Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part 10 of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above.

This is part 10 of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above.

In the last episode, we heard how the story of the plateau’s heroic nonviolent resistance and rescue operation was kept alive in the years after the war. In part 10, we examine its significance today, as the world faces similar crises, and ask: Is nonviolence an effective method for resisting genocide? How can we follow in the footsteps of these World War II rescuers?

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used in this episode, as well as acknowledgements to all who helped in the making of this series.

Part 10

It was just a letter, a simple angry letter from someone who hadn’t even read his book. But that’s all it took to tear Philip Hallie down from the high he had experienced while researching and writing about Le Chambon.

Philip Hallie: So I wrote “Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed,” and became converted, a different person of sorts, for a while.

The letter, which came from a man who had only read a magazine review of the book, told Hallie that he was wrong, that nothing of importance had happened in Le Chambon. It was just a bunch of eccentrics helping a few refugees — and that’s not the sort of thing that shapes history. Only great armies do that, the letter explained.

Hallie began composing a response in his head, asking the man: “How was saving thousands of people’s lives nothing? How was having the courage and the will to shelter all those people for four years while under Nazi occupation, nothing?”

But he never got these questions down on paper. Somewhere in the midst of thinking through his response, he began to doubt his own words. That’s when he said to himself…

Philip Hallie: “Wait a minute, wait a minute. Something in your heart resents the village. Something in your heart resents the village.”

As more time passed, Hallie’s feelings of resentment toward the village grew even stronger. They didn’t have to do the things he did — or see the things he saw — as a combat artilleryman, tasked with laying waste to German cities.

Philip Hallie: I saw people burning. I saw heads, or an arm, just lying there in the road.

And yet, despite believing such things to be despicable, Hallie felt what he and the Allies had done was necessary.

Philip Hallie: It took decent murderers like me to stop Hitler. Murderers who had compunctions, but who murdered nonetheless.

And if the circumstances were similar, he said…

Philip Hallie: I wouldn’t hesitate to do it again.

So, what does it mean that the man who put this remarkable story of nonviolence on the map no longer found it inspiring? Does that lend greater credence to the naysayers — people like the person who wrote Hallie that letter? Should we dismiss the hope that Le Chambon represents: that we, ordinary people, have the ability to confront and even stop the evil we see in our world?

As much as we’ve been focused on the particulars in this story, we haven’t done much analyzing. So, in this final episode of City of Refuge, that’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to get to the bottom of what this story really means, and how its lessons can help us confront some of the crises we face today.

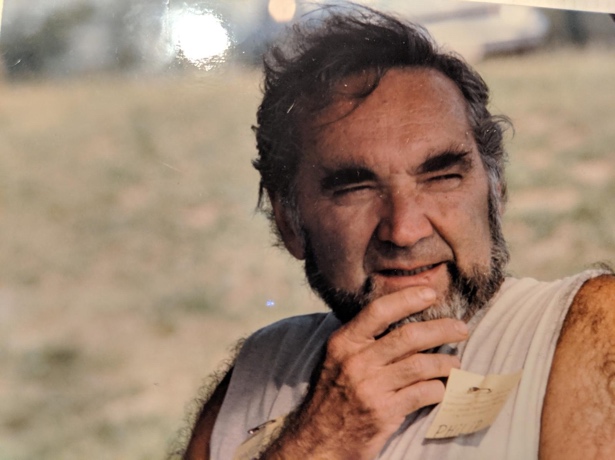

Philip Hallie was a fascinating man, if you haven’t gotten that already. His worldview was informed as much by his studies of philosophy and ethics as his own life experiences — mainly his youth, growing up poor and Jewish on the tough streets of 1930s Chicago, as well as his time as a soldier, during WWII.

Just as interesting, though, is that his worldview — particularly in his later years — seemed to be constantly shifting, sometimes dramatically so. As a result, I have to admit, it’s been hard to fully grasp where he landed after writing about Le Chambon and then, suddenly, resenting it. But, since he died in 1994, I couldn’t just ask him. Thankfully, though, I did manage to find his daughter — who helped give me important context.

Michelena Hallie: He was just a very hyperbolic person in some ways. That’s just how he was – he lived life very emotionally.

This is Michelena Hallie, who was a teenager when her father’s book came out.

Michelena Hallie: I’ve thought a lot about this because my dad’s been dead for almost 25 years. He definitely had PTSD.

While it wasn’t surprising to hear her say this, given the things her father did and saw during the war, it helped to hear it from a family member.

Michelena Hallie: He and I were really close, but there was only one time that he talked to me about what happened to him in the war.

The only other time Michelena heard him talk about it was in the 1988 documentary “Facing Evil,” which you’ve heard a number of clips from already. In one scene, he talks quite candidly about the flashbacks he would experience due to the near constant ringing in his hears from having been so close to heavy artillery.

Philip Hallie: I’ll listen to the ringing in my ear, and then I see those heads — especially those heads, those beautiful young people.

Hearing her father’s words today, she feels particularly sad to know how much he struggled with his experiences during the war.

Michelena Hallie: I just think how much more he could be helped now if they had had that diagnosis.

That said, Philip Hallie was never fully overcome by his PTSD.

Michelena Hallie: My father could put any of that aside to be a great dad.

And he was able to analyze himself. He may not have had our current advancements in therapy, but he had an idea of what was going on in his head. He knew that the source of his resentment toward Le Chambon — stirred by that letter — was the fact that he was in an existential bind.

Philip Hallie: Because I want my cake and eat it too. I want to believe in the preciousness of life and be a killer too. And because I feel this way, I have to pay a price, morally. I have an obligation to pay a price, and the price is agony, and I pay it.

Hallie also knew that he wasn’t alone in feeling that way.

Philip Hallie: Now, that labyrinth, that jungle of thought and feeling is my condition, and it’s the condition not only of Vietnam veterans who came from an unpopular war, but from all veterans who just have a modicum of decency.

So, it was at this point that Hallie decided it might actually be more beneficial for him to study someone more like himself than the people of Le Chambon. He felt that they were too good for him to understand. He needed to learn from someone with his background, someone who fit his description of a “decent killer.”

But it may surprise you who he turned to for this. Remember Julius Schmähling, the German major who may have helped protect Le Chambon from Nazi reprisals? Hallie had always found himself intrigued by the major, but — in the course of writing his book — he never got Schmähling’s full story. All he knew was what the people of Le Chambon had told him or what he had read in André Trocmé’s memoirs. So, he set out to find more information and hoped that — in learning to appreciate someone as morally dubious as Schmähling — he might learn to appreciate himself a bit better too.

Unfortunately for Hallie, the major had passed away almost a decade earlier, in 1973. But his middle-aged children were willing to be interviewed. So Hallie visited them in Germany and even got to read through Schmähling’s journals. The whole time he was expecting to find some simple explanation for why the major showed mercy to so many people. Perhaps he was religious, as André had thought. Or perhaps, since he taught history and literature, he had developed some humanistic theory about the world.

But as it turned out, Schmähling was non-religious and non-ideological. According to Hallie, he was simply a person who “made room for thoughts and acts of love.” Nothing big. You definitely couldn’t call him a hero. It’s not like he saved everyone in the Haute-Loire region. Nor did he ever try to undermine Nazi objectives — or publicly disavow himself of their evil deeds. He simply wasn’t as bad as most others in his position. And his non-actions prevented the loss of perhaps thousands of lives.

Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that this interpretation has been controversial. Affording a Nazi officer any benefit of the doubt is bound to do that. And there are certainly other factors that protected the plateau that had nothing to do with Schmähling — namely its remoteness, which dis-incentivized the Nazis from stationing many troops there.

In the end, though, it seems Hallie’s study of Schmähling — which he wrote about in essays over the final years of his life — helped him accept the idea of imperfect goodness. In his words, he said, “I have learned that ethics is not simply a matter of good and evil… It is a matter of mixtures… We are not all called upon to be perfect, but we can make a little, real difference in a mainly cold and indifferent world.”

Not long after wrapping up his research into Maj. Schmähling, Hallie was struck — almost literally — by another way to look at the goodness exhibited in Le Chambon.

Philip Hallie: We had a hurricane in Middletown, Connecticut, a couple of years ago. We watched it uproot our favorite chestnut tree, and then all of a sudden there was a blue sky and around this blue was a vast raging hurricane.

The fact that such a bright, hopeful blue could persist in the middle of a harrowing storm really spoke to Hallie.

Philip Hallie: I feel now that we can push back and expand the blue. We have to make room for love, even the most vicious and destructive of us, perhaps especially the most vicious and destructive of us.

This seemed to give Hallie some peace of mind. It was a way to square his conflicting feelings. And in his final words on the subject — for the 1994 reissue of his landmark book — he said the story of Le Chambon gave him a feeling of “unsullied joy,” something “necessary and useful killing” did not. And that’s because the people of Le Chambon fulfilled what he considered to be one of the only basic universal facts: “the belief that it is better to help than hurt.”

Knowing this, it’s impossible not to conclude that finding the story of Le Chambon had made Philip Hallie’s life demonstrably better.

Michelena Hallie: He was really facing despair before he found the story of Le Chambon. It really pulled him out of that.

