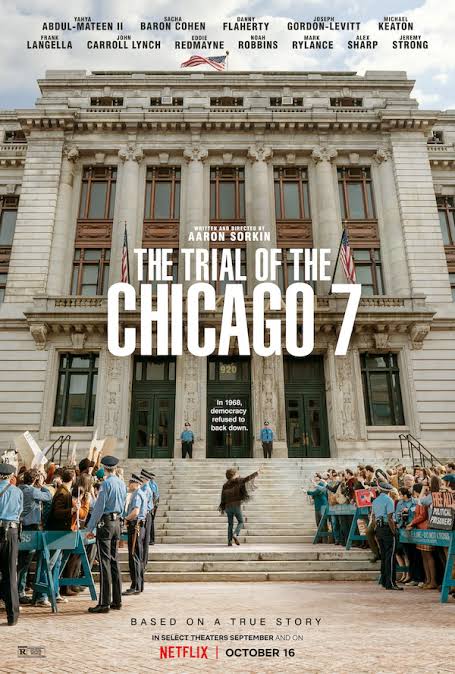

At last Hollywood has produced a film about the Vietnam War that lionizes rather than caricatures the antiwar movement. Granted, “The Trial of the Chicago 7” takes some questionable liberties with the facts — which I witnessed up close as a young antiwar organizer in Chicago at the time — but it’s not a documentary. Like other feature films based on a novel or on historical events, it shouldn’t be judged solely on its literal accuracy.

Almost every feature filmmaker wants to produce an entertaining film that appeals to a broad audience. There’s no question that writer-director Aaron Sorkin (of “The West Wing” and “A Few Good Men” fame) has achieved that objective. But “The Trial of the Chicago 7” does something much more significant. The film exposes an unjust and racist legal system, and it vindicates those who protested a senseless and immoral war. The movie concludes with a scene that can only be described as an inspiring call for resistance, perfectly attuned to a year that’s seen some of the largest street protests in American history.

“The Trial of the Chicago 7” also marks a significant departure from Hollywood’s embrace of a false narrative about the Vietnam War era — first propagated by Richard Nixon, who claimed that the antiwar movement was a bigger enemy than the Vietnamese communists. Ronald Reagan and his right-wing allies proclaimed the war a “noble cause” and turned the actual history on its head. America’s defeat was blamed on the antiwar movement and wimpy liberals who kept the United States from effectively using its firepower to turn Vietnam into a parking lot (ignoring the fact that the United States dropped more bombs on Vietnam than were dropped by all combatants in World War II). By 1991 the United States overcame what was known as the “Vietnam Syndrome,” and the country again asserted its exceptionalism — first in Iraq, then in the forever wars in Afghanistan and throughout the Middle East.

Hollywood became a willing accomplice in this effort to rewrite history. It has produced more than 100 films about the Vietnam War over the past half century, many typical war movies with heroic American GIs fighting in blood-soaked rice paddies and jungles of Southeast Asia. Others tell stories of returning vets. Several won Oscars, including “Apocalypse Now,” “The Deer Hunter,” “Platoon,” “Coming Home,” “Forrest Gump” and “Full Metal Jacket.” Yet many, if not most, Vietnam War films dehumanize the Vietnamese people, and/or show Vietnam vets as psychopaths, and/or present a grossly inaccurate view of the antiwar movement.

The supposed hostility between returning Vietnam veterans and antiwar protesters became a staple in these films. Several Hollywood films, such as the Rambo blockbusters, depicted antiwar protesters spitting in the faces of GIs at airports on their return. In “The Spitting Image,” sociologist Jerry Lembcke debunks the myth that the war’s opponents spat at returning vets. Rather than being antagonistic to war veterans, the antiwar movement welcomed tens of thousands of them into their ranks. By 1971 groups such as Vietnam Veterans Against the War became the most effective part of the opposition.

But Hollywood’s distortions stuck. In “American Reckoning,” historian Christian Appy explains the impact: “As a result, several generations of American students came of age with only the vaguest idea of why so many people had opposed the Vietnam War, and thus it became all the easier to breathe new life into the myth that the peace movement was full of self-righteous and cowardly draft dodgers.”

Previous Coverage

Ken Burns’ powerful anti-war film on Vietnam ignores the power of the anti-war movement

Ken Burns’ powerful anti-war film on Vietnam ignores the power of the anti-war movementSome fine documentary films have presented a fuller picture of the movement: “The War Within,” “Sir! No Sir! Berkeley in the Sixties,” “The Camden 28,” “The Most Dangerous Man in America” and “Hit and Stay.” (Three previous documentaries were also made about the trial, most recently “Chicago 10” in 2007). But the audience for all of these documentaries combined was probably less than the viewers of Ken Burns’ and Lynn Novick’s “The Vietnam War.” First shown on PBS in 2017, this $30 million, 18-hour PBS extravaganza reinforced the established view of the antiwar movement as an impotent sideshow.

“The Trial of the Chicago 7” humanizes the peace movement by telling the story of the most colorful courtroom drama of the era. To set the context, Sorkin begins with a sober President Lyndon Johnson announcing that he is increasing draft calls to augment the number of U.S. forces in Vietnam. Throughout the film, we are reminded repeatedly that the war is continuing, and the film ends on that note.

Within these brackets, Sorkin dramatizes the confrontation between the government (the Nixon Justice Department and Chicago Mayor Daly’s minions) and eight antiwar activists charged with conspiring to start a riot at the Democratic Party’s convention in 1968. Sorkin tells the story from the viewpoint of the defendants. But even viewers predisposed against the anti-warriors cannot help but root for them as they face the totally biased Judge Julius Hoffman. Sorkin didn’t have to embellish history to convey the unfairness of the proceedings as most of the courtroom dialogues were taken verbatim from trial transcripts.

Sorkin also didn’t exaggerate what happened to defendant Bobby Seale, then chairman of the Black Panther Party. Because of his demands to be represented by his own lawyer, Seale is gagged and chained to his chair at the defense table. It’s gut-wrenching to watch. Echoes of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin and countless others is inescapable.

Dellinger wouldn’t have supported a quasi-military organization like the Boy Scouts. And he definitely did not punch a marshal in the courtroom. He was a courageous exponent of nonviolence throughout his life.

Much of the criticism of the film revolves around its depiction of the principal characters. Since I spent the entire summer of 1968 in Chicago as an organizer, and I knew and/or worked with five of the defendants either in Chicago or in subsequent demonstrations, I certainly have opinions. Sacha Baron Cohen gives what I consider a fairly accurate portrayal of the puckish Abbie Hoffman. (I wound up in the same jail cell in Chicago as Hoffman. He had the word “Fuck” written on his forehead with which he baited the guards every time they passed by. I found it cute at first. He was probably too stoned to notice that it soon became a tiresome gag.)

I thought the film’s Jerry Rubin was mostly on target — though his supposed romance with an undercover female FBI agent is pure fantasy. The Rennie Davis character was much nerdier than the charismatic Rennie I knew. Sorkin talked with Tom Hayden at length about the film before Tom’s death in 2016. He captures that Hayden was a complex and thoughtful guy. But I recall a kind of underlying anger in Hayden’s character at the time that doesn’t show up in the movie. Perhaps another actor could have brought this out more.

Embed from Getty ImagesDespite these mostly small discrepancies, Sorkin completely missed the mark with David Dellinger. I can understand that he was trying to make Dellinger seem more sympathetic by portraying him as a suburban dad and Boy Scout leader. The truth was that Dellinger’s family — with five children — lived hand-to-mouth in an intentional community in rural New Jersey and later in a small apartment in Brooklyn. (I went to college with his eldest son, Patch; the youngest, Michele, is depicted in the movie as a boy.)

