Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part three of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part three of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

Last episode ended with Magda and André Trocmé headed back to Europe, ready to start their lives together and immerse themselves in the issues of the day. As we’ll hear in part three, they lived among struggling industrial workers and spoke out against rising militarism and fascism. These experiences — along with trips around Europe in the 1930s, including to Germany — helped them prepare for the strife that was heading their way in France. In the episode’s final moments, André takes his boldest step yet, one that sets the stage for the resistance and rescue operation.

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 3

Sometimes it feels like the world knows little more about nonviolence than it did a hundred years ago. I say this based mainly on the blank stares I receive when I tell people that I run a publication about nonviolence.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not surprised by the reaction. It’s not like nonviolence is taught in school. Most people’s knowledge of it begins and ends with a cursory connection to Gandhi and Martin Luther King. And if they even have an opinion of it, they tend to see it as a high-minded, but naive approach to resolving conflicts.

Few people know that nonviolent resistance is actually, statistically, the most effective method of resistance — responsible for bringing down dictators and winning most of the rights we enjoy today. Of course, the fact that I can tell you this is in fact evidence that we do actually know far more about nonviolence than we did a century ago. There’s even a whole field of academic study — known as civil resistance — that has been broadening our understanding of nonviolence for decades.

But in 1926, when Magda and André Trocmé returned to Europe, all they could really know about nonviolence was that it seemed to be working for Gandhi. They had wanted to meet him to learn more firsthand. But that didn’t pan out. So, with no real means to study nonviolence, they had to experiment and teach themselves. And that meant putting themselves in situations of personal and professional risk.

In this episode, I’ll explore the decade leading up to World War II — and bring us to the moment when France surrenders to Germany and two preachers in a tiny French village announce the start of a bold new experiment in nonviolence, telling their congregation: “The Duty of Christians is to resist the violence directed at our consciences with the weapons of the spirit…”

—

From 1927 to 1934, André and Magda Trocmé lived in Northern France, working in two very grim industrial cities. They were ugly depressing places, where smoke and soot permeated everything. Worse yet, though, were the people, who André and Magda described in their memoirs as living lives of real desperation.

André Trocmé: The population wasn’t interested in anything outside their life of forced labor and liquor.

Magda Trocmé: They were the by-products of human progress, desperate people, drinkers, really the dregs of society.

But that wasn’t the biggest problem they faced. Due to lack of Protestants in the region and a greater interest in the communist or socialist parties, André’s congregations were pretty small. Even his brand of Christian Socialism was no match for their contempt of religion. Not that André couldn’t sympathize. He was also at odds with the totally bourgeois Protestant Church, which was threatened by his politics, particularly his pacifism.

Since he didn’t have the thriving ministry he had envisioned, André needed to look elsewhere for fulfillment. Already, as a student of theology, André had become involved with an organization called the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, which was founded in 1914 and still exists today as one of the oldest organizations dedicated to nonviolence. And it was through this network that André became more immersed in peace work, taking bolder and bolder steps. This was 1932 and with war on the horizon, André threw his previous cautions to the wind to speak and write openly in support of conscientious objection. He also did something else that was unheard of — he accepted a visiting German World War I veteran, wanting to return to some of the French villages he had helped destroy and ask for their forgiveness.

André Trocmé: I was deeply moved by the prospect of a German finally feeling and expressing his remorse. He was, to my knowledge, the first German to return to the site of his ill-considered actions and ask his French victims for forgiveness. As such, he should have been welcomed, heard, understood and even celebrated.

But that isn’t quite what happened. Even 14 years after World War I had ended, anger and hatred toward Germans was strong. While André’s own small congregation received the veteran warmly, the other towns they visited were scandalized.

André Trocmé: I tried in vain to calm them down. A minority wanted to hear what the German had to say. He did manage to say quite a bit, but the atmosphere was so negatively charged that everything he said ended up being taken the wrong way. His emotional confession inspired only shouts of hatred and derision from the majority of the audience.

