The script handed down by conventional wisdom is fairly clear: When a few people stand up to protest against an injustice, and police or soldiers hurt or kill them, the movement is crushed. Violence stops nonviolent protest, right?

Then again, many of us have witnessed the opposite: Violence can often spur the movement to become larger and more powerful.

It’s not fully clear why violent repression can have such different outcomes. One possible explanation might be that a small amount of violence stimulates movement growth and a large amount shuts it down — but that’s simply not true. Some nonviolent movements thrive when experiencing heavy repressive violence and others subside in the face of a small amount.

Yes, there are plenty of times when violence does shut down a movement. But the more cases that are published in the Global Nonviolent Action Database (almost 800 now), the more examples we see of repression propelling the movement to victory.

People in the United States are most likely to know about the civil rights campaigns that flourished in the face of violence, like in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963, one of the database’s 50-plus civil rights struggles. But before the 1950s and 1960s there were intuitively brilliant strategists who saw through conventional wisdom.

Researchers are seeking to understand what enables movements not only to withstand violent repression but to use it for their own growth and power. Australian scholar Brian Martin calls repression that doesn’t work “backfire,” while Lee Smithey and Les Kurtz call it “the paradox of repression.” In my book Toward a Living Revolution, I identify things activists can do to make repression boomerang against those trying to stop us.

Many countries, many cultures

What strikes me when I read the database is how widespread this phenomenon is. It shows up in many countries, in diverse decades, in movements led by farmers and students, workers and professionals. Here is a sample of them, from across continents.

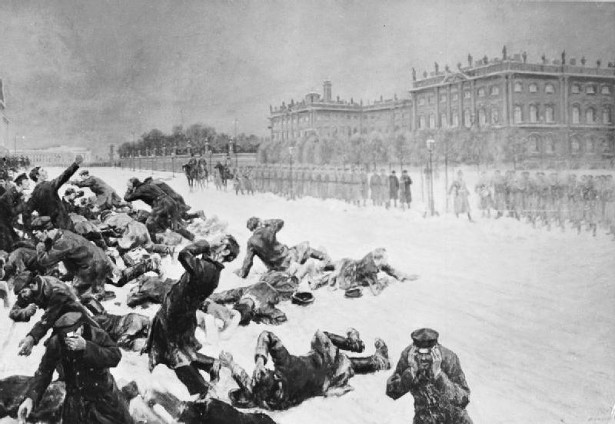

In St. Petersburg, the Cossacks’ massacre of nonviolent peasants petitioning the czar in 1905 famously set off a nationwide nonviolent insurrection. The protests laid the groundwork for the overthrow of the czar in 1917.

The 2010 attempt by the Quebec government to quell the students’ campaign to stop tuition hikes resulted in a province-wide battle that mobilized non-students, including the labor movement. The students won.

In 1952 the South African government hit a small nonviolent anti-apartheid campaign with arrests, beatings and shootings, which quickly increased the size of the movement and mobilized its white allies.

In Bangladesh in 1987 the dictatorship ended up killing many but was unable to stop a pro-democracy campaign. When the government closed the universities to deprive students of their organizing base, more students joined the movement. Lawyers and doctors joined the workers already in the streets. The opposition movement mushroomed, and by 1990 police were refusing to fire on the unarmed crowds. The regime fell.

A similar story played out in Iran in the 1977 campaign against the shah, who led one of the most powerful military forces in the world as well as a hated secret police corp skilled in torture. The campaign began on a small scale with students. Police killed two theology students in a demonstration. That’s when the movement should have shut down in fear. Instead, far more people joined, including non-students. Dramatically, the rhythm of the campaign became driven by 40-day cycles in which mosque services honored the increasing numbers of the dead. Killings and torture propelled the nonviolent protests on ever-larger scales until even the oil workers — the “aristocracy” of the labor force — went on strike.

The shah, still hoping that violence would prove more powerful than nonviolent force, ordered his generals to escalate, resulting in “Black Friday,” when helicopter gunships hovered above unarmed Iranians packed into Tehran city squares, raining bullets upon them. In the glare of global publicity of the bloodbath, President Jimmy Carter issued a statement backing the shah, but inside Iran the repression was the tipping point. Some commanders were still willing to roll their tanks over demonstrators in the streets, but the soldiers became visibly less willing to keep shooting the people. The shah had no alternative but to go into exile.

Guatemala’s dictator Jorge Ubico openly admired Hitler, and he proved it when his long-established military rule was challenged in 1944. When women formed a silent, peaceful march, soldiers fired on them, killing schoolteacher Maria Chincilla Recinos, who became the campaign’s first martyr. Workers and middle class people brought the capitol city to a standstill. The movement’s nonviolent character was underlined with the slogan “Brazos Caidos” (Arms at Our Sides); Ubico was finished.

Last year in China a high school student-led campaign shut down a copper plant in Sichuan province that was poised to pollute the city of Shifang. The first demonstrations were repressed: Police beat up the students, used tear gas and stun grenades, and shot at them. Each demonstration grew in numbers, and soon tens of thousands of people arrived at the site of the demonstrations. Faced with a situation spiraling out of control, the government gave in and agreed not to finish building the factory.

In Japan the Sunagawa farmers took the leadership in 1956 to defeat the planned expansion of a U.S. military base. When police beat villagers with clubs, injuring over 200 of them, 4,000 people showed up the next day to reinforce the demonstration. The police brutality mobilized even members of the Japanese Parliament, who joined the direct action. This did not prevent the police from trampling, kicking and poking at the eyes of demonstrators, injuring over 700 including medics and reporters.

Instead of being deterred by the brutality, thousands more Japanese joined the action at the air base, doubling the number. That was the tipping point. The U.S. military canceled the expansion program.

Which side will learn from history first?

As the examples of unsuccessful repression pile up from all over, the 1 percent’s enforcers as well as activists are trying to understand the upside-down world coming into view. Whatever happened to Mao’s dictum that “political power grows from the barrel of a gun?” That old assumption is still believed widely in popular culture, and across the political spectrum, from the Very Old Left to President Obama to the right wing. However, some thoughtful wielders of state power are questioning it.

I notice that already in some cities in the United States it’s not easy for activists to get arrested by increasingly sophisticated police forces. How disorienting! Rather than developing more creative tactics or escalating the conflict to a new level, though, some activists simply resort to crazy stuff to force arrests — and make themselves look, well, crazy.

But history is full of examples we can learn from of how movements have kept their focus and fought through violent repression to victory. Each side — those responsible for stopping movements for justice and those of us building those movements — has an opportunity to learn from the rapidly-growing people’s history of struggle. We’ll see who learns the most.

My partner and I stumbled over here from a different page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to checking out your web page repeatedly.|