Shame, indignation and helplessness are the three words that have been heard most from the mouths of many Mexicans over the last few days. They see the elections that occurred on July 1 as dirty, corrupt, fraudulent, unfair and entirely undemocratic.

For many international elections observers as well, these elections were some of the most fraudulent they had ever seen, due to the high number of irregularities, abuses and illegalities committed before, during and after election day. But, perhaps for the first time in decades, crimes that were hidden in the shadows have now been exposed to the public light. This time, citizens’ voices have risen in unison to denounce corruption, to organize themselves and show the world that they deserve a country with true democracy, and that they are ready to fight for it.

Who led this effort? The Mexican citizens who watched over the polling stations as observers on election day, those who photographed emerging results in their districts and denounced the irregularities that they witnessed — and, of course, the Yo Soy 132 movement.

“If we don’t burn together, who will light this darkness?” is one of the expressions that best illustrates the struggle to recuperate the historical memory of the abuses committed by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) during previous administrations, and the 60,000 dead in the so-called “war on drugs” that was unleashed by president Felipe Calderón in 2006.

Since it began just two months ago, Yo Soy 132 has called for clean elections without electoral fraud and has spoken out against the media imposition of PRI candidate Enrique Peña Nieto by Mexico’s media duopoly, Televisa and TV Azteca. Their objective: to build an authentic democracy with decent, transparent news media that don’t sell themselves to the highest bidder.

In the lead-up to the elections, Yo Soy 132 worked to show the presidential candidates that the people were watching, that they would be witnesses to the elections, and that they were not willing to sit back and accept any injustice or fraud.

Today, the presumed winner of the elections is Enrique Peña Nieto. Yo Soy 132, however, doesn’t accept the election results and will contest them. On July 4, after an assembly at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) that lasted over 10 hours, members of Yo Soy 132 announced their “rejection of the process by which Enrique Peña Nieto has been imposed to take the Republic’s presidential seat.” They agreed to this statement through a consensus process, along with 118 local assemblies, and participants from more than 120 universities.

Four days after the elections, members of the movement stated that the elections “are not nor will they be accepted,” because “election day was plagued by irregularities” that they themselves documented, and they consider to be sufficient proof that the elections were undemocratic. “We reject the electoral process, which was corrupt from the beginning, with institutions that were deliberately incapable of preventing and sanctioning countless anomalies.”

They also denounced the failure to develop, on election day, “a peaceful, lawful environment, where instead profoundly antidemocratic practices prevailed, such as state violence, coercion and vote buying, profiting from the conditions and necessities of our people, media manipulation, faked polling results, and other illicit practices which altered the essence of a free, informed, reasoned and critical vote.”

In addition, the student movement declared that Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency is something that has been in the works for “many years,” with complicity from the national and foreign political-economic interests that form Mexico’s de facto government.

Lighting the darkness on the eve of the elections

On June 30, the day before the elections, Yo Soy 132 organized a massive “mega-march” in Mexico City that left from Tlatelolco Plaza (the site of the 1968 student massacre), passed in front of the TV network Televisa’s headquarters and ended at the Zócalo with unprecedented energy.

The students headed out in the early evening, just as it was starting to get dark, and they lit torches and candles while marching, illuminating the darkness by asking for clean and transparent elections. Not since the students’ march in 1968 had anything similar been seen on Mexico City’s busiest streets. The mood was different from other marches; it was much more solemn and organized. Again, the youth were accompanied by people of all ages, who followed the organizers’ instructions throughout. They seemed intent on ushering in a new era of hope and struggle, regaining the dignity of a nation that has been massacred and tortured, and is tired of feeling deceived.

The Yo Soy 132 movement put a spotlight on Mexico’s electoral process not only before the elections but also during and after. Planning ahead days before the pre-elections march, participants set up an information hub at the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City to inform citizens who wanted to know more about how they should behave at marches called by Yo Soy 132, and to invite people to observe the electoral process in every way possible.

