Guatemala is facing one of its most critical political crises in the last three decades following the surprise victory of progressive anti-corruption presidential candidate Bernardo Arévalo on Aug. 20.

The crisis stems from what many Guatemalans see as an attempt by officials accused of corruption to undermine and cast doubt on the legitimacy of the results of the country’s democratic process in order to protect their interests. In response, citizens and social movements have mobilized to defend the Central American country’s democracy as public officials attempt to undermine the will of the people.

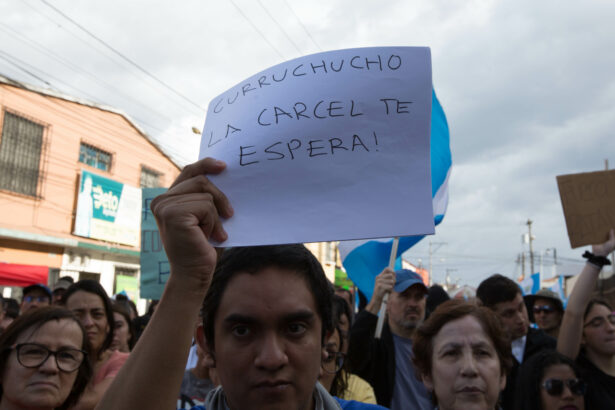

Since early July, citizens and organizations have mobilized almost weekly protests to decry the interventions in the electoral process and to demand the resignation of Attorney General María Consuelo Porras and Rafael Curruchiche, the head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity, commonly known as FECI. The calls come after both sought to undermine the results of the presidential elections by opening criminal investigations against the party and the head of the national citizen registry (which grants parties legal status). They also sought to investigate the heads of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and illegally suspend Arévalo’s party just as the transition began on Sept. 5.

These attacks on the democratic process and efforts to undermine faith in democracy have become all too common in recent years, as authoritarian regimes have gained more power across the hemisphere. In Guatemala, the extra-legal means used by officials to cast doubt on Arévalo’s victory echoes the playbook of conservatives in the United States following Joe Biden’s election in 2020.

In July “we asked within the collective what we should do. This is an emergency for us, and this is something serious,” said Elena, an organizer with the anti-corruption group Justicia Ya in Guatemala City, using a pseudonym out of fear of retaliation.

Justicia Ya emerged in the 2015 protests against the corruption in the administration of Otto Pérez Molina. Guatemala erupted in months of weekly protests after an investigation by the internationally renowned and United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, commonly known as CICIG, uncovered a graft network in Pérez Molina’s administration that stole millions of tax dollars. The protests culminated in the resignation and prosecution of Pérez Molina and members of his cabinet.

Justicia Ya has remained active in the years since the protests, regularly organizing against and denouncing acts of corruption in the administration of Jimmy Morales and the current administration of Alejandro Giammattei. They are one of the many groups and individuals who have raised their voices against the current threat against Guatemala’s weakened democratic system.

Both Porras and Curruchiche have rejected these accusations of intervening in the electoral process, with Porras saying that the “public prosecutor’s office is not political.” But Porras has sought to stifle criticism by seeking to limit freedom of speech on social media through the country’s Constitutional Court. She filed an injunction against users and journalists who criticize her, which the court rejected on Aug. 28. Porras and Curruchiche are both sanctioned by the United States through the Engel List of corrupt and anti-democratic actors.

People began to organize to defend their vote shortly after the first round of voting on June 25. This led to a surprise run-off election pitting Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party against candidate Sandra Torres, a businesswoman and former first lady with the National Unity of Hope party, who has moved to the right in recent years. Arévalo had previously been polling in eighth place ahead of the general elections, which had already seen the suspension of candidates on both the left and right who were viewed as threats to those at the top of Guatemala’s unequal social and political system.

The first attempts to undermine confidence in the elections occurred in early July, when parties that lost took their challenge to the Constitutional Court and demanded a revision of all vote tallies. Seeking to gain support from the most conservative sectors, Torres and her party suggested that there were irregularities in voting, contributing to the current crisis.

Over the following weeks, the attorney general’s office and anti-impunity prosecutors attempted to illegally suspend the legal status of Movimiento Semilla over allegations that more than 5,000 signatures were falsified to form the party. They subsequently ordered the electoral body to suspend Movimiento Semilla on two different occasions. In early September the electoral authority overturned the decision.

The Movimiento Semilla party is a relatively young party in Guatemala, forming officially in 2017. But there are deep connections between the anti-corruption movement and the progressive party, as they both grew out of the protests in 2015 against corruption.

On Sept. 12, investigators raided the offices of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the citizen registry, and the facility that houses the ballots and tally sheets from the first round of elections. During the raid, investigators illegally opened a number of boxes containing ballots from the first round as part of an investigation into accusations of fraud levied by the party that lost the presidential election.

The raids have led to further calls to protest in defense of the country’s democracy.

President-elect Arévalo and his vice-president, Karin Herrera, held a press conference to decry an attempted technical coup d’etat against his administration even before the transition began.

“For there to be a genuine possibility of democracy and a government that can really work for the people Porras cannot continue to be there” as attorney general, said Gabriel Wer, one of the founders of Justicia Ya. “There is a long list of illegal actions” that she has carried out, “including the attack against democracy.”

A democracy in crisis

In the years since the closure of CICIG in September 2019, Guatemala has seen a rapid rollback of anti-corruption efforts. Since 2021, a coalition of Guatemalans tied to the business sector, political elite, and the military who were once investigated for acts of corruption by the CICIG have carried out a campaign of revenge against those who were involved in the struggle against corruption.

At least three dozen judges, journalists, prosecutors, investigators and activists have been forced into exile, including Wer, who fled the country in February 2022 pending investigations under false pretenses. Others involved in anti-corruption efforts have faced criminal prosecution, including journalists who investigated acts of corruption.

