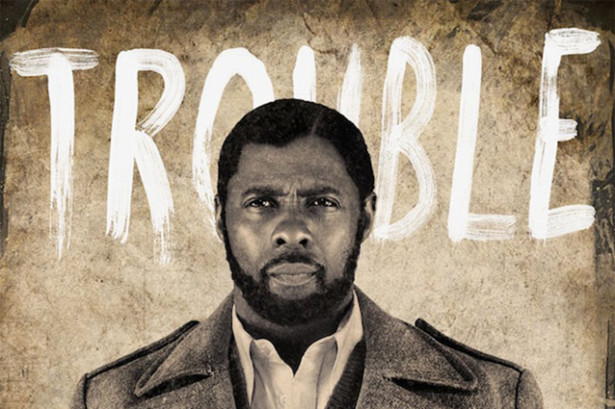

Given the ongoing and important discussions this past month on how best to commemorate the legacy of Nelson Mandela, it seems necessary to separate fact from fiction in the recently-released Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. While the film contains some wonderful acting — on the part of Idris Elba, Naomie Harris and others — it also has some serious misdirection from a political point of view. Here are four vital corrections which must be clearly understood – especially if one wants to emulate Mandela and help build movements like the one he led.

1. No one person, or even a single organization, can create a movement (or change history) alone. Mandela was always clear that he served as both president of and also subject to the African National Congress, a group which was founded six years before Mandela was born. Mandela believed — as did Gandhi and Steve Biko, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and Winnie Mandela and all their peers — that belonging to and building up an organization was absolutely key to any meaningful, lasting social change. Whether large or small, united front or ideologically pure, all struggles require organized groupings of very committed people accountable to one another if an impact on the status quo is to be had.

Mandela tells its viewers that the ANC had a history before his articulate and strident voice came to the fore, but it would have done better to show that the reason the man was so attractive in his early life was because he and his friends were the cutting edge youth. Fifteen years before the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, which became the ultimate turning point away from nonviolence, Mandela chaired the ANC Youth League, exciting massive numbers of followers because of its creative use of civil disobedient acts against the pass book laws in a manner based exactly on the techniques Gandhi had previously used.

ANC elders at the time, especially ANC President Albert Luthuli, championed civil disobedience (which was often led by women), but Mandela became the fiery spokesperson whom the youth of the organization could rally around. Together, the generations convened the 1955 Congress of the People, adopting the basic demands that 50,000 activists had gathered from grassroots communities in every part of the country. Participation in these fundamental mass campaigns, more than any speech or his position on armed struggle, catapulted Mandela to top leadership.

2. The African National Congress was always committed to united work between Africans, Indians, “Coloreds” and whites. Suggesting that Mandela played any special role in forging reconciliation between black and white is essentially fiction; the very basis of the Congress of the People, for example, was to bring together the African Congress, the Indian Congress and the Congress of Democrats in a broad call for “the people” — all races, ethnicities and tribal groupings — to govern in a unified South Africa. Mandela was friends with Robert Sobukwe, whose Pan African Congress (PAC) later split from the ANC because, in part, it felt that too much was being taken out of the hands of the indigenous Africans. These organizational debates, which took part between wide numbers of people before and after the official banning of both the ANC and PAC in 1960, were always settled on the side of inclusion on the part of the ANC as a whole. Although not emphasized in the film, white militants maintained leadership positions within the ANC both above and underground.

3. Violent tactics which were part of the armed struggle were exaggerated and unduly emphasized. It is striking that most incidents of violence during the second half of the film are perpetrated by African activists. It is especially disturbing that the balance sheet of vicious crimes of violence seems equalized in the movie, when the truth is that the apartheid state engaged in all manner of violence on an extraordinarily unequal level to that of the liberation movement. It is not simply that one side was more committed to justice than the other. Despite decades of unbearable provocation and what many still believe is more than enough validation to be involved in armed self-defense, the liberation movement was also unequivocally and disproportionally more committed to peace than the other.

Mandela remained behind bars chiefly because he consistently refused the admonitions of the apartheid regime that the ANC give up the armed struggle. But the massive unarmed civil campaigns of the ANC, PAC, Black Consciousness, Azanian and other liberation supporters throughout the world and within South Africa took place from the 1960s through to the “one person, one vote” elections of 1994 — and clearly played a major role in the dismantling of apartheid.

4. The role of “black-on-black violence” portrayed at the end of the film is exaggerated out of all context and factual accounting. There can be little doubt that violence existed in South African society in the years leading up to the country’s first democratic elections. Stories and studies about this violence, and the fact that some of it included acts of violence within the African communities, suggest an array of causes and contributing factors. The movie Mandela lays most of this violence at the hands of youthful radicals who are angry that the negotiation process led by Mandela was going too slow. Mandela appears to be leading the negotiations against the wishes of the youth, the advice of Winnie and even the urgings of some of his peers among the ANC elders.

Much of this, in the way it is portrayed, is simplified fiction. The so-called black-on-black violence which did take place was not based on splits, strategic or otherwise, within the liberation movements. In one specific portrayal of confrontation between Mandela and younger activists, Patrick Lekota is seen as an imprisoned youth arriving at Robben Island, criticizing Mandela and his graying comrades for having lost touch with the movement beyond the prison walls. In fact, Mandela maintained his greatness in large part because Robben Island became the ultimate training ground and incubator for post-1960s South African resistance movements. Lekota was released from prison before Mandela, and became one of the foremost leaders of the nonviolent United Democratic Front which voiced ANC politics in the decade before the ANC was unbanned.

Most importantly, the South African Broadcasting System speech where Mandela says “no” to violence and tells the people to forgive whites — one of only two speeches which Mandela spotlights — is a complete fabrication. After the 1992 Boipatong Massacre, when the urge for revenge against the racist regime was perhaps strongest, Mandela made no major television appearance, but rather blamed the white government for fomenting and being the source of the violence throughout the country. Mandela did believe, according to his autobiography, that a cooling down period was necessary, but he suspended the negotiations — not the people’s militancy. Rather than abandoning the progress made by calling for a return to armed struggle, the ANC leadership gave a thumbs up to the Mass Democratic Movement. The apartheid regime at the time suggested that black-on-black violence was one piece of evidence that most Africans — beyond a “special man” like Mandela — could not handle democratic participation. Sadly, this section of the movie does little to contradict that lie.

If we are to be true to Mandela and our other heroes, it is surely time to ask: Does the leader truly make the movement or does the movement make, shape and allow for great leaders to emerge? If, as most historians suspect, a little bit of both is involved in every great moment of social change, perhaps we are ready for mass media that reflects these realities instead of the over-simplifications which disable us. The sum total of a movie which emphasizes violence and de-emphasizes people power makes the building of future movements seem harder than necessary and more discouraging and distant than reality necessitates.