My neighborhood in Chicago, “Little Village,” is the single largest jail site in the United States. The Cook County Jail is usually known as a place where violence occurs, like attacks on inmates and correctional officers, suicides and shootings outside of the courthouse. It has also become what the New York Times called a top national “hot spot” for the coronavirus in recent weeks. As of this writing a staggering 491 inmates and over 360 staff have tested positive for COVID-19. Six inmates have recently died because of the virus, and the numbers of cases continue to grow.

There are several important efforts taking place locally, like the Chicago Community Bond Fund and The Bail Project, to reduce the number of people behind bars during this pandemic. Their efforts can teach us about the importance of decarceration efforts for nonviolent offenders. By pooling community resources to get inmates out of jail, these initiatives help reduce the immediate risk of infection in the short-term. They are also building a vision of community-led responses to incarceration.

From my experiences working with incarcerated young men, I believe that inmates trained in nonviolence — even violent offenders — can help make positive contributions to the outside world. Incarcerated individuals can change on the inside, but they are often overlooked by the society outside prison walls. Now more than ever, when incarcerated people are so disproportionately at risk from COVID-19, it is important to remember the inherent worth of all people and to stand in solidarity with the communities most affected by crises like this health pandemic.

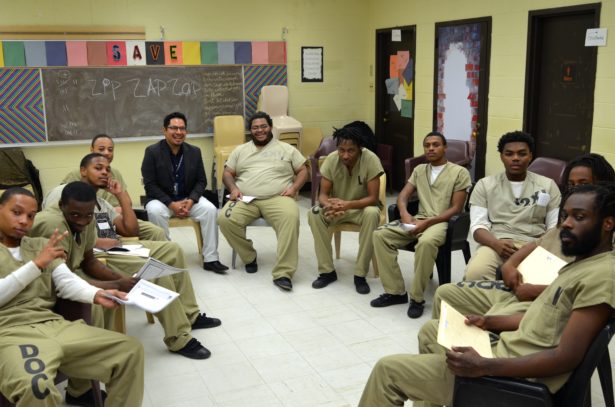

For the past three years, I have served as a volunteer facilitating workshops in peace and conflict studies in Cook County Jail. At our weekly sessions, we explore the power of nonviolent change with young male inmates detained for violent offenses, ranging from armed robberies to gang-related violence in their own communities. I’ve also had the opportunity to teach a master level course for North Park Theological Seminary on nonviolent conflict transformation at Stateville Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison just outside of Chicago. Like most jails and prisons in America, this one is filled with predominately African-American and Latino young men, all of whom participate in the training voluntarily. During my years teaching nonviolence to the incarcerated community, they have also taught me many lessons.

To learn nonviolence, we must unlearn violence

The first lesson is that in order to learn nonviolence, we first must unlearn violence. For individuals who have grown up where violence is the norm, this can be very difficult — but not impossible. Moreover, the incarcerated men I teach come from some of Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods. Not only that, but they represent the thousands of young people that are caught up in cycles of systemic and local violence. It is thus no surprise that many of my incarcerated students have been shot or shot at multiple times, and they speak openly about their personal histories living through cycles of violence.

Training in such an environment is as difficult as it is rewarding, since jails and prisons place limits on the instructor and students. Additionally, some inmates may not be receptive to the message of peace, love and nonviolence, or may feel that discussing these topics puts them at risk in this environment. I have been mocked, insulted and cursed at during these nonviolent education workshops. In a particular division, students are handcuffed to their seats for their own safety, as well as for the officers and mine. In spite of these barriers, the discussions in these sessions are powerful, and I am often struck by how the young men have been able to unlearn violence in the midst of such violent surroundings.

In other divisions, where students are not shackled during workshops, we explore violence and nonviolence through interactive activities. We once outlined an imaginary scale from one to 10 on the floor, and asked men to position themselves with respect to how they would rate the severity of striking a child with a belt, hitting a woman, and a drive-by shooting in which no one was hit. The discussion that accompanied each scenario was profound, and it allowed us to safely discuss our understanding of violence and how to redefine violence. In many discussions, we arrived at a conclusion that violence, more often than not, defeats its very purpose.