While André managed to end that particular meeting before it got any more out of control, he found that the authorities in the next town the German was set to visit had already canceled the event. What’s more, he was now a known troublemaker.

André Trocmé: My career as a clergyman had been seriously jeopardized by my actions, which were considered to be those of a “militant.” I was now under the surveillance of the secret police.

In some ways, this must have been freeing, as André no longer had a pristine reputation to protect. Feeling emboldened to act more in accordance with his beliefs, André joined a March for Peace in Europe in the summer of 1932. It had been organized by the international nonviolence group he had joined with the goal of spreading the urgency of reconciliation to avoid another great war.

André Trocmé: For a couple of weeks I took part in the march through Germany. We formed a solid team made up of Germans, English women, and me, the one Frenchman. Every night, in packed rooms, we addressed assemblies convened by an association with socialist leanings. In Frankfurt, we were incredibly successful, and the audience nearly carried us on their shoulders in triumph. In Heidelberg, the meeting nearly turned into a brawl. Two groups of young people, one Nazi and the other Communist, confronted each other.

This sort of clash happened nearly every day in Heidelberg. But then an odd thing happened, they united in their hatred of André and his fellow pacifists. It was the one thing the Nazis and Communists had in common.

André Trocmé: Each of them accused us of siding with the adversaries. At the end of the evening, we nearly fell victim to the Brownshirts.

These were Hitler’s paramilitary.

André Trocmé: I was taken aside by one of them, who was waving a revolver in my face, I suggested to him in German that he should kill me right there in front of everybody. My proposal seemed to have calmed him down because he disappeared into the crowd.

But that wasn’t even the craziest encounter on his trip. In southern Germany, they found themselves in a theater taken over by Brownshirts. They were trying to shut down the event, but André and his colleagues decided they couldn’t back down. So, they entered the venue through the back door. André went first because he spoke the best German.

André Trocmé: Before the four or five hundred Brownshirts had a chance to react, I shouted out Hitler’s own words in a booming voice: “Germany Awake!” For a few seconds, there was a stupefied silence. I took advantage of it to launch head first into the issue of the day: the need to awaken in the face of the coming danger of the Second World War.

André went on to explain his call for reconciliation and support for the equal treatment of Germans, thereby recognizing one of their key grievances since the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I.

André Trocmé: “Down with arms!” I said. “Today, the Christian who is responsible is opposed to war and the actions that prepare for war. He is a conscientious objector.” A thunder of applause answered me! The match had been won.

Except it hadn’t. André realized this when a Brownshirt came up to him afterwards and said…

André Trocmé: “You have precisely expressed what our Führer tells us every day: justice for all, equal treatment for all and peace for all.”

It turned out the German Brownshirts had only heard what they wanted to hear. André tried to argue back.

André Trocmé: “Yes,” I replied. “But I didn’t say it in the same way, and why does your Führer persecute the Jews if he believes that?” The young man responded by saying that it was because “the Jews are the number one enemy of peace.”

André could see that he had not and would not create any real change that day. At the same time, though, it was an important wake-up call — one that helped him see the dangers that lay ahead more clearly than much of the world at that time.

Meanwhile, back in France, Magda got her own wake up call. She had accepted a job at the local primary school to teach several classes in Italian. The school served the children of mostly Italian immigrants. So, Magda saw it as an opportunity to help these children keep up with their native language. The only problem was with the books, which had been supplied by the Italian consulate.

Magda Trocmé: As soon as I had a moment, I opened the books and what did I see? Magnificent pictures. Even the font and the paper were beautiful. But sprinkled generously throughout the book, like salt and pepper, was a seasoning that was 100 percent fascist! The books spoke of Mussolini as Italy’s savior. Basically, it was fascist brainwashing.

There was no way Magda would allow herself to teach this propaganda. So, she announced her resignation to the consulate, while also denouncing the Italian government. They were furious, but it felt like a personal triumph, particularly as the daughter of an Italian colonel.

