Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part four of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part four of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

In the last episode, I explored the years leading up to World War II, showing how the Trocmés and the people of their new home prepared to resist the violence and persecution about to sweep through France. In part four, we begin by taking a step back, in order to learn about some of the people soon to be sheltered in Le Chambon and its surrounding area — as well as the heroic efforts that led to their arrival.

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 4

When I began working on this podcast two years ago, I knew there would be some obvious parallels between current events and the WWII era. After all, the world is in the midst of the biggest refugee crisis since that time. But then, last year, about halfway through my work on this, the comparisons between now and then really hit home for me in a big way.

Democracy Now: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is in mourning after what’s being described as the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in U.S. history.

It was October 29, 2018 when a 46-year-old white supremacist walked into a Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh and killed 11 people. A couple of days later, information surfaced about his motives.

Democracy Now: Just before the shooting rampage, the gunman wrote on a far-right social media site, “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

HIAS — which stands for Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society — is the name of a Jewish humanitarian aid group that’s been around for over 100 years. Recently, they’ve been helping Muslim refugees resettle in America. The Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh supported those efforts, which is why it became the target of the shooter’s rage.

While it took this tragic event to introduce most people to HIAS, I was already quite familiar with their work. As it happens, they played a pretty important role in my wife’s family during the Holocaust.

Jessica Leber: They were the refugee organization that rescued my great Uncle Dick from France during WWII. So without them he would have likely died.

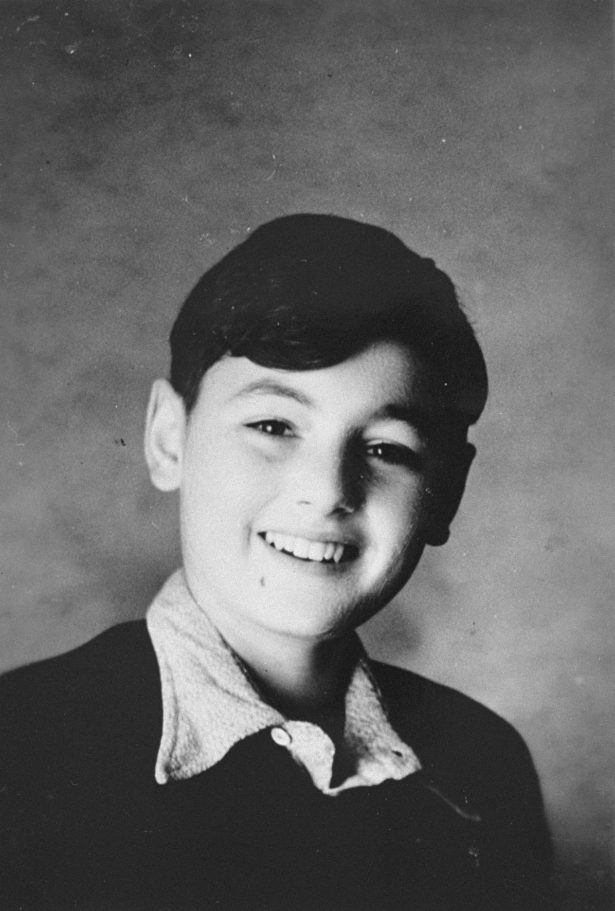

That’s my wife, Jessica Leber. Her great uncle Dick was only 10 years old when HIAS managed to get him released from a concentration camp in France and sent to the United States, where his much older siblings — including Jess’s grandfather — were living.

Jessica Leber: He was incredibly lucky.

Only 1,400 Jewish children were taken to the United States during the war. Interestingly, many of them, including Uncle Dick, came from the same internment camp. It was called Gurs. And it was actually in Southwest France, not Germany as you might expect. And because of that, there was a little more leniency, in that HIAS had been permitted to help out inside the camp. But HIAS wasn’t alone. There were actually dozens of aide groups helping out. Initially, they were just trying to provide some relief to the internees. Eventually, though, they realized aide wouldn’t be enough. They would have to find ways to get people released. And children were usually their best bet.

