Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part seven of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part seven of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

In the last episode, tragedy struck Le Chambon, resulting in the arrest and deportation of 18 refugees and André Trocmé’s cousin, Daniel. In part seven, a new threat to the rescue operation emerges, as a French resistance army begins to form on the plateau, wreaking havoc on the local population and making it a target for violent reprisal. André and his co-pastor Edouard Theis are forced to make a tough decision for the safety of the villages and themselves. Meanwhile, we learn what happened to Daniel, as well as another heroic rescuer.

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 7

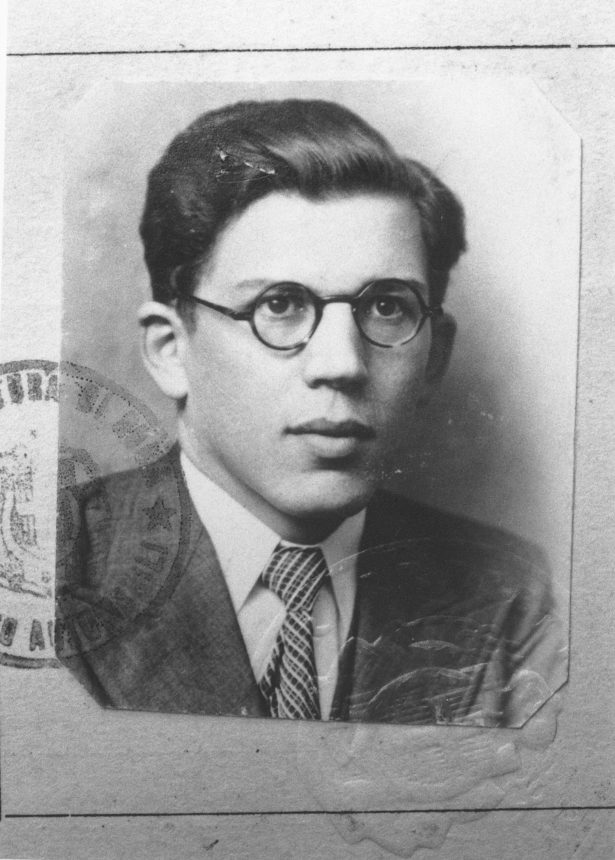

When André Trocmé sat down to write his memoirs in the decades after the war, he had a particular objective.

André Trocmé: My goal is to show that one may go through a war while practicing nonviolence.

And by nonviolence he didn’t simply mean refusing to fight in the war or take up arms in some other way. The kind of nonviolence he was talking about was active. It was everything they were doing in Le Chambon and the wider plateau to resist the Nazi agenda. That included speaking out against it, refusing to cooperate in various ways, and — of course — sabotaging its genocidal plans with a massive rescue operation.

However, by the summer of 1943, it had become a lot more difficult to do this kind of work. For one thing, the Germans had just pulled off the first successful raid in Le Chambon — taking 18 refugees and André’s cousin, Daniel Trocmé. There was no telling what they might do next.

Making matters more complicated was the rising number of armed resistance fighters on the plateau. Their presence put even more of a target on the area — not just for raids, but for actual violent reprisal. The Germans had the ability to wipe out whole villages if they wanted — and that was especially bad given that more refugees were living there than ever before.

This whole situation really troubled André. He worried that the spiritual resistance — with its weapons of the spirit — would just dissolve into the armed resistance.

Magda Trocmé: When we speak of nonviolent resistance in Le Chambon, it doesn’t mean that all the people in Le Chambon were nonviolent.

That’s Magda Trocmé, André’s wife.

Magda Trocmé: It means that they understood the situation of that period. They understood that the Jews were to be saved. It doesn’t mean that it was a conversion to nonviolence or that it was going to last forever.

France was waking up now that the Allies had gained momentum, and nonviolent resistance wasn’t the only kind of resistance anymore. André knew that people would be drawn to join the guerrilla army that was beginning to form on the plateau, but he thought maybe he could stave that off and keep the focus on rescue. After all, he was still a revered and beloved figure in the community.

But then, something totally unforeseen happened. A man, claiming to be a double agent, showed up at his door with serious inside information from the Germans.

André Trocmé: “They’ve decided to put a price on your life,” he told me. “You are going to be assassinated if you don’t go into hiding.”

André was now faced with the biggest decision of his life: stay in Le Chambon and risk being killed or flee and risk letting everything he had worked for the past three years fall apart.

—

After the visit from the double agent, André Trocmé wasn’t sure what to do. He was leaning in the direction of staying in Le Chambon, because he wanted to do whatever was in the best interest of the nonviolent resistance and rescue operation.

Now, it can’t be overlooked that — were André to go into hiding — the armed resistance actually stood to benefit. After all, guerrilla armies need the support of their local community to thrive — and that support is harder to get when one of the community’s leaders is an extremely popular anti-war preacher.

As it happens, there’s actually some evidence that members of the armed resistance concocted the whole double agent story to get André to go into hiding. The evidence is a bit confusing — and at times contradictory — so it’s hard to know what to make of it.

Nevertheless, it seems the double agent — real or not — had limited bearing on André’s decision. It wasn’t until an official from the Protestant Church came to pay him a visit that he began to actually consider going into hiding. They had gotten wind of the potential assassination plot and were worried not only about André’s safety, but what kind of havoc his murder might lead to on the plateau. So, the official asked André, rather bluntly, what good he would be doing anyone by becoming a martyr.

André Trocmé: “I can serve as an example,” I told him. “I have preached nonviolent resistance. I should stick to my post until the end.”

The church official kept pressing, forcing André to picture not just himself getting killed, but his whole family. Then he asked something André had not yet considered: Do you really think your parishioners would stay nonviolent if that happened?

André Trocmé: “No, I don’t believe so,” I replied.

It suddenly seemed there was no good option for ensuring the continuance of nonviolence on the plateau. After mulling it over with Magda, André eventually, reluctantly, decided it was best that he go into hiding. So, in July of 1943, he obtained false papers and assumed a disguise.

At the time, he thought it would only be a matter of weeks before he’d be able to return. The BBC was reporting that an allied invasion would begin that summer, leading to liberation and the end of the war soon thereafter. But that timeline would end up being way off. Victory in Europe was still a good 10 months away.

Meanwhile, André’s co-pastor, Edouard Theis, also saw fit to go into hiding. It’s unclear whether, like André, he was pressured by the resistance or the Church. But, whatever the reason, it was likely for the best. Because decades after the war, evidence of an actual Gestapo hit list was found, and André and Edouard were two of the names on it.

—

The resistance didn’t wait long to make its first big move on the plateau. Just weeks after the two pastors had gone into hiding, a couple of armed resistance men assassinated a Vichy inspector stationed in Le Chambon. The inspector had been living among the villagers for some time, and his job had essentially been to spy and report on them. The resistance obviously saw him as a traitor who had it coming. But, at the same time, the assassination opened the village to reprisals. This was exactly what André had feared — a vicious cycle of deadly violence. Luckily, nothing serious came of it, as no one tried to figure out who had done the killing. Had the inspector been German, instead of French, it would have been a different story entirely.

Meanwhile, thanks to that forced labor law the Occupying Germans had enacted, French resistance armies across the nation were beginning to grow in ranks. Many young French men would rather fight than be sent to work in a German factory. But this presented a problem: They needed food, clothing and weapons. On the plateau, relief came in the form of money smuggled in from Switzerland, as well as parachute drops from the British. Young people like Catherine Cambessédès, who was an older teenager at the time, was among those who helped distribute the goods.

Catherine Cambessédès: Everything was done in secret. You only knew your one step. “Take this to such an address.” And you’d get there and usually there was a password, like “My uncle sends his best.” So then you were trusted to take something or other.

Most of her smuggling work involved money. And she recalls making about five or six trips.

Catherine Cambessédès: I was very scared all the time. So then I stopped doing it because I was too scared. You have to realize I was a big nobody. I was a kid.

Oftentimes, the money and other air-dropped goods weren’t enough. Resistance fighters on the plateau would loot grocery stores, tobacco stores, gas stations — basically anything they needed, they took in the name of the Resistance. They would even steal from the local farmers.

Catherine Cambessédès: They would go to a farm and say, “OK, you are being requisitioned. We need three dozen eggs.” The farmers did not like this.

To make matters worse, they sometimes got farmers in trouble with the Gestapo. In one instance, the Germans killed nine farmers and burned down three farms — all because they suspected them of aiding the resistance in some way. This of course only fanned the flames of revenge. And resistance fighters would strike back whenever they could. But it was nothing compared to the real losses Germany was suffering on the battlefields of Europe.

CBS World News: The new allied landings on the west coast of Italy appear to have put the Germans into a pretty tough spot. Columbia shortwave listening station has heard the British radio report that the Germans are moving large forces back from the fifth army front towards Rome. Russian troops are driving toward key rail junctions near Leningrad, threatening to cut all German supply lines in the North.

When André Trocmé went into hiding, he hopped from safe house to safe house, wherever he or his friends had connections. At first, he was never very far from Le Chambon, but with Magda’s help he was able to move to a more secure location, over 100 kilometers away — far from anyone who might recognize him. He was quite lonely during these months of seclusion, and spent much of the time writing coded letters to his family, as well as the manuscript for what would become his first book: “Jesus and the Nonviolent Revolution.”

Sometime in early 1944, André received word that his son Jacques had been struggling in his absence. So, André arranged to have Jacques come stay with him for a while — a decision that very nearly cost him his life.

André and Jacques were at the train station in Lyon, waiting to catch another train back to the village where André was hiding out. Time was limited, and André had to quickly fetch his son’s luggage on the other side of the station. So, he told Jacques to stay put, while he ran to get the bags.

André Trocmé: Suddenly I found myself nose to nose with a German soldier, his face twisted in anger, his rifle pointed at my chest.

What André hadn’t realized was that a raid was in process. Next thing he knew, he was inside a locked police van.

André Trocmé: Regaining my spirits bit by bit, I sat on the van’s wooden bench and slowly started taking stock of the situation.

His obvious first thought was that his cover had been blown. But then he began to realize they hadn’t yet figured out who he was. Still, it was only a matter time before they did. His fake papers couldn’t be counted on to hold up to intense German scrutiny. He needed to find a way out of this situation quickly if he had a hope of saving himself and his son.

André Trocmé: I signaled the German guard. Thank God I spoke German. He came closer and I said, “My son, a tall, blond 12-year-old boy, is waiting for me to bring the luggage. He is at the top of the stairs in the railroad station. Could you please have someone get hold of him? I need to tell him where he should go because I have been arrested.”

The guard brought over his supervising officer, who asked André why he was running.

André Trocmé: “I was late, and I ran to get the suitcase in a hurry so that we wouldn’t miss the train. Here is the baggage check. You can verify it.”

The officer chastised him, saying “We’re conducting a round-up. Haven’t you noticed the station is surrounded by troops?” André told him he legitimately hadn’t noticed. The officer was skeptical, but told the guard to escort André into the station to find his son and bring them both back. He did not mince words, saying: “If you try to fool the German police, your number is up.”

André Trocmé: I was allowed out of the van and the guard stuck the tip of his rifle between my shoulders. I walked like a robot toward the front of the station, praying that Jacques would still be there. He was, and he signaled to me with great relief.

André explained to Jacques that he had been arrested by the Germans and that they needed to go talk to the police officer.

André Trocmé: Jacques was as terrified as a child could possibly be. We walked back to the officer. He took one look at this child who was beyond himself with fear and sorrow, and his expression changed. He was moved.

The officer told André he was no longer under arrest. Still, he and Jacques would have to go through a security check. The guard was instructed to stay with them while they waited in line.

André Trocmé: At a distance, we saw an officer sitting at a small table. He examined each document for a long time, checking the names against his register of suspects and comparing their faces with a collection of photographs of wanted persons.

André realized there was no way they would make it through this security check. Even if the Germans were fooled by his forged papers, they would see his son’s, which carried the name Trocmé. He had to think of a way out of this.

André Trocmé: The line moved slowly and the guard started chatting with his pals a little distance from us. Pretty soon, he fell behind as we moved forward, a step at a time. I said to myself, “If I can only make it to that concrete pillar between me and the guard.”

Behind the pillar there was an exit that arriving passengers used to get out onto the street.

André Trocmé: “Jacques, do exactly what I do, and slowly, without running. Get ready.” Just for an instant, the guard stopped looking at us. I got out of line and walked only five steps, but it was enough to put me behind the pillar, out of the view of the guard. Jacques followed me, and there was no reaction from the soldiers. I said to Jacques, “Let’s go out of the station slowly with a group of travelers.” And that is what we did, slowly, calmly, with the other people who got off the trains.

Fortunately, the Germans were only checking departing passengers. So it was the perfect escape. Once on the street, they hopped a street car and — since it was Sunday — went to church.

André Trocmé: I picked up a hymnal, and I sang as I have never sung anytime in my life. I had been very close to death, I had even accepted death, but I was free. The only time, perhaps, in the history of the Gestapo that a prisoner, already locked up in a police van, got out without being questioned once or ordered to produce his papers.

André and Jacques stayed with a friend in Lyon that night. Then, the next day, after scouting out the train station to see that the round-up had ended, they caught their train and spent the next several weeks together. It was one of the happiest times during the war for André, as he got to bond with his son in a way that time normally never allowed.

Some years after the war, André found out just how close he had been to capture and certain death that day. Someone with access to the Gestapo’s records in Lyon told him that the Germans had figured out who he was after realizing he had escaped the train station. They also punished the officer who had let him go. This news, perhaps not surprisingly at this point, really bothered André. He hated that he might be the cause of someone’s suffering, even a Nazi.

André Trocmé: I hope that my kind, distracted liberator did not die on the Russian front. He did not deserve that. He was a good man, for the face of a child crying was all it took to stir his heart.

Just a quick break in the story to tell you that Waging Nonviolence — the publication behind this podcast — is in the middle of its annual holiday fundraising drive. We need to raise $20,000 by the end of the year to ensure we can continue to bring you quality storytelling about movements for justice and peace. This series is just one example of our work. Over the course of a year, we’ll publish sometimes hundreds of stories from around the world. In fact, over our 10-year history we’ve published original on-the-ground reporting from more than 80 different countries, including places like Guatemala, Uganda and Syria — where stories of nonviolent resistance rarely get the attention of mainstream media.

So, if you’ve been enjoying this series or any of the work that we do, please head over to wagingnonviolence.org/support and become a sustaining member. When you join at just the $3/month level you are entitled to a gift of your choice. We have some really great books on offer — some of which you’ve heard me talk about in previous episodes. And if you join at the $5/month level you can get our brand new Waging Nonviolence T-shirt or tote bag, which has a really cool design that features 24 different movement icons and logos.

Again, just go to wagingnonviolence.org/support and you can see all the gifts and our easy to use sign-up form. If you prefer, you can even make a one-time donation. Whatever your able to give will be a big help. So, much thanks and now back to the story.

—

Daniel Trocmé wrote to his parents from a concentration camp in Northern France in September of 1943. Patrick Henry’s book “We Only Know Men,” offers a close examination of these letters, which he obtained from Daniel’s family.

Patrick Henry: I poured over those letters. I weighed every word and tried to put myself into his shoes.

One of the things Pat observed was how determined Daniel was to make his parents understand that he hadn’t rejected their values.

Patrick Henry: He wanted them to know that he really wasn’t a rebellious son.

In fact, he saw his work as an extension of what his parents wanted of him, which was to be a teacher. The only difference was he didn’t want to educate the wealthy.

Patrick Henry: He felt he was a privileged person, and he wanted to work with people who were not as privileged.

Perhaps it helped his parents understand better when he asked them to relay a message to the refugee children he had left behind two months earlier. Here now is an actor reading what he wrote.

Daniel Trocmé: Dear children big and small: I think that this separation actually brings us together, because now I understand a little better the adventures that so many of your parents have had. We will thus have many memories in common.”

Then, in closing, he said:

Daniel Trocmé: One of the most beautiful joys that I promise myself is seeing you again. I will will not leave you as long as it is in my power. You can be sure of that.

Patrick Henry: He continued to think that those children were his children. That he had a family.

In December, as the holidays approached, Daniel wrote to his parents again.

Daniel Trocmé: Since I am pseudo-head of a family, you can understand that the children are particularly close to me this season. As Christmas presents, please have 1,500 francs of my money distributed equally among them.

Around the time of that letter, Daniel was deported to Germany, where he spent time in two different concentration camps. In the Spring of 1944, he was sent to Majdanek, an extermination camp in occupied Poland. By this time, an old heart condition had reared up. It was related to having had rheumatic fever as a child.

Patrick Henry: His friends in the camp tried to take care of him. He was thin, weak, very sick. His heart was obviously failing him. He had difficulty breathing. He was in bad shape obviously when they put him in the gas chamber.

It was April 2, 1944 and Daniel was only 32 years old. His family didn’t find out what had happened until after the war. At first, André came to feel that it was his fault, since he was the one who brought Daniel to Le Chambon. But then, he received a letter from Daniel’s parents.

Patrick Henry: They write to him and say, “You know the religious uncertainties of our son, who was still trying to find himself. In giving his life he found what he was looking for.”

They had ultimately, in the end, been persuaded by Daniel himself.

Patrick Henry: They just became more and more proud of their son and what he did.

Despite the tragedy, there’s no indication that Daniel ever regretted his decision.

Patrick Henry: It’s tragic to die that way, but should he have done something different? I’m not in a position to judge. Was his behavior consistent with his principles, yes it was.

—

As the arrest of Jews continued unabated in France, so too did the rescue operation. Social workers were continuing their rescue work, people like Madeleine Dreyfus — who we heard about in an earlier episode. She helped bring young children like Renee Kann Silver and her sister to the plateau. This kind of work meant getting children out of French internment camps, giving them fake papers and hiding them in safer places like Le Chambon.

Patrick Henry: She saved at least 100 children.

That’s Pat Henry again, who also did extensive research into Madeleine Dreyfus’s life.

Patrick Henry: She brought the children from Lyon up to Le Chambon and then they would come and get them and put them in all these different houses. But she also did it in other places.

By the fall of 1943, the work had been taking a toll on her. To make matters more difficult, she was actually doing the work while pregnant.

Patrick Henry: Her husband begged her not to do it anymore. She had three children. What was she doing?

Madeleine finally agreed. But right before she was able to step away, she got arrested.

Patrick Henry: She hid two children in an institute for deaf mutes in the suburb of Lyon called Villeurbanne. And, unknown to her, the head of that institute was also a big leader of the resistance in the part of that area.

So one day, she went to check on those two children.

Patrick Henry: And when she got there, the French police were there.

They had come to arrest the resistance leader.

Patrick Henry: But she got caught in the middle.

While she waited to be questioned, she knew it was only a matter of time before they found out who she was. For one thing, she didn’t carry false papers.

Patrick Henry: Somehow she was working to save Jewish people, and she never got false papers for herself.

Even more incredible, though, was the fact that she herself was Jewish. In fact…

Patrick Henry: She had the most famous Jewish name in the whole god damn country!

Pat is referring to the Dreyfus Affair, an infamous example of anti-Semitism in French history. So, essentially, Madeleine’s name was synonymous with being Jewish in France.

Patrick Henry: People said she was someone who never thought about herself.

Which is why, sitting there, waiting to be questioned, she thought up a plan to save her family. She asked if she could call home, just to let her husband know that she wouldn’t be home in time to feed their newborn. The police acquiesced.

Patrick Henry: So what she did was, she called and left a message like “I’m not going to be here because I just got arrested.” So that anybody at her home would get out, which they did.

Her husband headed straight to the plateau with their three children. Meanwhile, Madeleine was finally brought before a Gestapo agent.

Patrick Henry: The guy looks at her papers and sees “Dreyfus,” and he says “You’re a Jew!”

And he grabbed a pitcher of water and threw its contents all over her.

Patrick Henry: She said, “As if he was going to cleanse me of my Judaism.”

Her only response was to laugh in his face.

Patrick Henry: And he said “You won’t be laughing when you get to the Russian Front.”

Amazingly, they never found out about her rescue work.

Patrick Henry: As soon as they found out she was Jewish they wanted to get rid of her.

And so, she was sent to a French internment camp called Drancy.

Patrick Henry: That’s what the French referred to as the ante-chamber of Auschwitz.

But, as luck would have it, she knew the person in charge of registering people.

Patrick Henry: This guy put her down as married to a prisoner of war. And at that point they were giving special consideration to women who were married to men who were prisoners of war, who had fought for France.

This saved her from immediate death, because those people weren’t being deported right away. It also gave her time to continue trying to save her family. Knowing that they were in Le Chambon, and fearing that it too might be unsafe, she managed to get a coded message to her husband, instructing him to smuggle the children into Switzerland. The message said, “The boys must stop eating ham.” But in French, ham is pronounced “jambon,” which sounds an awful lot like Chambon. And so, the message worked, and Madeleine’s husband got the children to Switzerland. Only a few months later, in May of 1944, she was deported to Bergen Belsen concentration camp in Germany. Amazingly, the Germans still did not know about her rescue work.

—

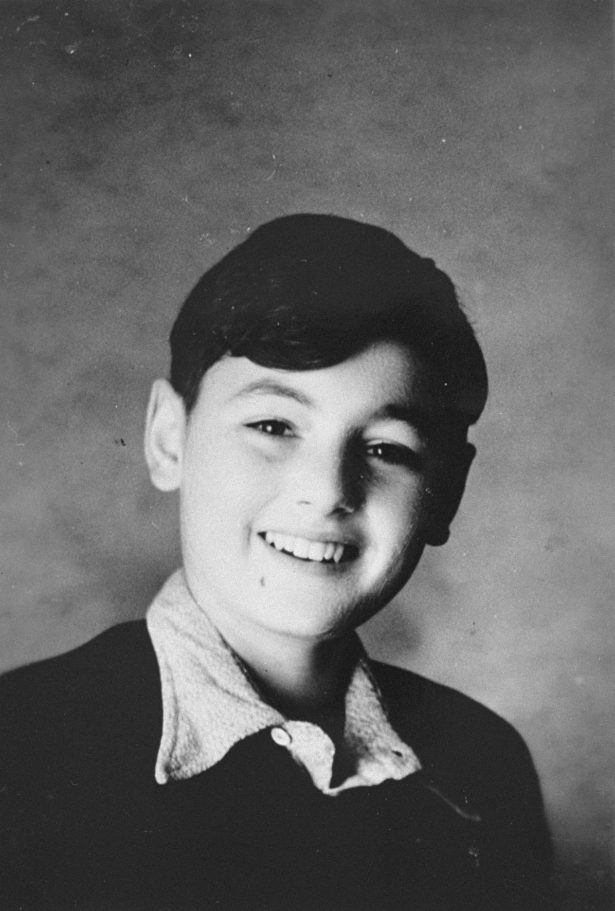

Fourteen-year-old Peter Feigl left Le Chambon and the plateau sometime in the fall of 1943.

Peter Feigl: I think that my being sent away came in conjunction with Daniel Trocmé’s arrest. There was nobody else to take over at that point, and they also were concerned that we might be easy prey.

Peter was given a new identity and some false papers before being sent to a Catholic boarding school in southwest France.

Peter Feigl: The interesting thing about that episode is that I became involved in some resistance activities. The Germans used the schoolyard as a parking lot, and at night a couple of other guys and I, we would scrape together whatever sugar we could find in the cafeteria and the canteen and so on. And we would pour it in the gas tanks of the German trucks.

He also tagged along with actual resistance fighters at one point when they set up bombs in a propeller factory.

Peter Feigl: Shortly after that the Germans then came into town and rounded up all the male citizens between the ages of 16 and 54, I believe it was, and shipped them off to a forced labor camp.

By now, Peter was 15, and he wasn’t going to take any chances. When the Germans started their round-up, he found a good place to hide.

Peter Feigl: I made a bee line for the adjoining church, and I spent the next 24 hours in the bell tower. I could see from there, the troops and the Germans, and I waited until they cleared town and then I came back down again.

Soon after that, in May of 1944, someone from a refugee assistance organization told Peter he was to go to Switzerland.

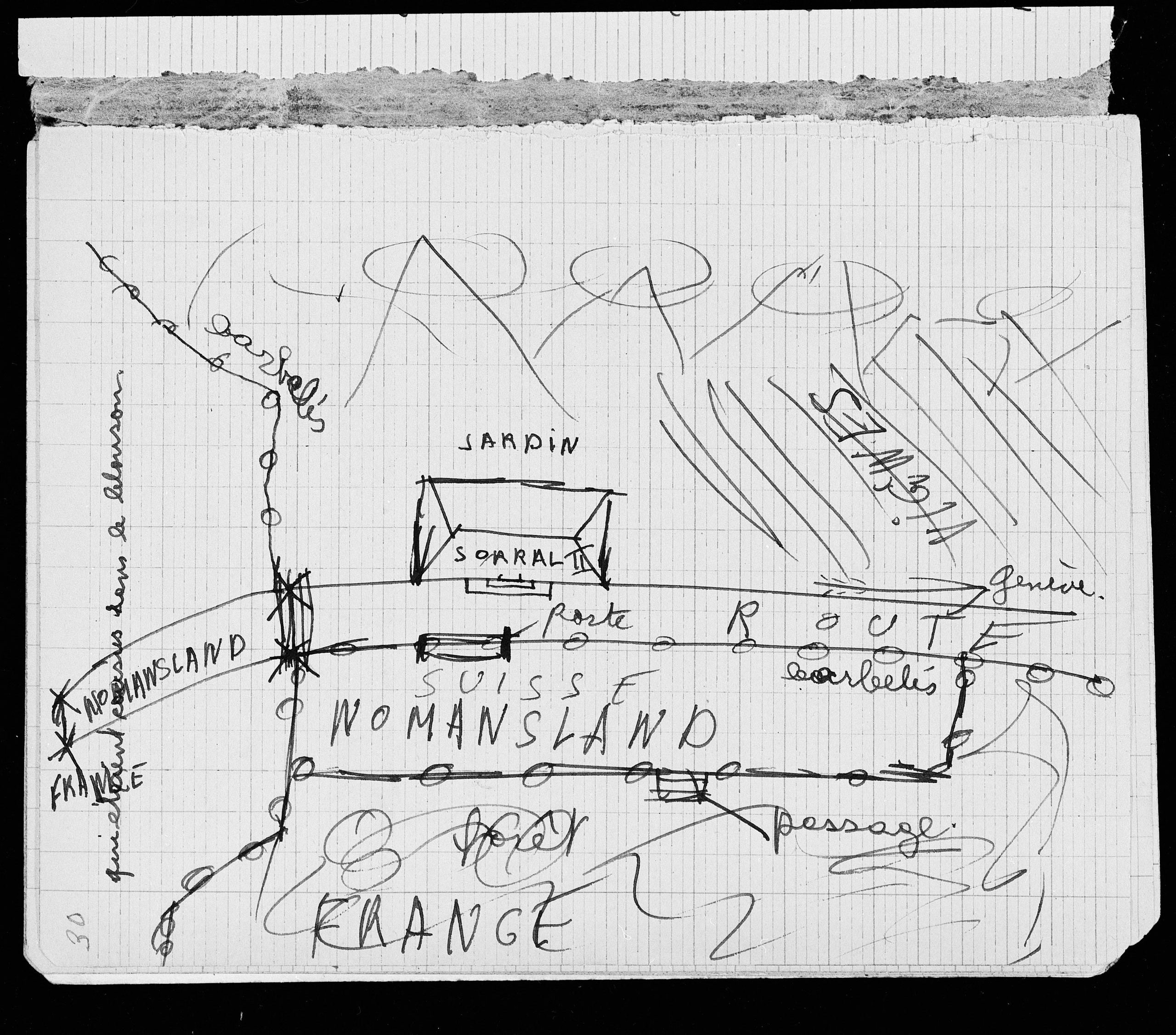

Peter Feigl: I took the train, got off at a small stop somewhere near the Swiss border. I was approached by a young man who told me to follow him. He was a, what the French call a passeur, a border passer.

Peter’s not sure if the man did it for money — as was often the case — or out of the goodness of his heart. But he took Peter and about 10 other children to a spot, where they could see the Swiss guards. They were told to wait until the guards changed shifts to make their move.

Peter Feigl: And so around 1:00 o’clock, I think, afternoon, activity, the whistles, could hear some dogs barking, we said, “that’s it.” And we jumped up, and we started to head for the barbed-wire fence.

At this point, they were not yet in Switzerland, but rather the No Man’s Land between the two countries. Suddenly, he heard screaming and gunfire.

Peter Feigl: I don’t stop, I keep going to the second fence, and as I go up — just about to start the second fence — I see this outline, this silhouette of a soldier standing there. My first reaction was, it’s a German. And then I looked again and I said, no. The, his helmet looked different.

Peter decided to keep climbing. The soldier remained motionless until he was over and his feet had landed on the ground.

Peter Feigl: Then he just motioned to me and said, “Get behind the building,” in French. And now I knew I was in Switzerland.

But not everyone in his group had made it.

Peter Feigl: Apparently, what had happened is that some of the other kids, one a girl, got over the first fence and she saw the soldier who I had seen, and she thought it was a German. So she began to scream, “The Germans are there, the Germans are there.” And during that period, the Germans started to open fire. I think out of a group of about 10 people, seven of us, we made it across.

Soon they were picked up and taken to a refugee center.

Peter Feigl: I remember the drive into Geneva. There were grocery stores and so forth, and I saw things I hadn’t seen in four years — things called bananas and oranges. It was, you know, the land of milk and honey all of a sudden.

By the Spring of 1944, getting children from the plateau into Switzerland was the ultimate aim of the rescue operation. At the forefront of this activity was the French Protestant organization La CIMADE. Run principally by women, the CIMADE began its work in the camps, alongside other aide groups mentioned earlier, like the Quakers, OSE and the Swiss Red Cross. But following the rise of deportations, the CIMADE organized a sort of underground railroad that enabled Jews to escape to Switzerland.

André Trocmé: Hundreds of Jewish people were able to escape.

This is André again.

André Trocmé: And the more Jews who escaped, the better known it became, and the more Jews arrived. While I was gone, Magda and others kept busy finding places for them to live on neighboring farms.

Meanwhile, Edouard Theis actually joined the CIMADE during his time in hiding — becoming one of their few men working with the CIMADE to guide refugees through the mountains and across the border. At one point, while in Switzerland, Edouard wrote a letter to his oldest daughter Jeanne in Pennsylvania. It was the first she had heard form him in quite some time, and there was a rather surprising bit of information he had to share:

Mark Whitaker: He was writing from a jail in Switzerland to say he was alive and well and so forth.

That’s Jeanne’s son, and Edouard’s grandson, Mark Whitaker.

Mark Whitaker: So she knew he was in some danger, but she didn’t know the details until after the war.

Luckily it was only a Swiss jail and Edouard was soon released — just as bigger things were around the corner.

NBC News D-Day: We interrupt our program to bring you a special broadcast. The German news agency Trans Ocean said today in a broadcast that the Allied invasion had begun. I repeat, the German news agency Trans Ocean said today in a broadcast that the Allied invasion had begun.

This was the early morning news on June 6, 1944, otherwise known as D-Day. The start of the liberation of Europe had begun. And the resistance fighters were ready to play their role, which was to stop the German reinforcements from reaching the front in Normandy. But on the plateau, things didn’t quite go so smoothly or heroically. Once again, there were more cases of armed robbery, with guerrilla fighters holding up farmers, shop keepers and even town halls. No doubt, they were strapped for food, but so was everyone else.

Then, on June 9, in the plateau area, they fought their first battle against the Germans. It was a brutal endeavor, with the resistance fighters outnumbered five or six to one. By the time they had been ordered to retreat three days later, the resistance had lost 260 men with a further 160 wounded. What’s more, there was no decisive winner — only the sense that the Germans were not done fighting.

Still, a few days later, André felt safe enough to return from hiding. He had expected to only be gone a few weeks. By this point, it had been 10 months. And what he saw in Le Chambon was a different kind of village.

André Trocmé: The underground is no longer hidden. Young people parade in the streets dressed in odd pieces of uniforms, with machine guns in their hands.

Some of these young people had been students at the Cévenole school, which he and Edouard had founded right before the war. A few were even part of the youth contingent that stood up to the Vichy official Georges Lamirand two years earlier. In other words, the nonviolent city of refuge he had left behind was now like much of France — filled with a sense of revenge and utter confusion. So, it was with a heavy heart that André spoke from the pulpit for the first time since returning.

André Trocmé: We have come to know, bit-by-bit, war in all its forms, and we are now cast into the furnace with the rest of the country. However, our little difficulties are nothing compared with the problems in burnt and bombed cities and in those places where fighting is still going on.

Nevertheless, as he explained, they were all facing their greatest tests yet.

André Trocmé: These coming tests will tell us all what kind of people we are. There will be those who choose the selfish life, who seek to profit from the suffering of others. And there will be those who will instead allow themselves to be swept up by a spirit of enthusiasm, sacrifice and devotion.

While he certainly was pushing them toward the latter, he made one final plea in that regard — one that echoed his “weapons of the spirit” statement four years earlier.

André Trocmé: The true Christian does not seek an earthly kingdom. He seeks the kingdom of God. He does not use, in the fight against all forms of evil, the earthly weapons of violence, lies and vengeance.

Then, in conclusion, he added some words of encouragement:

André Trocmé: I have been happy to see, from the day of my return, that you have all stayed calm and steady. A spirit of moderation and gentleness should now reign among us.

There’s no doubt André was trying to wish, if not will, a return to the spirit of nonviolence. And with his own return, followed soon by that of his co-pastor Edouard Theis, such an outcome might have even seemed likely. But what no one knew was just how difficult things were about to get.

—

On the next episode:

Hanne Liebmann: It was a beautiful sunny day, and here were the Alps in full sunshine and I felt totally drained. It was not “Hooray the war is over.” We had lost everyone and everything.

Credits

City of Refuge was written, edited and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé were performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Audio of Peter Feigl was derived from this interview conducted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in August 1995.

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers, who also voiced Daniel Trocmé.

This episode also featured the following songs:

- “Quiet” by Audionautix (license)

- “Laid Back Guitars” by Kevin MacLeod (license)

- “The 49th Street Galleria” by Chris Zabriskie (license)

- “Waltz for Django” by Wall Matthews (license)

News clips came from the following sources:

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Hidden on the Mountain” – a 2007 book by Deborah Durland DeSaix and Karen Gray Ruelle

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

“We Only Know Men” – a 2007 book by Patrick Henry