Magda Trocmé: Once and for all, I got rid of fascism, which had been persecuting me up until that day.

Of course, she knew it wasn’t gone from her life entirely. Like André, she had simply become bolder about her beliefs at a time when she saw how important those beliefs were. Much of the world was not yet prepared for what would come. But Magda and André — because of their direct experience with fascism and Nazism — weren’t going to be taken by surprise.

Magda Trocmé: I had seen how Mussolini started. My husband saw what was happening in Germany. So we were prepared to understand what may happen in France before other people.

—

This is a good place to take a quick break and tell you about Waging Nonviolence, the publication that’s bringing you this podcast. Earlier, I talked about the wealth of information that exists for activists today — and how different that is from a century ago, when people like André and Magda were trying to take action against injustices. Much of what they did was invented on the fly and through trial and error.

Today, you can go to a website like Waging Nonviolence and learn how movements — both past and present — find success. In fact, one of the main reasons we started this publication was to serve as a sort of meeting place for activists and organizers from around the world, so that they could share information about what works and what doesn’t. And now, after 10 years, we have an archive with thousands of stories from more than 80 countries.

And some of these stories have proven to be quite influential. A few years ago, we published a series by Mark and Paul Engler, two rather brilliant movement thinkers who happen to be brothers. That series of stories became a book called “This Is An Uprising.” It offers a new understanding of how movements are able to build momentum and ultimately leverage power.Since its release “This Is An Uprising” has become a bit of a phenomenon — and it has spawned a new approach to organizing used by many of today’s most powerful and important movements.

If that sounds like a book worth reading, I have exciting news: You can get a copy when you become a sustaining member of Waging Nonviolence, starting at $3/month. Just head over to WagingNonviolence.org/support and you can sign-up there. You’ll also see that we have a number of other great gifts on offer, and you can choose multiple gifts starting at $5/month.

So, please do support our work. And know that when you do, you are helping to grow the wealth of knowledge that fuels today’s movements. Now, back to the story.

After seven years in Northern France, living in two very tough industrial towns, the Trocmés were ready to move on. They now had four young children to worry about.

Nelly Hewett: They wanted to move because the climate and the coal dust was so unhealthy that we were not very healthy children.

That’s Nelly Hewett, the oldest of the Trocmé children, and the only one still living, now in her nineties. Some of her earliest memories are of this time.

Nelly Hewett: I remember how black it was, and mother used to change us twice a day because we were playing in the garden in the black dirt, black dust.

She became so feverish from breathing that air that André and Magda were forced to send her away to a children’s home in Switzerland, where she could recover. This clearly could not go on. So André began looking for a new church that would take him on as its pastor. Now, you might be thinking this is why the Trocmés ended up in Le Chambon, a mountain village with plenty of clean fresh air. But it’s actually not — André actually wanted to be near an industrial city.

André Trocmé: I swore I would not be a pastor in the country. It has always been the city and its urban problems that drew me in.

And so he sent out applications to all his top choices. But, remember, André was now a known troublemaker, taking positions on war that were not accepted by the church hierarchy.

Nelly Hewett: The administration of the French church forbid the church where my father had applied. They’d said ” If you take Trocmé as a pacifist it will create a rift in the church.”

And so André was turned down by his top two choices, leading him to feel desperate and worried about his future.

André Trocmé: I will end up on the street or on the steps of the church. All that will be left for me to do is play dead.

Just as things seemed entirely hopeless, André received an invitation to become the minister of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. He knew nothing of this small village in the mountains of south-central France. The fact that it sat 3,000 feet up on an old volcanic plateau, hours from any major city was not appealing. Nor was its rather scant population of around 2,500 people. But the position was his for the taking. The village offered to hire him on an interim basis, which was a calculated move. The Protestant Church hierarchy couldn’t block interim appointments. So, André really wasn’t in any kind of position to say no.

André Trocmé: Le Chambon was a take-it-or-leave-it situation. I took it.

Nelly Hewett: And so he arrived in Le Chambon as a temporary in 1934. He had been an urban fellow, a university fellow, a multilingual fellow, my mother too, all their life. So they had no alternative. They had to adjust.

Why did this tiny village want André Trocmé, a pacifist troublemaker, a thorn in the side of the Protestant Church? Well, quiet and remote as they were, the people of Le Chambon and the wider plateau carried quite a proud history of progressivism and resistance. Unlike the rest of France, where Protestants numbered less than 1 percent, they comprised a large portion of the plateau — about 38 percent. In Le Chambon that number was even higher, with its population being around 95 percent Protestant. What’s more, most were descendants of the Huguenots, the first French people who adopted John Calvin’s new faith at the time of the Reformation. They were persecuted by the Catholic kings of France up to the French Revolution. During that time, the plateau became a refuge and center of resistance.

Magda Trocmé: Those old Huguenots had lots of difficulties with the police and the army of the kings who were persecuting them. They had a horrible time.

There were massacres and mass exoduses, but also stories of bravery and perseverance, which became part of the local lore.

Magda Trocmé: There horrible were stories, like the one of Marie Durand, who was locked in a tower for 30 years. She went in that tower as a young girl. She only had to sign a paper saying that she would submit to the Catholic religion, it would have been enough to get released, but she remained there, using the time to write the word “resist” on a stone.

Stories like these helped the people of the plateau identify with all who were persecuted and tended to incline them toward more staunchly left politics. But unlike the more secular left of the Industrial North, the plateau’s leftism was firmly rooted in Christianity — specifically the kind of social-justice, pacifist-oriented Christianity that André subscribed to.

Despite all that, however, André was still pretty down on Le Chambon when he, Magda and their children arrived in the summer of 1934.

André Trocmé: The town of Le Chambon is ugly. Dreary granite facades alternate with dilapidated hotels covered with dirty yellow or grey stucco. The whole thing looks unbearably sad.

Nelly had a similar first impression.

Nelly Hewett: I remember how drab the village was. Granite homes, on the sidewalk. No front lawns or anything. No color. Those Huguenots were poor, and they were austere too.

Still, André was a man of big ideas, and even though the setting was less than inspiring, he immediately got to work on breathing new life into Le Chambon.

Among the problems the village faced was its lack of a secondary school or high school. That meant the young people of Le Chambon had to leave the region for further schooling or work in the cities. In short, the village was suffering from wasted potential and a serious brain drain.

Building a secondary school was already an idea before the Trocmés arrived. But they were eager to support it. In fact, it was Magda who gave the idea its vision.

Nelly Hewett: When Dad said “Let’s start a school,” Mother said “Yes, we start a school with a different philosophy: boys and girls together, an honor system, we talk about war and peace. We talk about human questions, but we will prepare for the university so that the young people will stay on the plateau.”

André was very excited by the idea, and — by the time he proposed it to the village leaders — it was fully infused with his and Magda’s particular set of values.

André Trocmé: I had long dreamed of starting a secondary school that would be free of the narrow-minded nationalist teaching of history, where students from every country of the world would come to learn about peace.

The village was in full support of the idea given its history of progressivism. And, what’s more, it was already a sort of youth haven. Due to the fresh mountain air, city parents would send their children to Le Chambon for health and recreational purposes. That gave the village a real economic boost during the summer months. So, an international secondary school would not only fit right in, but it would give the village a chance to earn money during the winter months as well.

Over the next year, the Trocmés worked with the village leaders and individual protestant supporters to get everything set up. It was called the Ecole Nouvelle Cévenole — a name that referenced a nearby mountain range.

Nelly Hewett: Les Cévennes, a bunch of mountains south of Le Chambon, which were a refuge for Huguenots during the religious wars. So it was called Ecole Nouvelle Cévenole. Nouevelle because it was new in concept and Cévenole because it was Protestant.

Again, though, it was a kind of Protestantism that was both worldly and progressive.

André Trocmé: We wanted to be laymen in spirit, but Protestant and international in practice. A means of expression of the ancient Protestant left, still so much alive in the region, had to be invented, and I insisted on the promotion of pacifism.

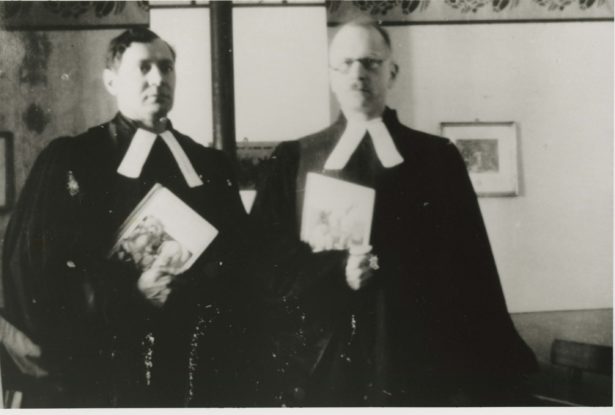

One of the most important tasks was finding someone to run the school. Someone recommended a man named Edouard Theis, and — as it turned out — he and André were already well acquainted. For starters, they had been in the same theology program back in Paris. Edouard was two years ahead, and like André, he had spent a year studying in New York, where he also tutored the Rockefeller children — it was something of a tradition for the Rockefellers to hire French theology students.

Despite this shared background, however, the thing that mattered most to André was that Edouard Theis was an avowed pacifist. This made him the right person to carry out the vision for an international school of peace. But Edouard was to be more than school director. He would also serve as André’s assistant pastor — a role that would make him integral to the incredible things to come in Le Chambon. And, in many ways, he was an unsung hero.

Nelly Hewett: They always speak of André Trocmé because he was charismatic, he was warm, he made contact.

That’s Nelly during my first phone conversation with her.

Nelly Hewett: But you know that they always forget his colleague Edouard Theis.

The “they” she’s referring to are most written accounts of what happened in Le Chambon. Edouard Theis just doesn’t get much play. That was something I hoped to rectify, but I also didn’t think the odds were very good on finding someone who knew him and spoke English. After all, Edouard died over 30 years ago in France. But then Nelly came to my rescue yet again.

Nelly Hewett: His daughter is in a rest home near Swarthmore, and she might be willing to have you talk to her.

Swarthmore, Pennsylvania is only a couple hours away from me. So, I made the trip to meet with another 90-year-old woman.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: Well, André Trocmé and his wife [laughs] are much more verbal than my parents.

That’s Jeanne Theis Whitaker, the oldest daughter of Edouard and Mildred Theis, who — like Nelly — seems to very much embody her parents’ most notable trait.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: My parents seemed to be rather silent.

Jeanne’s parents were both Protestant missionaries, when they met and married in Cameroon in the mid 1920s. In fact, that’s where she was born. But the family soon moved to Ohio, where Jeanne’s mother had grown up. Edouard took up teaching at a small college.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: He had the experience of teaching in America, which I think influenced him when he later founded the College Cévenol in France.

He liked the more relaxed atmosphere in American classrooms, where teachers and students could interact on a more equal level. In particular, he admired American schools for being coed — something that wasn’t done in France at the time. And he believed strongly in educating women — a passion that eventually became quite personal, as the Theises would go on to raise eight girls.

Eventually, the family moved back to Africa for another missionary posting in Madagascar. But Edouard’s heart was no longer in this line of work. He now had contempt for the colonial government and the Protestant Church’s role there.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: There was a little diary he kept in which he said that he felt he would be more fulfilled by teaching than by anything else.

This diary is actually quite interesting, because it’s one of the few personal writings about his life that exist. Although Jeanne couldn’t locate it for me, her son Mark Whitaker knew quite a bit more about it.

Mark Whitaker: There’s evidence in those journals, not only about his plan for this school, which became Cévenole, but also his concern about what was happening in Europe and his desire to sort of be closer to the resistance.