That turnabout, as we’ll discuss in this episode, is where the village of Le Chambon and its pastor André Trocmé come in. To put it simply, had things gone a little differently, Uncle Dick could have actually been one of the thousands of children helped by the rescue operation at the center of this story. And that realization has made working on this podcast all the more rewarding — both for me and my wife.

Jessica Leber: It’s crazy that you’re doing this podcast because I have such a strong connection to this story.

Do you feel like it gave you even more context for your family’s story?

Jessica Leber: It did, I only really knew my family’s story in isolation. I did not know it was part of this larger resistance and rescue effort in France, and it kind of helps make me feel even luckier than I do already that my family was a part of that.

So who were the Jewish people who came to Le Chambon? Well, to find out, I again turned to Nelly Hewett, daughter of Magda and André Trocmé.

Nelly Hewett: Very few survivors are still alive. And I can refer you to them. They may be reluctant to speak. We are all 90 years old. You are pretty much on the downslope.

That said, all of Nelly’s contacts thus far had been nothing short of age-defying. So I knew, despite her hedging, that I was sure to meet more incredible people with amazing stories to tell.

—

Peter Feigl is 89 years old and lives outside Washington, D.C. But he remembers his childhood in Austria like it was yesterday.

So, um… you actually saw Hitler speak to a crowd?

Peter Feigl: Yes

With your own eyes? You saw him?

Peter Feigl: I was in Vienna, 1938, during the annexation of Austria. I was nine years old, okay? I had been exposed to all the Nazi songs, music, martial music, the flags, the uniforms and so forth. I loved it as a young boy. I couldn’t wait to join.

This really blew my mind. Not only had Peter seen Hitler, but as a small boy — from a Jewish family no less — he was totally captivated by the Nazi propaganda.

Peter Feigl: When he came to Vienna, I ran away from home and went to the town hall square where he was supposed to appear, and I stood there with 100,000 or more people yelling our heads off [says slogan in German] “One people, one empire, one leader.” When I came home, my mother said, “Where in the hell have you been? You’ve been away for almost four hours.” And I very proudly said, “I saw our Führer.” And my mother slapped me and said, “That’s not our Führer.” And I was very confused. I didn’t understand.

To make matters more confusing, Peter’s parents had baptized him as a Catholic the year before. It was a precautionary measure. They weren’t religious Jews, and their primary concern was the safety of their son. So, young Peter saw himself as no different than any other Austrian boy.

Peter Feigl: “Why can’t I join the Hitler youth? I want a nice uniform and a dagger that goes with the uniform, and march with the other boys.” So, I just– the Nazi propaganda machine was very very powerful.

It was only weeks later that Peter and his family were forced to flee Austria, making their way into Belgium. But Peter wasn’t the only survivor I spoke with who had an unfortunately positive memory of seeing Hitler.

Renée Kann Silver: When I was four years old, on the maid’s day off, she decided to take me into town, and I don’t to this day understand that my parents didn’t realize what she had in mind.

This is Renée Kann Silver, now 87 years old, speaking to me at her home in Queens, where so many Holocaust survivors — like all four of my wife’s grandparents — settled after the war.

Renée Kann Silver: There was this parade with these tall big soldiers, and one of them took me on his shoulders, and I thought it was wonderful because there were all these red flags with these sort of funny crosses in the middle, fluttering around, and then this car came by and everyone was screaming, and then this guy standing in the car. And I thought it was wonderful.

Renée lived in the Saarland, now a state in western Germany. At the time, following the events of World War I, it was administered by France.

Renée Kann Silver: And of course when my parents learned where I had been — and, not only that, but that the maid had been doing the laundry for the Hitlerjugend, who were visiting with Hitler — she was not with us much longer.

It was only a matter of weeks before Renée and her family left for France. The Saarland had voted overwhelmingly to become part of Germany. Meanwhile, for Jews already living in Nazi Germany, life had been difficult for some time already.

Hanne Liebmann: We were children, but we realized — how old was I in ’33? I was nine. And there was the boycott against all Jewish businesses. I mean, even as a child you realize that something bad is going on.

This is Hanne Liebmann, now 94 years old. I spoke to her and her husband Max, who’s 97, at their home in Queens. Max was dealing with some health problems that day, so I didn’t get to talk for very long. But thankfully, the Liebmanns have both done extensive interviews with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. So, I’m going to turn to that archival tape now.