That’s Hallie’s daughter, Michelena, once again.

Michelena Hallie: He loved going to do the lectures and talking to people who were involved or had similar stories — and just to focus on the goodness, as opposed to being mired in the evil and misery that he had put himself through for all those years.

This idea of “imperfect goodness” probably would have resonated with the Trocmés as well. As much as Hallie painted them and Le Chambon — in his own mind — as the ideal of ethical perfection, they certainly never saw things that way. Remember what Magda said in an earlier episode?

Magda Trocmé: When we speak of nonviolent resistance in Le Chambon, it doesn’t mean that all the people in Le Chambon were nonviolent. It means that they understood the situation of that period. They understood that the Jews were to be saved. It doesn’t mean that it was a conversion to nonviolence or that it was going to last forever.

In other words, the Trocmés weren’t trying to operate in idealistic conditions — just reality, which was a mixed bag. And they didn’t see themselves as above reproach, as you’ll recall.

André Trocmé: I do not believe I am better than other men. Like everyone else, I have to take some responsibility for wars.

As much as they opposed war, they knew they couldn’t bury their heads in the sand over it. And by the time Hitler invaded Poland, they weren’t going to waste time arguing that it shouldn’t be fought. They knew it wasn’t that simple — that the time to stop the war had already passed and that, frankly, ending war meant addressing a slew of underlying injustices.

Magda Trocmé: Outlawing war would mean eliminating the causes of war: patriotic arrogance, the individual or collective profit that drives our actions, competition for vital resources, the oppression and exploitation of one nation by another, racism and the cult of military glory.

So, when Hallie became obsessed with the idea that Le Chambon, or even “a thousand Le Chambons” as he said, wouldn’t have stopped Hitler, he may have been right, but he also was missing the point. They weren’t trying to stop Hitler’s militaries. They were trying to defeat his agenda.

Pierre Sauvage: In reality, rescuers were the only people who defeated the Nazis. Yes, the military obviously defeated the Nazis too. The Third Reich was destroyed. But one of the primary goals of the Third Reich was the murder of people, and the only people who really effectively resisted those murders were the rescuers.

That’s Pierre Sauvage, director of the film “Weapons of the Spirit.”

Pierre Sauvage: I think there’s no minimizing the fact that the people who acted were people who felt that there was simply no choice but to act. It was absolutely obvious to them.

And what they accomplished really needs to be better understood. So, let’s examine some numbers. There were roughly 350,000 Jews in France just prior to the German invasion in 1940. While 77,000 were eventually murdered in the camps — an absolutely horrifying number — somewhere around 75 percent of that pre-war population survived. That’s one of the highest survival rate of Jews in any occupied country.

There were a number of factors that made this possible. One is that official documents — like identification papers — were issued locally, rather than by the central government. This made forgery very easy. In fact, there were around 140 forgery teams around the country. Another reason for the high survival rate was that France bordered two countries that weren’t persecuting Jews: Switzerland and Spain. That made escape a viable solution for many — as we heard in this series.

A much larger number — maybe even the majority of Jews in France during the war — survived without escaping and without false papers. It helped that Jews had more places to hide. For the first two years, there was the unoccupied zone. But there were also areas of France that were controlled by Italy, which wasn’t interested in deporting Jews.

Nevertheless, those who survived the war in France could not have done so without some help. Perhaps it was a meal, some short-term shelter, a tip-off on a raid or a blind eye.

Such help wasn’t just limited to Jews in France either.

Patrick Henry: Historians tell us, and this is probably a very generous estimate, that one out of 200 people did anything to help a Jew during the Holocaust. Anything at all, even giving a crust of bread.

This is author and Holocaust scholar Patrick Henry.

Patrick Henry: Don’t ask me how people established such figures, but it means most people turned the other way.

In fact, it’s likely that the people who offered help, as we saw on the plateau, were repeat offenders. Some were just particularly inclined to help, while the vast majority of Europe was not.

Patrick Henry: I don’t condemn anybody for anything they didn’t do. I want to celebrate people who did do what now looks like unquestionably the right thing to do.

The people who helped the most and did so at the greatest risk — these are the people we consider the rescuers. And there’s actually an estimate for the number of Jews across Europe that they saved.

Patrick Henry: We’re talking about between 150,000 and 300,000 people.

That number represents about 5-10 percent of the 3 million Jews in Europe that survived the war. Six million, of course, did not.

And this is a good point to note that the rescuers weren’t exclusively Christian — because that is often the implication. The truth is: Jews played a role in their own survival as well.

Patrick Henry: There were many Jews who risked their lives to save other Jews during the Holocaust, and they need to be recognized.

What Patrick means by this is that they haven’t received the same awards that non-Jewish rescuers have received — awards like the one Yad Vashem gave to the Trocmés and the people of the plateau. That’s typically because non-Jewish rescuers are seen as having sacrificed their safety — whereas Jewish rescuers were already in danger simply because they were Jewish.

Patrick Henry: There are some people that don’t feel it’s not the same thing. I think risking your life to save another person, that’s what unites these two groups over any kind of religious differences.

What’s more, Patrick thinks giving the same awards to Jewish rescuers as non-Jewish rescuers would be a way of fighting anti-Semitism today.

Patrick Henry: It would also serve to further discredit the myth that Jews were led to their daughter like sheep. That myth is blaming the victim, and it’s very comforting to people who didn’t do anything to help the Jews during the Holocaust.

This is why Pat has worked hard to promote Madeleine Dreyfus’s story.

Patrick Henry: Madeline’s story is just the perfect exemplification of Jewish resistance. And Jewish resistance took many forms. But it was nonviolent resistance that saved the lives of Jews. Basically, it was not violent resistance. You couldn’t defeat this machine violently.

Even the Jewish partisans — fighters like the Bielski brothers, who were depicted in the 2008 film “Defiance” — knew violence was a losing cause, and they more-or-less tried to avoid it.

Patrick Henry: Tuvia Bielski said, “There are so few Jews still alive that it’s more important to save the life of a Jew than to kill a Nazi.” So that kind of makes you see them, again, in a nonviolent way, trying to avoid conflict to save the lives of the Jews they had together in the forest.

Pierre Sauvage was also quick to note the crucial role of nonviolence during the Holocaust.

Pierre Sauvage: I came to realize it’s a particular irony that Jews don’t attach special significance to nonviolence because it was really people who were engaging in nonviolence who were the people who helped us in our hour of need.

Now, Pierre wasn’t discounting the importance of defeating Hitler militarily.

Pierre Sauvage: God knows that was necessary too.

He just had another point in mind — one that few would ever consider.

Pierre Sauvage: The people who were engaging in violence were ignoring the plight of people who were being persecuted and murdered.

That is to say, they were fighting for other reasons: fighting to prevent or overturn German occupation. On the whole, the Allies weren’t fighting to save the Jews.

Pierre Sauvage: The people who weren’t ignoring the plight of people who were being persecuted and murdered were those who did not believe in violence.

The fact that this notion isn’t commonly understood — and probably likely to be rejected by many — says a lot about the way we are taught history and even our values.

Pierre Sauvage: Their story runs so counter to so many of the views that we have about life, about religion, about what is effective in such a situation, that we’re reluctant to let in that challenge, but we really must.

Pierre has one interesting theory as to why rescue is so often discounted in our histories of World War II.

Pierre Sauvage: It really was to a significant extent a female activity. And I think that history is mostly, mostly — not exclusively, and less and less, but certainly was traditionally — written by men, who get more excited about the clash of weapons on a battlefield, even when the battle produces no important result, than they are about the weapons of the spirit.

The reason women played such a key role should be fairly obvious.

Pierre Sauvage: It was often the woman who was at home when somebody knocked at the door. We certainly had in Magda Trocmé an example of how dynamic these women could be.

This speaks to the very nature of what makes nonviolent resistance so potent — it is available to everyone and therefore allows for the greatest level of participation. And numbers matter when you are trying to defeat an evil like the Nazis. As political scientist Erica Chenoweth has noted to some acclaim recently: It may take only 3.5 percent of a population actively involved in nonviolent resistance to topple an authoritarian regime.

That’s still, sadly, a far cry from Patrick’s statistic that one in 200 did anything to help a Jewish person. But it gives you an idea of what it might have taken for the Occupied countries of Europe to have completely stymied the Nazis and perhaps saved millions of lives. That sort of thing did actually happen in some countries, notably Norway and Denmark. But there are too many other factors at play — like varying levels of anti-Semitism, support for the Nazis and just general societal organization — to go too far down this rabbit hole of what-ifs.

It’s more important to look at what actually happened and to learn from that. So, what else can we say about rescue work? Well, here’s something that should speak more to the self-interest that we all possess.

Pierre Sauvage: There used to be a really old cliche that the good die young, and the reality is — I’ve come to realize — that the good die old. They aren’t as stressed as other people, and they die usually frequently in their beds surrounded by their loved ones.

And it’s not hard to imagine why.

Pierre Sauvage: People derive so much strength and satisfaction and gratification and happiness from facing problems and responding appropriately to them.

This was something Catherine Cambessédès told me when she was reflecting on her teenage years in Le Chambon during the war. If you’ll recall, her family sheltered Jews at one point.

