[Listen to this bonus “City of Refuge” episode or read the following article adapted from the transcript.]

As the world shuts down amid this terrifying pandemic, it’s hard to know what to do — or, just simply, how to be. I’ve tried reading news story after news story and scrolling endlessly through Twitter, but neither have left me feeling any more enlightened.

The only thing that’s proven helpful thus far is a 73-year-old novel that’s been on my reading list for several years now: Albert Camus’ “The Plague.”

Although written during World War II — and intended as an allegory for the Nazi occupation of France — this classic novel feels immediately relevant. A disease that spreads from animals to humans wreaks havoc on an unprepared population, one that is too wrapped up in itself and its economic dealings to take the threat seriously at first. Meanwhile, self-interested politicians delay making important decisions. Eventually, when denial no longer works, there are quarantines, supply shortages, fake remedies, issues with masks and, of course, mounting deaths. If not for the fact that the plague only ravishes a single town — instead of the entire world — it would seem almost perfectly prescient.

Nevertheless, the novel resonates in other ways, such as with its theme of exile and isolation. Camus actually introduces it even before the plague arrives, as a comment on modern life in general. The quarantines only make this sense of isolation more acute — something that no doubt feels familiar and will only sink in further once we are fully bored with streaming movies and video chats.

Ultimately, as the novel unfolds, Camus shows us that it’s possible to break out of this depression — even in a moment of crisis — by depicting a kind of active resistance to the plague that fosters solidarity and compassion, with a focus on saving lives.

While I’m far from the first to find this classic so insightful and relevant in our current moment of crisis, I doubt few have had it near the top of their reading list for as long as me. The reason for that is my recently completed 10-part podcast series “City of Refuge,” which tells the little-known story of a cluster of French villages on a remote plateau that rescued 5,000 refugees during World War II.

All throughout my research, Albert Camus and “The Plague” kept popping up. It was mainly as just a side note, because, as it happens, the famous French-Algerian author wrote much of the novel while living on the plateau in one of those courageous villages. He was, in essence, completely surrounded by people doing everything they could to save the lives of those in need.

I was never quite sure how, or whether, to mention this interesting fact in my series. And now I’m glad I didn’t merely mention it, because it’s deserving of a deeper dive. So, what follows is an examination of Albert Camus’ “The Plague” and the real-life nonviolent history that helped shape its timely, and timeless, message.

Trapped ‘like rats!’