Max Liebmann: I was born in Mannheim, Germany. My parents were middle or upper-middle class and my childhood was very uneventful.

That’s Max, who coincidentally is from the same town as Uncle Dick and that whole side of my wife’s family — some of whom had already fled to the United States to escape Nazi oppression.

Max Liebmann: I have memories that there were the emergency police running around the city in their automobiles because there were always demonstrations and counter-demonstrations. We had a balcony where I could watch this very clearly. We were living on a fairly important thoroughfare.

Hanne, whose maiden name was Hirsch, grew up in nearby Karlsruhe and has similar early memories.

Hanne Liebmann: We lived and had our business next to a newspaper. This newspaper was a left-wing newspaper. And we had daily street fights, mob scenes, shooting, flag burning.

Then came Kristallnacht on November 9-10, 1938, when Nazi stormtroopers vandalized and destroyed Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues.

Hanne Liebmann: I went to school in the morning, Jewish school obviously, and something seemed wrong, yet I didn’t know what.

Max Liebmann: I went innocently to school not knowing about anything. And my mother called me around nine o’clock, 9:30. I should leave the school now, and I should go in the woods and stay there until the evening and call her again.

Hanne Liebmann: And when I came to school and I mentioned that I saw the fire engines standing in front of a building and in the back of this building was the Orthodox synagogue. I was told, “Don’t you know what’s going on?”

Max Liebmann: And on my way from the private school where I was to the railroad station — which was about a 10 minute walk — I finally understood what was going on in the city, because I saw [unintelligible] krauts clustered around houses where I knew there were Jews living and furniture flew out of the windows, et cetera, et cetera.

Hanne Liebmann: And when I came home all our show windows had been smashed. My mother was sweeping up the street. To the taunts and harassment of the population or the people who were made to look like the population.

—

By May 1940, with the war underway and Germany pushing into Western Europe, Peter and Renée found themselves in a precarious situation. Both were now in France and seen as foreign enemies.

Renée Kann Silver: They had picked up my entire family in May of 1940, the French did, and deported us as suspicious aliens, as spies.

Being Jewish actually had nothing to do with it. Their destination was Gurs, that internment camp in southwestern France I mentioned earlier. It had been built only a few years prior to house refugees from the Spanish civil war.

Renée Kann Silver: It was an awful place — just a gigantic, gigantic camp. They had a hospital for the horribly maimed Spaniards, some of them without legs, some of them without arms, and we saw a few of them without any limbs, just being carted in a wheelbarrow by their buddies.

Meanwhile, Peter and his mother had just barely made it into France — having fled Belgium during the invasion — when they too were taken to Gurs. Only, they were without Peter’s father, because he had been arrested as a spy — due to his German passport — while they were still in Belgium.

Peter Feigl: We were interned in Gurs for about six weeks.

Then the Germans entered France and freed everyone in Gurs. That may seem surprising, but Renée and Peter weren’t in the camp because they were Jewish — they were there because the French saw them as enemy aliens.

Renée Kann Silver: When the Germans came they literally said you can now go back to Lorraine. Lorraine is now German. They didn’t ask questions.

All that mattered in that moment was that they had won the war.

Renée Kann Silver: France had capitulated. France was in total chaos.

Free as Renée and her family may have been, they had no idea where to go next, having almost no money and only the clothes on their backs. Peter and his mother took refuge in a Catholic convent, eventually reuniting with his father, while Renée and her family settled in a suburb outside Lyon. But there was little respite before things got worse again.

Renée Kann Silver: Little by little we became aware of the fact that this was not really the France we thought we were staying in.

Shortly after France’s surrender, the Gestapo arrived at Hanne Liebmann’s apartment in Karlsruhe, where she was living with her mother, her aunts and her grandmother.

Hanne Liebmann: And so six women were eventually guarded by 12 Gestapo and policemen. Six helpless women. I was 16. My grandmother was 91 and a half. Totally not comprehending what was happening.

They told the women to pack and forced them to sign over the apartment and all their belongings. This was October 22, 1940, and the same thing was happening to Max and his mother, some 40 miles away in Mannheim.