A few years ago, Mark wrote a memoir about his family called “My Long Journey Home.” While the book centers mostly on his experience growing up the son of a white woman and a black man in 1950s and ‘60s America, he also talks very lovingly of his grandfather, who he got to know quite well in his later years.

According to Mark, this journal is the closest Edouard ever got to a memoir, which is probably the main reason he gets so little mention in the histories of Le Chambon. Unlike the Trocmés, he left behind very little documentation.

Mark Whitaker: It just wasn’t in his nature to sort of think of himself as this person who history would be interested in and would therefore want to preserve every record of everything he had ever done. He was just modest in that way.

But he wasn’t modest in his ambitions. In the journal, under a headline “Projects for the Future” he speaks of his desire to create this progressive school and his yearning to join “the real battle” for “ nonviolence and a just social and international order.” So, as his daughter Jeanne put it…

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: He got his wish.

When the Cévenol school opened in October 1938, there were just 18 students. And because a school building did not exist, classes were initially held in the space behind the church. Soon, though, as Nelly told me, they spread out around the village, wherever available space could be found.

Nelly Hewett: People would say “Where is the New College Cévenol?” And we’d say “Everywhere!” Mother even taught a class in a large bathroom and laundry room at a friend’s house.

Magda was one of just four unpaid faculty members that first year, the others being Edouard, his wife Mildred and — remarkably — a Jewish refugee from Vienna named Hilde Hoefert. She was perhaps the first Jewish refugee to arrive in Le Chambon, having fled when Hitler annexed Austria in the Spring of 1938.

By the fall of 1939, as the school began its second year, many more refugees were about to begin their journey.

BBC News Report: These are today’s main events: Germany has invaded Poland and bombed many towns.

Then, two days later, on September 3…

BBC News Report: This is London: You will now hear a statement by the Prime Minister: “I am speaking to you from the cabinet room at 10 Downing Street… I have to tell you now… This country is at war with Germany.”

France also declared war on Germany that same day. While André had been anticipating this moment for years, now that it was here, he was struck by an existential crisis. He was a person who always took action. Building a school dedicated to peace as the world prepared for war was one thing. Now that war was here, what action could he take? The moment forced him to confront whether he was truly committed to nonviolence — and whether it was actually on the right path. Many thoughts raced through his mind, including — albeit briefly — the idea of assassinating Hitler. After all, he spoke German. Maybe he could find a way to infiltrate the upper ranks and just kind of end the madness before it got any worse.

Nelly Hewett: But then he gave it up right away because he said “That’s not what I should do as a pacifist. It is better to resist.” He was a factory of ideas. He was not a pacifist who would sit back, no.

In fact, it was really important for him to show — perhaps more to himself than anyone else — that his pacifism was not the result of cowardice or a refusal to carry his share of the burden. This was something he tried to make clear in a piece of writing from 1939. It was actually just a statement he wrote for himself, to better clarify his thoughts, which was found decades later.

André Trocmé: I am not a man full of pride rebelling against the world. I am not a zealot or a fanatic; I have never had a vision; I have a solid head on my shoulders. I am not exceptional in any way: I have a wife, four children and material needs. I have my faults, my miserable character flaws, just as everyone else does. I do not believe I am better than other men. Like everyone else, I have to take some responsibility for wars. I will not make any excuses for Hitler; in fact, he is the incarnation of the evil I detest. I have not discouraged any of the soldiers as they left for their posts, although my authority as minister would have allowed me to do so. I have no desire to return to the past, to my safe life. I only ask to be allowed to serve those in danger, the most pitiful victims of the war: women and children in the cities being bombed. I ask that my service be exclusively of a civilian nature. I am happy to give my life as others give theirs, without faltering in my faithful service to my master, Jesus Christ.

