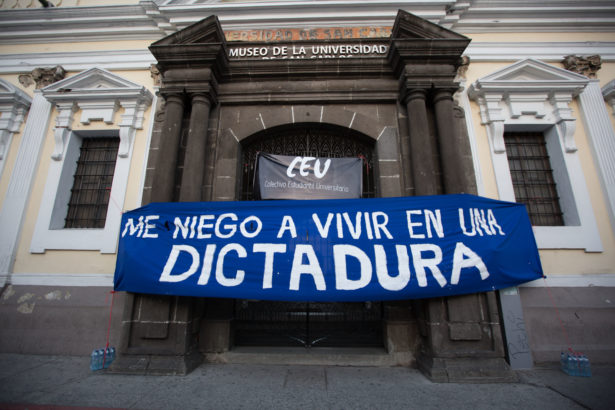

Late in the afternoon on July 29, students from Guatemala’s only public university, the University of San Carlos, took control of the university’s museum in Guatemala City’s historic center. Their goal was to block the country’s congress from holding sessions there, as the congressional building undergoes remodeling.

“The facilities of the university are part of our heritage. Here great thinkers were formed,” said Lenina García, the general secretary of the Association of University Students Oliverio Castañeda de León, or AEU. “It is despicable that the congressional representatives want to meet here when they have supported laws that are regressive. We believe that it isn’t correct, and we do not want to be on their side of history.”

The occupation was launched in part due to fears that the Guatemalan Congress could hear debates and possibly pass the controversial “safe third country” agreement with the Trump administration, which was signed in the White House by Guatemalan Minister of the Interior Enrique Degenhart on July 26. The agreement will require asylum seekers from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to apply and wait in Guatemala for their cases to be approved in the United States.

The signing of the agreement was the last straw in increased tensions at the university. The occupation quickly brought up other frustrations with university Director Murphy Paiz, who took the position in 2018. Students accuse the director of treating the university as his personal plantation.

“The agreement was the last drop that overfilled the cup,” said Amparo Gómez, the secretary of university affairs for the student association of the School of Political Science. “We have seen that there is not a willingness to address the problems that the country and the university faces.”

In the hours that followed the occupation, the Guatemalan Congress issued a statement that it would relocate the sessions that were scheduled for Tuesday. Yet, in spite of this announcement, students maintained their occupation, calling on other students to join.

While the occupation was sparked by the proposed congressional session in the university’s museum, it became a catalyst for action by students across the country who are upset about the politics and conditions of the University of San Carlos. The occupations of other universities quickly expanded in the days that followed. By Aug. 3, students had occupied 24 campuses of the university in 19 of Guatemala’s 22 departments, including centers in Guatemala City, Huehuetenango, San Marcos and Quetzaltenango.

The AEU and other student organizations have called on other students to join in the protest against the privatization of the country’s only public university. The student groups have built off the occupation of the museum and organized a national movement for access to public higher education.

“Our occupation is permanent until they respond to the demands,” García said. “We are calling on other students to join in the defense of higher education.”

Expanding protests against privatization

Founded in 1676 during Spanish colonization, the University of San Carlos is a historic institution in Guatemala. Over the centuries access to higher studies was opened to more and more students, and to this day it remains the only public university in the country.

Upon taking control of the museum, students accused officials of attempting to “privatize the university” through cost increases — which have steadily risen — and transforming the university’s culture by signing agreements that students argue cede more space to private companies.

“Since Paiz became director, he has pushed politics of privatization of the services of the university,” Gómez said. She points to the fact that prior to the appointment of Paiz, students paid 350 Quetzales (or about $46) for the Preparatory Academic Program — a nine-month program with physics, language classes, mathematics and chemistry that prepares students for university classes. Following the appointment, Paiz increased costs of the program to 1,000 Quetzales (or roughly $130).

“These courses are optional, but we consider it to be a right to higher education that they are violating,” Gómez said. “This cost is extremely high. It restricts access to higher education for many students.”

Nearly 60 percent of Guatemala’s population suffers from poverty, according to 2014 data from the World Bank. This high cost for entry-level courses especially affects students from rural areas and those living in poverty from accessing the university.

Students are rejecting other actions of the university director, including the signing of an agreement with the Chamber of Industries of Guatemala, which will require students to do their internships and investigations — known as Ejercicio Profesional Supervisado, or EPS, in Spanish — with private companies. The program was set up in the 1970s and placed students in public institutions and organizations to investigate and respond to problems in forgotten parts of the country. It was meant to be a program that exposed the students to the situations that exist in the country.

“The EPS is meant to return something to the people of the country,” said Gabriel Morella, a 27-year-old engineering student from Guatemala City who was part of the occupation of the museum building. “But [the agreement] breaks apart the program.”

The students entered into a dialogue with Paiz on Aug. 2. The dialogue is being mediated by the country’s Human Rights Ombudsman, Jordan Rodas. Students have maintained that they will continue their occupation until Paiz meets their demands.

‘Guatemala is not a safe third country‘

While the occupation has brought to light deep frustrations within the national public university, the root cause of the current occupations remains the “safe third country” agreement with the United States. For students, this agreement will only exacerbate the social crisis that exists in Guatemala.

Faced with the occupation of the museum in Guatemala City’s historic center, the country’s congress moved sessions to the Westin Camino Real hotel in an affluent part of Guatemala City. The session on July 31 was met by a group of nearly 30 students from the Strike Committee of the School of Agronomy, who were joined by urban collectives and other organizations outside the hotel.

The protest was organized due to fears that the country’s congress was to discuss the “safe third country” agreement with the Trump administration. Students chanted “we do not want to be a colony of the United States” as congressional representatives met inside the hotel.

The agreement is being met by outrage on social media and in the national media. Many argue that the agreement is illegal due to the fact that the agreement was signed without the country’s congress and violates a court order against the agreement. Furthermore, many point out that Guatemala cannot be a safe country for migrants.

“The agreement puts Guatemala in a state of destabilization,” Morella said. “Migrants will come to the country and there will need to be the guarantee for certain rights, including health, work and housing. If Guatemala cannot provide these basic things for its own population, how will it do it for the migrants who arrive?”

While the congress did not discuss the agreement in the July 31 session due to the fact that they have not officially received the accord, it remains a looming threat in future congressional sessions.

Guatemala continues to suffer from poverty, lack of access to health care and education, high rates of crime and violence, and corruption. Yet, in spite of this, the Morales administration signed the agreement after Trump threatened to block Guatemalan exports and to enact tariffs on remittances sent to the country by families living in the United States.

This is especially troubling after the Morales administration evoked sovereignty in their struggle against the U.N. backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, which has investigated and led to the arrests and prosecutions of officials, drug traffickers, and business leaders accused of corruption and illicit activity.

In August 2018, Morales announced he was not renewing the commission’s mandate after it opened an investigation into him and his family. The commission is set to end on Sept. 3. Morella and others have accused Morales of selling out the country.

“Now where is the sovereignty of the country?” Morella asked.