Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part six of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part six of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

In the last episode, we heard how Le Chambon and the wider plateau were able to thwart the threat of arrests and round-ups. This episode, however, with the Germans in full control of France, the resistance and rescue operation faces its first crisis.

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 6

At the start of this series, I played one of the only recordings of André Trocmé that exists.

André Trocmé: The Jews were there around us. They came at our door, asked for protection.

In that recording, he went on to reference the danger and tragedy that accompanied their efforts.

André Trocmé: We simply hid these poor people in our homes, shared their fate — some of us have gone very far, also under persecution some of us have perished.

But so far, more than halfway through the story — and the war itself — we have yet to encounter any such tragedy. In fact, two years into the rescue operation, only one person had been arrested and taken away. Combine that with the couple hundred or so people who had been sheltered or helped into Switzerland, and it seems as though the plateau was nearly untouchable.

But that’s because the war — as bad as it was — hadn’t yet reached its absolute dire worst. Things took a turn in that direction, last episode, when the Germans — feeling threatened by the Allied invasion of North Africa — took over all of France in November 1942. This meant Le Chambon was no longer in unoccupied territory. Like the rest of southern France, it was going to be in the hands of the Nazis now.

As a result, more refugees than ever were on the move in France, and things were only getting more dangerous for those willing to help them. In this episode, we’ll begin to see that Le Chambon — despite its luck thus far — would not escape the war unscathed.

—

Even though the Germans were now occupying all of France, Vichy was still the greater immediate threat to the rescue operation. For one thing, they had direct knowledge of it. The people of Le Chambon had told a Vichy official to his face that they were hiding Jews and that they weren’t about to stop. For another thing, Vichy wanted to protect what little authority it had left — and the Germans weren’t going to look kindly on subordinates who tolerated open dissent.

That’s the likely reason Vichy ordered the arrest of André Trocmé and Edouard Theis on February 13, 1943.

Magda Trocmé: There was a knock on the door, and I found myself under the noses of two fairly high-ranking police officers who wanted to speak to my husband.

André wasn’t home. In fact, he was out discussing the rescue operation with the village youth. So, Magda invited them in to wait for his return.

Magda Trocmé: When he came inside, he found himself face-to-face with them. A few minutes later, he came out and said:

André Trocmé: That’s it, I’m under arrest!

Expecting that a situation like this might happen — and having heard first-hand what internment camps were like — Magda had, months earlier, packed a suitcase with the warm clothing André would need. But enough time had passed since then that the clothes got pulled out as needed. In a panic, she started to get Andé’s belongings together.

Magda Trocmé: “We’re not in a hurry” the police officers told me. “You can do what you need to do.”

So, Magda took them up on this opportunity to prolong what remaining time she had with her husband. She packed the suitcase and then told the police officers that it was supper time.

Magda Trocmé: “You can eat with us,” I said. They were extremely surprised. I didn’t do it out of generosity you understand. It was time for our meal, that’s all. They were embarrassed; one of them had tears in his eyes.

Magda then asked if she could call some of the other town leaders and let them know what was happening.

Magda Trocmé: “Oh, no!” they said. “No one can know that André Trocmé is being arrested!”

It turns out, they had taken some precautions to avoid this — namely cutting the Trocmé’s telephone connection. But a close family friend happened to stop by, saw what was going on and ran to alert the villagers. Soon enough, people were lining up to enter André and Magda’s home with gifts.

Magda Trocmé: They came in, wished André luck, gave their offering and then left. It was really quite moving.

Someone even gave André a roll of toilet paper, which was extremely precious in those days.

Magda Trocmé: It was only much later that my husband discovered it contained Bible verses, devotionals of encouragement. They were written hurriedly, every which-way, so that the pastor could have messages from his parish even in his camp or prison.

Another person gave André a candle, but without the matches to light it.

Magda Trocmé: And the police officer, the one who had tears in his eyes, took a box of matchsticks out of his pocket and put them on the table.

Meanwhile, outside the house, students from the Cévenole school also lined the street.

Magda Trocmé: When my husband came out, he walked between the two lines of supporters, who began to sing.

André said goodbye to Magda and his children, uncertain when — or if — he’d see them again. Then he got in the police car, and they drove to pick up his friend and colleague Edouard Theis. The two spiritual leaders of what was — at the time — the largest and most successful resistance movement in France were now under arrest. And what that meant was unclear. Maybe the movement could go on without these leaders. After all, as I mentioned last episode, everyone on the plateau was a leader in their own way. However, it’s possible that the departure — and who knows, even death — of two beloved preachers, might be enough to completely demoralize the plateau.