While André didn’t know what he was going to do, or where he would need to go to do it, he felt certain that he wouldn’t find the answer in Le Chambon — this quiet, safe, little village in the mountains. So, he offered up his resignation to the church council, comprised of the village leadership. What’s more, he didn’t want to drag them into whatever mess would ensue when he refused to go to war. But to his surprise, they would not accept his resignation. They supported his concerns and were willing to adapt to whatever might happen.

So, he continued on as minister through the winter. Then, in the Spring of 1940, the Germans began their march toward France.

CBS News: It is now 8:30 Tuesday morning in France. The latest dispatches from Paris describe thousands of French buses rolling out of the city, crowded with Army reinforcements, who have been streaming out of the French capital toward the front for 24 hours. Crowds lining the wide French boulevards cheer on the soldiers and thrust gifts of flowers and fruit through the windows of the buses, which are decorated with such slogans as “It won’t be long now” and “We’re on our way Mr. Hitler.”

André’s inner turmoil began to stir again. He sent a letter to the American Red Cross.

André Trocmé: I offered my services as a nurse or as a chauffeur, in order to help the civilian population in the war zone, and at a dangerous place, of course with no salary.

But the Red Cross turned him away. They could only take volunteers from neutral countries — or, at the very least, French men who had been exempt from the draft. André could claim no such advantage. Although he was now 40 years old, he could still be called to duty. And of course, he would refuse, which would set in motion any number of unpleasant outcomes. This prompted him to write a last will and testament.

André Trocmé: I know that my act of conscientious objection will not be understood. I know that I will become the object of the most terrible accusations: of colluding with the enemy, of spying, of being part of a fifth column, or who knows what else.

Worse than these things, however, was his fear of what might happen to Magda and their children.

André Trocmé: I know that I am setting the wheels in motion for the terrible hours my poor wife will suffer, and for my children to be subjected to trials that should not be faced by children their age.

There is clear dejection and even resignation in his voice.

André Trocmé: I could have left the country, become an expatriate. After all, I always knew ahead of time, with a clear and deep-rooted instinct, that my life would end in a violent manner. But I resisted the calls from other places and returned to my country. I am prepared to suffer anything.

But André never had to face the consequences of refusing to fight because the war between France and Germany ended before he could even be called into action.

CBS Rebroadcast of Nazi Announcement: The French resistance has collapsed and the Maginot Line has been broken, destroying all French resistance. Paris is an open city.

NBC News of the Word: Today French Envoys established contacts with German representatives to receive Hitler’s peace terms. In Bordeaux, the temporary French capital, Premier Pétain repeated that France was defeated and must give up the war.

Just six weeks after entering France, the Germans were marching down the Champs Élysées. On June 22, 1940, Marshal Philippe Pétain — an 84-year-old WWI hero — signed the armistice with Hitler. According to the terms of the agreement, the German Army would occupy a Northern Zone, comprising about three-fifths of the country, from the Atlantic coast to the Spanish border to Paris and the Northern industrial areas. Meanwhile, a supposedly “free” government led by Marshal Pétain — and based in the central town of Vichy — would run a Southern or Unoccupied Zone. This is where Le Chambon was located.

Given his WWI heroics, Pétain enjoyed fairly widespread popularity, which overshadowed the fact that he was in league with the Nazis, and would soon be enacting laws committed to furthering its war effort, as well as its racist anti-Semitic agenda.

Magda Trocmé: We could not be brainwashed as many people had been by the government of Marshal Pétain. Other people thought Pétain was a great hero, but this did not mean he was not a puppet for the new government. He was an old man. He was in the hands of a government that was basing their views on the Nazis.

There were some within the French government who strongly opposed the armistice, like Brigadier-General Charles de Gaulle, who fled to England before it was signed. In a famous speech broadcast in French by the BBC, de Gaulle called on the French people to “continue the fight as best they can.”

[Charles DeGaulle speaks in French]

De Gaulle’s speech has been credited as sowing the seeds of the French Resistance. But that resistance was still years away from taking shape. Meanwhile, on the plateau, André Trocmé and Edouard Theis were preparing a speech of their own — one that would foment a different kind of resistance and much more quickly.