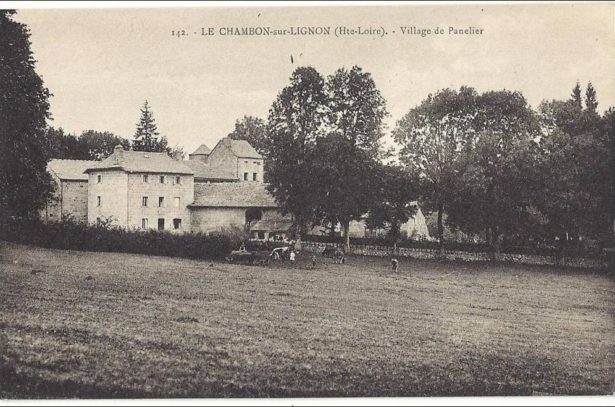

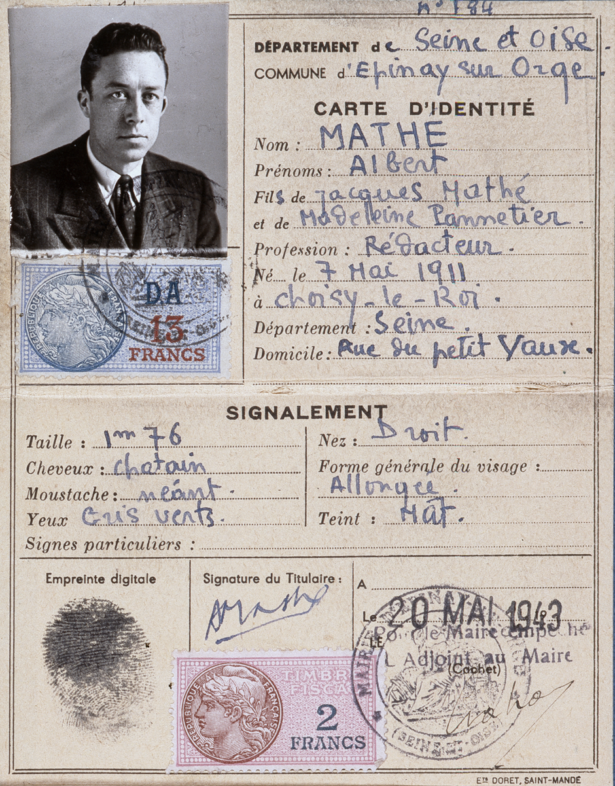

Albert Camus left his native Algeria in the summer of 1943 with the plan of spending the winter in the mountains of France. He had contracted tuberculosis in both of his lungs, and his doctor prescribed the fresh air as part of his treatment. Camus’ wife, Francine, knew of the perfect place — a quiet, sparsely populated plateau in south-central France, where she had often vacationed as a child.

Once they were settled into a boarding house — only two miles from the village of Le Chambon, the center of the plateau’s nonviolent resistance — Camus and his wife enjoyed the rest of their summer together. Then, in the fall, Francine returned to her teaching position in Algeria. Camus soon decided to join her, as the war was worsening and getting home seemed like a good idea. But just as he had made plans to hop a steamer back to Algeria, the Allies invaded North Africa.

It was November 7, 1942, and with the Nazis quickly responding to the invasion by occupying Southern France, Camus was now trapped. Days later, in his notebook, he drove the point home further, writing down the phrase “Like rats!”

Camus’ plague was a stand-in for more than fascism. It was also a symbol for what he considered to be, more broadly, our culture of death.

It isn’t surprising he made this analogy. Rats were on his mind a lot in those days. They were the harbinger of death in the novel he had begun working on a year earlier — a novel that would, of course, become the acclaimed “La Peste” or “The Plague.” At this early stage, however, Camus was far from settled on a title. Not only did most of the work lie ahead of him, but the next 14-15 months he would spend on the plateau — exposed to its unique culture of resistance and rescue — would have a serious impact on the novel. Surprisingly, this fact isn’t widely discussed.

“Many of the biographers assumed that Camus didn’t know anything about what was going on on the plateau,” said Patrick Henry, author of “We Only Know Men,” the first book to truly explore Camus’ time on the plateau. “[They] never did their homework.”

In other words, Camus’ biographers weren’t in contact with the plateau’s local historians and researchers to the degree that Henry was. In fact, it was thanks to one of those contacts that he was able to interview an old friend of Camus’ — a Jewish French Algerian named André Chouraqui, who lived on the plateau during the war.

“Camus used to go to his house, and they would eat Algerian food and talk,” Henry said. “He was a specialist on the Bible, and he talked to Camus about the plague and the significance of the plague in the Hebrew Bible.”

Importantly, Chouraqui did clandestine work for the Jewish relief organization Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants, or OSE. “City of Refuge” listeners will recognize it as the organization Jewish rescuer Madeleine Dreyfus worked with. In fact, after she was arrested, it was Chouraqui who took over her duties of bringing refugee children to the plateau and hiding them. Learning this naturally made Henry wonder how much Camus knew about the rescue operation being conducted on the plateau.

“André Chouraqui wrote and told me, ‘Of course Camus knew everything that was going on,’” Henry explained. In fact, it would have been hard for him to miss — as, according to Henry, “There were actually Jews living in the same boarding house where Camus was living.”

