What can and should be done about the conflict in Israel-Palestine? Watching the news gives a highly distorted view of what is going on — with nearly all attention on violence by one or both sides, as has been the case with the recent wave of stabbings and shootings in the West Bank. For decades the conflict has regularly featured in the news, whereas many others, so-called “stealth conflicts,” are hardly ever mentioned.

What can and should be done about the conflict in Israel-Palestine? Watching the news gives a highly distorted view of what is going on — with nearly all attention on violence by one or both sides, as has been the case with the recent wave of stabbings and shootings in the West Bank. For decades the conflict has regularly featured in the news, whereas many others, so-called “stealth conflicts,” are hardly ever mentioned.

Those familiar with nonviolent action know that the struggle against Israeli oppression has involved many unarmed methods. These include the first intifada, a major unarmed uprising from 1987-1993 involving strikes, boycotts and collective organization; regular protests against Israeli expropriations, demolitions and restrictions, in many of which Palestinians are joined by Israelis and international supporters; and the 2010 Freedom Flotilla to Gaza, in which ships bringing humanitarian aid were stormed by Israeli commandoes, generating outrage internationally.

It is probably better to call the first intifada and other such Palestinian struggles unarmed rather than nonviolent. A continual feature of Palestinian resistance has been youths throwing stones at Israeli soldiers. Although stone-throwing is largely symbolic because relatively few Israeli troops are harmed, from the point of view of the Israeli public this makes the Palestinians appear to be using violence against “our” troops. Stone-throwing, from the perspective of nonviolent action, can be counterproductive because it provides justification for much greater Israeli violence. Of course, suicide bombers and rocket attacks are violent and more obviously contrary to the principles of nonviolent struggle.

If you want to learn more about Palestinian unarmed struggle, there is quite a lot of material, including Souad Dajani’s “Eyes Without Country,” Mary King’s “A Quiet Revolution,” Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta’s “Refusing to be Enemies” and Andrew Rigby’s “The First Palestinian Intifada Revisited.”

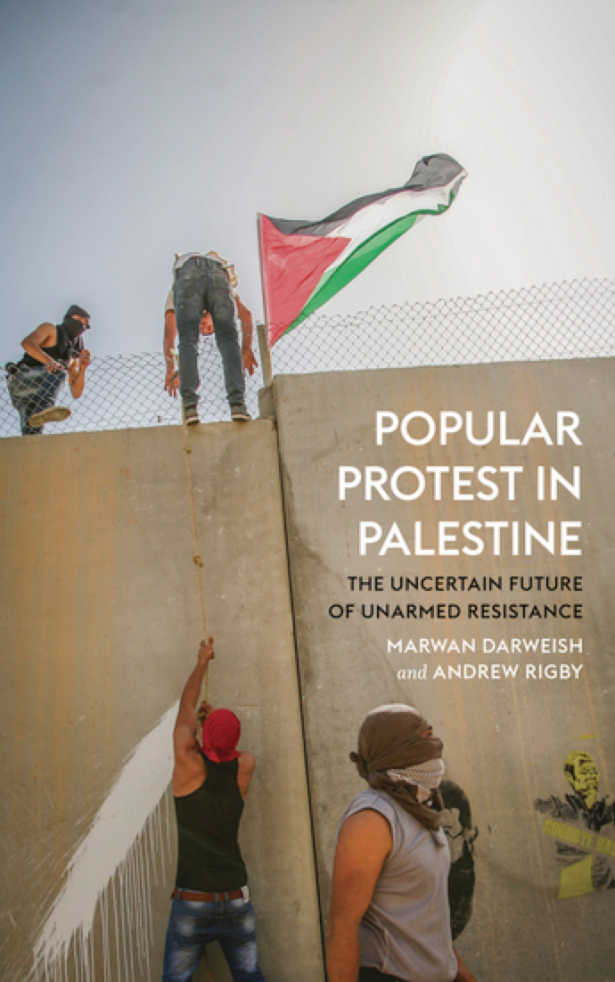

To these valuable contributions can now be added “Popular Protest in Palestine: The Uncertain Future of Unarmed Resistance” by Marwan Darweish and Andrew Rigby, the focus of attention here. The book provides a highly knowledgeable, well-written and balanced treatment of nonviolent action by and in support of Palestinian aspirations.

Darweish and Rigby carried out over a hundred interviews, most of them with Palestinian activists, asking them about their views on all aspects of the struggle, including methods, leadership, opportunities and challenges. They also interviewed Israeli activists who support the Palestinian struggle. They use this material, including many quotes, to support their overall analysis.

The conflict in Israel-Palestine is treated in the news as a set of isolated events. To better understand present actions, it is important to consider history and circumstances. Darweish and Rigby provide concise and informative coverage of Palestinian resistance to Zionism in the decades prior to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, pointing both to significant periods of protest (especially in the late 1930s) and the significant weaknesses in the resistance due to a lack of national leadership, the timidity of Palestinian elites, and an unrealistic commitment to elite-level negotiation rather than popular mobilization, among other factors. Some of the same shortcomings have persisted in subsequent decades. The authors’ examination of the struggle is a broad, analytic overview rather than a detailed descriptive account: It is especially good in giving insights into strengths and weaknesses of Palestinian resistance.

Then comes the story of resistance after Israel became a state. This includes Palestinians living in Israel, as well as those in the occupied territories. Highlights include the first intifada, the disappointments of the Oslo peace process, the second intifada (involving far more Palestinian violence and far less success in mobilizing Palestinian, Israeli and international support), the building of the separation wall and resistance to it. Darweish and Rigby offer information and insight through accounts of particular struggles (for example, communities directly affected by the wall), listing of active organizations in both Palestine and Israel, assessments of factors hindering the struggle, and quotes from activists they interviewed. All this provides exceptional insight into the struggle. For example, summarizing the situation prior to the upsurge of resistance in the period 2002–13, the authors write, “The second intifada rapidly became militarized, leaving very little space for any large-scale unarmed civil resistance. Indeed, one estimate is that only 5 percent of the Palestinian population in the OPT [occupied Palestinian territories] played any active role in resistance activities during the confrontations of this period. Some people did issue repeated calls for a turn towards civilian-based popular resistance along the lines of the first intifada, but the necessary conditions for this were no longer present.”

Their overall assessment is pessimistic. The Israeli government seems intransigent and the prospects of any progress through the so-called peace process are non-existent. Even more depressing is the state of the Palestinian resistance: for the most part, morale has plummeted and participation in wide-scale actions is limited. As one veteran of the first intifada is quoted in Darweish and Rigby’s book, “There is no unified command, no program, no real coordination between the different political forces … The 1987 intifada was a complete system, which ruled our lives. And the objective of the movement was clear. Today nobody knows what we want.” Most Palestinians focus simply on survival; activism is most developed in areas where the wall or encroachment by Israeli settlements on the West Bank directly impact local Palestinian communities. Part of the problem is dysfunction in the Palestinian leadership. Both the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza are riddled with corruption and are prone to turn on any competitors, including autonomous resistance to Israeli impositions. Palestinians are seriously divided in various ways, partly due to Israeli policies that foster divisions.

There are many non-governmental organizations operating in Palestine, providing welfare and supporting justice campaigns, but sometimes they can be part of the problem. Such a large amount of foreign money flows to these groups that they become cautious, responding to the agendas of their funders, while Palestinians are disempowered. On the other hand, internationals who join direct actions provide hope and inspiration for many Palestinian activists.

Meanwhile, within Israel, there are many solidarity groups, some taking their message to the Israeli public, others joining actions with Palestinians. However, Israeli activists have a difficult time maintaining their initiatives because so few members of the public care. The Israeli mass media seldom report on the injustices affecting Palestinians, and comments suggest that many viewers switch off when they do.

