After decades of organizing, pro-democracy activists in Chile are finally seeing the fruits of their labor with the release of a historical document that sets in motion the legislative process to redraft the constitution. Since 1980, when the country’s former military dictatorship established the current constitution, activists have launched dozens of campaigns, spent hundreds of hours lobbying, and rallied thousands to march. Now, with the unveiling of The Citizens Guidelines for a New Constitution on Monday, it is clear that their relentless efforts are going to set the country’s political course.

On September 11, 1973, Chile was shaken when socialist President Salvador Allende died as the air force bombed the Presidential Palace. In the context of the Cold War, the Chilean armed forces, with the support of the U.S. government, had staged a coup. These events were followed by 17 years under a military dictatorship, led by General Augusto Pinochet. During this period, the regime committed systematic human rights violations, with at least 28,000 people unlawfully imprisoned and tortured, 2,298 executed and 1,209 disappeared.

In 1980, the regime created a new constitution that continues to be the basis of the Chilean government today. Since then, the constitution has been the target of criticism and has been reformed numerous times. Marca AC recently emerged as one of the most vocal grassroots movements advocating for a new constitution. Established in 2013 with funding from a German organization, Marca AC seeks to highlight the need for a participatory democracy through the inclusion of citizens in the process for a new constitution.

One of Marca AC’s main critiques of the current constitution has been that however modified and improved it is, the constitution was established by a military dictatorship that violated the human rights of tens of thousands of people, and as such, it can never be legitimate.

Its second set of critiques focuses on the content of the constitution, which was drafted in 1980 by members of the military regime without input from opposition parties, activists or citizens. In addition, it only offers mechanisms for reforms but not mechanisms to change it entirely, leaving current governments with no “exit option.” Critics have also argued that the constitution discourages activism and dissidence.

The first push to reform the constitution came in 1989. As the military regime was voted out of power in a referendum, activists from most opposition political parties mobilized to push for substantial reforms of the constitution. These reforms were ratified in a second referendum, with over 90 percent of the votes. With these reforms, the reign of Pinochet had ended and the country launched into a new era of democracy.

However, with every subsequent government, activists have persisted in their critiques of the constitution. In an attempt to address these criticisms, each government has passed amendments, with the largest set of reforms being passed in 2005. Currently, the constitution has added more than 100 amendments.

Ironically, these reforms are now the basis for the arguments of politicians and lawyers who oppose the idea of drafting a new constitution. They argue that the 1989 referendum effectively legitimized the constitution and that the many amendments, especially those from 2005, have already so altered the constitution that it does reflect the country today. Finally, they argue that the constitution has simply been in place for so long — more than three decades — that time alone legitimizes it.

For activists and politicians, the critique persists regardless of these many modifications. “The need for a new constitution has been latent since the end of the dictatorship, as there were no changes in its design of the relations of power or a new framework to restitute social and political rights,” said Marca AC national political coordinator Manuel Lobos. “Marca AC [believes that] this change will only be superficial if it is done without popular sovereignty.”

In the 2013 presidential elections, the demand for a new constitution resurfaced with greater strength. A survey published that year revealed that 74 percent of the population was in favor of working towards a new constitution.

Marca AC became one of the most visible campaigns. Their demand was simple. Chile needs a new constitution and the best mechanism to achieve that is a Constituent Assembly. Marca AC describes a Constituent Assembly, or AC, as an institution in which “citizens democratically elect a group of representatives or delegates, who … will have it as their mission to draft a proposal for the new constitution.” This, Marca AC argues, is the mechanism that best represents the participatory democracy Chile aspires to be.

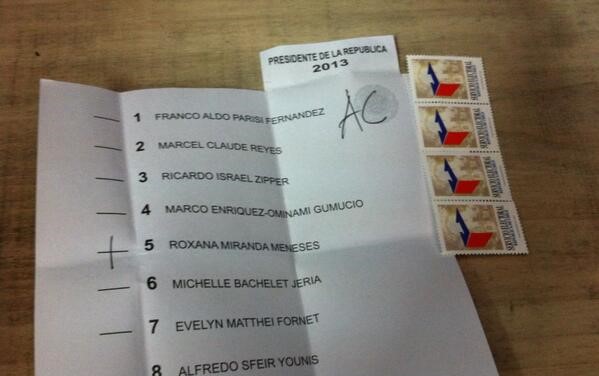

In 2013, Marca AC staged an innovative and successful campaign with the goal of raising awareness by asking people to mark their ballots with the letters AC — hence their name, which translates to Mark AC.

The campaign was a titanic undertaking. For more than eight months Marca AC recruited renowned political and cultural figures to be part of a strong social media campaign. They published videos and graphics that explained in clear terms the problems with the old constitution and their proposed solution. This brought media attention to their campaign and fueled their impact through social media.

One event in particular helped Marca AC gain momentum. In early 2013, the Servel, or Election Service, said the votes with the AC mark on them would not be counted. However, the law stated clearly that votes should be counted regardless of any markings on it. During the months that Marca AC lobbied until Servel revoked its decision, they kept an ongoing feed of their meetings on social media. This success further garnered popular support.

The message of Marca AC eventually persuaded seven of the nine presidential candidates — most importantly, Michelle Bachelet, who was elected for her second term during that election — to include in their campaign platforms the need for a new constitution. To count every “AC ballot” Marca AC recruited more than 4,000 volunteer observers to stand by the voting tables throughout the country as the votes were tallied.

“The process was intense,” said Marca AC national communications coordinator Pamela Arluciaga. “We had people in every voting center, with who we needed to be in touch constantly to make sure the votes marked were being counted. There was tension with our presence at the voting centers. In some cases there were problems with [our volunteers] wearing Marca AC pins or T-shirts, and with us just being there. There were cases in which the police kicked out [our volunteers], although we were not breaking any rule.”

Eventually, Marca AC received the final count. In the primaries of 2013, 8 percent of the ballots — or more than half a million votes — nationwide were marked AC, and in the general election, 10.3 percent of the votes were marked AC. According to Lobos, “The impact of the campaign was very strong because we were able to definitively plant the idea of a new constitution through a Constituent Assembly in the minds of the citizens.”

The impact of Marca AC, however, cannot only be measured in ballots. “[We saw] a recovery of the hope for change in people who were the tireless fighters during the dictatorship but had become disenchanted by the governments after the dictatorship,” Lobos said. “This is perhaps one of the most inspiring rewards of this process.”

A year after Bachelet took office she announced the launching of the “Constituent Process for a New Constitution.” That Bachelet has taken on this challenge has a certain poetic beauty. Her father was an air force general who was arrested, tortured and killed when he refused to join the coup in 1973. Bachelet became a vocal critic of the dictatorship and was arrested and tortured in a detention facility. Later, along with her family, she was forced into exile. Now she seeks to undo the constitution created by the same armed forces that killed her father and tortured her.

Bachelet’s “Constituent Process” consists of three stages that will span over three years, culminating in 2018. The first stage took place early this year and focused on bringing civic education into high schools and to the public.

The second stage created opportunities for individuals and organizations to draft a set of proposals for the core values, mission and institutions of the new constitution. Almost 200,000 people participated. This stage ended on January 23 with the president’s release of the Citizens’ Guidelines, which compiles the most important directions that came out of this participatory process.

An enlightening feature of the second stage is that of the total number of people who participated, 11 percent were high school students between 14 and 17 years of age. This is both a sign of the strong political participation in Chile and how much stronger civil society might become in years to come.

Dozens of organizations in every field — LGBT, women, indigenous, mental health, education and art — participated in this second stage. One of these organizations was Fundación Todo Mejora, a non-profit that works to ensure the well-being of lesbian, gay, bi and trans children and adolescents.

“We decided to participate because it is essential to be a part of something as important as the Constituent Process,” said Juan Enrique, a lawyer and current member of the board of director of Todo Mejora. “The current constitution does not specifically include the rights of children, nor does it value diversity. We believe it is fundamental that the rights of children and their right to freely self-identify are explicitly included in the new constitution. We hope the new constitution will reflect these changes.”

The final stage of the constituent process will run through 2018. During this time Congress will have to analyze the draft of the new constitution presented by the president, decide on the mechanism to change the constitution, and end with a referendum to ratify it.

During this final stage Marca AC will once again resume its efforts. The 1980 constitution still does not contain a mechanism through which to create a new constitution. In 2018, the newly elected congress will need to decide which is the most adequate. One of these mechanisms is the Constituent Assembly that Marca AC has been fighting for. In addition, there are three other possible mechanisms: a bicameral commission with members from both the lower and upper chamber; a mixed constituent convention composed of congressmen and women, as well as civil society representatives; and a referendum, which would allow citizens to choose in case congress cannot decide on one of the three mechanisms.

In 2013, political parties, politicians and organizations expressed their preference for one mechanism or the other. La Nueva Mayoría, a coalition of center-left parties, have supported the Constituent Assembly, while parties like Amplitud and independent politicians have favored the Bicameral Commission. As the 2017 election gets closer, this debate will gain momentum.

Marca AC is already mobilizing to ensure that the final decision is for the Constituent Assembly. “On August 20 we launched a campaign called ‘Candidates For AC’ to push for the local mayoral and counselors elections to be defined by their stance on the Constituent Assembly, asking our citizens to vote for those that respect their sovereignty,” Lobos said. “We will call again for people to mark they votes with AC during the 2017 presidential elections. In addition, we will reactivate the AC coalition in Congress in that key moment, as well as work throughout the country to push for a Constituent Assembly.”

The “Constituent Process” has not been free from criticism. Marca AC, along with politicians supporting their demands, has made their stance clear. Although the process claims to be participatory, in reality the Citizens’ Guidelines are only just that, guidelines. In the end, it could come down to a small group of politicians deciding what the new constitution will be. Given the corruption and ongoing scandals within the government, organizations worry that the new constitution will only reflect specific interests.

Chilean organizations still have years of work ahead of them to achieve a new constitution that will best represent Chile — more than 20 years after the end of a military dictatorship. For instance, when congress debates the final draft of the new constitution in 2018, activists will need to be there once again to bring forth the concerns of human rights organizations.

“Civil society will continue fulfilling its role to ensure the respect and inclusion of human rights in this process, supporting the state, offering new ideas, and denouncing when necessary,” Enrique said. “We will continue to be a part of this because we believe it is essential that our new constitution recognizes and values diversity.”

The history of the struggle that has led to this moment in Chile’s young history is winding and not without its setbacks. But it does shed light on one of the country’s strengths: Civil society knows that power will concede nothing without a fight. Activists have been fighting for decades and will continue to do so until they achieve what is needed — a new constitution for Chile.

People really need to get their facts straight, Allende was not killed by bombing of the building where he was, he committed suicide by a gun that was given to him by Fidel Castro, I know this as I live here in Chile.

This is encouraging news. Perhaps it will inspire efforts here for us to do something similar. What we need is a legislative branch where we are represented by vocation, not location. As it stands now, most occupations go unrepresented in our government because most of our elected officials are from one of 3 vocations: civil servants, business people, and lawyers. Thus teachers are not represented and neither are factory workers. Public transit workers are not represented and neither are nurses. We could go on and on but the point is that we need a change in the structure of our government so that more people are represented by their government.