Nelly Hewett: We were worried because we didn’t know what was going to happen.

That’s André’s daughter Nelly, who remembers at least being relieved to learn that her father wasn’t going to a German concentration camp — but rather a French internment camp several hours away.

Nelly Hewett: It was full of communists, underground people who had blown railroads up, the rough cut of society. But it was not an extermination camp.

These communists weren’t exactly thrilled to have a couple of Protestant pastors espousing nonviolence in their midst. Not only did they disagree on religious and ideological levels, but they suspected André and Edouard might be double agents, or plants, placed among them to gather intelligence.

Magda Trocmé: Then they saw what my husband and his friend were really like, and that was when the men began to have experiences of real friendship and sharing.

André and Edouard managed to get permission from the camp’s commander to hold Protestant church services. With little else to do, a few of the communists attended. And as they heard the pastors talk about things that mattered to them — justice, equality and human dignity — word began to spread through the camp. The services quickly became a popular activity. Discussion groups formed and classes were organized.

It all sort of harkened back to the early days of André’s ministry, when he worked in the industrialized Northern cities of France. Those times had taught him how to connect with workers and communists — the basic rule being that you stress your common beliefs and show nonviolence to be another form of struggle, not passivity.

But the pastors from Le Chambon soon proved their mettle in another way.

Magda Trocmé: Suddenly, five weeks after they arrived, the order came for their release. Why? We didn’t know.

In fact, the reason for their release is still a bit unclear. But it was undoubtedly some combination of public outcry and pressure from people in high places — people like the regional prefect Robert Bach, who once threatened to deport André. For some unknown reason, Bach lied to Vichy, saying the people of the plateau had been won over to the policies of the government, and that the arrest of the pastors was having the effect of reversing that progress. It could be that Bach was just covering his own tracks for not being able to control the situation better. Or, perhaps André and the people of Le Chambon had earned his grudging respect. Either way, this lie no doubt contributed to the decision to release them. There was just one problem…

Magda Trocmé: At the last second, the director of the camp [told them to sign a paper that said: “I pledge to support the government of Marshal Pétain.”

He was the head of the Vichy government. So this went against everything they believed — not just politically, but religiously.

Mark Whitaker: According to the stories that I’ve heard, it was actually my grandfather who called this to Trocmé’s attention.

That’s Mark Whitaker, grandson of Edouard Theis.

Mark Whitaker: As soon as Trocmé focused on this condition, he said…

André Trocmé: It is a matter of conscience for us.

The director couldn’t believe what he was hearing, as André continued to explain.

André Trocmé: If we make that pledge and then break it, as we surely will, we make ourselves liars, and that is a violation of the ninth commandment. We are forbidden to bear false witness.

The camp director tried to convince them it was just a formality — it didn’t mean anything. But the pastors were insistent.

Magda Trocmé: They did not sign it and were immediately returned to the camp.

When their fellow prisoners heard the news, they mocked the pastors and their commitment to Christianity and nonviolence — arguing that you have to fight dirty against dirty opponents. André and Edouard weren’t in any mood to argue with them. They knew the decision not to sign that paper might have sealed their fate. What they didn’t know, however, was that people were still working to secure their release — and it seems likely the head of the Protestant Church, a man who had long opposed André’s radical beliefs, may have been one of the people who convinced the Vichy Prime Minister to make it happen.

Magda Trocmé: A few days later, a telegram signed by the prime minister arrived, saying, “The two pastors must leave immediately.”

The paper they were required to sign had been amended, basically exempting them from the pledge. The pastors quickly gathered their things, much to the shock of their fellow prisoners, who gathered together one last time to sing the traditional song of goodbyes.

It was an incredible turn of events. Had they stayed just two days longer, they would have been sent to a death camp in Eastern Europe — because that’s what happened to their fellow inmates, several hundred of them, none of whom were heard from again.

Was this just a lucky coincidence? Probably not. Surely someone in Vichy knew about the deportation in advance, and decided to have the pastors released before it happened. One explanation is that they were perhaps worried about the possible unrest that would spark on the plateau and Protestant France at large. Another explanation is that Vichy could also see that Germany was losing the war by this point. The Russians had just won at Stalingrad, wiping out a year of German gains. So, it was time for Vichy officials to start thinking about saving themselves. Letting some pastors go free might earn them a few points down the line should the allies win.

—

Before we continue, I have some quick news to share about Waging Nonviolence, the publication behind this podcast. Earlier this month, we celebrated our 10 year anniversary at a small event here in Brooklyn. It was great to see so many of our friends, writers and supporters all in one place. That’s not something we get to do often. What you might not realize — even if you’ve been a longtime follower — is that we do our work remotely, not in some bustling news room. Part of that is because we’re an online media platform — and we don’t have to be in the same place together. The main reason, though, is that we’re a really small organization fueled more by passion than funding. In fact, we don’t even have any big grants. That means we have to rely on more of a grassroots funding structure. And that, in turn, means I have to ask for your help.

If you’ve been enjoying this podcast or any of the work that we do, please head over to wagingnonviolence.org/support and become a sustaining member. By signing up to make monthly contributions, you’ll be helping us plan for the future – a future that needs movement media. And right now, at the $5/month level you can get our brand new T-shirt or tote bag plus another gift. This T-shirt and tote feature a pretty unique design that pays tribute to the movements — both historic and present — that have informed our work. If you want to see what it looks like, again, head over to wagingnonviolence.org/support. You can also make a one-time donation there if you prefer. All contributions are tax deductible.

So, thanks in advance to anyone who can help us get our second decade off to a strong start.

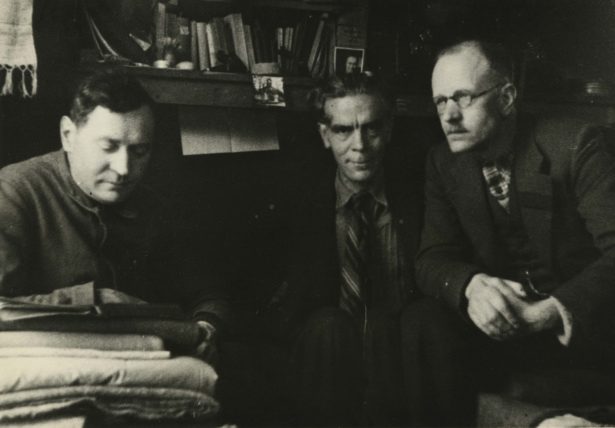

Daniel Trocmé was André’s younger cousin. And just like André, he came from a wealthy educated Protestant family in the North of France. Even more like André, though, he was idealistic and courageous.

Patrick Henry: He’s someone actually whose story should appeal to today because we talk a lot about white privilege, and Daniel saw himself as the son of privilege.

That’s Pat Henry, who you may recall from the first episode. He’s the author of one of the books on Le Chambon, called “We Only Know Men.”

Patrick Henry: Daniel would write letters to his parents and say “Western civilization is only one civilization.” “I can now see the beauty of Christianity, but also its ugliness.”

Daniel’s parents wanted him to teach at his father’s prestigious private school and one day take it over.

Patrick Henry: And all of a sudden he writes this letter to his parents: “The die is cast.”

This meant he was going to go Le Chambon. To accept his cousin’s offer of running one of the children’s homes. It was October 1942.

Patrick Henry: He’s breaking away from his parents. He’s going to stand up and do what they don’t want him to do. He says, “This is going to be the work I’m going to do for the reconstitution of the world” and “I’m choosing it so that later on I won’t be able to say I’m ashamed of myself for not having chosen it.” Kind of a beautiful thing. Guy’s only 32 years old.

Like the other children’s homes in Le Chambon, the one Daniel took over had a name: Les Grillons or The Crickets. And one of the children in his care was Peter Feigl. But, as a 13-year-old, Peter recalls not fully appreciating Daniel’s dedication and sacrifice.

Peter Feigl: I think the greatest injustice that I did him was when, in the Springtime, he presented us with a pair of sandals, which he had fabricated from old automobile tires. And I rejected them and said, “You don’t really expect me to wear such hovel things?”

Shoes were quite hard to come by during the war. So, Daniel was fashioning them by hand from scraps — just to ensure no child would be without a pair.

Peter Feigl: I didn’t realize how much of an effort, how much work it was to cut up old tires and turn them into sandals. So, I was an ingrate, obviously.

Daniel did one other thing that Peter didn’t fully understand or appreciate: He took his diary — a diary Peter had been keeping since his parents were arrested.

Peter Feigl: He saw that it contained names of people, dates, location and so forth.

And he knew that if it fell into the wrong hands…

Peter Feigl: It would be curtains for a lot of people.

Daniel now had a lot of people in his care, having taken on the duties of running a second home called La Maison des Roches, or The House of Rocks. It had previously been run by an older couple, but they found the work too overwhelming — especially as the threat of raids increased. What’s more, the House of Rocks was a riskier place to be in charge of. Rather than sheltering small children, it housed young men aged 17-35.

Patrick Henry: So, André Trocmé asked Daniel “Would you take over that one?” And he agreed to do that one as well.

But it wasn’t long before the House of Rocks ran into some trouble. While there are conflicting reports of what happened next, it seems some German military police stopped by one afternoon in late April 1943. They were searching for an army deserter and while they didn’t find him at the House of Rocks, they found enough to make them rather suspicious.

Patrick Henry: It was probably impossible to go in that house and look around and not realize that half of these people or more were Jewish.

Regardless, the Germans left that day with the House of Rocks squarely on their radar. There are differing versions of what happened next, but the basic gist is that they returned a month later and arrested someone by the name of Ferber. It’s unclear if he was Jewish or another deserter.

Patrick Henry: I have no idea how he got there and I have no idea how the Germans found out he was there. But they got him out, and then they were gone.

This was a dangerous situation for everyone because the Germans now had someone they could press for information. Some of the men living in the House of Rocks left in search of other places to hide, but the majority stayed behind. Why? Again, there are varying accounts. Some claim that Daniel was naively over-confident and counseled them to stay put, despite people in the village urging him to do otherwise.

Patrick Henry: They say that the resistance knew that there was going to be a raid. Well, why didn’t the resistance do something?

And so, on the morning of June 29, 1943 — two months after their first visit to the House of Rocks — the German Gestapo showed up to raid it. Twenty-three of its 36 residents were home and immediately ordered to assemble downstairs in the dining room, where they would be interrogated.

Daniel, however, was not there. He was sleeping at the other home he administered, the one called The Crickets. So, some of the Germans went over to go fetch him. When the children at the Crickets saw the Gestapo, they woke Daniel up and tried to get him to escape out the back door to the nearby woods.

Patrick Henry: No one wanted him to go back to that house because they figured he’d get arrested along with them. But he said that morning “I’m the head of both of these houses, and I’m responsible for them so I’m going back there.”

When Daniel left with the Gestapo, someone from The Crickets biked down to the Trocmés’ house to tell them what was going on with their cousin. But only Magda and her son Jean-Pierre were home. So she quickly jumped into action.

Magda Trocmé: I grabbed my bicycle and raced to the House of Rocks.

Several German police with machine guns were stationed outside, when she arrived.

Magda Trocmé: Why did they let me in? I don’t know. I left in such a rush that I hadn’t taken my apron off. Maybe the Germans thought I was one of the staff.

Once inside, Magda saw Daniel and all the young men lined up against the wall in the living room.

Magda Trocmé: I tried to approach him, but a Gestapo man shouted at me.

She turned around and decided to go back into the kitchen, where she sat down and tried to think of what to do.

Magda Trocmé: Then the students started to walk past me, one at a time, into a little storeroom at the back of the kitchen.

The Gestapo demanded each student identify themselves.

Magda Trocmé: When they walked back, some of them had black eyes and all of them looked badly frightened.

The Germans were hungry, and thinking Magda was the cook, they demanded some food. So she prepared a quick breakfast of eggs and bread. While serving them, she managed to talk to Daniel for a quick moment. Here is an actor reading what he told Magda.

Daniel Trocmé: “Remember how a student from this residence, a Spaniard, saved a German soldier from drowning in the river? Here’s what you should do. Go to the hotel, where the German soldiers are stationed and tell them what is happening here. Remind them about that rescue. Who knows? Maybe because of him we’ll be safe.”

Magda had no trouble leaving. She got on her bike and rode into town, to the hotel Daniel had mentioned. Once there, she managed to argue her way into a meeting with several officers.

Magda Trocmé: “I want to know which of you remembers a German soldier who nearly drowned, but was saved by a student from the House of Rocks?”

One of them said he remembered. So Magda began to explain what was going on. The Germans, however, didn’t seem too interested. They told her they had nothing to do with the Gestapo. But Magda could be persuasive— and perhaps because they knew she was an important figure in the village — two of them decided to go with her back to the House of Rocks.

Magda Trocmé: It must have looked very strange for the villagers to see me walking with a German on each side [of me].

But Magda wasn’t concerned about appearances. She was worried they wouldn’t make it back to the House of Rocks in time on foot. Then, suddenly, she spotted two young women with bikes. She knew them from church and asked to borrow them.

Magda Trocmé: So off we rode, me on my bike riding between two Germans on girls’ bicycles.

When they got to the house, the German officers went off to speak with the Gestapo.

Magda I made them promise to tell the truth, as a matter of honor.

She then tried to slip back inside again, hoping to speak with Daniel, but the guards wouldn’t let her. “Come back in a few hours,” they said. “You can talk to him then.”

Magda went home and waited with her 14-year-old son Jean-Pierre. He was the one who had told Magda about Mr. Steckler’s arrest the previous summer, and the one who had brought him that piece of chocolate. Like his parents, he was always eager to help and insisted on joining his mother.

Magda Trocmé: By the time we got to the House of Rocks, everything had changed.

The students were lined up outside and Daniel was with them. Meanwhile, nearby…

Magda Trocmé: Two or three members of the Gestapo were whipping a young Jewish Dutch boy with a strap, shouting “Jewish pig! Jewish pig!” The atmosphere was horrifying.

Magda was able to approach Daniel, who tried to reassure her.

Daniel Trocmé: “Don’t worry about me. I’ll go with my students. I’ll explain things to them, and I’ll defend them for as long as it’s possible. Please, write to my parents and tell them what happened. I’m not afraid and this is my duty!”

Then, one by one, Daniel and 18 of his students were loaded onto trucks and driven away. Magda and Jean-Pierre were devastated. It seemed none of her efforts had worked. Once back inside the house, however, Magda realized one glimmer of hope.

Magda Trocmé: There was Pepito, the Spaniard who had saved the German soldier. The German officers had kept their word. But my hope, as was Daniel’s, had been to save several, or even all of them.

As it turns out, the Gestapo left behind four other students for inexplicable reasons. So five of the 23 residents present at the House of Rocks that day were safe. But no one knew what was happening with Daniel and the other 18. They could only guess it was bad — maybe even the last time they would see them.

Magda Trocmé: On our way home from the House of Rocks, Jean-Pierre announced: “When I grow up I’m going to get back at them.”

Somehow, amidst the emotion of the moment, Magda held firmly to her ideals.

Magda Trocmé: “Jean-Pierre, you know that we shouldn’t try to get back at people. War might resolve a few conflicts, but it causes many more. You know Papa and his ideas about nonviolence and love for others. We have to understand and forgive. That’s the only way we’ll get anywhere.”

Not everyone will agree with this, of course. Forgiveness in the face of such brutal injustice is hard to comprehend. But that’s the level of commitment Magda and André were operating at.

Magda Trocmé: All Jean-Pierre could say was “Oh, Mama, it’s so awful!” After that, he did not say anything else.

—

In the days and weeks that followed, the plateau made every effort to secure the release of Daniel and the others. Even Prefect Bach made requests for their release. But the Germans would have none of it, making the raid on the House of Rocks the only truly successful Vichy or Nazi raid in Le Chambon during the war.

We’ll talk more about what happened to Daniel in a later episode. But for now, it’s important to note that the raid represented more than just a routine roundup of Jews. After all, Daniel and at least 10 of the 18 other people arrested weren’t Jewish. To the Germans, the raid on the House of Rocks had to be seen as a warning to those plotting resistance of any kind.

And by the summer of 1943, resistance on the plateau was no longer just the nonviolent kind espoused by André Trocmé and Edouard Theis. Groups of young men were flocking to the plateau with an interest in taking up arms. Why? The Germans had enacted a law several months earlier, requiring young French men be sent to Germany to work in its depleted factories and farms. And, not surprisingly, it was highly unpopular. In fact, it was so unpopular that nearly a third of the workers drafted by the Germans — some 200,000 people — refused to go, choosing instead to hide out, flee the country or join the now finally burgeoning French resistance.

Naturally, the plateau and its remote villages attracted many of these young men, and soon an army began to form. But who this army posed a greater threat to — the Germans or the plateau itself — was yet to be determined.

—

On the next episode:

Patrick Henry: She somehow was working to save Jewish people and she never got false papers for herself. She had the most famous Jewish name in the whole god damn country!

Credits

City of Refuge was researched, written and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé are performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Daniel Trocmé was performed by Will Travers.

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured the following songs:

- “Quiet” by Audionautix (license)

- “Laid Back Guitars” by Kevin MacLeod (license)

- “Chant des adieux #2“

- “Waltz for Django” by Wall Matthews (license)

- “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” (a hymn by Martin Luther) performed by Chapel Choir

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

“We Only Know Men” – a 2007 book by Patrick Henry

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth