In Turkey, in 2013, there was an anti-government protest in Istanbul’s Gezi Park. It grew tremendously, thanks to messages and photos on social media. For those involved, it was an amazing, empowering experience. It seemed to signal a major challenge to the government. But it didn’t last. It was a large protest event, but lacked the foundations to be sustained.

In Turkey, in 2013, there was an anti-government protest in Istanbul’s Gezi Park. It grew tremendously, thanks to messages and photos on social media. For those involved, it was an amazing, empowering experience. It seemed to signal a major challenge to the government. But it didn’t last. It was a large protest event, but lacked the foundations to be sustained.

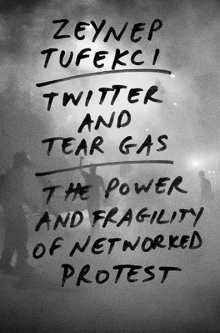

Welcome to the world of “networked protest,” in which social media can be used to bring together thousands of people with remarkably little preparation. To understand how protest organizing has been changed by the rapid uptake of mobile electronic devices, it is valuable to turn to the insightful book by Zeynep Tufekci titled “Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest.”

Tufekci is from Turkey and works at the University of North Carolina. She has spent many years studying the role of media in social movements by participating on the front lines, as well as interviewing activists in Chiapas, Egypt, Turkey, the United States and elsewhere. “Twitter and Tear Gas” is an incredibly impressive account drawing equally on activist experiences and relevant scholarship. Several of Tufekci’s key insights are valuable for improving nonviolent theory and practice, while at the same time her analysis can be strengthened and extended by taking into account ideas about nonviolent action and participatory decision-making.

Organizing then and now

Before the internet, it was, of course, possible to organize protest actions, but it took a lot more effort. Tufekci gives a detailed account of the months of preparation and planning, by dozens of volunteers, for the massive March on Washington in 1963, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Whereas large rallies seem almost routine these days, getting hundreds of thousands of people together decades ago was a triumph of planning and preparation.

In his 1973 book “The Politics of Nonviolent Action,” Gene Sharp described the preparation stage of a nonviolent campaign as “laying the groundwork.” As part of this stage, he argued that movements needed to be ready to handle reprisals because the next stage is “challenge brings repression.” What Sharp didn’t anticipate was that movements could grow so rapidly that they would skim through preparation stages and be unable to take advantage of their opportunities.

One of the features of networked protest that Tufekci describes is a lack of formal leadership. When large rallies are organized at short notice via social media, often there is no agreed upon leader who can negotiate with authorities. The individuals who initiated the action may not be widely known and be reluctant to take a leadership role, while movement organizations are sometimes peripheral to the organizing process. Most importantly, there is not sufficient time for building the personal relationships and decision-making processes necessary for a well-recognized leader to emerge.

In some ways, lack of formal leadership is a positive. Authorities cannot so easily undermine a movement by taking out or co-opting its leaders. Tufekci describes how, in many actions that last for days or weeks, there is a semi-spontaneous system of cooperation to provide food, clothing, medical assistance, cleaning, libraries and other services, largely coordinated by social media. The experience of cooperative living, in which the usual commercial relationships are replaced by altruistic sharing, is incredibly powerful for many participants, giving a sense of the sort of society they would like to create. The emotional impact is increased by the possibility of imminent danger should authorities attack.

New vulnerabilities

While social media enable rapid mobilization of protests and coordination of actions as they occur, they also introduce new vulnerabilities and complexities. Before the internet, movements under repressive regimes had no chance of obtaining mass media coverage and so had to build networks using face-to-face contact, phones, posters, leaflets and newsletters. Today, social media are an alternative to mass media for broadcasting information and coordinating actions.

The problem is that the dominant social media platforms are owned by large corporations, notably Facebook and Google. The advantage for activists is that these platforms are so widely used that authorities are reluctant to shut them down just to target a few activists, because this alienates much of the rest of the population. But activists can be targeted in other ways that are hard to counter.

Facebook has a real-names policy. This may be okay for many purposes, but for political dissidents and stigmatized minorities anonymity can be valuable, because revealing your identity can make you vulnerable to arrest, torture and reprisals on your family.

In 2010, in Egypt, Wael Ghonim set up a Facebook page named “We are all Khalid Said”, named after a young man — not an activist — who was tortured and killed by the Egyptian police. The page attracted a huge following and became a focus for anti-regime sentiment. The Egyptian government wasn’t paying that much attention to social media, but Ghonim’s page was closed by Facebook because he had used a pseudonym. Tufekci tells how the page was only rescued when a sympathizer, who lived outside Egypt, put her name to it despite the risk.

Tufekci provides an illuminating account of the problems posed to movements by commercial domination of online platforms. She provides anecdotes and research findings suggesting that in many cases problems arise not because of government pressure but because company algorithms are applied automatically and snare activist pages, especially ones that other users dislike. It can be difficult for activists to determine whether takedowns of their pages or low ranks in searches or news feeds are due to opposition or to the arbitrary application of an algorithm designed to maximize page views and profits rather than free speech.

Signals and capacities

For assessing a movement’s power, Tufekci draws on a framework based on signals and capacities. Actions by a movement serve as signals to authorities and to potential supporters about the capacities of the movement. She focuses on three types of capacity. The first, narrative capacity, is about a movement’s ability to tell a story that resonates with audiences. Narrative capacity, in the form of framing theory, has been addressed exhaustively in studies of social movements. For activists, a more practical approach is narrative power analysis.

Second is disruptive capacity, which is about being able to challenge business as usual. This is much the same as methods of protest, noncooperation and intervention in the repertoire of nonviolent action.

Tufekci’s third type of capacity is electoral, which is the power to influence outcomes of elections. Tufekci notes that some movements, such as the Occupy movement, do not engage with electoral politics because many participants are skeptical of representative government. So, the example she focuses on is the conservative Tea Party movement, which targeted the U.S. electoral system to great effect.

The final chapter in “Twitter and Tear Gas” explains how governments are learning about networked protest and developing ways to counter movements. In the online domain, it is now usually futile to try to maintain comprehensive censorship because there are so many options to get around controls using social media. Tufekci cites the Chinese government as particularly sophisticated in controlling online discourse. Despite the so-called “great wall of China” to control the internet, the government allows a considerable amount of anti-regime commentary. Where censors intervene is not against criticism but against communication that can mobilize resistance.

One important government technique is to allow dissident communication but to weaken its impact by flooding communication channels with information, so dissent is lost in information overload. Another, related technique is to attempt to reduce the credibility of key dissident voices by spreading rumors and encouraging people to start questioning any source. The result, in many cases, is a disengagement with politics because there seem to be no credible voices, either government authorities or their opponents.

This analysis by Tufekci is a worthy successor to William Dobson’s book “The Dictator’s Learning Curve.” Movements often think mainly of what they are doing themselves and not enough about what their opponents are doing to counter them.

The nonviolence connection

Although Tufekci draws on a wide range of scholarly studies, surprisingly she does not cite or discuss ideas from nonviolent action. Many of Tufekci’s observations and assessments are fully in accord with findings from nonviolence research. What could be added? Two things stand out.

Much of Tufekci’s attention is given to mass rallies and occupations, such as with Tahrir Square in Egypt, Gezi Park in Turkey and Zuccotti Park in New York. These are important, of course, but they receive disproportionate attention because they are highly visible signs of resistance and, by extension, a magnet for journalists. Nonviolence research points to the wide variety of methods that can be used, such as numerous types of strikes, boycotts and alternative institutions. Methods of noncooperation are less publicly visible than mass rallies but can be more powerful.

Tufekci is attuned to the importance of tactical flexibility; indeed, one of her main themes is the inability of networked protests to make decisions, leading to continuation of actions when they have lost their effectiveness. Paying attention to other forms of action would broaden her analysis.

Another key contribution from nonviolence research is the importance of strategic analysis. Rallies, strikes, boycotts and so forth are the methods, but to be effective, methods need to be deployed in a calculated way to build the movement, respond to opponents and, in general, do the most to be effective in the long run. Of course movements are seldom so organized that they can be directed by a few leaders with strategic acumen. Instead, effective movements allow experimentation with techniques — for example, the choice to use or not use humor in different parts of Serbia during the challenge to Milosevic and learning from experience.

Decision-making

Tufekci provides a vivid account of the challenge of making decisions in a large rally or occupation organized at short notice via social media, and where there is a rejection of electoral methods and instead a commitment to nonhierarchical processes. When formal leadership is rejected or challenged, the scene is set for informal domination of proceedings, typically by those who are more articulate and confident, and who sometimes are manipulative.

Tufekci cites Jo Freeman’s famous article “The tyranny of structurelessness”: without formal processes, unspoken hierarchies emerge. However, activists long ago adopted participatory processes, most notably affinity groups and consensus decision-making, which are widely used. One trouble with a rapidly organized action is that there is little time to form affinity groups. Another is that participants may have little experience with consensus processes.

A deeper problem is that affinity groups and consensus processes do not scale up easily. Reaching consensus in a group of 10 is one thing; reaching it in a group of 10,000 is another. This problem suggests the need to develop new decision-making methods for mass actions.

One option is to draw on experience with groups of randomly selected decision-makers in what are called citizens juries or mini-publics. As in a court jury, members are chosen randomly, hear evidence and opinions, deliberate and are entrusted to make decisions in the best interests of the wider community. There have been thousands of trials and applications of this approach around the world, usually with positive results. Participants nearly always find the experience empowering.

Applying the citizens jury model to a protest action requires some advance preparation. One aspect is outlining decision-making processes when the action is organized. Another is that sufficient numbers of participants need some knowledge and experience with citizen jury processes. The implication is that these methods need to be tested and refined in the community, especially in action groups, when pressures are less intense.

Citizens juries are one option worth exploring. The key point is that because there are shortcomings in decision-making in mass actions, there is a need for experimentation with a range of possibilities. Some of these might turn out to be alternatives to the electoral processes rejected by so many activists.

Added value

“Twitter and Tear Gas” is an exceedingly valuable analysis of the conditions for mass protest in the age of social media, and there is much that nonviolent campaigners can learn from Tufekci’s analysis. She highlights the importance of movement building prior to organizing major action. Key aspects of movement building are developing relationships and methods of decision making.

She points to the importance of attention. Traditionally, censorship is implemented by blocking access to information. With widespread use of social media, new techniques are used, including information overload, hoaxes, questioning credibility and harassing social media leaders. These techniques are seldom addressed in discussions of nonviolent action.

Assessments of movement strength need to take into account that it’s now so much easier to organize large rallies. This is relevant to studies comparing the strength of nonviolent campaigns in different time periods.

“Twitter and Tear Gas” is a remarkable achievement, combining personal experience and research to provide insights from campaigners in the age of networks, and presented in an engaging style. For even better value, Tufekci’s insights can be combined with those from nonviolence research and participatory decision-making.

Regarding citizen juries, you might enjoy my novel, long essay, stage play, novella or one of four screenplays on the topic: https://www.amazon.com/David-Grant/e/B0742JFFPP