Max Liebmann: We were brought to — I think it was — a railroad station, and then we were loaded into passenger trains.

It would have been natural to assume that they were headed to Poland, as the only other deportation of German Jews thus far had been east.

Hanne Liebmann: But it was very obvious once the train went, you know, was set in motion and we were going west, that we were not going to go to, let’s say, Dachau.

Their destination, as it turns out, was Gurs — the same camp where Peter and Renée had been imprisoned months earlier.

Hanne Liebmann: It was 6,500 people, I believe, that were deported to Gurs at the same time.

Nearly the entire Jewish population remaining in southwest Germany, including Uncle Dick and his parents. When my wife Jess interviewed him, shortly before he passed away in 2015, he relayed a very similar story.

Jessica Leber: Initially, my uncle Dick remembers them heading east towards Poland. And they didn’t know a lot about what was happening there, but they knew that would be really bad for them. So they were happy when the train actually turned around, unexpectedly.

The journey to Gurs took almost three days.

Hanne Liebmann: It was absolute horror. We had no food or barely any food was given to us.

Max Liebmann: There were a number of people who committed suicide.

Hanne Liebmann: Two of the old people, my grandmother being one of them, lost their minds.

The situation got so desperate that a doctor came up to Hanne with sleeping pills for her grandmother.

Hanne Liebmann: The intent of the doctor was to put her out. To really finish it right there and then.

As much as it pained her, Hanne thought the doctor was right.

Hanne Liebmann: I got them down into her. Unfortunately, she survived.

Max Liebmann: When we came to the camp entrance, it was raining cats and dogs.

Hanne Liebmann: It rained like you cannot believe. It was just like if you are standing under a huge shower.

Max Liebmann: It was night; and we were led somewhere and fed into barracks. Men and women were separated. Our luggage was dumped in front of the camp in the rain, and we were permitted the next morning to come and get it.

Hanne Liebmann: My experience, well, like everybody who got there — six and a half thousand people got there — was utter confusion. Most of the people were totally traumatized.

Around the end of 1940, André Trocmé — still feeling like he wasn’t doing enough — convened a meeting of the parish council. After two failed attempts to get away from Le Chambon in the past year, he thought he had finally come up with an idea that might stick and allow him to engage in some kind of humanitarian service.

André Trocmé: I put it to the council that they should send me on a mission into an internment camp as an ambassador to distribute food and other aid which would be collected by us from within the parish.

There were around a dozen internment camps in France at this point, holding about 50,000 internees. André knew that a good number of organizations — upwards of 40 actually — had been allowed into the camps to provide relief work, and he wanted to link up with one of them, maybe even live in a camp among the refugees for a while. With Edouard Theis, his assistant pastor, offering to stay behind and tend the ministerial duties, the council was quick to approve André’s plan.

André Trocmé: So I left for Marseille, where I made arrangements to meet with a delegation from the American Friends Service Committee.

This organization, often just called AFSC for short, was founded by Quakers a hundred years ago and is still around today, doing all kinds of vital peace and justice work around the world. André was no doubt attracted to them because of their impressive effort after World War I — when they managed to feed half a million starving Germans. But he also admired their clear commitment to pacifism.

During his meeting in Marseille, André was introduced to Burns Chalmers, a Quaker scholar and activist who left his post at Smith College in Massachusetts to do precisely what André was hoping to do: work in the camps. For the past six months, Chalmers had focused primarily on providing relief. But, like many of the aide workers, he saw they were fighting a losing battle. More camps were being built and more refugees were being added. If they were going to truly help these people, they were going to have to start rescuing them.

So, it was rather perfect timing when André came and met with Burns Chalmers.

André Trocmé: He told me not to go and live in the camps.

He explained to André how they were working with French doctors to get as many refugees as possible medically cleared for release. They would essentially invent ways to declare them unfit for work. The problem then became finding a French community willing to take in them in.

André Trocmé: “Could you be that community?” he asked me.

André immediately knew the answer.

André Trocmé: My unexpected duty was laid out clearly before me.

But he did, quite reasonably, ask how the village would afford to house and feed everyone.