On June 23, 1940 — the day after the Armistice was signed — they issued a joint statement, which André read instead of his Sunday sermon. He began by saying:

André Trocmé: Just as the Israelites of the Old Testament suffered, so we have come to our moment of suffering and humiliation.

He went on to talk about the importance of keeping hope alive, not blaming others for the country’s problems, and staying true to one’s beliefs.

André Trocmé: Have no illusions: the events of recent days mean that the totalitarian doctrine of violence now enjoys formidable prestige in the eyes of the world because it has, from the human point of view, been impressively successful.

André then spoke the words he is now most known for.

André Trocmé: The Duty of Christians is to resist the violence directed at our consciences with the weapons of the spirit. To love, to forgive, to show kindness to our enemies, that is our duty. But we must do our duty without conceding defeat, without servility, without cowardice. We will resist when our enemies demand that we act in ways that go against the teachings of the Gospel. We will resist without fear, without pride and without hatred.

Can you imagine hearing this speech in 1940, just days after your country was defeated by the Nazis and your government began collaborating with them? It was one thing for DeGaulle to deliver his message of resistance over the airwaves from London. But it was another thing entirely for André and Edouard to speak from within the belly of the beast.

Hoping that Nelly might have some memory of that day, I asked her to describe how the people of Le Chambon reacted.

Nelly Hewett: Well, it’s difficult to describe. Did I give you the name of Catherine Cambessédès? She was older than I was and so she understood better what was preached.

And, amazingly, she is someone Nelly still keeps in touch with.

Nelly Hewett: You might be able to interview her by telephone.

[Phone rings and Catherine answers]

And so, once again, Nelly’s network came through. And this time I was talking to someone who saw André Trocmé deliver his “weapons of the spirit” sermon.

Catherine Cambessédès: I don’t think there are many people who were there when I was there who are still alive. I mean I’m 93. It’s pretty old.

Well you don’t sound it. You sound great.

Catherine Cambessédès: [Laughs] Well my head’s ok, but it’s my body that’s just beginning to flinch.

Catherine then told me her memory of that day, as a 16-year-old girl. She went into church just utterly racked with fear and confusion. Her country had just lost a war, and was now divided and occupied.

Catherine Cambessédès: And I remember the feeling coming out of church thinking “Oh well, all right.” If everything that’s familiar to you is all of a sudden crumbling, what do you do? What do you tie yourself to? What do you hang on to? You don’t know what tomorrow will bring. You don’t know what anything will bring. And those two men said, well, actually the basic thing from which we live has not changed, and that was very, very soothing to hear that.

It wasn’t long before Catherine and her family — like almost everyone living in Le Chambon — became active members in a burgeoning spiritual resistance that would spread across the plateau. While the exact shape and form of this resistance was not yet clear to anyone — let alone André Trocmé and Edouard Theis — its parameters had been defined, and its soul awakened.

On the next episode:

Peter Feigl: 1938, during the annexation of Austria. I was nine years old, okay? I had been exposed to all the Nazi songs and so forth. I loved it as a young boy. I went to the town hall square and I stood there with 100,000 or more people yelling our heads off [says slogan in German] “One people, one empire, one leader.” When I came home, I very proudly said, “I saw our Führer.” And my mother slapped me and said, “That’s not our Führer.” And I was very confused. I didn’t understand.

Updates

The audio incorrectly states that Le Chambon’s population during the war was 900 and that almost the entire population of the plateau was Protestant. Le Chambon’s population was 2,500 and the platau was 38 percent Protestant. The above transcript contains these corrections.

Credits

City of Refuge was researched, written and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé are performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured music by Audionautix (license)

News clips came from the following sources:

- BBC News September 1, 1939

- BBC News September 3, 1939

- CBS News May 27, 1940

- CBS News rebroadcast June 14, 1940

- NBC News of the World June 20, 1940

- BBC News June 22, 1940

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jasmine Faustino, Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth