Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part eight of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part eight of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

In the last episode, André Trocmé and his co-pastor Edouard Theis were forced to go into hiding, as an armed guerrilla force threatened the safety of the plateau and its nonviolent rescue operation. In part eight, the war comes to an end, and a spirit of revenge sweeps across France, putting André in the difficult position of trying to stave off more violence and destruction. Meanwhile, we learn the fates of Daniel Trocmé and rescue worker Madeleine Dreyfus, as well as the possible answer to one of this story’s most burning questions: Why didn’t the Nazis destroy Le Chambon, like they did with so many others who defied their will?

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 8

As much as we’ve talked about rescue in this series, I haven’t really talked much about the number of people rescued by Le Chambon and the wider plateau. But, in the opening episode, I did mention a specific number. How about I jog your memory?

Barack Obama: We also remember the number 5,000 — the number of Jews rescued by the villages [sic] of Le Chambon, France…

In case you couldn’t tell, that’s Barack Obama speaking. It was 2009, on Holocaust Remembrance Day, at a moment when he was about to give the story of Le Chambon its most high profile mention ever. There was just one problem, though: Much of what he said wasn’t exactly accurate.

Patrick Henry: We believe today that there were probably 3,500 Jews and 1,500 other people.

That’s author and Holocaust scholar Patrick Henry. And what he’s saying is that the number 5,000 is actually a better approximation of the total number of people saved by the plateau — not just Jews, but all other refugees and enemies of the Nazis. Unfortunately, however, that distinction isn’t the only thing Obama got wrong. He also said that the number 5,000 represented…

Barack Obama: one life saved for each of its 5,000 residents.

But there weren’t 5,000 people in Le Chambon.

Patrick Henry: There were only 2,500 people were living in Le Chambon. So it would be impossible for them to rescue twice their population, right?

It’s also important to remember that Le Chambon wasn’t the only village involved in the rescue operation. There were 12 other nearby villages, giving the plateau a total population of about 24,000. So, why did Obama get it all so wrong? Well, he can’t entirely be blamed.

Patrick Henry: You see, when the first figures that came out about Le Chambon, they said “Well 5,000 people saved 5,000 Jews.”

The “they” Patrick is talking about is actually a man named Oscar Rosowsky, and he said it in the 1989 documentary “Weapons of the Spirit” — a great film and still the only feature length documentary about Le Chambon. But by saying it in such an early definitive source, the notion that 5,000 people saved 5,000 Jews kind of stuck — even though Rosowsky later revised his estimate to essentially support what most accept as accurate today.

Patrick Henry: 3,500 Jews and 1,500 other people.

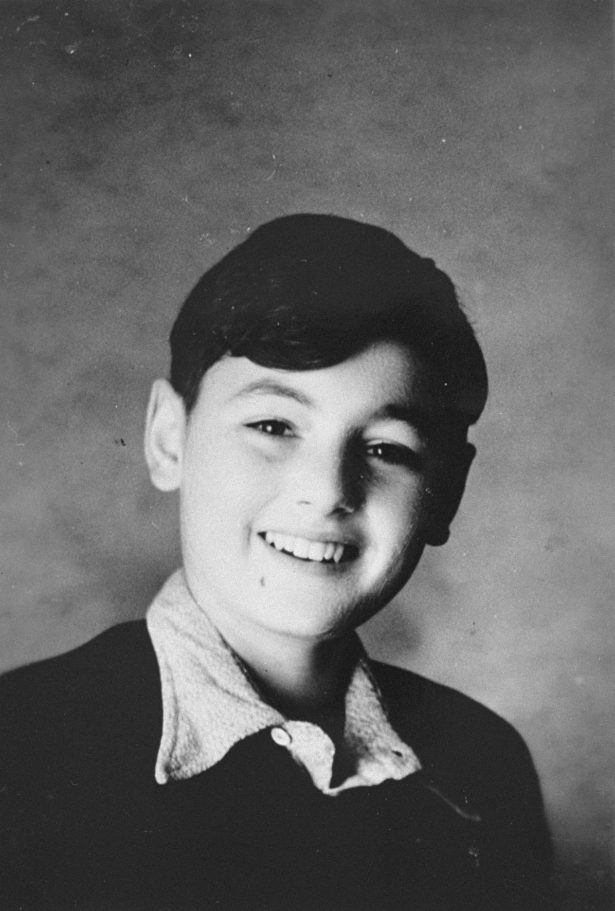

So who was this Rosowsky person, you might be wondering? And why did he know so much about how many people were saved? Well, for starters, he was one of them. He and his mother fled Germany and made it to Le Chambon when he was in his late teens. More to the point, though, he became the lead document forger on the plateau, which meant he had kept tabs on the number of people passing through who needed false papers. It’s just another one of the remarkable threads to this story.

Still, beyond the number of people saved, there are bigger questions to answer. Like why? Why were they so successful? Why didn’t the Nazis wipe them out, as they did with so many others who defied their will? I’ll try to answer those questions, and more, as we head back to France, back to Le Chambon and the plateau for the final year of the war.

—

The Allies continued their advance through France, and by the end of June 1944 things were pretty much in total chaos. Marshall Pétain was still issuing orders from Vichy, but defections were growing. Some gendarmes even joined the Resistance, which continued to harass the German troops wherever they could — not realizing how helpless they really were in the face of the massive power of the Nazis.

Amusingly, the leader of the plateau’s secret army, Pierre Fayol, actually tried to recruit outspoken pacifist André Trocmé.

André Trocmé: I refused for reasons of conscience…

But André wasn’t upset with Fayol for asking. After all, long before becoming a dedicated conscientious objector, he had once been an officer in the French Army — albeit one who refused to carry a gun.

André Trocmé: He remained our friend and often visited with us, and we both of us felt our relationship was “natural.” We both professed a moderate attitude.

The pastor and the resistance fighter were also able to agree on one important thing.

André Trocmé: I felt it was insane to attack German units because it always resulted in bloody reprisals. He agreed with me, and this probably protected Le Chambon from a destiny similar to that of several nearby villages.

One of those villages was Le Cheylard, which sat in the foothills of the plateau. As retribution for being a center of Resistance activity, the Germans decided to strafe it on July 5, which happened to be market day — so the streets were filled with all its residents. They also sent in two columns of ground troops. The first was miraculously held off by the resistance fighters, but the second pushed through and continued the assault on the already smoldering village. By the time they retreated, it had been totally devastated. There were dozens of dead civilians.

—

Le Chambon may have escaped the fate of towns like Le Cheylard, but it suffered several tragedies of its own during this period. Two of them were the direct result of resistance fighters misplacing their guns. In one case, the 15-year-old daughter of a boarding house operator was accidentally shot and killed by her friend, when the two teens found a resistance fighter’s pistol and began to play with it.

In the other case, a young doctor named Roger Le Forestier was arrested by the Germans for being found with guns in his car. They actually belonged to a couple of resistance fighters who unwittingly left them behind after the doctor had kindly — if not unwisely — given them a ride.

Nelly Hewett: He was a very adolescent-like fellow, playful fellow.

That’s Nelly Hewett, the Trocmés’ daughter. She knew Le Forestier well because he boarded with her family for a while.

Nelly Hewett: And he got involved in all sorts of things because he was the doctor of the underground, and he was the village doctor.

After his arrest, Le Forestier was brought before a military tribunal, headed by German Major Julius Schmähling.

Nelly Hewett: Schmähling, the famous Schmähling.

Now, I haven’t mentioned him yet, but Schmähling is a pretty important figure in the story of Le Chambon. He actually came on the scene at the end of 1942, when the Germans swept through southern France, dissolving the so-called “free zone.” At that point, he was the Nazi official overseeing the occupying forces in the Huate Loire region. That means, he was in charge while much of the rescue work was taking place. And knowing that, you have to wonder: What did he think of it? Surely he knew what was going on? So why didn’t he mount any serious reprisals?

Well, we’ll get into that later. For now, suffice it to say, Schmähling was no hardline Nazi ideologue. He was a 60-year-old former school teacher and army reservist, who actually opposed the Nazis for much of the 1930s — that is, until it became impossible to do so without serious repercussions. All this factored into him eventually being demoted to second in command, after the allies invaded Normandy. With the sides closing in on them, Nazi leadership wanted their most committed men in charge — and that was not Schmähling.

Nevertheless, he was still a powerful man within an absolutely evil and destructive force. When Roger Le Forestier came before Schmähling at the military tribunal, his superiors were encouraging him to administer the death penalty. But Schmähling decided to listen to the doctor first, as well as meet with his wife and other supporters, including André Trocmé. In the end, Schmähling took pity on the doctor, rendering him a more favorable punishment.

Nelly Hewett: He was told that he would be sent to Germany as a physician.

Sadly, however, that’s not what ended up happening. On his way to Germany, Le Forestier was held in a prison in Lyon.

Nelly Hewett: Headed by what they call now “The Butcher of Lyon,” Klaus Barbie.

And while there, Le Forestier became the victim of a massacre.

Nelly Hewett: Barbie took 40 people, packed them in a house or barn, and he had them shot and then doused with gasoline and burned.

It was a terrible ending for a man who had been a dedicated servant to the community and a staunch supporter of André Trocmé’s brand of Christian pacifism. But Le Forestier’s death was not without meaning, as we’ll find out later in the episode.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about the next tragedy to befall the plateau in the summer of 1944. Unlike the others, it had nothing to do with the violence that was spiraling out of control around them. It was, quite simply, the sudden and accidental death of the Magda and André Trocmé’s eldest son, 14-year-old Jean-Pierre.

One evening, he went to see the performance of a famous old French poem that described men being hung on the gallows. Jean-Pierre was a poet at heart, and the next day — it seems — he decided to act out the poem for himself. He tied a piece of cord around his neck, with the other end attached to some plumbing, high up on the bathroom wall. At some point, Jean-Pierre lost his balance, fell back and — with the noose still in place — broke his neck.

Nelly Hewett: It was definitely an accident.

That’s Nelly again. She was Jean-Pierre’s sister and the oldest of the Trocmé children.

Nelly Hewett: My parents were very very desperate after that.

Magda, quite understandably, never wrote or spoke about it, but André did and it was certainly one of his lowest points.

André Trocmé: There is nothing positive… I lost my faith, at least my faith in a God who follows me and is supposed to protect me from evil. We are all thrown into an absurd world, which is submitted to absurd and chaotic circumstances.

While André would have been devastated by the loss of any of his children, Jean-Pierre was particularly special.

Nelly Hewett: He was the most gifted and the most philosophical and the most religious.

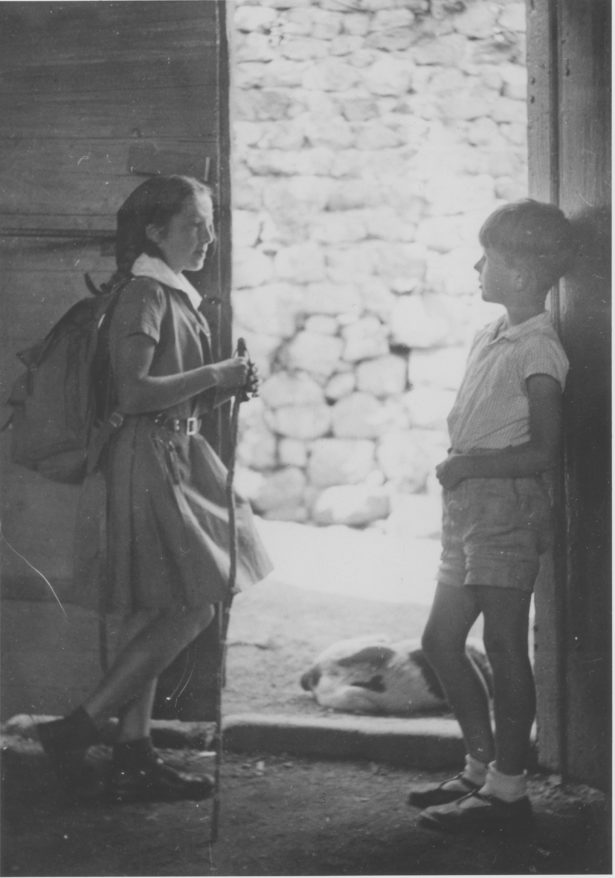

You might remember that he was the one who gave his chocolate to Mr. Steckler, the first person arrested in Le Chambon two summers earlier. He was also the one who could barely contain his anger toward the Nazis during the arrest of his cousin Daniel.

Nelly Hewett: He would have been the follower of my dad. Because of his intelligence and his sensitivity and his gifts.

It was a tremendous loss that André and Magda felt for the rest of their lives.

—

CBS News: World News Today. Supreme Allied Headquarters reports that the Americans have made a general advance on a 30-mile front in Southern France today with terrific support from the air command. There was also another bombing of the Southern French Coast, the kind that in the past has preceeded landing operations.

Just days after the Allies landed in Southern France on August 15, 1944, German forces stationed near the plateau were forced to start retreating. The resistance slowed their movement to a near standstill by blowing up bridges, blocking roads and launching some direct attacks. Eventually, the Germans were forced to surrender, which meant the Resistance now had over a hundred prisoners of war on its hands.

André Trocmé: They were taken to the outskirts of Le Chambon and put in an old mansion. And because they were in my parish, I automatically became their chaplain.

André saw this as an opportunity to intervene in a situation that was brimming with feelings of hatred and revenge. There were some who wanted to see the Germans executed.

André Trocmé: By going to visit them, I helped protect them, but it was obviously not a practice that made me popular. Still, I went.

One of the first Germans he spoke with was Major Julius Schmähling — the same Nazi official he had met when advocating for Dr. Roger Le Forestier. At this point, neither of them knew that Le Forestier had been killed. In fact, Schmähling reassured André that the doctor was in Germany, administering to the sick and wounded, and that he would soon return to France when the war was over. As the two men continued talking, André offered to lead worship services for the soldiers in German — since, after all, he spoke German fluently. Schmähling agreed and during the first sermon, André asked one of the prisoners to do a reading.

André Trocmé: I discovered later that he had been the commander of the military police and was responsible for the arrests of many Resistance members. I’m sure he would have been happy to arrest me if he had had the chance!

Resistance members were outraged at André for preaching to the Germans. So, he decided to drive his point home further by preaching the same sermon to the prisoners as he did to his regular parishioners in Le Chambon.

André Trocmé: Never had my sermons received such attention. I remember I wrote a sort of catechism, starting with the Ten Commandments and ending with justice, truth and nonviolence,

When he told it to the French, they said…

André Trocmé: “Go tell your German friends that. The Gospel is a nice theory, but with those guys, brute force is the only thing that matters.” “You’re right,” I told them. “This afternoon I am going to give the exact the same sermon to the Germans.” They had nothing more to say.

Of course, the Germans didn’t like the sermon either.

André Trocmé: “We’re not the ones you need to tell this to,” they objected. “Preach to your friends, the communists. They’re the ones who have spread the doctrine of violence throughout the world. They claim that the end justifies the means. Germans are honest people, good people, who believe in God.”

André confronted them about the recent discovery that the Germans had used gas chambers, but was told it was just “lying war propaganda.”

André Trocmé: The fact is, in times of war, the most horrible crimes are committed by the people on both sides who are the most convinced of their innocence and the unilateral guilt of their adversaries.

Of course, for the Resistance, the other side wasn’t just the Germans — it was the French people who had collaborated with them.

Magda Trocmé: People wanted to execute “traitors” — anyone who had not helped the Resistance fighters or may have denounced them.

That’s Magda.

Magda Trocmé: Just as André had been against the war between the Germans and Allies, he was against the partisan battles that were beginning. Three people in Le Chambon received a miniature coffin with a rope in it.

By speaking out against these threats of revenge, André helped the village avert more tragedy — tragedy that had become commonplace elsewhere.

Magda Trocmé: In the Chambon area, there were no executions, but in other nearby areas it was terrible.

—

There were probably only a few hundred refugees left on the plateau by September 1944. And there’s very little information available as to what happened to them. According to author Peter Grose, “Many were German, Austrian and Polish, so there was no possibility of returning to their homes.” Most eventually left for Israel, the United States, South America and other places, where they could forget the past and start a new life.

French Jews on the other hand were technically able to return to their homes — it’s just that those homes had been vandalized and there was nothing much to return to. Meanwhile, the children on the plateau had it the hardest. News had only recently broken about the existence of Nazi extermination camps. So, these children were faced with the possibility that their parents weren’t coming back for them.

BBC: I have just returned from the Belsen Concentration Camp, where for two hours I drove slowly about the place in a jeep with the chief doctor of second army.

This is the BBC’s Richard Dimbleby reporting from Germany on April 19, 1945.

BBC: I passed through the barrier and found myself in the world of a nightmare. Dead bodies, some of them in decay, lay strewn about the road and along the rutted tracks. On each side of the road were brown, wooden huts. There were faces at the windows, the bony, emaciated faces of starving women, too weak to come outside. Propping themselves against the glass to see the daylight before they died. And they were dying every hour and every minute.

By the end of the month, 9,000 people had died. Liberation simply wasn’t enough to save these people. That’s how bad conditions had been in Bergen Belsen — which wasn’t even an extermination camp. Still, it ended up claiming the lives of over 50,000 people.

Incredibly, the Jewish social worker and rescuer Madeleine Dreyfus wasn’t one of them. She had spent 11 months in Bergen-Belsen and survived. Living on starvation rations of 600-700 calories a day, her experience was one of prolonged hunger.

Patrick Henry: Imagine going through something like that and seeing people dying and figuring I’m next.

That’s Patrick Henry, who has written extensively about Madeleine Dreyfus.

Patrick Henry: She not only had letters that her son sent to me, but lectures that she gave at Sorbonne, particularly great stuff about the psychology of deported people. She was a really smart person.

In one of her writings she explained just how bad the hunger got. Here is an actor reading what she wrote.

Madeleine Dreyfus: The most important thing became finding something to eat and drink. When they brought the food, an excitement occurred that was absolutely comparable to that of animals.

At one point she actually had the opportunity to get some food…

Patrick Henry: …by making love to a guard and she told him to “fuck off.” I guess there were always those moments when you get down so low that that’s what it takes to get you back up again.

But what really kept her sane was continuing her efforts to help others. She actually led her fellow prisoners in a daily delousing session to rid them of the vermin that transmitted typhus, one of the biggest killers in the camp. And she was the one entrusted to divide up whatever morsels of food they acquired. In one instance, she had to divide a hard boiled egg into 15 slices.

Madeleine Dreyfus: I still have the taste of that 15th of the hard boiled egg in my mouth.

Patrick Henry: What a testimony to the trust that people had in her.

In the years after the war, Madeleine would often receive thanks from people who felt she had saved them in the camp — even if only by setting an example of not giving up.

Madeleine Dreyfus: I was trying to raise the morale of my companions. One is really defeated only when one willingly surrenders.

Madeleine finally returned to France on May 18, 1945 — just a couple weeks after the Allies declared victory in Europe. She wrote a rather haunting reflection around this time, juxtaposing life before and after liberation.

Madeleine Dreyfus: Spring 1945, still trapped behind these sinister barbed wires, under surveillance day and night, by these implacable watchtowers, punished, scorned, dying of hunger, of vermin, surrounded, gripped more and more tightly by an approaching Death. It wasn’t Spring. And then. Spring 1945, we finally found you, we finally met you on our way. We were miraculously transported to France. Spring, you were not an illusion; we had finally found you.

It wasn’t long after Madeleine reunited with her husband and children, that she was back working for the OSE — the Jewish relief organization she had been with with during the war.

Patrick Henry: Because after the war, there were thousands of Jewish kids they didn’t know what to do with.

The OSE had taken in hundreds of children from Buchenwald concentration camp.

Patrick Henry: The children of Buchenwald they called them. They were orphans of the war.

These were children whose parents had not returned or who did not have other family members to claim them. As a trained psychologist, Madeleine counseled these severely traumatized children — knowing first-hand what they had gone though.

Patrick Henry: Everything we know about Madeleine is that she was the same person from the time this thing happened until it was all over.

—

For the 27,000 Jewish refugees living in Switzerland, news of the war’s end was a similarly grim occasion.

Hanne Liebmann: The day it was announced I listened to the speech of King George on the radio.

King George VI: Today we give thanks to almighty God for a great deliverance…

Hanne Liebmann: It was a beautiful, sunny day. And here were the Alps in full sunshine, and I felt totally drained. It was not hooray the war is over. We had lost everyone and everything.

Hanne had been in Switzerland for a little over two years at this point and — although she was safe — life had been difficult. At first, she lived with her aunt’s family in Geneva, but that quickly became unbearable.

Hanne Liebmann: They had absolutely no understanding of what I had lived through, what I had experienced.

They were pretty well insulated by their wealth and distanced from all that had been happening in Europe.

Hanne Liebmann: Here I was, 18 years old, having experienced death many times over. And now I was supposed to live the life of the very nice bourgeois girl. Impossible.

Hanne’s aunt would constantly harass her, saying things like “What would your mother say?”

Hanne Liebmann: Well, one day I had enough of “what would my mother say” and I said, “Why don’t you leave her alone. She’s dead.” And this was the one thing really that my aunt could not admit and confront because rightfully she had to feel guilty for the loss of my mother. Simply because they had not done enough to get her out of the camp.

This experience brought Hanne to the brink of a nervous breakdown. So, she left her relatives and got a job as a maid. Of course, all this time she had been in touch with her boyfriend Max. Unlike Hanne, who had arrived in Switzerland as a legal immigrant, Max was a refugee. So, he lived in refugee housing hours away from Geneva and worked in a labor camp. But it wasn’t as bad as it sounds.

Hanne Liebmann: These were not slave labor camps. They lived like all the military did. There was never a fence, there was never anyone to say you cannot, you know, leave the house. Yeah, they had to do their work for certain hours and then they could do what they wanted.

At one point, Max was able to take some social service classes in Geneva.

Max Liebmann: I had no profession basically. So when the opportunity came to take some courses in social service, I took the opportunity. Incidentally, we also got married.

Hanne Liebmann: It was the 14th of April, 1945.

Just weeks before the end of the war.

Max Liebmann: When the war was over, that was very simple. We had nowhere to go.

Hanne Liebmann: And while the Swiss did take us in, there was always this undercurrent of resentment. We were always considered the dirty refugees.

Even though Hanne was a legal immigrant, her status had no bearing on Max. So, she was forced to join him in the refugee housing. A year later, they welcomed a daughter into the world, which only complicated matters more.

Hanne Liebmann: What should the child be? Refugee or immigrant? The Swiss government had a very great dilemma.

Children born in Switzerland were not granted birthright citizenship. And, after much deliberation, the Swiss decided she should be a refugee.

Hanne Liebmann: Does that tell you how people were harassed?

Ultimately, the Liebmanns were all but forced out of the country.

Max Liebmann: I had a cousin in Switzerland, who would have loved to have me in his factory, but we ran into so much trouble with this that we decided it’s not worth to pursue.

Hanne Liebmann: And I said, “Forget it, we go to America.” I had family here, and so we came here in March of 1948. The first day in this country was our daughter’s second birthday.

Max Liebmann: We came here with 90 dollars, and we were three people.

With help from a rabbi on the Upper West Side and the Jewish relief organization HIAS, they eventually settled into a decent life in New York City.

—

Peter Feigl arrived in New York almost two years earlier in July of 1946. He was 17 by this point.

Peter Feigl: Well, coming to New York, it was very exciting to see the Statue of Liberty, and coming into the port and into the harbor. And my uncle, my aunt, and my grandmother waited at the dock for me.

While in Switzerland, Peter had been looked after by a family who had known his father through business.

Peter Feigl: They sent me to high school. I was undisciplined at the time, created problems in school, was disruptive. After a year, the school wanted to get rid of me.

And so did the family that was caring for him.

Peter Feigl: They had had enough of me. So I was turned over to the Swiss Red Cross.

He bounced around to a few other homes and schools, until the Red Cross managed to locate his family in America. Once in New York, his rebelliousness continued.

Peter Feigl: My relatives said I had to go to school.

But first he had to pass a test covering years of American history and English, which he had never studied.

Peter Feigl: It was absolutely out of the question. I mean, I knew nothing about American history and my English was atrocious. I couldn’t have passed a two-year English test at that point.

So then his family tried to get him to learn a mechanical trade.

Peter Feigl: I didn’t want that either. I wanted to have my own money and to buy things, meet girls, take them out or what have you.

This period of rebelliousness ultimately came to an end when Peter joined the Air Force the following year. It no doubt gave him the first real stability he had had in years — since he had been separated from his parents five years earlier, never to see them again.

Peter Feigl: Through the International Red Cross I had learned back in the late ‘40s that they were transported from Drancy to Auschwitz and were immediately gassed.

None of Hanne and Max’s parents survived either. They were all killed in Auschwitz. But Max’s parents at least lived long enough to know he had made it to Switzerland.

—

Renée Kann had the rare and fortunate experience of surviving the war with her immediate family intact.

Renée Kann Silver: As soon as the war was over we went back to France, which is what I really wanted.

Life actually hadn’t been so bad in Switzerland, at least for Renée’s family. They had managed to avoid being placed in a refugee camp.

Renée Kann Silver: Miracle of miracles, really, my sister and I came down with the most virulent case of yellow jaundice, hepatitis, very very contagious.

So they were placed in a children’s hospital for nearly two months, under the care of a very sympathetic pediatrician.

Renée Kann Silver: He probably kept us there longer than necessary, knowing the situation.

This allowed Renee’s parents to rent a nearby apartment, something refugees weren’t normally allowed to do. Just as fortunately, this apartment was in a community that had formed a sort of welfare organization that provided food, clothing and other kinds of help to Renée’s family. They otherwise wouldn’t have been able to survive because Switzerland didn’t permit refugees to take jobs.

Renée Kann Silver: We had a lot of really kind help.

But once they could return to France, Renée and her family did —and they went to the same town where they had been living before the war, on the border of Germany.

Renée Kann Silver: The town had of course been totally demolished. Our apartment had been ransacked. The Germans had occupied it. Just taken all the furniture, either sold it or taken it with them or destroyed it.

Moreover, the town was pretty empty. Many people just didn’t return.

Renée Kann Silver: After the second passover, my little sister said, “Why can’t we have family like everybody else at our Seder?” And of course by that time it had become evident to us the only family we had was the family that had emigrated to the United States prior to the war or to Brazil.

So, once Renee finished school that spring, her family decided to make the move to the United States. It was July 1947.

Renée Kann Silver: I was very unhappy for quite a while, until my first year of college, when I met my husband. That was a totally unexpected event, and it just totally changed my whole attitude towards being in this country. He was a soul mate.

—

When the war came to an official end in August 1945 and all the remaining refugees and displaced people left the plateau, it must have felt quite surreal for André Trocmé. Trying to make sense of that time years later, he described it as a moment of clarity.

André Trocmé: Strangely, the war had brought us something we had been missing: By trying to save a few lives, we had finally reconciled the dream and the reality.

This dream André was referring to was the Christian dream, which — to him — meant a sort of dissolving of the ego by putting others before yourself.

André Trocmé: The truth of God is in the other, the other human being, the Jewish person we are hiding, taking some of the risk ourselves in his place.

This was something he had understood on an intellectual level, but was now truly feeling.

André Trocmé: People became so precious to me, especially my children, my wife, to whom I became attached with an immense respect.

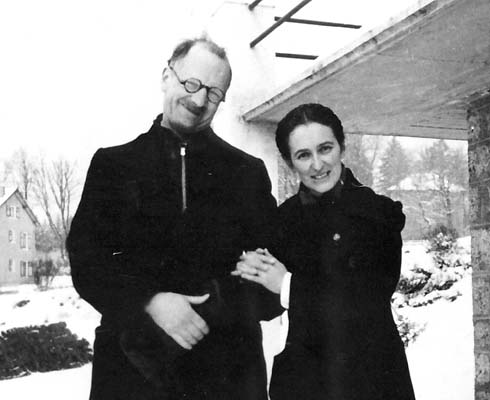

They had just been through the most difficult and productive years of their lives, and had only grown closer and more firm in their beliefs, particularly toward nonviolence. So, it’s only natural that they began looking for ways to carry that work forward in a world that badly needed healing.

When they were asked to lead the French branch of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, André and Magda jumped at the opportunity. Although it meant splitting their time between Le Chambon and Paris, they were up for the task, as it meant forwarding the important work of post-war reconciliation.

In 1947, they went to Germany, where — over the course of a month — they traveled to 35 war-ravaged cities. The destruction was overwhelming, but so was the lack of progress.

André Trocmé: It takes a few weeks in Germany and a few contacts with people of good will, on one side or the other, to become deeply discouraged. Sympathy for democracy is collapsing from one week to the next.

Hunger and ignorance were two of the main issues, and the Allies weren’t doing enough on either front to win over the hearts and minds of the German people, who were still largely under the sway of Nazi propaganda.

André Trocmé: Aside from the success of a few cultural initiatives, the Allies’ re-education efforts have failed. The only thing that would work would be to be able to invite hundreds of Germans to England, America and France — to put them in contact with good people in the west who could show them what is possible: “You see, this is what it is like when you live somewhere else. And we are not any unhappier than you are at home.”

What André was describing is — more or less — the work of reconciliation, something he firmly believed happened when people met with one-another, face to face. So, it shouldn’t be surprising that he sought out some of the Nazi POW’s he had once preached to. One of them was the prisoner he had asked to do a reading, the former captain of the military police near the plateau. This man, as it turned out, had become a conscientious objector and member of the German Fellowship of Reconciliation.

But what about Major Julius Schmähling, the official who could have made Le Chambon suffer the full force of Nazi wrath, but didn’t? Well, André eventually sought him out too. And the meeting would prove to be a decisive one for André. Incredibly, there’s actually audio of him telling the story. It’s from that same short film made in the 1950s that I featured in the very first episode — a film that might be the only recording of André talking about the rescue in Le Chambon. He begins by setting the stakes.

André (recording): You must imagine that this man, Maj. Schmähling, in 1942 or 43, that if he had caught me, would have seen as his duty to have me shot by the firing squad.

Now, incredibly, André was the one seeking him out.

André Trocmé (recording): And while I asked him, Maj. Schmähling “Could you tell me why you and your troops did not destroy the little town of Chambon-sur-lignon, where I was living, as some other German troops destroyed some of the French places where resistance against the German regime was led?” He answered, “Sir, one day our people caught as a prisoner one of the members of your church, Dr. Le Forestier.

This is the man I mentioned earlier, who was later killed in a massacre.

André Trocmé (recording): He was beaten by the Gestapo. He was badly treated. He came before me, before the military court I was presiding, with a swollen face. And while I asked him why he was resisting the orders of Hitler, he answered, ‘Sir, I am a Christian. And we are hiding and defending the Jews against you with nonviolent methods, because we believe that it is wrong for you to kill the Jews.’” And at once,” said Maj. Schmähling, “I was convinced of the sincerity of that man.”

In other words, Schmähling had come to understand the true spirit of Le Chambon. In fact, according to André — who elaborated a bit more on this story in his memoirs — Schmähling said he saw their resistance as “nothing to do with anything we could destroy with violence.” And that actually made him want to defend the village from any kind of Nazi reprisal.

André Trocmé (recording): “Later on, when, said Maj. Schmähling, we discussed in our staff if we should not undertake a repression and a killing party against your town, I always opposed any kind of violence because I knew your inspiration was Christian.”

Again, in the longer version of this story, the major told André that his advocacy for the village “cost me much, professionally and personally.”

Still, André couldn’t help but wonder why the major — who apparently had enough clout with his Nazi peers to protect Le Chambon — couldn’t stop them from killing Dr. Le Forestier. So he asked him, point blank. And the major, immediately began to cry. He apparently didn’t know that Le Forestier had been killed. And he began to explain that he had done everything he could to save the doctor.

And it’s true, commuting his death sentence and arranging for him to work in Germany — instead of being imprisoned — was no small thing. In general, the Nazis didn’t equate skilled labor with punishment. Nor were they apt to let a suspected criminal treat their soldiers. And this may be why Le Forestier was killed.

According to Schmähling, the likeliest explanation for what happened is that someone in the Gestapo attended Le Forestier’s hearing and angrily decided to arrange their own form of justice.

At this point in their conversation, André could see Schmähling was still deeply troubled to learn what had happened. So, he tried to console the major by offering him a view of the bigger picture.

André Trocmé (recording): Roger Le Forestier has died and in his death has saved thousands of Jews and true refugees, and people who didn’t want to destroy your government.

For André, this was the takeaway: Roger Le Forestier may have died tragically, but his testimony before Schmähling ultimately empowered the major to save thousands of lives.

Whether Schmähling saw it this way, we can’t know. Perhaps it’s hard to imagine that any Nazi would ever find solace in the fact that they had saved Jewish lives. But we do know that under his watch, the Haute Loire region arrested and deported far fewer Jews than the rest of France — 13 percent compared to 22 percent nationally. Even the famed Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld has spoken in Schmähling favor, saying that he and his mother hid in the Haute Loire region specifically because they had heard “the German Commander isn’t interested” in Jews.

In general, it was this reputation that spared Schmähling execution in post-war trials administered by members of the French Resistance. It was also why Schmähling felt he could return to France, to the region he once occupied in the name of the Nazis, and actually feel welcomed. In fact, some 20 years after the war, the locals presented him with a letter thanking him for easing the strain of war “within the limits of the freedom that you were granted… at a time when it was not easy to be a good German.”

None of this, of course, is to say that Schmähling should be considered a hero. It is, more simply, a suggestion that perhaps the goodness in Le Chambon brought out the best in a deeply compromised man — and that even something that seemingly trivial can save many, many lives.

—

On the next episode:

Renée Kann Silver: So I said to my husband, “You know there is a film being made about a town where I think I may have spent some time.” And he went with me, and we sit through this film, wonderful film, showing these extraordinary people, and then Pierre Sauvage speaks to a Madame Dreyfus and he said to her, “I understand you kept a little notebook.” Well, she opens this notebook on the screen and I let ou t a scream I have never in my life screamed like that. Here I saw my sister’s name and my name. That’s when I first reconnected, and the first time I realized that I had not been part of something shameful, but part of something extraordinarily beautiful.

Credits

City of Refuge was written, edited and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé were performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Madeleine Dreyfus was performed by Jasmine Faustino.

Audio of Hanne Liebmann, Max Liebmann and Peter Feigl was derived from the following interviews conducted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

- January 19, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- January 19, 1990 – Max Liebmann

- March 28, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- March 28, 1992 – Max Liebmann

- June 2, 1998 – Hanne and Max Liebmann

- August 23, 1995 – Peter Feigl

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured the following songs:

- “Quiet” by Audionautix (license)

- “Laid Back Guitars” by Kevin MacLeod (license)

- “The 49th Street Galleria” by Chris Zabriskie (license)

- “Waltz for Django” by Wall Matthews (license)

News clips came from the following sources:

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Hidden on the Mountain” – a 2007 book by Deborah Durland DeSaix and Karen Gray Ruelle

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

“Tales of Good And Evil, Help and Harm” – a 1997 book by Philip Hallie

“We Only Know Men” – a 2007 book by Patrick Henry

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

I have just come across this posting now. It was only several years ago that I became aware of the story surrounding the death of my father’s cousin Roger Le Forestier. My father was silent on this subject as he was on others related to the war.

Thank you for providing this additional history.

Janine Le Forestier