One ray of hope comes from the international solidarity movement, which has grown dramatically with the formation of the boycott, divestment and sanctions, or BDS, movement. BDS campaigners see a parallel with the international campaign that contributed to the end of apartheid in South Africa. Darweish and Rigby see the value of BDS campaigning, but give a whole series of reasons why it will be difficult to repeat the success of the anti-apartheid movement. These include lack of a unified leadership in Palestine (compared to undoubted leadership of the African National Congress in South Africa), the use of suicide bombers and rocket attacks (compared to the restraint by the African National Congress’s armed wing, which avoided attacks that might hurt civilians), and the Israeli economy’s lack of dependence on Palestinian labor (compared to the South African economy’s dependence on black labor). In total, Darweish and Rigby provide 14 comparisons between Palestine/Israel and South Africa, all suggesting that significant progress will not be as easy as in South Africa, where the struggle was long and hard.

Although “Popular Protest in Palestine” gives a pessimistic prognosis for the struggle against injustice, this should be preferred over unanchored optimism. The authors point out that there are other goals than the ending of Israeli oppression: Cultural survival and the persistence of resistance will be achievements in themselves. They cite the rise of a dissident youth voice in Gaza, condemning Hamas, Fatah, Israel and the U.N. alike, as a source of hope. That protests organized by this youth movement were obstructed by Hamas and Fatah shows the depth of the challenge facing the Palestinian people.

Eminent nonviolence scholar Gene Sharp developed a framework for a successful nonviolent struggle built around a series of stages or components: laying the groundwork, a challenge to authorities that triggers a repressive response, maintaining nonviolent discipline in the face of this response, political jiu-jitsu (in which repression backfires on the attackers), success via conversion, accommodation or nonviolent coercion, and the redistribution of power. Opponents of nonviolent campaigners can intervene at any stage to obstruct, divert or repress the challenge. Going by Darweish and Rigby’s account, the Palestinian unarmed popular resistance reached its high point in the first intifada, during which Israeli repression generated much greater support for the Palestinian cause.

Since then, things have gone backwards, and the movement is closer to the initial stage of laying the groundwork, namely building networks, understandings, skills, commitments and capacities to be able to mount an effective challenge. The Palestinian resistance has many committed members taking courageous front-line actions and persistently organizing behind the scenes. Yet, overall there is neither sufficient unity nor commitment to nonviolence to mount a challenge that can make major steps towards success. The Israeli government has developed ways of undermining the crucial preliminary stage that Sharp calls laying the groundwork.

At the end of their book, Darweish and Rigby provide a set of conditions for a “scenario of hope.” These will be difficult to satisfy. The unarmed resistance has proved incapable of generating sufficient leverage among the Israeli public or international leaders to end the occupation, and continuing violence by a few desperate Palestinians only reinforces the stereotype of Palestinians collectively as terrorists rather than victims of oppression. In this bleak time, “Popular Protest in Palestine” is vital reading for anyone who wants to understand possibilities for change and contribute to the scenario of hope.

Give credit where credit is due! Zionist movement almost a 100 years ago was the work of communist right wing religious zealots who broke away from the fundamental teachings of Torah. Zionist movement was created originally in Jewish dominated communities in Poland, Russia, Hungary that was very discreetly and tactfully introduced by the elite class of Jewish political and banking families that spread in Germany and became the cause celebre. Similarities of Zionists among those countries are very similar to the realities that today, are so prevalent in each and every Western countries particularly in USA, UK, France, Germany and rest of the Europe. Result of strong resentment by the natives of all these countries to unlimited power of the Zionists is evident as it was in Germany and rest of the Europe before the 1st and the 2nd. world war. As far as the future of helpless, poverty stricken, diseased, occupied and terrorized Palestinians is concerned, it would happen a bit more like what happened in the apartheid South Africa but lot slower as the reins of media, money and world politics is in control of the Zionists. If one reads the “Protocol of the Elders of Zion”and then reads “Oded Yinon” Project, its shocking to relate almost all of the time lined accomplishments so clearly written in the Protocol! Obviously, it is bound to become a very large scale killing and massacre of the Palestinians that would give jump start to the movement of Palestine as a country based on UN Security Council Resolutions that each and every Zionist so deeply and contemptfully detests!