Given how ubiquitous the rescue operation was on the plateau by this point, the next obvious question was whether or not Camus knew André Trocmé, the plateau’s charismatic pastor who lived in Le Chambon and was one of the driving forces behind the rescue effort.

Chouraqui told Henry that “Albert Camus had always known about the resistance that Pastors [Edouard] Theis and Trocmé conducted in Le Chambon,” but wasn’t sure Camus knew André Trocmé personally.

Nelly Hewett, André Trocmé’s daughter, confirmed this when I spoke to her. She said that although her parents never met Camus, “They knew of Chouraqui and he knew of them.” She also mentioned Pierre Fayol, the Jewish leader of the plateau’s armed resistance.

“They all were friends those guys. Fayol visited with my dad. Chouraqui visited with my dad. They had an inner group of which my dad was not a part. But they respected my dad’s work.”

In ‘The Plague’ resistance is depicted through what are called ‘sanitary squads,’ a sort of civilian-based defense against the death-dealing pathogen.

Henry did some more digging and found that Fayol mentioned Camus in his memoir several times, noting that they often listened to the BBC together. This meant that Camus was plugged into all aspects of resistance on the plateau. That said, it’s important to note that resistance armies didn’t start popping up in France until around the time Camus arrived on the plateau, about midway through the war. The nonviolent resistance in Le Chambon and the surrounding area, on the other hand, had been going on for a couple of years already. Nevertheless, Fayol was respectful of its mission.

“On the plateau, there was very little killing going on,” Henry said. “Trocmé and Fayol were working together because they knew that, if they attacked, the Germans would bomb the place or kill people and the whole rescue mission would be destroyed. There wasn’t a great question of violence on the plateau.”

‘A greatness that I don’t have’

Realizing that Camus was apprised of these goings on, Henry began to see “The Plague” in a new light.

“Once I got that, it was like the key to the novel,” he said. “Let me read the novel now with everything I know about Le Chambon, and see what connections I can make.”

For starters, at just the surface level, there was the obvious allegory to the Occupation.

“In France the Germans were considered like a plague,” Henry explained, adding that they were called “la peste brune,” or “the brown plague,” because of their brown uniforms.

Although the idea of the allegory is well-established, it’s not always been appreciated by critics. Jean-Paul Sartre and other French thinkers were upset with Camus for comparing Nazism to a nonhuman phenomenon that was unrelated to human evil and therefore out of our control. But Camus’ plague was a stand-in for more than fascism. It was also a symbol for what he considered to be, more broadly, our culture of death — which he saw on all sides of the political spectrum, from the wealthy conservative establishment to the revolutionary dictatorships of the left. As a result, existential Marxists like Sartre were already primed to take issue with Camus and his novel. According to Henry, Sartre’s magazine Les Temps Modernes called it “boy scout morality” — really denigrating it in the worst way.

While the Marxists saw Camus as a pacifist, his actual views were a bit more complicated. We’ll explore that more momentarily. But first, let’s continue to examine the other connections between “The Plague” and the plateau — namely how some of the characters in the book resemble real people Camus knew or heard about.

One such character is Joseph Grand, a sort of secondary character who the narrator at one point refers to as the hero. But that comes with a bit of a qualification. Since Camus didn’t find the concept of heroism appealing, he has his narrator say that if there were a hero, it would be Grand because he’s just an ordinary man who did the right thing without thinking about it or seeking recognition.

“That’s the guy who is living right next to Camus,” Henry noted, referring to a scene in the 1989 documentary “Weapons of the Spirit,” where Director Pierre Sauvage interviews Camus’ real-life neighbor on the plateau, a man named Émile Grand. Whether the character in the novel is meant to be him it’s hard to say. More broadly, the Grand character seems to be a strong representation of the plateau’s rescuers at large. As André Trocmé’s wife, Magda, once said, “None of us thought that we were heroes. We were just people trying to do our best.”