In June 2023, a Guatemalan court convicted José Rúben Zamora, the award-winning founder of Guatemala’s investigative newspaper El Periódico, to six years in prison on charges of money laundering. The case has been seen as an attack on press freedom in Guatemala, especially after the paper closed in 2023.

As a result of these attacks, there were great concerns ahead of Guatemala’s presidential elections, given the rapid deterioration of the country’s democratic institutions during President Alejandro Giammattei’s administration. International organizations and foreign governments expressed worry with the arbitrary exclusion of candidates from participating in the presidential election, including popular leftist Thelma Cabrera of the Movimiento para la Liberación de los Pueblos party and conservative populist Roberto Árzu of the Podemos party.

Concerns escalated just 30 days before the general elections when the candidacy of right-wing populist Carlos Pineda was suspended. He was leading in the polls at the time, and his exclusion made voters believe a path was being opened for either Zury Rios, the daughter of the late Guatemalan dictator Efrain Ríos Montt, or career diplomat Edmond Mulet to win the elections.

But the success of Arévalo — the son of one of Guatemala’s most popular presidents, who ushered in the period known as the Guatemalan Spring — came as a surprise to Guatemalan citizens, but also analysts and observers. His victory in the run-off brought hope to those who have faced intimidation and attacks for their struggle against corruption.

Organizing on every level

Mobilizations in defense of Guatemala’s democracy have become a common sight over the weekends in Guatemala City, across the country and in immigrant communities in the United States. Indigenous communities have also gotten involved, with some community ancestral authorities threatening to block highways if Porras and Curruchiche do not resign.

While the majority of protests have been relatively small, there is growing clamor on social media demanding that those attacking Arévalo respect the will of the people. “Right now we are seeing symptoms of something that had already changed years ago,” Elena said. “I think it’s a mixture of people being fed up with the political class and corruption. It’s no longer sustainable.”

“Before the first round there was a lot of hopelessness,” she added. “But after the second round we realized how many people we have with conviction, hope and the joy of imagining that it is possible to achieve the impossible.”

On Sept. 8, a campaign began to spread on X, formally Twitter, using the hashtag #adiosconsuelo, or “goodbye Consuelo,” including an image of a hand waving goodbye to the embattled attorney general. The hashtag has been used over 25,000 times since it first appeared. This builds off the work of another citizen who collected over 220,000 signatures on a Change.org petition calling for Porras’ resignation. These signatures were presented to the public prosecutor’s office.

While social media, like WhatsApp, X and Facebook, have played an important role in the organizing of Guatemala’s civil society, Instagram and TikTok have proven to be the most useful for organizers.

“TikTok allowed or facilitated a lot of organization of people organically,” Wer said. “It is a network that really has a fairly strong reach and is quite broad in age, and in geographical location. And people made their own videos or commented on videos that other organizations made.”

The defense of Guatemala’s democracy is occuring not only in the streets, but also in the courts. Organizations have sought to slow the attacks against the president-elect’s party and the attempts to limit the freedom of speech in the country’s courts. Lawyers from organizations have filed multiple challenges in the Constitutional Court, the country’s highest court.

“We have had to present constitutional actions to defend the rights of the population in general during the electoral process,” said Edie Cux, a lawyer with the Guatemalan transparency organization Acción Ciudana. The organization has had to “guarantee that the popular will is respected and complaints were filed against the judges and prosecutors who have somehow affected the electoral process.”

People continue to speak out

There are nearly four months between now and when Arévalo will take office on Jan. 14, 2024. Pro-democracy activists will remain mobilized to respond to whatever attack comes against the president-elect. Those seeking to defend Guatemala’s fragile democracy know that their work is not over, especially given the attacks that have already happened. And once the new president takes office, the undermining of the new administration will likely continue.

“Things are not going to get easier,” Elena said. “The difficult part is really what lies ahead. But I think that if we take it on with a lot of audacity, with a lot of courage, with joy, not with pessimism, not with this defeatism, we will move forward. We will continue resisting.”

The international community has backed the results of the Aug. 20 run-off elections. The European Union, the Organization of the American States and the United States have upheld and defended the results of the election. The United States has recognized Arévalo as Guatemala’s president-elect, with Vice President Kamala Harris speaking directly with him. The Biden administration has also expressed deep concerns with the attacks against Movimiento Semilla.

“The United States remains concerned with continued actions by those who seek to undermine Guatemala’s democracy,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a statement on Aug. 29. “Such anti-democratic behavior, including efforts by the Public Ministry and other actors to suspend the president-elect’s political party and intimidate election authorities, undercuts the clear will of the Guatemalan people and is inconsistent with the principles of the Inter-American Democratic Charter.”

Support Us

Waging Nonviolence depends on reader support. Become a sustaining monthly donor today!

DonateFaced with these ongoing threats to Guatemala’s fragile democracy, the international community has sent observers to participate in overseeing the transition of power.

“The observation commission of the European Union was decisive, as well as that of the OAS. They maintained a very, very strong position in fact due to the violation of rights” through these attacks against the electoral process, Cux said. “The OAS appointed a Transition Commission, which are the officials who are currently accompanying this transition, and who have met with the Public Ministry, the government, the president-elect and who propose a defense for the popular will.”

But those who seek to undermine the historic victory have decried the international intervention, with Curruchiche directly accusing Luis Amargo, the president of the OAS, of interfering in Guatemala’s internal affairs.

As countries across Central America and around the world drift into authoritarianism, those who struggle for democracy in Guatemala hope their fight inspires others, just as the CICIG was once seen as an example for how to address impunity.

“In a world where democracy is in crisis, I believe that Guatemala can be the path to remember how to recover the importance of democracy and defend it,” Wer said.

This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.