For some inmates, violence has become the norm and it is not their first or even second time in jail. This is the case with Devon (which is a pseudonym, as all the students’ names are in this story), who has been to County Jail three times and hails from the North Lawndale community. Devon is a tall, thin young man with tattoos on his arms and face. When I asked how he thinks people view his community, he said, “My community is a great one. The only thing is that there is a shadow that is cast over the community that gives it a bad reputation. The shadow of violence is what most people in the outside world see, and that is not representative of our neighborhoods.”

He has been one of the most engaged students in the workshops, so I asked if he would be willing to act as a voice for peace back in the neighborhood. He responded, “yes and no.” In other words, Devon said that he saw this as an important responsibility, but admitted a belief that it might be too late for him to transform his role in the community. He thinks nonviolence workshops should start with younger people. “If we want to make a difference, I would say we need to start teaching peace and conflict as early as possible, like the 6th, 7th or 8th grades,” he explained.

At Stateville Correctional Center, many of my students have lived behind prison walls for 15, 20 or even 30 years. Alvaro, a man from Little Village, is an ex-gang-member who has been involved in violence since his early youth. “We are no different than those on the outside,” he said. “We too have been wounded, traumatized and have experienced deep hurt in our lives … I would tell young people involved with violence today that they themselves have so much to give our society.”

“The shadow of violence is what most people in the outside world see, and that is not representative of our neighborhoods.”

When asked what it would take for there to be a reduction in violence in our community, he encourages caring adults to mentor young people who may be at risk of committing violence and take them under their wing. “We need a deep analysis of the root causes of violence,” Alvaro said. “We also need to meet one-on-one with these young people, and really hear them out and nurture them.”

For many of my students, this is the first time they have heard words like “nonviolence” or “peacebuilding.” Their backgrounds, stories and experiences of incarceration provide a deeper meaning when discussing ideas of peace and alternatives to violent aggression.

Systemic violence trickles down to local violence

The second lesson I have learned is that many young men in jail or prison share a similar and insightful perspective: that they come from beautiful communities worthy of recognition and respect.

Tabar, a heavyset young man from the Englewood neighborhood with dreads and arm tattoos, reflected on this point. “We are not a violent community,” he said. “We are a very nice community that is family oriented … It is just some circumstances that make some of our people crack under pressure.”

For people who have never lived or even visited our “hoods” this may sound strange. People assume that violence is the result of “bad” influences or hanging out with the “wrong” people. The pressures are instead the result of a violent system that has intentionally neglected poor people of color over generations. Malcom X once connected these dots, arguing that if you come from a poor neighborhood, that leads to poor schools, poor education, poor paying jobs and makes it next to impossible to break free from these systemic injustices. The cycle of violence begins with structural violence.

After all, people of color in our society have faced violent repression and oppression over centuries. Could the violence perpetuated in local poor communities be the manifestation of the violence our communities have received over decades? I believe there is a correlation between institutionalized violence and internalized violence, and the poor are always the most impacted.

At Stateville, Jay, a former-gang member from the Back of the Yards community who has survived multiple shootings wrote, “The layers of oppression run deep in the United States … Growing up in these cities, adolescents aren’t aware of the social constructs that are fueling systemic oppression … While children in America were pretending to be their favorite superhero, my friends and I were pretending to be the roughest and toughest character we knew.”

Jay’s reflection offers insight into the fact that many young people from marginalized communities who are engaged in violence might not know that they too are systematically oppressed. They have been surrounded by violence, which has informed their worldview and left few options besides the school-to-prison pipeline.

Jails make unique nonviolence training centers

My third takeaway is that jails and prisons offer a unique opportunity to train people. During some of our workshops, we explore the violence and nonviolence spectrum. We discuss the worst and best and “a’ight” actions to deal with real life scenarios and social problems in day-to-day conflicts. We explore if peace is just a bunch of “bull shit” or some “real shit.”

I have learned from these young men that peace is not an easy route. Real peacemaking takes heart and nerve when violence often dominates the narrative. I have taught peace in elementary schools, high schools and universities, at home and abroad, and I have had — without a doubt — my most profound and rich conversations exploring these subjects behind jail and prison bars. The young men are subject matter experts in violence and in peace, and they are much more attuned to subtleties in society and social interactions than most people.

At the county jail, Victor, a heavyset young man with glasses and a distinctive long haircut, expressed his views on the benefits of nonviolence training in jail. “I’ve learned a lot in these training sessions, especially the history of it,” he said. “Learning of the lives of Cesar Chavez and Dr. King, Ella Baker and Harriet Tubman, makes me want to do something positive for the society. Come to think of it, I’ve never done anything positive for the community. Once I get out, that is something I really want to do.”

Real peacemaking takes heart and nerve when violence often dominates the narrative.

We rarely study the lives and struggles of those who came before us and how they utilized strategies and tactics of nonviolent social change to confront violence. In formal school settings we might learn dates or events, but not the specific ways nonviolence and peace building was applied to defeat violence.

At Stateville, Brett, a thin young man with tattoos across his arms and neck, shared his story of how he went from Englewood to the Cook County Jail and ended up in Stateville. He asked me to share his story with the young people coming up in his neighborhood. “Many things happen that lead our people here, but it doesn’t have to be that way,” he explained. “We have the power to change how we act out in the world in the conflicts that confront us.” The next time we teach workshops in the Englewood schools, I told him, I would be sure to include his story of struggle and transformation.

Previous Coverage

The transformation of a warrior behind bars

The transformation of a warrior behind barsIt might be difficult for some to understand, but regardless of what violent crimes people have been accused of, they still deserve respect. Black and Latino men in our society have historically been denied respect and their right to be heard. These men are just like any one of us. They have families, communities, emotions and their own perspectives on society. They can teach us their truth and something about our own lives outside of prison walls.

The COVID-19 pandemic has effected all of us in more ways than one. In essence, nothing we do as a society will be the same again. This moment has allowed us to really deal with the struggles to advance life and what a just world truly looks like. This pandemic has impacted our most vulnerable communities — our elders, our poor, our sick, people of color, the incarcerated and their families. We as a society must also learn to humanize incarcerated communities.

We have to meet people where they are at. We should not indoctrinate them or lead them to join our campaigns, but only try to inspire them to discover their own journeys for life, truth, power and justice. Because of these young men, I’ve become a better person. Many incarcerated men and I can relate to Cesar Chavez, who said, “I am not a nonviolent man, I am a violent man trying to be nonviolent.”

This story is dedicated to our incarcerated community members who have passed away as a result of COVID-19, including two of my students from Stateville Correctional Center.

This is a very moving report, Henry. Your tribute to all the men – young and not so young with whom you have been working in Chicago recognises the value inherent in all of us – incarcerated or not – dealing with the traumas of our earlier lives or the injustices structurally built into society. I am a teacher (retired) and among friends out of that profession during our time teaching recognised that we were what we loosely described as social workers. We were not teaching subjects – even though that might have been the outward label – a Science teacher, an English teacher – a Home Ec teacher – we were actually teaching ethics – how to be a “good” person – seeing the good in our students even when it was clear that the good was being swamped by the circumstances of their lives. That some of your friends inside the gaol system are now dying from this corona-virus is an indictment on so-called US-justice – and as I watch it from Australia – all the way to the very top of your federal government and the White House. I salute you and the men you serve inside the gaols and hope that their “decarceration” and safety from the virus – the chance to rebuild their lives and their communities outside comes to pass! Whatever your nation’s highest civil honour – you merit it! Jim

Thank you for sharing your experience and that of the incarcerated men in your programs. And for shining the light on the importance of decarceration and respecting all individuals and their lives.

Thanks for this great piece. As a former Chicagoan I have nothing but admiration for Henry Cervantes and his unique combination of persistence and sensitivity.

The Tree of Violence

About The Soil

It must first be said of the nature of the soil:

That the foundational principals underlying any society are like the basic elements, the soil, water and sunlight, which affect the growth of a plant.

The most fundamental of all principals, the one from which all others take root is that which addresses/defines the belief and assumption about our human nature.

How do we answer the question “Are human beings basically, that is to say, in their inherent nature GOOD. Such that we are to love our neighbor knowing that every being is worthy of our benevolence and our care.

From such a thought all virtue springs. A society of loving nurturance evolves.

Generosity and plenty (always enough to share ) are natural and abound.

Patience and compassion flourish in the golden dawn of humanity.

Where the belief is to the contrary, where beings are thought to be basically evil, greedy, selfish and so on….out of that a world of poverty, famine and war evolves.

This is the underlying “cause” of the Tree of Violence.

The societal, economic, educational, familial and ideological and altogether the environment into which people are born is largely responsible for their intellectual, physical and emotional health. This is the “Soil” where their roots seek sustenance.

The Roots

The tender sensibilities of the human heart experience the pervasive generalities of poverty, racism, violence, individualism, cynicism and competition as a traumatic threat to their very existence.

The Trunk

Profound energy oceans of fear, and anger well up and are stored and hidden away. In later life these energies lie hidden and we remain unconscious of them until they burst forth as if from nowhere. They seem to belong to our very nature. They are coupled with what are sometimes called “limiting core beliefs”. These are beliefs and attitudes about our selves, our worth and our dignity or our lack of it. There are also a host of resentments about “the way the world works”. Patterns or habits of thought and behavior are adopted

as survival techniques. These are deeply held and assumed to be simply the unquestioned truth. They become the basis for going forward and relating to life ever thereafter.

The Branches

As our arms and hands reach out to contact our world we bring with us these attitudes and the powerful energies behind them. We could say that for each arena that life presents to us we create a branch as point of contact. From this main theme a cluster of smaller branches and twigs arise. All are influenced to some degree by what is hidden in the trunk. For example themes like work, money, sex, parenting, relating to our parents, notions of family and so on.

The Buttons /The Fruit

Whenever we experience the contact with our world to be threatening, when ever it recalls or reenacts the situation of an old trauma, we tap into that trunk of hidden energy.

The power of old fear or rage comes to the surface ready to burst forth. The Tree of Violence born of violence from the roots of youthful trauma bears its terrible fruit.

The Seeds within the Fruit

If we can simply stop, just stop before the fruit has fallen. …before the word is said…before the act has happened….If we can just look at the fruit for a moment and realize that it came from our own tree, then we may look at it and appreciate it. We may be able to acknowledge its source in our own past. We can know that the cause of this emotional energy is in our own past and not from anything outside us. We may allow ourselves to genuinely feel that fruit and to know the seeds of knowledge that lie within. Those seeds have the wisdom of our pain, both now and then. And in this knowing, this pause of awareness we can know our own true nature: That we are awake and knowing; that we are kind and gentle and indeed we are strong for we have overcome a powerful urge to act with violence. We have seen through where we were blind. And in that same moment we know that all our kin, all humanity has this nature, too. Our pain and theirs become one.

There is no longer any ground to hate.

With great and boundless thanks and appreciation to Sakyong Mipham

Whose teaching inspired this prayer. Also great thanks to Fleet Maul

I work with AVP in Gardener Mass at NCCI

I have great love for the friends I. meet there and see them in the photos accompanying the article.

With love and respect for your view and your work

This is important work you are doing Henry. In a country where prisons are built based on the third grade reading scores, we seem to be preparing to incarcerate our youth rather than preparing young people to be positive leaders. Thanks for planting a seed of hope and a thought for peace in the minds of the young men in prison.