In “The Plague” resistance is depicted through what are called “sanitary squads,” a sort of civilian-based defense against the death-dealing pathogen. Notably, they are created and organized by a rather idiosyncratic pacifist character named Jean Tarrou, who shares a few commonalities with Camus himself — aside from his rhyming last name.

“Camus was against killing,” Henry explained. “He waged war against the death penalty in France. His father saw an execution and came home and vomited. Camus heard the story about his father, and he tells the it in ‘The Plague.’”

More specifically, the character of Tarrou tells it. Only, instead of Tarrou’s father witnessing the execution, his father is actually the prosecutor demanding the death penalty. Tarrou explains that he saw his father’s state-sanctioned blood lust and decided to run away. At first, he joins various leftist struggles against oppression. Eventually, though, he comes to the realization that because these struggles sometimes involved killing to achieve their means he was fighting against an unjust system without bringing a just one into existence. Because of this, Tarrou says, “I had the plague already, long before I came to this town.” In short, he’s noting Camus’ broader use of the plague as a metaphor for humanity’s self-destructive qualities.

As Camus saw it, there is only one thing you can do with this knowledge: Become what he called “a rebel,” or someone who stands up for life and solidarity. In the novel, Tarrou explains his philosophy by saying, “There are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.”

For this reason, Henry describes Tarrou as “the ideal total nonviolent person.”

At one point in the novel, Tarrou lays out his basic formulation on pacifism, saying, “I decided to reject everything which directly or indirectly, for good reasons or for bad, kills. I definitely refuse to kill.”

Camus even tried to help hide a Jewish woman he met, writing a letter to Pierre Fayol back on the plateau saying, ‘I’m sending someone to you who has a hereditary infection.’

It’s such a perfectly stated position on pacifism, and yet Camus himself was not an absolute pacifist. For all the nonviolence imagery in the novel, Camus saw violence as both “unavoidable and unjustifiable.” In fact, while writing to a friend nearly a decade after the war, he said: “I studied the theory of nonviolence, and I’m not far from concluding that it represents a truth worthy of being taught by example, but to do so one would need a greatness that I don’t have.”

However, Camus does let his character Tarrou have it.

“Tarrou has the greatness, and it links to Trocmé, who believes that one must resist violence but only with ‘the weapons of the spirit,’” Henry said.

At the same time, however, Tarrou has key differences with André Trocmé — namely religion. Tarrou says he wants to become a saint without God. But André Trocmé, a Protestant minister, was absolutely a man of God. Interestingly, though, his wife Magda was not religious and therefore, in many ways, embodied this idea of a secular saint.

“Mother always said that she really didn’t believe in God — the God that was usually a ‘He’ and was the head of the world and solving the problems,” Hewitt said. “But she had everything else that made her a Christian. All the qualities, all the generosity.”

So, if Tarrou was a match for anyone on the plateau at that time, it was almost certainly Magda Trocmé. That said, as I mentioned earlier, the Tarrou character is closer to Camus himself than any other real person.

According to the acclaimed theologian and writer Thomas Merton, Camus had a hard time accepting nonviolence because of how much he associated it with Christianity, which he largely rejected and saw as pushing a kind of self-interested do-nothing nonviolence. This is unfortunate, Merton argues, because it led Camus to overlook authentic nonviolence, which in many ways mirrors the kind of active resistance he clearly admired.

Ultimately, in Merton’s assessment, Camus didn’t like to offer precise doctrines or absolute formulas. He was quite reasonably — like any activist today — not wanting to preach or prescribe from a position of privilege. So, according to Merton, “at the risk of seeming inconclusive,” Camus “does not prescribe a method or tactic.”

Nevertheless, it’s not hard to read between the lines of “The Plague” and see what kind of resistance Camus is getting at.

“Camus is recognizing the nonviolent struggle for saving human lives,” Henry said. “Stopping people from getting infected, etc.”

In fact, the one instance of “revolutionary violence” that appears in the novel fails to achieve anything. It happens when a few armed men attack the gates of the town, trying to break out. They exchange fire with security forces, leading to a few deaths. This only really succeeds in sparking a wave of looting, that in turn led to martial law and executions. But, as Camus notes, there were so many deaths from the plague at this point, nobody cared — they were “a mere drop in the ocean.”

This isn’t to say Camus isn’t sympathetic to the stress and anxiety that led to the violence and lawlessness. We relate to one of his characters, a journalist named Raymond Rambert, who — like Camus — is an outsider, trapped in this place and separated from his wife. Rambert tries to escape by securing clearance papers through an illicit underground network. But along the way he has a change of heart and decides to stay, joining the sanitary squads and aiding the struggle to defeat the plague.

“That’s what happened to Camus,” Henry explained. “He tried to get out, and then he didn’t go out. And just like the character in the novel, he believes that he belongs there. And it is his duty to be part of the Resistance.”

In the fall of 1943, after more than a year on the plateau — witnessing active resistance to the Nazi agenda — Camus moved to Paris, where he became co-editor of Combat, the underground resistance newspaper. Even then, however, rescue work remained on his mind. He even tried to help hide a Jewish woman he met by writing a letter to Pierre Fayol back on the plateau saying “I’m sending someone to you who has a hereditary infection.”

“Camus knew what was happening,” Henry said. “He was sending a Jew to be protected there in Le Chambon.”

‘Fashion an art of living in times of catastrophe’

There’s one last character in “The Plague” worth exploring, and he’s probably the most important, as he’s also the novel’s narrator. His name is Bernard Rieux, and he is the town’s doctor. (Incidentally, there was a similarly named real-life Dr. Riou in Le Chambon during that time.) He is in many ways a different side of the same coin as Tarrou.

When Tarrou says he wants to become “a saint without God,” Rieux says he just wants “to be a man.” Tarrou then responds by saying, “Yes, we’re both after the same thing, but I’m less ambitious.” It’s a rather telling bit of self-deprecating humor through which Camus is letting us know that Tarrou’s pursuit of secular sainthood and Rieux’s pursuit of being a decent person are basically the same thing.

Camus wanted people to ‘fashion an art of living in times of catastrophe, to be reborn by fighting openly against the death instinct at work in our society.’

However, if there is a difference in the labels, it could be argued that by the end of the novel, it is Tarrou who becomes a man and Dr. Rieux who becomes a “saint without God.” Whereas Tarrou gets out of his head a bit and starts living not as an outsider, but in solidarity with his fellow citizens, Dr. Rieux is tested and never comes up short. He just continues to cure the sick and relieve human suffering. Notably, he is a healer, a term that Tarrou seems to equate with the saints. Most importantly, though, both characters have no desire to prove anything — and this is the quality that ties them back to the people of the plateau.

“Weapons of the Spirit” Director Pierre Sauvage underscored this connection in his film, noting this passage from the novel: “For those of our townspeople who were then risking their lives, the decision they had to make was simply whether or not they were in the midst of a plague and whether or not it was necessary to struggle against it. The essential thing was to save the largest number of people from dying. The only way to do this was to fight the plague. There was nothing admirable about this attitude. It was merely logical.”

Ultimately, it’s the message of “The Plague” — not the characters or the type of resistance depicted — that’s in sync with what happened on the plateau during the war. When accepting the Nobel Prize for literature in 1957, a decade after “The Plague” came out, Camus essentially summed up that message, saying, he wanted people to “fashion an art of living in times of catastrophe, to be reborn by fighting openly against the death instinct at work in our society.”

Camus himself, however, did not live much longer. It was only a few years later, in 1960, that he died in a car crash at the age of 47. Despite having accomplished so much at a relatively young age, there are those who think even bigger things were in the works.

“Camus was going somewhere,” Henry said. “Some say Camus was on the road to a religious conversion, but it could have been a conversion to something where he would be able to accept total nonviolence.”