Dellinger wouldn’t have supported a quasi-military organization like the Boy Scouts. And he definitely did not punch a marshal in the courtroom. He was a courageous exponent of nonviolence throughout his life. Dellinger interposed himself between the marshals and Bobby Seale during the trial, but he definitely did not strike anyone then or any other time that I’m aware of. As I said earlier, I expect such films to alter real events to tell a dramatic story, but this scene was a travesty that made one of the most principled people I’ve ever known into a hypocrite.

It’s important to put into perspective the fact that the protests at the Democratic Convention did not have the full support of the antiwar movement, as evidenced by the poor turnout.

The movie accurately conveys the pervasive sexism of the Vietnam antiwar movement. It’s no accident that the Chicago 7 defendants and their two lawyers were white males. (Seale was ultimately severed from the case.) And the movement’s only woman character is a receptionist. In reality, women played significant roles in the defense of the Chicago 7 (including Dellinger’s daughter Natasha) as well is in the broader peace movement. Still, very few women occupied any of the key leadership positions. Many feminists cite the antiwar movement’s sexism as one of the factors that led to birth of the Women’s Liberation Movement. (Sorkin throws in a gratuitous bra burning incident during the convention, something that simply didn’t happen in Chicago.)

In one key scene, Hayden and Hoffman voice their political differences that had been simmering throughout the movie. Hayden had earlier voiced his belief that Hoffman was more concerned about publicity than ending the war. When Hoffman challenges him, Hayden doubles down by saying that 50 years from then people will remember the Hoffman and his Yippie escapades, which will make it harder for progressives to win elections that would enable them to have the power to end poverty, fight racism and militarism. Hoffman’s only comeback was that his approach was helping the defense raise money. Such an argument probably didn’t take place, certainly not as portrayed in the movie. But the tension was real between the Yippies’ guerrilla theater antics and the more conventional tactics represented by Hayden, Davis and Dellinger.

Support Us

Waging Nonviolence depends on your support. Become a sustaining member today and receive a gift of your choice, including this T-shirt!

DonateThe movie doesn’t address, however, the friction between the Chicago defendants and the broader peace movement in 1968. That is an understandable omission, as it doesn’t directly relate to the trial. Still, it’s important to put into perspective the fact that the protests at the Democratic Convention did not have the full support of the antiwar movement, as evidenced by the poor turnout — estimated to be between 5,000 and 10,000 participants (hundreds of whom were undercover agents). The previous year, two national demonstrations each attracted well over 100,000 — more than 10 to 20 times the size of the convention protest.

The defendants subsequently argued the paltry showing was due to Mayor Daly’s refusal to grant permits. That explanation doesn’t hold water since most potential attendees would not have known the details of the permit negotiations. What’s more, a year later, more than a half-million folks showed up for the Nov. 15 rally in Washington, even though the Nixon administration didn’t issue a permit until the day before the rally.

There is a big difference between wanting to have a demonstration that is “not violent” and one that is “nonviolent.”

A better explanation for the low turnout can be traced to the lack of clarity about the purpose of demonstrating at the Democratic Convention. Was it to protest the war? To support the antiwar candidates Eugene McCarthy or George McGovern? To convince the convention to adopt an antiwar plank? To express opposition to the imperialist and racist American system? These were some of the different possible objectives, and the last one was a distinctly minority view within the overall movement at the time.

An even more significant reason for the low attendance can be attributed to the provocative and/or violent rhetoric employed by organizers of the protests, which was well-known throughout the movement. Throughout the film, the prosecution points to various statements or actions by the defendants to bolster their case — Rubin showing a class of students how to make a firebomb, Hayden appearing to advocate blood flowing in the streets, the constant talk of police as “pigs,” etc.

None of this talk merited a criminal trial let alone a conviction for conspiracy to start a riot. As Hoffman repeatedly says, this is a “political trial” meant to stifle dissent. Nor should they have been convicted for precipitating any of the violent confrontations. I was there for the incident recreated in the film where demonstrators supposedly rushed the police lines. Quite the opposite happened: We all fled to avoid having our heads cracked open by the club-swinging cops. Not all succeeded, and the film correctly shows that many wound up with serious head injuries.

Previous Coverage

How anti-Vietnam War activists stopped violent protest from hijacking their movement

How anti-Vietnam War activists stopped violent protest from hijacking their movementStill, just as the violent rhetoric kept many people away from Chicago, it also gave prosecutors a lot of material to bolster their legally dubious case. Throughout the trial, various defendants insisted that they planned for peaceful, nonviolent demonstrations. That may be entirely true. But there is a big difference between wanting to have a demonstration that is “not violent” and one that is “nonviolent.” To be nonviolent, organizers must communicate clearly that violent rhetoric and retaliatory violence is not acceptable. Without such clarity, it’s difficult to recruit large numbers of people, and the wrong people (government provocateurs and those only interested in disruption) can be attracted. Second, there must be a serious attempt to make sure the tactical objectives are well-communicated and some form of discipline expected. Third, people need to understand that part of the objective of the protest is to win over others to your position.

In Chicago, we chanted “The Whole World is Watching” in response to the police riot. Unfortunately, subsequent polls showed that the vast majority of those watching sympathized with the police, not with us. And many historians believe that the Chicago riots helped elect Richard Nixon after his call for “law and order.”

It’s impossible to change the past, but we can learn lessons from history. I wonder whether it would have been possible to create street protests in Chicago like the ones King led in Birmingham five years earlier. In that campaign, people could see that the police’s use of fire hoses on children was unjustified and it exposed the violence implicit in Jim Crow. That was possible because the movement’s commitment to nonviolence provided a dramatic contrast between the demonstrators and the police.

None of these comments is meant to take anything away from the courage shown by all eight of the defendants at the trial in the face of an outrageous use of government power to intimidate lawful protest. They should be congratulated for standing up for their rights — and for the rest of us. And Aaron Sorkin should be congratulated for creating a film that lets us see how truly admirable these eight men were, as well as their lawyers and their supporters.

“Coming Home” was an anti-war film more than it was a war film. Jon Voight’s character always seemed to be based on Ron Kovic (though “Born on the 4th of July’ is more obviously about him).

Of course, it was Jane Fonda’s film, and she organized the FTA tours (though wikipedia says Howard Levy, who refused to train medics going to Vietnam, talked Jane into doing the tours.

The first “First Blood” film is violent (but I don’t remember any spitting) but I remember groups talking against it while I saw one important detail. “Rambo” was just minding his business, but the cops treated him abusively. For a lot of people on the left, their only interaction with cops is at protest. So they can react to “police brutality” but not police abuse, where people just wqlking down tge street get stopped for reasons unknown, but probably because they stand out and the cops equate that with them being ” criminal” and thus worthy of closer look. Too much of the left has been white, and thus missed a lot of detail.

Let’s not forget “Steal this Movie” which was based on part on Marty Jezer’s biography of Abbie. Marty of course was with WIN, and had some connection to the Liberation News Service, and yet also gets placed in the Yippie! camp.

Did you see the movie ‘The Strawberry Statement’ based on the autobiographical book and released at the time? It was the only thing I saw at the time that I thought expressed and matched a real emotional sense of the conflicts and ideals of those times and the people involved.

Thanks also for the first hand insightful article on the Chicago 7 that we only followed from a far distance at that time. Our father, a lawyer in our small town and deputy prosecuting attorney with mostly conservative views, seemed to follow it with interest and I’m sure recognized the injustices. And while not necessarily sympathizing with the defendants views, I think maybe he recognized their tactics. I only wish now that I knew more what he was really thinking about it. He soon had to deal with our own situation of a threatened riot in our hometown from student protestors from nearby Washington State University that winter doing the best he could to prevent provocation and overreaction from the local police department and attempting direct negotiations with the protestors.