Alice Paul returned home to the United States in 1910 to face a country torn by multiple conflicts. The decade saw whites rioting on Blacks in Georgia, Illinois, Texas, Pennsylvania and other states. Workers on strike suffered police and military violence, including the notorious massacre in Ludlow, Colorado. Anti-immigrant feeling ran high.

Justice-loving women like Alice Paul were doubly frustrated by the situation because the political system told them they had no right to intervene politically in this mess. If they worked in the mills, they should stay away from union organizers. Middle-class women were to stay home and tend to the men and children in their care. If their family was grown, those women might do a bit of charitable work. Certainly no women should have the right to vote.

Alice Paul decided to change that situation by giving leadership in a women’s suffrage movement that itself had lively disputes, including whether property destruction would be useful as a tactic to express their passion.

Thanks to the strenuous efforts by Black and white activists throughout the United States, all women in the North and white women in the South won the right to vote on August 26, 1920 with the passage of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Four and a half decades later their partial victory was completed on August 6, 1965, when Black people in the South won the right to vote.

Winning the vote with direct action

In both cases the movements hastened their victories by using a nonviolent direct action campaign — the women in Washington, D.C. and the civil rights movement in Alabama with the march from Selma to Montgomery.

By 1965 Americans were used to direct action campaigns, although they remained a controversial strategy. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was in 1955, and many campaigns in the South followed. However, prior to 1920, direct action campaigns were, aside from labor strikes, virtually unheard of.

As a young activist in the civil rights movement I knew the work of Martin Luther King, Jr., who led the 1965 Selma campaign. But I wondered who, five decades earlier, was the bold innovator who surprised America with suffrage militancy? I naturally wanted to meet the woman who’d led the struggle to victory in 1920.

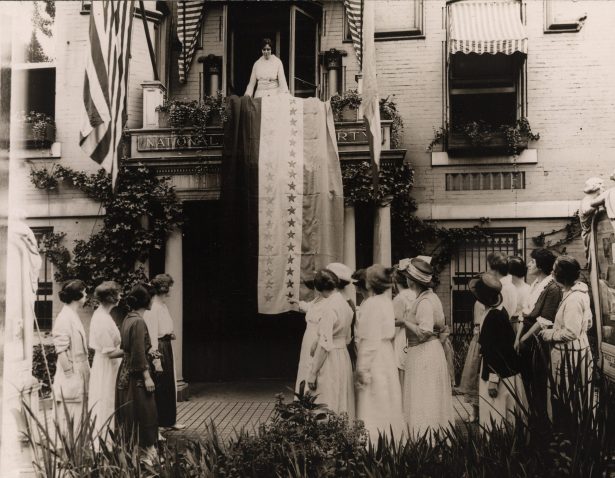

In the 1960s, Alice Paul was preoccupied with the Equal Rights Amendment, or ERA, which she launched after winning the 19th Amendment. Eventually, I landed an interview with her in 1966. We sat in comfortable chairs before a fire in the Capital Hill mansion that had long before been turned into the base of operations for the National Woman’s Party.

She started the interview by taking the offensive, which as I was to learn, was a hallmark of her strategic mind. “I’ve often thought of how differently the various species arrange the relations between the sexes. Take, for example, the praying mantis.”

I mentally gulped, catching her reference to the insect nest’s queen who has a habit of, after copulating with the male, eating his head.

I’d been put in my place.

The women’s struggle began in 1848, when a conference in Seneca Falls, New York, declared — holding its collective breath — that women should have suffrage. Frederick Douglas, the formerly-enslaved progressive leader whose understanding of liberation was extraordinarily broad for that day, urged hesitant ones at Seneca Falls to be bold. No one there could know it would take 72 years to win even a partial victory.

Previous Coverage

Alice Paul’s enduring legacy of nonviolent action

Alice Paul’s enduring legacy of nonviolent actionSetting a visionary goal is hard enough, as we see nowadays with the visions of the Movement for Black Lives and the Green New Deal. Even harder is finding the strategy that will get us there, and that’s where Alice Paul comes in.

She did her homework. While in Britain from 1907-10 studying political economy she also attended the activist school of hard knocks that was run by the Pankhurst family, whose militant women’s suffragettes were the scandal of the empire. A shy bookish young woman from a respectable Quaker family in small-town New Jersey, Alice Paul found herself in British jails three times, learning how to withstand the dreadful punishment of force-feeding while hunger striking.

She came back home in 1910 to study political science at the University of Pennsylvania, where two years later she became one of the few women in the United States to win a PhD in that field. While studying she spiced up her life with some street speaking on suffrage in downtown Philadelphia.

Facing a racist, patriarchal and huge country

Almost anyone might have warned Alice Paul that the United States would lag behind some European countries in yielding the vote to women. Then, as now, the American economic elite successfully practiced “divide and rule”: native born vs. immigrants, immigrant groups vs. each other, professional middle class vs. working class, East coast vs. the Midwest, North vs. South, urban vs. rural and, perhaps most important, white vs. Black.

Support Us

Become a sustaining member today and receive this book — or choose from one of our many other gifts. You can also make a one-time donation.

SupportAt that time the radicals’ hope of uniting all the oppressed against the economic elite was a poignant dream. On her way to her doctorate Alice Paul considered social work and spent time in a New York City settlement house working with immigrants. She saw that their oppression could only be tackled successfully by structural change — but where would the coalition come from to provide the power to win?

Each oppressed group faced the same problem, she realized: a national structure of domination. She’d been brought up by Quakers, who gave women far more respect and power than most women got at the time, and she felt all the more keenly the injustice experienced by most women. Her experience in Britain prepared her for that struggle. Why not start with one realistic empowerment step for women: the right to vote?

Deciding to win

For Alice Paul it would not be enough to witness for truth; she wanted a winning strategy. The women’s suffrage movement she observed on returning from Britain was trying to gain the right to vote state by state. Women had won in only a few states so far. A shorter route to winning, she decided, would be a federal constitutional amendment.

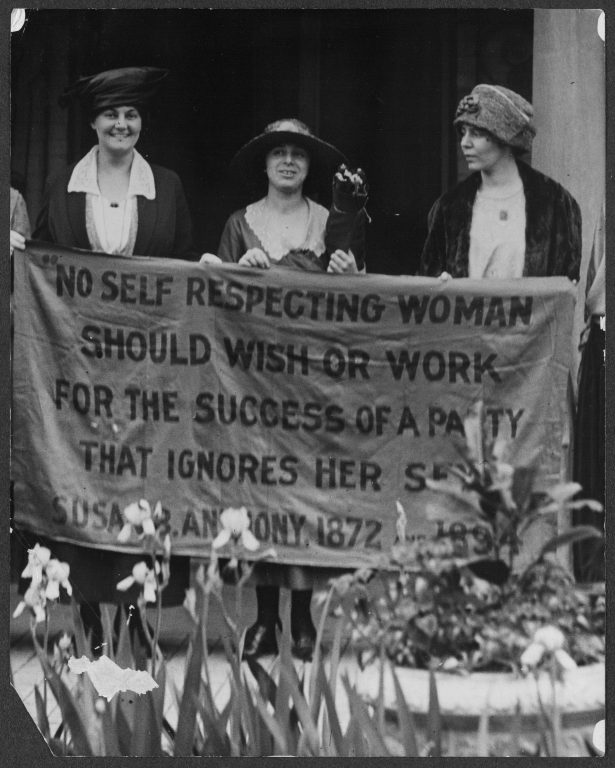

She jumped into the movement and soon came to the attention of the leadership, which allowed her to open an office on its behalf in Washington, D.C. She framed the federal amendment they would fight for, which she named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment after the most prominent women’s suffrage leader of the 19th century, who’d been arrested for voting illegally. Alice Paul also reached out to the growing Black women’s suffrage movement, led by Mary Church Terrell.

Alice Paul’s wording for the amendment was quite careful. At the time there was a welter of competing claims for attention among many oppressed groups. Mary Church Terrell was also helping to organize the NAACP, for example. In that political context the amendment was tightly focused: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

As much as she personally cared about the downtrodden on all sides — Blacks, immigrants, so many others — this campaign would focus on a single identity. It was the only way she could see to win, and most people thought even that was a pipe dream.

She knew, as did Black suffrage leaders, that even if the amendment were passed, Black women in the South would not get to vote. Southern Black men were also prevented from voting, except for a few who had not yet been stricken from the polls by the Jim Crow laws that followed Reconstruction. Suffrage for Blacks in the South was beyond imagination.

On the other hand, if the Anthony amendment passed, Black women in the North would be newly enfranchised, and that major step forward was deeply desired by the Black women’s suffrage movement itself.

There’s no doubt that racism was alive in all the progressive movements of that day. Nobody, including Alice Paul, escapes a pervasive cultural disease, and even a century later I’m not surprised to find in myself racist thoughts and reactions. In her time some of the powerful white women attracted to her campaign were explicitly racist, and it wasn’t easy for her to maintain the campaign’s unity. However, she continued to reach out to Black people and, when planning events, made sure Black leaders were visible.

Paul’s controversial use of polarization

To me the most striking aspect of Alice Paul’s strategizing was her eagerness to polarize the struggle. The patriarchy was quite clear on the woman’s role: to serve, to smooth ruffled feathers, to use the gentle arts of persuasion, and to be patient and long-suffering. The mainstream woman’s suffrage movement, while led by assertive women, was usually careful not to deviate too much from that ideal of femininity.

Previous Coverage

100 years later, lessons from the sufferin’ suffragettes

100 years later, lessons from the sufferin’ suffragettesAs a Quaker youngster, however, Alice Paul had been inspired by the stories she read about early Friends and the highly conflictual relationship they had with higher-ups in Britain — an estimated third of them were sent to jail in the 17th century. When Quakers mounted a direct action campaign for religious toleration in Puritan Massachusetts they were jailed, whipped, had their ears cropped, tongues cut out, and several were hung. (They won, by the way.)

Still, she had a shy personality and — attracted though she was to the suffrage movement in Britain — needed support first even to hand out flyers to the public and then to speak on street corners. With controversial issues, street speaking is essentially polarizing: stand on a box and take a side, and it’s likely a passerby will speak up for the other side. I’ve done this in Britain (and the United States) and it’s still true. For an activist it builds skill in bringing out and handling polarization. It rests on the assumption that democratic change isn’t possible until differences are revealed and debated.

Politicians sometimes have an interest in not revealing difference, so they can vote for vested interests without that fact being revealed or at least dwelt upon.

When Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected president in 1912 he was officially mute on women’s suffrage, but Alice Paul believed he could be the key decider on the issue. He was courteous to the women’s delegations who visited him, but she believed he was privately opposed to suffrage — or at least to doing anything about it.

Republicans in those days were more likely to vote in favor of the amendment, but the Democratic Party, with its large base in the South defending states’ rights, was divided. Because Wilson was head of the Democratic Party and had influence on its members of Congress who were on the fence, she made him — in campaign jargon — the target.

By then Alice Paul was leading a 40,000 member offshoot of the movement, the National Woman’s Party. The leadership of the mainstream movement didn’t agree with her polarizing strategy, and the disagreement led to a split.

In 1917, early in Wilson’s second term, she felt it was time to escalate with a historic first: picketing the White House. Although the public was familiar with working men picketing their factories during a strike, the women would be transgressing both class and gender codes. The women’s signs read: “Mr. President, What Will You Do for Woman Suffrage?” and “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”

Controversy grew as the vigil at the White House continued for weeks. Some of her own members and supporters withdrew from the Woman’s Party as they found their friends and relatives confronting them. Suffrage lobbyists took heat about the picketing from Congressional offices they visited.

Alice Paul maintained the weekly vigil despite the controversy. From her point of view, it was drama — stimulating newspaper coverage and discussion, and keeping the issue in the forefront of public attention. Members of the Black women’s suffrage movement, including Mary Church Terrell, participated.

War threatens to take over public space, but opens new opportunity

In the meantime, the war in Europe intensified and increasing pressure was felt within the United States to join the war. American activists of all kinds faced the choice British suffragists had faced when Britain came under threat in 1914. Most of the British suffragists put their cause on the shelf and joined the war effort. The leadership of the mainstream American suffrage movement did the same.

Alice Paul firmly refused to stand down; she went with her historic Quaker peace testimony. She also noticed that the American public was split on the war question, which opened an opportunity to increase direct action: The considerable number of anti-war women’s suffrage supporters now had no place to go except with the Woman’s Party.

Paul declared that “Now above all times, women must hold aloft the banner calling for full political liberty for all women.” At the party’s convention, a majority supported her. While some members resigned, they were far outweighed by new members. Again, I’m amazed: Despite her shy and retiring personality, Alice Paul’s formidable organizing talent, political instincts, and fierce commitment to the cause successfully rode the tiger of world-historical events.

The strategic opportunity that she saw was the increased vulnerability of Woodrow Wilson. When he declared that the aim of joining the war would be to “make the world safe for democracy,” her campaigners could focus on his hypocrisy.

That’s exactly what happened. The banners at the White House gates asked why he sent Americans to die in Europe for democracy when he denied it at home. Furious passersby began to attack the picketers, then police began to arrest the women. The women were taken to an infamous prison and placed in the worst parts, complete with cockroaches and vermin-infested food.

Half a century later, well-meaning people would strongly criticize Martin Luther King’s campaign for the polarizing impact of its nonviolent tactics. In Ava DuVernay’s riveting film “Selma,” we see the crucial confrontation of King in the Oval Office with President Lyndon B. Johnson, arguably the most powerful person in the world. Violence and killing had already hit the movement. The president tells King to stop the Selma to Montgomery march. King refuses.

In the women’s struggle, as in the Black struggle five decades later, it took strategy chops and strong nerves to stand up to the roars of dismay that “You are setting back the movement’s previous progress.” And, indeed, there are no guarantees for strategy choices — whether in electoral or in direct action campaigns.

Neither King nor Alice Paul was making a judgment call based simply on the present moment. In her case, Paul had in mind a strategy arc which she’d learned from reading early Quaker history. First, the polarization with a fading of the faint-hearted and renewed determination from others, then an uproar from the backlash, then a learning process for the fence-sitters as they watch the unfolding drama.

In Alice Paul’s day, the media environment was full of unreliable press and no television. She sent women newly released from jail on train trips to towns and cities across the country, to tell about their experiences in jail and ask for support. Local newspapers were more likely to cover those events accurately. As word got out, outraged voters wrote to their members of Congress and President Wilson urging that women should vote.

Nonviolent escalation drove the victory arc

The war-obsessed President Wilson, having run on a peace platform, then reversed himself after winning. The last thing he wanted was some other issue demanding his attention. Knowing this, Alice Paul escalated. Women brought urns with them to the White House gates to burn any of Wilson’s speeches that mentioned “freedom” or “democracy” — which would have been all of them. The women’s banners escalated, too, going so far as to call the president by the title given to the leader of Germany, a name that was especially on the lips of the patriotic Germany-haters of the day: “Kaiser Wilson.”

The response approached a near-riot day after day, and of course there were more arrests of the women.

By the time Julia Emory endured 34 arrests, Wilson moved from taking no position on suffrage, to vague approval, to (paraphrasing) “Let’s take this up after the war,” to “This is a war for democracy and we need to pass the amendment now.”

He did indeed round up enough votes to get the amendment passed in Congress. That signaled the end of the direct action campaign and motivated the national advocacy campaign that secured ratification in 1920.

Alice Paul’s boldness in escalation was born in Britain, where she was mentored by the Pankhursts, but it’s striking that when the Pankhursts turned to violence and property destruction to escalate, Alice Paul did not follow their example.

Previous Coverage

‘Suffragette’ raises question of property destruction’s effectiveness

‘Suffragette’ raises question of property destruction’s effectivenessThe results? The Pankhursts’ direct action campaign attracted many more activists than the Woman’s Party. The British also began their direct action much earlier. Still, it took them much longer to win.

The comparison suggests that using property destruction and violence, even if that approach doesn’t prevent a win, can delay it considerably. In every just cause that I know, the majority who support it would prefer to win earlier rather than later! It may be that Alice Paul, although influenced by her earlier activist training, was also influenced by her pacifism enough to escalate in a way that was strategically sound.

The cultural addiction to violence found in countries like Britain and the United States may sometimes need the antidote of pacifism to enable activists to think practically and well about how to get the job done as soon as possible.

Love this quote: “The cultural addiction to violence found in countries like Britain and the United States may sometimes need the antidote of pacifism to enable activists to think practically and well about how to get the job done as soon as possible.”

With the global uprising against racism and environmental issues, there is more openness now to turning away from violence as well.