David Breaux

“What is compassion?”

That was the question David Breaux asked many thousands of people who passed the corner of C and Third Streets near Central Park in Davis, California.

The questioner was a six-footer with hazel eyes and wildly curling hair. He held a spiral notebook in his hand, and if you paused a moment to consider his question — and probe your own experience, consciousness, and awareness to find an answer — he would ask you to write your thoughts in the notebook.

If you asked the reason, his reply was uncomplicated. He simply wanted to know what you thought. Over time, there would be thousands of entries in that notebook.

“Compassion is thinking and feeling and connecting to other living beings with patience, understanding, and caring.”’

“Compassion is understanding and love. It comes from the Latin ‘patio’ and ‘com’ which means “to suffer…with….”

“Compassion is total and perfect acceptance.”

“Compassion is loving. Not loving for the benefit of the self but for others. It is the selfless act of helping others and showing true respect for other human beings.”

Even as passersby pondered his question and shared their thoughts, many wondered who this man was and where he came from.

David Breaux grew up in the city of Duarte in Los Angeles County, California. The family, as described by his sister, was in constant turmoil, with an abusive father and a mother who suffered from schizophrenia. Despite the adversity of his home life, David went on to attend Stanford University, where he developed an interest in filmmaking. That might have become his career, had he not met Karen Armstrong, the former nun and British author known for her insightful books on comparative religion. From her he drew the message that compassion was the pathway to peace. He felt compelled to change his life — giving away all his belongings and taking up a new mission.

In 2009, a friend invited David to move to Davis, near a campus of the University of California, and he took up a constant post at the busy corner across from Central Park and a popular farmers’ market. Without means for steady income, he lived frugally, sometimes staying with friends or sleeping overnight on park benches. As more and more passersby wrote in his notebook — always responding to the question “What is compassion?” — he came to embody an answer to the very question he was asking. With his warm smile and soft-spoken encouragement, released from the time- consuming demands of aspirational living, with unlimited time allowed for listening, he was a patient and compassionate presence in the neighborhood. In time, those neighbors raised funds to build a bench explicitly designed for him. Painted pale orange, with the soft shape and contours of a corner sofa, it was unofficially designated as his permanent outpost.

To some he was regarded as “the second mayor of Davis.” The sobriquet took on new meaning in 2011 when the Davis police used pepper spray against protesting students. Breaux met with community leaders and peace activists, including Rev. Kristin Stoneking, who advocated mediation to resolve the conflict. As Stoneking (then director of the Cal Aggie Christian Association at UC Davis and two years later, executive director of FOR-USA) recalled afterwards, “Each of us had been involved in responding in a way that lifted up compassion… and then bonded over our shared insistence that a restorative justice process be included as a recommendation.” Stoneking and Breaux were to collaborate again in 2014 in planning a “compassion tour” that took him to a number of different cities.

From entries in his notebook, Breaux eventually drew more than 3,000 “definitions” of compassion that he would compile into a single book that he self- published using a small inheritance from his aunt.

Breaux’s life ended at age 50 with an incomprehensible act of violence. On the morning of April 27, 2023, his body was found on a park bench with numerous fatal stab wounds. In the days that followed, hundreds of mourners gathered at “Compassion Corner” to pay their respects and share memories of him. The meaningless brutality of his death only called attention to the message he had taken from Karen Armstrong and so faithfully tried to share — that peace is impossible without compassion.

George Paz Martin

To a 16-year-old boy living on 14th Street in Milwaukee, the prospect of traveling to Washington, DC, was baffling and a little scary. It was the end of summer — August 27, 1963 — and he had just returned from working at the Boys Club when his parish priest, Father James Groppi, pulled up in front of the house in his station wagon. As George hesitated, his mother called out to the young teenager — the oldest of her ten children —“You’re going!” She packed some sandwiches in his gym bag, and before he knew it, he was on the road.

Years later, George Martin recalled why he was so fearful at the outset of that journey. He had never traveled any further than Chicago, and to him, Washington DC was South — a place where (he knew from Jet and Ebony magazines) white men drawled their threats and Black people were segregated, scorned, and mistreated.

On the road, the 16-year-old learned the purpose of the trip as Father Groppi informed his passengers that they would be joining the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” With so little preparation, he was awed by the sight that met him the next morning as his group joined with nearly a quarter of a million people of all ages, races, and colors thronging the National Mall. As he would later recall, it felt like everyone was on their way to a huge game or music concert (and indeed, before the day ended, he would be hearing the voices of Mahalia

Jackson, Pete Seeger, Peter Paul & Mary, and Joan Baez).

How to get the best view? The agile teenager found his way up onto the scaffolding at the Lincoln Memorial. From that vantage point, he was astounded by a vision he would never forget — a crowd stretching as far as the eye could see.

No one seemed to pay any attention to the slight figure clinging to the scaffold. And so it was, that George Martin was less than twenty feet away from the Rev. Martin Luther King when he delivered his famous message promising a better future for the nation and the world — “I have a dream.”

In the years that followed, George Martin faced every form of challenge to that dream as he devoted himself to causes of peace and social justice. Through the decades of his work, he found himself repeatedly asking the question, “What would Dr. King do?”