This is not hard to imagine. After all, as Merton noted, Camus oftentimes spoke like a pacifist and, in practice, came very close to the nonviolent position. Much like ardent pacifist André Trocmé, Camus spoke out against revenge killings after the Germans had been defeated. He also was one of the first to condemn the bombing of Hiroshima, calling it “the ultimate phase of barbarism” in human history.

‘When you leave it at the level of the microbe, it’s not complicated today. We don’t have to kill anybody. We have to remain decent.’

Whether or not he was headed toward some kind of personal conversion to total nonviolence isn’t really the point. It merely underscores that Camus was one of the few leading international voices of his time willing to consider its merits. In fact, he reportedly attended a conference on peace and peacemaking in Le Chambon shortly after the war. It was organized by none other than André Trocmé and attended by pacifist leaders from around the world.

According to Henry, “He was sitting in the back of the room and made some remark about people getting together to talk about these things is wonderful.”

Ultimately, what drew Camus to nonviolence — at least the kind practiced on the plateau during the war — is the focus on saving, not harming, lives.

“On the plateau he recognizes that nonviolence is a great way of saving Jews,” Henry said. “The Jews that were saved during the Holocaust were not saved by confronting the Nazis with violence. They always got killed when they did that. They couldn’t defeat this machine.”

In short, Camus saw something special happening on this tiny, isolated plateau where he was stuck for part of the war, and he drew inspiration from it to produce a singular work of art that offers empowering lessons on how to act in moments of crisis. Viewed from our current position, in the middle of this pandemic, it’s quite simple.

“When you leave it at the level of the microbe, it’s not complicated today,” Henry said. “We don’t have to kill anybody. We have to remain decent.”

Even then, however, the plague is never fully defeated. As Camus’ character Dr. Rieux notes on the final page of the novel, after the city overcomes the outbreak, “The plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good.” It lies dormant, until the day it rouses up its rats again and sends them forth to die in some unsuspecting place.

For that reason, we must never forget how to fight it — whether it comes in the form of a pathogen, fascism or some other cynical, destructive force. As the stories of the plateau and “The Plague” tell us, we are going to need solidarity, compassion and a steadfast commitment to saving lives.

In the words of Camus, “What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves.”

This is a wonderful story, told beautifully. I’m so happy to learn so much about Camus the person.

Thank you and God bless you.

Peace,

Molly Rush

Did not know the details in your piece about Camus and Trocme’s paths crossing at least a bit. Thanks for sharing that. Can not help bit wonder what great good would have come from a collaboration.

The Plague, and Lest Innocent Blood be Spent, and Neither Victim nor Executioner and Trocme’s call for Jubilee are annual reads.

We work on gun laws that either never become laws or get so diluted they don’t save lives. Many people focus on gun laws to end violence. I have a difficult time getting groups to see a larger picture of a violent society…what are the causes? Many. Once we name them we can work at the root of the problem and get rid of the seeds of violence. We don’t have to kill anybody. We just have to remain decent. Talk about the damage violent movies do and get a gleeful response that everyone has evil in them. Try to discuss that the movies teach violence as a solution to the very young and it feels like many have been so brain washed, they truly believe non-violence is impossible. Some solutions: I worked in the SF DA’s Restorative Justice program in Neighborhood Courts listening to people who had committed misdemeanors and helping them to find alternatives by healing the harm; we had rehab programs, a program for shoplifters, and one for Johns and gamblers. We always asked if they were sorry? saw the harm they had caused? wanted to write an apology letter? The results were amazing. On Nextdoor social media, many rant against the homeless and want them moved out of their neighborhood. When just one person talks about giving out hard boiled eggs or hot soup, others begin to add their own non-violent resistance and the hateful language and unsubstantiated claims begin to fade….thank-you.

Matéria que nos incentiva a não desistir das vidas, apesar das tantas que perdemos.