Catherine Cambessédès: When we thought there was nothing we could do because we were occupied, because the Germans were heartless and did terrible things, when you thought “Oh dear, there’s nothing we can do” — when you’re active like this there is something you can do. And that felt very good, to do something, no matter how small, in the right direction.

So, what the people of Le Chambon and its surrounding villages were doing was on the one hand very simple: they were acting out of necessity, necessity for the people in danger, but also for their own sanity. On the other hand, what they were doing was deeply revolutionary because it posed a threat to any power that sought to divide and conquer.

Patrick Henry: The rescuers were talking about similarity between human beings at a time where Hitler was thinking about radical differences. The belief in a common humanity will stop us from a future genocide.

Pierre Sauvage: The key is never to turn away. The key is to realize that the other is you in another form.

There are, of course, people and communities embodying this belief today. Scott Warren of the Arizona-based humanitarian group No More Deaths is one example. A federal jury recently acquitted him on charges of harboring undocumented immigrants for having provided food, water and shelter to two Central American men traveling through the desert. Warren has argued that this sort of help is common practice where he’s from and that it’s not going to stop — no matter how much the authorities try to discourage people from doing it. This is him speaking on Democracy Now! earlier this year.

Scott Warren: Every day in the border region migrants, refugees, people who are coming across the border, who are coming through the desert, who are suffering, who are at risk of dying, are knocking on people’s doors, and they’re in need of water, and they’re in need of food. They’re in need of basic medical care and basic necessities. And people all across the border region are continuing to respond by offering these folks a glass of water, by offering them some rest or some food. And, frankly, I don’t see that changing.

Embed from Getty Images

Elsewhere in the United States, there’s been an upsurge in sanctuary cities — or places that have pledged to resist immigration enforcement. While the level to which they are willing to resist varies, and the movement itself is still somewhat undefined, it has become one of the more visible stands taken against the Trump administration. Less talked about are the 1,100-plus houses of worship, across at least 25 states, offering sanctuary to undocumented immigrants — a trend that certainly echoes with the story of Le Chambon.

Meanwhile, in Europe, there are people like Carola Rackete, the captain of a rescue ship run by the German charity Sea-Watch — which has saved the lives of more than 37,000 migrants. In June, Rakete was arrested in Italy after attempting to disembark 40 migrants who had been picked up at sea. Although some of the charges she faced have since been dropped, Rackete is still under investigation for human trafficking.

Carola Rackete: Well one of the questions which is asked very often is “Would I do it again?” Yes of course. There is a huge need for ships to be out there. People are dying everyday, so of course I would do it again. I mean it is our common border, our responsibility, more ships create a better possibility for people to arrive alive to the other side of that ocean.

Embed from Getty Images

Given that we are in the midst of another refugee crisis and rising authoritarianism around the world, you might be wondering what people who lived through the World War II era are thinking — people like the refugees who were sheltered in Le Chambon.

Renée Kann Silver: It is terrifying to me because that’s exactly the pattern I see. A pattern of growing fascism in this country.

That’s Renée Kann Silver.

Renée Kann Silver: I see tremendous analogies. It is such an overwhelming situation.

Hanne Liebmann doesn’t mince words either.

Hanne Liebmann: You know when I heard this person, Mr. Trump, [laughs] speak for the first time, I said, “Hitler!”

If that sounds extreme, just remember that she lived in Nazi Germany. So, she knows what she’s talking about. And when I spoke with her, she was particularly concerned about the Dreamers — the undocumented young people seeking a path to citizenship.

Hanne Liebmann: Now we have the story with these young people who were brought here by their parents. We want to throw out 800,000 young people. This is unheard of. It is beyond comprehension.

Peter Feigl feels much the same way.

Peter Feigl: Here’s a man, who’s telling the police “Rough em up. You’re being too kind to them.” The Nazis were very good at roughing up people, and they also had the blessing of the Führer to do that. I’m scared, and I’m reliving the past. I saw this before.

This is why all of these former refugees and survivors continue to speak to audiences about their experiences during the war. Hanne — who recently turned 95 — regularly visits her local college in Queens.

Hanne Liebmann: What I tell the students is they have to respect one another. They have to respect the other person as they want to be respected. Then I will ask them “What does hate do to you?” And they look at me, and I will say, “Well, you know what it does to you? It kills your soul.”

And what about the rescuers, what might they think? Well, again, it’s not surprising.

Nelly Hewett: They’d be destroyed. I think their ashes are turning over in their container. I don’t think they could imagine such bad tragedies.

This is Nelly talking about her parents, Magda and André Trocmé.

Nelly Hewett: They knew humanity’s frailties. But to go to the point where we are now takes a lot of negative imagination.

Similarly, Mark Whitaker expects his grandfather Edouard Theis would be utterly devastated by the world today.

Mark Whitaker: I think he really would have been upset by — even before the Trump era — about the kind of income inequality we have in America today.

More than just the policies themselves, though, Mark said his grandfather would be upset by the nature of the discourse.

Mark Whitaker: The total lack of kindness and compassion and just the way people deal with each other in political life. All of his heroic actions were rooted in very simple religious ideas. As a result, he didn’t think of himself as a crusader. I think he just thought of himself as somebody who was using his position to live what he preached.

It’s worth noting, however, that not everyone in Le Chambon was motivated by religion. Magda, despite being the wife of a minister, wasn’t driven by any kind of adherence to Christianity. Her spiritual views were more universal.

Magda Trocmé: Two ideas seem fundamental to me. We wouldn’t have, deeply rooted in us, a sense of ideals and hope, a need for justice, truth and love — no matter what our religion or degree of civilization — if there were not somewhere a well-spring of hope, justice, truth and love. And it is that well-spring that I call God.

So, at the end of the day, the beliefs that drove the rescuers were beliefs everyone can relate to.

Mark Whitaker: And so, if you want to talk about what do we do about the state we’re in right now, I think it shows that there are ways of participating that aren’t just waiting until the next presidential election. There are ways of participating that aren’t even directly political. I think there are other ways — in civic society, vis-a-vis your neighbors, people you come in contact with on a regular basis — that you can kind of spread the spirit of what they were doing in Le Chambon.

This idea of community is actually something Magda spoke about as being crucial to what happened on the plateau:

Magda Trocmé: It is important to know that we were a bunch of people together. This is not a handicap, but a help. If you have to fight it alone, it is more difficult. But we had the support of people we knew, of people who understood without knowing precisely all that they were doing or would be called to do. None of us thought that we were heroes. We were just people trying to do our best.

Despite knowing how devastated her parents would be to see the state of the world today, Nelly still has no doubt her parents would approach the problems we’re facing in the same way they always did.

Nelly Hewett: Oh yes, they would be involved all the way, absolutely. That’s what they did.

But since they’re not here, the next best thing she can do is share their story.

Nelly Hewett: I think we need to hear that there’s good in the world. And I’m very proud to be able to speak about what they did, to say that there is the possibility of goodness even in an evil world.

Any story of rescue or goodness, whether it’s the one that happened during WWII or anywhere else, is like a lesson that should be listened to and copied if possible. We have to have hope. If we don’t have hope then we’re finished.

Magda weighed in on this point as well toward the end of her life.

Magda Trocmé: We must not be afraid to be discussed in books or in articles and reviews, because it may help people in the future to try to do something, even if it is dangerous. Perhaps there is also a message for young people and for children, a message of hope, of love, of understanding, a message that could give them the courage to go against all that they believe is wrong, all that they believe is unjust. Maybe later on in their lives, young people will go through experiences of this kind — seeing people murdered, killed, or accused improperly, racial problems: the problem of the elimination of people, of destroying perhaps not their bodies but their energy, their existence. They will be able to think that there always have been some people in the world who tried — who will try — to give hope, to give love, to give help to those who are in need, whatever the need is. When people read this story, I want them to know that I tried to open my door. I tried to tell people, “Come in, come in.”

There is one more thing I want you to hear from Magda, and this time it’s her actual voice.

Magda Trocmé (recording): “Remember that in your life there will be lots of circumstances that will need a kind of courage, a kind of decision of your own, not about other people but about yourself.” I would not say more.

—

I began this series by saying “We all need stories that give us hope and help us see that it’s possible to overcome the evil that exists in our world.” And that’s the point I want to end on as well. But it’s important to also note that the hope is only real if it followed by action.

There are migrants and refugees that desperately need help today. Helping them can take many forms and may not necessarily look like what happened in Le Chambon. But by engaging in whatever way we can, by not turning away, we will still be following in their footsteps.

—

Thank you for listening to City of Refuge. I hope you’ve enjoyed this remarkable story of resistance and rescue. While this is the final episode of the 10-part series, there may actually be some bonus episodes coming soon. So keep an eye out. And if you haven’t already, please leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts. It really helps!

Another thing that helps is your financial support. Putting together this 10-part series over the last two and a half years has been a serious labor of love. As a reminder, Waging Nonviolence — the publication behind this podcast — is non-profit movement media platform, and we rely on a grassroots funding model to make this work possible. Visit wagingnonviolence.org/support to learn about our membership program — and the many gifts available when you sign up, starting at just $3/month. You can also make one-time donations. All contributions to Waging Nonviolence are tax-deductible.

Credits

City of Refuge was written, edited and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé were performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured the following songs:

- “The 49th Street Galleria” by Chris Zabriskie (license)

Special thanks to Robert Gardener for the clip of Magda Trocmé you heard at the end of the episode. It came from his 1985 documentary “Courage to Care.”

News clips came from the following sources:

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

“Tales of Good And Evil, Help and Harm” – a 1997 book by Philip Hallie

“We Only Know Men” – a 2007 book by Patrick Henry

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Courage to Care” – a 1986 book by Carol Rittner and Sondra Myers

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

Acknowledgements

I want to say thank you to everyone who helped and participated in the making of this series.

– First is my wife Jessica Leber, who not only appeared in part four, but supported me throughout the making of this series. She’s an incredibly talented journalist who edited all of my scripts and helped me whenever I was stuck — which was often.

– My colleague Eric Stoner, who first introduced me to the story of Le Chambon over a decade ago, and who read all my scripts ahead of time.

– Jasmine Faustino, who read early scripts and provided feedback on episodes before they were released. She also voiced Madeline Dreyfus in one episode.

– Brian McCarthy and Ava Eisenson, who brought brought the words of André and Magda Trocmé to life and really infused the series with their positive energy.

– David Tatasciore, who provided his audio expertise throughout and helped me learn Pro Tools.

– Will Travers, who wrote the wonderful original music for this series. He also listened to episodes ahead of release, gave me vital feedback and voiced Daniel Trocmé.

– Patrick Henry, who encouraged me from the beginning, answered many questions throughout and connected me with Nelly Hewett.

– Nelly, of course, was the backbone of this entire project, connecting me to just about everyone I interviewed. She also read and corrected my scripts. I can’t thank her enough for her hospitality, generosity and dedication.

Thanks also to everyone else who took time to speak with me:

– The survivors: Peter Feigl, Renée Kann Silver, Hanne & Max Liebmann

– Filmmaker Pierre Sauvage

– Edouard’s Theis’s daughter Jeanne Theis Whitaker and her son Mark Whitaker

– Catherine Cambessédès, who lived in Le Chambon during the war

– Philip Hallie’s daughter Michelena Hallie

– Cary Lane at Queensborough Community College

I need to thank all those who documented the story of Le Chambon before me and whose work aided me in my writing:

– Pierre Boismorand for his 2014 book “Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures,” translated by Jo-Anne Elder

– Christophe Chalamet for his 2013 book “Revivalism and Social Christianity”

– Deborah Durland DeSaix and Karen Gray Ruelle for their 2012 book “Hidden on the Mountain”

– Peter Grose for his extremely well-researched 2015 book “A Good Place to Hide”

– Philip Hallie for his 1979 book “Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” and the 1997 book “Tales of Good And Evil, Help and Harm”

– Patrick Henry for his 2007 book “We Only Know Men”

– Carol Rittner for the 1985 book “Courage to Care,” which accompanied the aforementioned documentary by Robert Gardener

– Pierre Sauvage for his landmark 1989 film “Weapons of the Spirit”

– Richard Unsworth for the 2012 book about the Trocmés called “Portrait of Pacifists”

– Mark Whitaker for his 2011 memoir “My Long Journey Home”

Finally, thanks to the institutions that housed some of the resources used in this series:

– The Swarthmore College Peace Collection, which is home to André and Magda Trocmé’s papers

– The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which conducted extensive interviews with survivors rescued by the plateau. They permitted use of these interviews, as well as many photos.

Hi Bryan,

Many thanks for this inspiring ten segment Audio-series.

Below, more on courageous collective nonviolent resistance.

Cheers, Björn Lindgren

SWEDEN

…

The Women’s Rosenstraße Protest in Nazi Berlin

by Nathan Stoltzfus

Albert Einstein Institution

Winter 1989/90

Many people believe that it was impossible for the Germans to resist the Nazi dictatorship and the deportations of German Jews. However, a street protest in early 1943 indicates that resistance was possible, and indeed, successful.

Until early 1943, Nazi officials exempted Jews married to Gentiles or “Aryans” (the Nazi term for German non-Jews) from the so-called Final Solution. In late February of that year, however, during a mass arrest of the last Jews in Berlin, the Gestapo also arrested Jews in intermarriages. This was the most brutal chapter of the expulsion of Jews in Berlin. Without warning, the SS stormed into Berlin’s factories and arrested any Jews still working there. Simultaneously, all throughout the Reich capital, the Gestapo arrested Jews from their homes. Anyone on the streets wearing the “Star of David” was also abruptly carted off with the other Jews to huge provisional Collecting Centers in central Berlin, in preparation for massive deportations to Auschwitz.

The Gestapo called this action simply the “Schlußaktion der Berliner Juden” (Closing Berlin Jew Action). Hitler was offended that so many Jews still lived in Berlin, and the NaziParty Director for Berlin, Joseph Goebbels, had promised to make Berlin “Judenfrei” (free of Jews) for the Führer’s 54th birthday in April. This “Schlußaktion” was, indeed, the beginning of the end for about 8,000 of the 10,000 Berlin Jews arrested in its course. Many who left their houses for what they thought would be a “normal” day of work, without turning back for even a last glance or hug, were to end up shortly in the ovens of Auschwitz, never again to see home or family.

About 2,000 of the arrested Jews who were related to Aryan Germans, however, experienced quite a different fate. They were locked up in a provisional collecting center at Rosenstraße 2-4, an administrative center of the Jewish Community in the heart of Berlin. The Aryan spouses of the interned Jews&emdash;who were mostly women&emdash;hurried alone or in pairs to the Rosenstraße, where they discovered a growing crowd of other women whose loved ones had also been kidnapped and imprisoned there. A protest broke out. The women who had gathered by the hundreds at the gate of the improvised detention center began to call out together in a chorus, “Give us our husbands back.” They held their protest day and night for a week, as the crowd grew larger day by day.

On different occasions the armed guards between the women and the building imprisoning their loved ones barked a command: “Clear the street or we’ll shoot!” This sent the women scrambling pell-mell into the alleys and courtyards in the area. But within minutes they began streaming out again, inexorably drawn to their loved ones. Again and again they were scattered, and again and again they advanced, massed together, and called for their husbands, who heard them and took hope.

The square, according to one witness, “was crammed with people, and the demanding, accusing cries of the women rose above the noise of the traffic like passionate avowals of a love strengthened by the bitterness of life.” One woman described her feeling as a protester on the street as one of incredible solidarity with those sharing her fate. Normally people were afraid to show dissent, fearing denunciation, but on the street they knew they were among friends, because they were risking death together. A Gestapo man who no doubt would have heartlessly done his part to deport the Jews imprisoned in the Rosenstraße was so impressed by the people on the streets that, holding up his hands in a victory clasp of solidarity with a Jew about to be released, he pronounced proudly: “You will be released, your relatives protested for you. That is German loyalty.”

“One day the situation in front of the collecting center came to a head,” a witness reported. “The SS trained machine guns on us: ‘If you don’t go now, we’ll shoot.’ But by now we couldn’t care less. We screamed ‘you murderers!’ and everything else. We bellowed. We thought that now, at last, we would be shot. Behind the machine guns a man shouted something&emdash;maybe he gave a command. I didn’t hear it, it was drowned out. But then they cleared out and the only sound was silence. That was the day it was so cold that the tears froze on my face.”

The headquarters of the Jewish section of the Gestapo was just around the corner, within earshot of the protesters. A few salvos from a machine gun could have wiped the women off the square. But instead the Jews were released. Joseph Goebbels, in his role as the Nazi Party Director for Berlin, decided that the simplest way to end the protest was to release the Jews. Goebbels chose not to forcibly tear Jews from Aryans who clearly risked their lives to stay with their Jewish family members, and rationalized that he would deport the Jews later anyway. But the Jews remained. They survived the war in Berlin, registered officially with the police, working in officially authorized jobs, and officially receiving food rations.

The implications of this protest are that mass, public and nonviolent acts of noncooperation by non-Jewish Germans on behalf of German Jews could have slowed or even stopped the Nazi genocide of German Jews. True, some six million Jews were murdered. Not many Jews were saved. Yet when the (non-Jewish) German populace protested nonviolently and en masse, the Nazis made concessions. When Germans protested for Jews, Jews were saved.

Although there were a few men in attendance, this was a protest by women; women were really the origin and the core of the protest. Women, traditionally, have felt responsible for home and family; to the women who were protesting, their families were, in some sense, their careers; to lose their families was to lose everything meaningful for them.

At the protest in the Rosenstraße there was a flickering of a tiny torch, which might have kindled the fire of general resistance if Germans had taken note of the women on the Rosenstraße and imitated their actions of mass civil disobedience. Perhaps they did not do so because they were used to thinking that neither women, nor nonviolent actions, could be politically powerful.

…

Nathan Stoltzfus received his Ph.D. in Modern European history from Harvard in 1993 and teaches twentieth century European history. His research and publications have focused on collaboration, resistance, and state control in twentieth-century Germany.

His book Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany (W.W. Norton 1996, paperback 2001 with a forward by Walter Laqueur) was published in German (Hanser Verlag/dtv).

—