André Trocmé: “Get the space and assistants,” Chalmers said. “The Quakers and the Fellowship of Reconciliation will give you the money you need.”

Whether or not Chalmers had the rank to guarantee such money is up for dispute. After all, André was the one who had connections with the Fellowship of Reconciliation. But the details don’t really matter here. The simple point was that they would find a way to make it all work, so long as the village was willing. And it was, of course, given its history and admiration of André.

André Trocmé: When I got back to Le Chambon, I won an easy victory with the parish council, who were happy to keep their pastor in town.

Many pastors kept in touch with each other, particularly the 12 Protestant pastors on the plateau, where Le Chambon is located. So they would have learned about the Quaker plan to house refugees in Le Chambon, each deciding for themselves how to get their villages involved. No doubt, they followed their consciences. After all, they too were steeped in the Huguenot history on the plateau. And it made perfect sense to them theologically-speaking. In the Bible, God directs the Israelites to set up six cities of refuge to protect those in trouble.

Writing for a church publication around this time, André made a similar appeal to his fellow Christians.

André Trocmé: “Therefore love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” This exhortation to the Israelites, in Deuteronomy 10:19, strikes us as being timely and fitting today. It has special relevance to us as people descended, at least spiritually, from the Huguenots who were persecuted in the 17th and 18th centuries. Once more, atrocious persecution is taking place. Hundreds of thousands of Christians, Jews, dissidents and democratically-minded people are trying to escape the oppression and violence of totalitarianism.

—

Before we go on, just a quick work about Waging Nonviolence, the publication bringing you this podcast. One of the things we try to do in our coverage of movements around the world is show how it’s possible to succeed in some of the most difficult circumstances imaginable.

And no one does this better than Waging Nonviolence columnist George Lakey, who is able to draw from his decades of organizing and training experience — as well as his seemingly endless knowledge of movement history.

In countless stories, George has made the case that movements succeed when they go on the offensive — even when faced with existential threats. The civil rights movement of the 1960s is one example, as is the LGBTQ movement of the 1980s.

George’s basic argument is that movements don’t win when they are fighting from a defensive position, trying to hold onto previously achieved gains. They win by setting new goals and fighting vigorously for them.

This is something you can actually see in the story of Le Chambon. While it’s true they were defending Jews and other refugees — they were doing it by going on the offensive, by creating an inspiring vision of a truly free France in the heart of Occupied Europe. And that vision — as we’ll see later in the series — helped them succeed when other resistance efforts were being put down.

George’s analysis, however, hasn’t just been helpful to me. More importantly, his columns have been read by many of today’s leading organizers and activists. So much so, that George recently released a book called “How We Win.” Not only does it expand on a number of his Waging Nonviolence columns, but he also considers it a successor to his seminal 1960’s Manual for Direct Action, which was an important resource to many during the civil rights movement.

If you’d like to read this important book, you can get a copy of “How We Win” when you sign up to be a sustaining member of Waging Nonviolence at $5/month. Just head over to WagingNonviolence.org/support. You’ll also see that we have a number of other great gifts on offer starting at just $3/month.

So, please do support our work. And know that when you do, you are helping to spread the kind of knowledge that empowers movements to succeed. Now, let’s get back to the story.

The Mediterranean port city of Marseilles, where André had met with Burns Chalmers, was a hotbed of relief and rescue activity in 1940. In fact, at the very moment of André’s visit, an incredible operation run by the American journalist Varian Fry, was in the midst of helping thousands of refugees escape Nazi Germany.

Given this kind of activity, and his close approximation to it, it’s not surprising that André’s co-pastor, Edouard Theis, heard about another rescue operation that piqued his interest.

Mark Whitaker: There was a woman named Martha Sharp…

This is Edouard’s grandson Mark Whitaker.

Mark Whitaker: …and she and her husband were Unitarians in Massachusetts.

Similar to the Quakers, Unitarians were actively engaged in issues of peace and justice.

Mark Whitaker: The Unitarians basically drafted them in the late ‘30s to go to Europe and to start helping people who wanted to get out of Europe.

The Sharps were quite successful, first helping many political dissidents escape Prague. The work took a toll on Martha’s husband, however, and by late 1940, she was working on her own.

Mark Whitaker: She decided that what she was going to do was to organize a mission to get refugee children out of occupied France. But the rub was that she was looking for children who had some kind of American connection.

As it happened, Edouard’s wife Mildred was American and, well, this seemed like the perfect time to send their children to live with her relatives. After all, they were getting involved in a very dangerous rescue operation themselves.

Mark Whitaker: So it was this mission organized by Martha Sharp that brought my mother and her sisters to America.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: Our parents took us down to Marseilles, and that’s where we left them.

This is Jeanne Theis Whitaker, Mark’s mother and Edouard and Mildred Theis’s oldest daughter. They had seven by this point, but only six were old enough to make the voyage to America.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: Mrs. Sharp and the people working with her took us across Spain to Portugal. In Portugal, we had to wait a few weeks before we could get room on a ship, but finally we were on a ship, which brought us to New York. I was 14.

That made Jeanne the oldest of the 27 children Sharp brought to safety as part of that operation. And camera crews were waiting for them at the dock upon their arrival.

Newsreel: The American liner Excambian arrived with child refugees from Europe, youngsters scarcely able to believe they’re free from the terrors of war.

Back in Le Chambon, the Theises were full of emotion. Catherine Cambessédès, who was friends with Jeanne and still living in the village at the time, saw Edouard that day.

Catherine Cambessédès: He had a long face. He was– I mean six of his children had just left.

At the same time, Edouard’s grandson Mark thinks he must have also been quite relieved.

Mark Whitaker: I can’t imagine it wasn’t somewhat easier for my grandfather to sort of face a lot of dangers that he faced.

—

One snowy evening, sometime during the winter of 1940-41, Magda Trocmé heard the doorbell ring. When she opened the door, she saw a woman standing there, in total disarray, wearing sandals that were completely soaked through by the cold wet snow.

Magda Trocmé: She told me she didn’t know where to go. She had left Germany and had made her way through France, zig-zagging east and west. She had been told there was a pastor in Le Chambon who would probably take her in.

This was the first Jewish refugee to show up on the Trocmés’ doorstep. A few French Jews were already staying in Le Chambon. Even some foreign ones who had managed to immigrate. But none had yet arrived on the run, without papers — “illegally” so to speak — simply because they had heard Le Chambon was in the practice of sheltering people.

Magda Trocmé: I invited her in to rest for a while, to eat something and dry out her shoes.

But, all the while, she was trying to figure out what she could do with this woman. So, she decided to speak to a town official, thinking he could help.

Magda Trocmé: But he got angry, told me it was ridiculous, there were already French Jews and I was bringing in German Jews, that the whole town would be in danger. He ordered me to send the lady away. Imagine: Send her away! Away, where? I was devastated.

Ultimately, André and Magda gave the woman some information on how to get to Switzerland through some connections they had with ministers and Catholic priests on the border. Unfortunately, they never found out if she survived the war. It was a tough lesson on the need to be better prepared.

Magda Trocmé: And so we decided that the next phase would be handled in a different way, this means hiding, and false papers and so on and so on.

In short, this was the beginning of the covert rescue operation in Le Chambon and the surrounding villages on the plateau. It sprung up at virtually the same time as André worked out a plan with the Quakers to take in refugees released from the internment camps. That plan, which had the blessing of the Vichy government — since it made them look good and lessened their burden — would soon provide a helpful cover for the plateau’s more clandestine activities.

—

Back in the Gurs internment camp, Max and Hanne were adapting as best they could.

Max Liebmann: It took a while to sort out where everybody was, but eventually we found out.

Hanne Liebmann: It was the young people who had to function first and did function first. And slowly, you know, things started to fall into a pattern.

Max Liebmann: The food was abominable. We had very little to eat.

My wife’s great Uncle Dick noted this as well.

Jessica Leber: He basically said to me, “You wouldn’t like it. It was no picnic there, but compared to where we were headed originally [toward Poland] it was like a country club.” He had a funny sense of humor like that.

And humor was no doubt needed, as death was also a fixture in the camp.

Hanne Liebmann: We would have in the beginning as many as 20 to 25 deaths a day! Because dysentery was just rampant, other diseases were rampant.

Hanne’s grandmother, for one, died within a couple of months.

Hanne Liebmann: I supposed that she must have gotten pneumonia or whatever from lying there. She just gave out.

Despite their losses, the imprisoned refugees still managed to create a life amidst their misery.

Hanne Liebmann: There was a tremendous cultural life in Gurs. There was chamber music, there was an orchestra. There were cabaret performances, lectures. Eventually a school for the young children was established, and the adults somehow formed some classes for English — still hoping that people will make it to an English-speaking country, namely America.

Max, who played cello, joined a quartet, and that came with some serious perks.

Max Liebmann: I had a permanent pass, and I could circulate in camp.

This helped him spend more time with his mother in the women’s barracks, where he also met Hanne, his future wife.

Max Liebmann: I met her in, I think, it was December of 1940.

At the time, Hanne was 16 and Max was 19.

Max Liebmann: We saw each other fairly frequently since I could circulate.

Hanne Liebmann: I don’t even think it was a courtship. It was a friendship, really. You know young people are sort of drawn together. Yes I fell in love with him, of course I did. But it was a totally platonic thing.

Then, in the summer of 1941, Hanne and her mother were approached by a social worker. She was from one of the groups helping out in the camps — a French Jewish humanitarian organization known as the OSE.

Hanne Liebmann: A social worker from the OSE came to see my mother and explained that there was a village, Le Chambon, who was looking to help young people — to take them out of the camp, and would she agree to let me go.

Hanne’s mother left the decision up to her daughter.

Hanne Liebmann: I said, “Of course.” And she never said, “But I will miss you. I don’t want you to go,” or anything like that. She let me go. She loved me enough to let me go. Because there were parents who did not. As incredible as it sounds, they held on.

Despite the horrors inflicted on the Jews up to this point, Auschwitz and the other death camps were not yet known to the outside world. So, it was understandable if there were families that thought it best to stick together. But, like Hanne and her mother, my wife’s family made the decision to part ways.

Jessica Leber: My great Uncle Dick told me, and I’m quoting this, “I remember saying goodbye to my parents. We were pessimistic that we would see each other again. We were hoping, but we were doubtful due to the drastic circumstances that we had no control over.”

Tragically he never did see his parents again. His father died in Gurs and his mother died in Auschwitz. They were my wife’s great-grandparents. But, thanks to HIAS, the Jewish aid organization, Dick was able to reunite with his siblings.

Jessica Leber: In late 1941, he got on a boat that took him to America. His sister picked him up, and he lived the rest of his life in New York City.

Meanwhile, Hanne was just beginning her journey to safety.

Hanne Liebmann: Together with six other young people, teenagers, we set off beginning of September 1941 to go to Le Chambon. And Le Chambon was, of course, heaven.

Hanne would be the first of the refugees in this story to make it to Le Chambon. In the waning months of 1941, Renée Kann and Peter Feigl were laying low with their families in other parts of France — trying to exist amidst ever worsening anti-Jewish laws. Meanwhile, Max remained stuck in Gurs, separated from his girlfriend.

Hanne Liebmann: We kept up a correspondence after I left. It’s as simple as that. I always knew where he was.

This connection would play an important role in Max’s rescue, as Le Chambon and the wider plateau became a true city of refuge.

—

On the next episode:

Catherine Cambessédès: I remember my brothers and me looking out the windowdown below us. There was a poster saying “Death sentence to anybody harboring Jews.” We had two of them right across the street.”

Credits

City of Refuge was researched, written and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé are performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Audio of Hanne and Max Liebmann was derived from the following interviews conducted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

- January 19, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- January 19, 1990 – Max Liebmann

- March 28, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- March 28, 1992 – Max Liebmann

- June 2, 1998 – Hanne and Max Liebmann

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured music by Audionautix (license)

News clips came from the following sources:

- Democracy Now! October 29, 2018

- British Pathé November 9, 1938

- News of the Day December 23, 1940

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jasmine Faustino, Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Hidden on the Mountain” – a 2007 book by Deborah Durland DeSaix and Karen Gray Ruelle

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth