As many as a dozen men detained at the for-profit Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash., are entering their second week of a hunger strike to protest record deportations and the abysmal conditions inside the center.

On Tuesday, hundreds of family members and supporters gathered at the center to stand in solidarity with the hunger striking detainees and to call for an end to deportations. Among them was Rocio Zamora, whose son, Alan Zamora Yañez, had been held in the facility for four days before being transferred to New Mexico to be deported.

“He’s my only son,” said Zamora. She explained that he had come to the United States as a child, and that he had been issued a deportation order despite having valid work papers. “He wasn’t able to talk to a lawyer. The police told him he has no rights,” she said. Zamora wasn’t allowed to see her son before he was transferred.

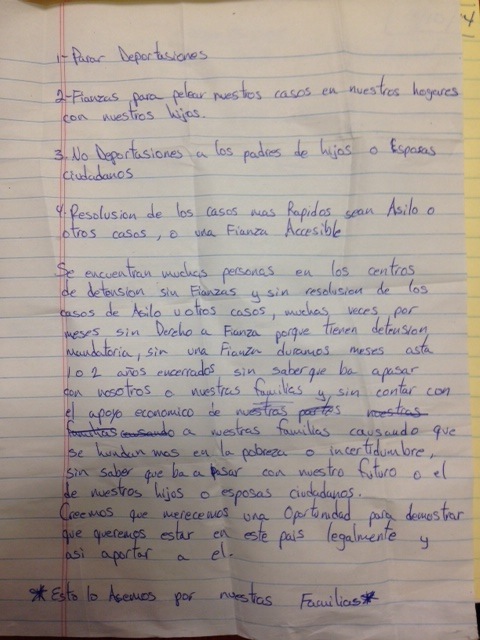

The hunger strike began on Friday, when hundreds of the detainees at the Tacoma facility refused meals and issued a set of demands that included fair pay, better food and an end to deportation. On Monday, the detainees released an updated list of demands that included an end to deportations, particularly of parents; bonds to fight cases from home; and the quicker resolution of cases.

Detainees said they were inspired to launch the strike after activists from the #Not1More campaign blocked deportation buses leaving the facility on February 24. Actions against ICE detention centers have swept the country over the last six months as an increasing number of migrant justice groups have shifted to using direct action to demand an end to the record high deportations.

The current hunger strike at the Northwest Detention Center also follows a series of hunger strikes at other U.S. prisons to protest the deteriorating conditions and human rights violations inside these facilities. Last summer, as many as 30,000 prisoners incarcerated in the California prison system went on a hunger strike to protest the policy of solitary confinement. Although inmates protested for two months, the strike ended without any real concessions from the prison system. Inmates held at the Guantánamo Bay prison also launched a hunger strike last summer, which resulted in dozens of prisoners being force-fed against their will.

Retaliation and abuse

Inside the Northwest Detention Center, striking detainees have faced intimidation and retaliation from guards. On Monday, officials at the facility, which is owned and operated by the for-profit company The Geo Group, stated that they could begin force-feeding those who continue to refuse food.

Detainees who have been identified as leaders of the strike have been placed in solitary confinement, according to Sandy Restrepo and Angelica Chazaro, lawyers from the group Colectiva Legal de Pueblo. Those in solitary are not allowed to exercise, bathe or communicate with others. Other detainees have been threatened with violence by the immigration agents and detention center officials.

“It is a divide and conquer situation,” said Chazaro. She and Restrepo, who are representing some of the men, said that it was difficult to know exactly how many people were on strike since many had been cut off from outside communication.

German Ruvalcaba, a former detainee who spent 18 months inside the facility before being released explained that human rights abuses are common inside the Northwest Detention Center.

“The situation is very shameful,” Ruvalcaba said. “They [the United States] go to other countries to fight for human rights but pay no attention to human rights here.” He explained that he witnessed detainees’ possessions being searched and seized, and guards punishing whole groups of detainees for the smallest violation.

Ruvalcaba said that one of the biggest problems is that he and so many others are treated as criminals when their only so-called crime was to have migrated to improve their families’ lives. “We came to work,” said Ruvalcaba. “A lot of people don’t see that. They see us as criminals.”

Big business

The Northwest Detention Center is one of a growing number of for-profit prisons and detention centers in the United States. Geo Group is the country’s second largest for-profit prison company. It also operates prisons in Australia, the United Kingdom and South Africa. In the United States, Geo Group contracts with ICE to house people whose immigration status is under investigation.

It is a lucrative business — especially with deportations at a record high. The federal government pays Geo Group between $120 and $160 a day for every occupied bed in their facilities. Currently, 1,300 people are being held at the Northwest Detention Center. Most will be detained for about a year while their status is investigated, although others will be held even longer.

A 2011 report from American Civil Liberties Union found that the for-profit prison system needs high rates of incarceration to remain profitable. In a report filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private prison company in the United States, stated: “The demand for our [CCA’s] facilities and services could be adversely affected by … leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices.”

The ACLU report also found that some private prisons have “atrocious conditions.”

Because the private prison industry’s business model relies on having people to detain, Geo Group and others have lobbied to keep the high rates of deportation under the Obama administration. “They are profiting off incarceration,” said Restrepo. “This is why immigration reform has stalled.”

Nearly two million people have been deported since President Obama took office, which is more than under any other administration.

In their letter to the outside world, hunger striking detainees at the Northwest Detention Center explained that ending this deportation pipeline is their core demand.

“We believe that we deserve the opportunity to demonstrate that we want to be in this country legally and to contribute to this country,” the strikers wrote. “We are doing this for our families.”

Hi there, after reading this remarkable piece of writing i am too happy to share

my experience here with colleagues.