“Remember, no money or bribe is worth the future of our country and of all Mexicans,” concludes their video, which asks citizens to watch over polling stations and report possible fraud with cameras, video cameras or cell phones and to send them to an official Yo Soy 132 email.

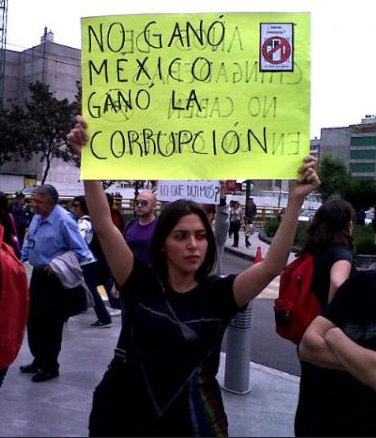

“Mexico didn’t win, corruption did”

At 11:15 p.m. on July 1, the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) released the preliminary results of the elections on national television: victory for Peña Nieto, who had between a 6 and 8 percent lead. But the Program for Preliminary Electoral Results (PREP) would continue running until 8:00 p.m. on July 2.

At 11:15 p.m. on July 1, the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) released the preliminary results of the elections on national television: victory for Peña Nieto, who had between a 6 and 8 percent lead. But the Program for Preliminary Electoral Results (PREP) would continue running until 8:00 p.m. on July 2.

Josefina Vázquez Mota, the National Action Party (PAN) candidate, recognized her defeat even before the IFE’s initial count was finalized. Felipe Calderón spoke five minutes after the preliminary results were released, designating Peña Nieto “president elect” before all of the votes had even been counted. Calderón declared that “the elections took place in a climate of peace and tranquility in most of the country,” adding that, “there have been some incidents, some of them somewhat worrying, but they have not been the rule.” Enrique Peña Nieto proclaimed himself president at 11:40 p.m. on July 1, after giving a speech in which he claimed that “Mexico won.” Most of the major newspapers and media outlets handed the PRI an undisputed victory, even though the results were not yet definitive.

For his part, the Democratic Revolution Party’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador pointed out that the election was not portrayed fairly in the media and that the constitution was violated due to the vast sums of money that the PRI spent on media coverage. He added that he would “wait until the ballot counts were finalized” on July 4 to state his position.

Hours before the first preliminary announcement, Mexican citizens gathered in front of the IFE denouncing their disenfranchisement due to a lack of ballots. “How can they be saying that Mexico has a president if I’m a Mexican citizen and they didn’t let me vote?” asked Miguel, from Playa del Carmen, around midnight in Mexico City’s Zócalo. He was unable to cast his ballot even though at 9 in the morning he had been in line to exercise his right to vote.

At the beginning of election day, many citizens went to observe the polling stations and report any type of irregularity. The Yo Soy 132 movement took on the job of compiling people’s complaints about possible electoral fraud. They have classified them into four categories: electoral crimes, polling station irregularities, use of violence and intimidation of citizen observers.

At a press conference this July 5, Yo Soy 132 showed clips of videos that show people being given prepaid cards — either 100 or 500 pesos ($10 or $50) — for supermarkets like Soriana, as well as being grouped together in trucks to vote as a bloc. By July 3, the Yo Soy 132 Observer Commission had received 1,100 reports of alleged irregularities taking place during the elections, 635 of the reports from citizens. Out of those, 325 were accusations of vote-buying, and the rest referred to irregularities at the polling stations and party propaganda being posted on the election’s eve. Most of these irregularities are blamed on the PRI.

During the evening of July 2, Yo Soy 132 held a rally to protest the fraud in Mexico City, and to express their unhappiness with the electoral process, shouting slogans against Enrique Peña Nieto. “Mexico voted and Peña didn’t win” and “Not the PRI, not the IFE, it is the people who choose” were some of the phrases being shouted on the march. The youth’s posters also criticized the media proselytizing that took place throughout the campaign.

“They can put him in Los Pinos [the presidential residence], but they will never take the power from the citizens,” read one of the posters a Yo Soy 132 protester held, while shouting angrily: “If there’s imposition, there will be revolution. Isn’t that what we said?”

What’s next?

Despite the collective depression that hit many members of Yo Soy 132 during this process, which many have called an “institutional coup,” they are combining their work as citizen watchdogs documenting fraud with resistance and spreading information. They have collected a massive trove of people’s reflections about the election that serve as a counterweight to the official discourse and the media’s powerful misinformation.

In 50 days, this youth movement has radically changed the face of a society that appeared apathetic and resigned to tolerate the normal machinations of power. While the presidency, the IFE, newspapers, TV networks and radio stations, have come together to perpetuate an anti-democratic, corrupt and authoritarian governing class that represses, manipulates and deceives, the youth of Yo Soy 132 will continue to speak out in public about the need to carve out a space for dignified democracy.

“We should continue organizing and fighting to get the country that we want, but first we must regain our dignity, become indignant, and transform this country,” said Eduardo, a UNAM student at the Yo Soy 132 camp at the Monument to the Revolution.

While the media interests ridicule it, the Yo Soy 132 movement will begin a new critical phase of transition from protest to proposal. Just as protesters suggested in their last assembly, part of their long term plan is progress on key themes such as mass media, public policy directed at the youth, human rights, culture and education. “We are going to work on these work groups for five months in order to have a living manifesto on the eve of the inauguration of the new government,” said a member of the media commission for Yo Soy 132. “We will not abandon our posture of critique, but we are entering a new phase where one of the central pillars is the construction of our proposal.”

On July 7, an international “mega-march” called by Mexican citizens took place against the imposition of Enrique Peña Nieto as president. It called for the symbolic taking of all of the public plazas in the country and all Mexican embassies on an international level. In Mexico City, more than 90,000 people marched under the slogan “No to imposition!”

The protest had three targets: Enrique Peña Nieto, the PRI candidate, the IFE (renamed the Institute for Electoral Fraud by the people for having sold out to the PRI’s interests), and Mexico’s mass media, which a significant part of Mexican society accuses of misinformation and of having supported Peña Nieto’s campaign.

Meanwhile, Yo Soy 132 held its National Summit of Students. Over the course of three days, between July 7 and July 8, participants met together in Huexca, in the state of Morelos. Students from all over the country came together to share opinions, strategies in struggle, and their impressions of the country’s current situation and of Peña Nieto’s victory. Most importantly, they traced a map of possible allies, seeking to link themselves to other social movements. (They have already managed to do so with the campesinos of Atenco and with the Union of Electrical Workers.) They want to be able to associate themselves with other social organizations and collectives in order to

extend their ties with society, creating horizontal links and mutual respect for other movements and resistances, to strengthen the relationship with civil society that is not yet organized.

The calls made by the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, or the People’s Front for the Defense of the Earth, to hold a National Convention on July 14 and 15 in San Salvador Atenco is a step toward this future union of social movements across the country. At that gathering, they must not only come to an agreement around a plan of joint action against the election of Peña Nieto, but also organize to build a more peaceful and just country. Although the meeting has not yet taken place, it is easy to draw a parallel between it and the National Democratic Convention that was celebrated in Aguascalientes, Chiapas, on August 3, 1994 with the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), during which it was said “civil resistance is the legitimate defense of the popular will in the face of government authoritarianism, in the case of electoral fraud.”

When injustice becomes law, rebellion becomes a duty. The members of Yo Soy 132 have not yet lost the battle, as many in the mainstream media insist. They are only getting started.

Resist media imposed false candidates. Write in None of the Above and modernize corrupt north American democracies. We will know a new confidence when None of the Above wins. Good alternate candidates are young enough to wait while we fix democracy now, Write in None of the Above and create real democracy now.

The question I have is, if I don’t vote for obama and write in none of the above, will that help romney? I don’t want obama but I want romney even less.

Vote for Obama . He is not perfect, but he is not corrupt. this is the most important think!Corruption destroys more than the lack of experience. I guess!!! A mexican.

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after

I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again.

Anyways, just wanted to say fantastic blog!

Everyone loves what you guys are up too. This type of clever work

and exposure! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve added you guys to my blogroll.