Returning to his home in Milwaukee after the March on Washington, Martin went on to graduate from Marquette High School and Marquette College, then began working for nonprofits in the areas of economic development, civil rights, unhoused veterans, health care for the homeless, and gang violence. He became a leader in the Green Party, where he was a founding member of the Party’s Black Caucus and in 2001 began serving as Program Director of Peace Action Wisconsin. He joined the national effort to stop the war in Iraq, culminating in a fact-finding mission in 2004, and initiated the Milwaukee Bring the Troops Home Referendum Campaign and the Wisconsin Peace Voter Campaign. Martin also served as National Co-Chair of United for Peace & Justice (UFPJ), the largest peace coalition in the U.S., with more than 1,400 organizations.

Internationally, he worked through the World Social Forum (WSF) for social justice, international solidarity, gender equality, peace, and defense of the environment. His international work for peace led to over 20 trips to Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. A famously dynamic speaker, often called on for interviews, he spoke on radio and TV in over 120 countries. He appeared on every major U.S. television network, including C-Span, CNN, BBC, and “Democracy Now.”

George Martin had been born in the Philippines on March 24, 1946 to Paz and Delmar Martin. He died on July 16, 2023.

James Murphy

When Vietnam Veterans against the War (VVAW) planned their headline protests, united in their opposition to the war that was ravaging southeast Asia, it seemed almost unthinkable that the mistake of Vietnam would, ultimately, neither teach the nation a lesson nor prevent future military intervention by the U.S. government. Yet even as Vietnam faded into history, hundreds of thousands of new recruits were lured into further futile, devastating conflicts.

James Edward Murphy was among the veterans who recognized the absurdity and immorality of Vietnam. But his work on behalf of those veterans did not end with the conclusion of that war. He saw duplicity in the military’s recruiting tactics and recognized the physical and psychological toll that would be taken, generation after generation, from veterans sent to serve a country that did not serve them.

Murphy was an Air Force Communications Specialist in Vietnam from 1964-1968. At the end of his second tour of duty, he returned home with leg wounds, a medal of commendation, a Unit Citation, a Vietnam Service Ribbon, and a Purple Heart. Some three years after his discharge, in April of 1971, Jim helped organize a one-week protest by VVAW in the nation’s capital, setting up camp along the Mall (in defiance of a court order) and attending hearings by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. On the last day of the protest, April 23, nearly a thousand veterans hurled their military badges, helmets, and uniforms over a fence that was hastily erected to “protect” the Capitol. As the rejected tokens of service and patriotism collected on Capitol steps, each veteran stepped forward to bear witness in their nonviolent protest against a ruinous war.

The nation took note. Though the American occupation of South Vietnam — and invasion of Laos and Cambodia — would last another two years, the resistance of veterans who had actually served in the war had profound significance. In December of the same year, Murphy joined with 14 other members of VVAW in occupying the Statue of Liberty for three days, flying an inverted American flag — signaling distress — from the lantern held by Lady Liberty. The visual message was broadcast around the world. America was clearly a nation in distress.

In following years, Murphy became an educator who, in addition to conventional teaching, continued to inform potential recruits about the true nature of military service. After attending the University of Maryland where he studied Special Education and Outdoor Education, he did graduate work in Alternative Education at Indiana University. He taught at the Shon Tai Wilderness School in Virginia, the Hillside School for Children in Rochester and — for 23 years — served as dean of students at the Edward A. Reynolds West Side High School in New York City.

In the summer of 1990, just as the U.S. was gearing up for another war, Murphy became a member of FOR. As he later recalled, “When it appeared that the U.S. was going to engage in another violent and unethical war in Iraq, a few of us older Vietnam veterans were upset and trying to find support for our emotions. As we began our communication and getting the word out, I stopped by FOR in Nyack to see if we could meet there. Doug Hostetter greeted us and made us feel welcome. He even provided us with FOR coffee and the comfort of the ‘Peace Room!’ We grew to 12 members and became the Al Warren Chapter of Veterans For Peace, with Vietnam, Korea, and WWII veterans.” In 2012, Murphy was the recipient of FOR’s Martin Luther King Award.

In retirement, Jim and his spouse Susan, who had helped coordinate the Hudson Valley FOR chapter for several years, moved from Nyack to Ithaca, New York, where he continued to work on behalf of veterans, bringing together a number of organizations to form Ithaca’s Veterans Peace Council. In frequent addresses to high school students, he warned of the false promises extended by the military as inducements to join. He continued his work helping veterans get access to medical benefits denied to them by the VA. His writing group — affiliated with the journal Post Traumatic Stress — encouraged veterans to openly express their many experiences of service, from comradeship and humor to tragedy and loss.

Born September 3, 1945, Jim Murphy died on June 29, 2023.

Gus Newport

On March 28, 2022, more than 400 members of the Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA) gathered for a tribute, hosted by Danny Glover, in honor of the organization’s first president, Gus Newport.

The 88-year-old Newport took the stage in a wheelchair, but his voice was powerful.

“My grandmother is the reason I am who I am,” he told the assembled audience. That grandmother, the daughter of a slave, was born in a little town called Horse Pasture near Martinville, Virginia. One day when she walked in late to her fourth-grade classroom — after a morning picking cotton — her white teacher slapped her in the face. “She walked out of school and never came back,” said Newport.

Newport described how he was influenced by his grandmother’s defiance, her deep understanding of racism, her pride in Black talent and leadership, and her determination to create a better life for her children and grandchildren. Married while still in her teens, she left Horse Pasture for the last time when her wedding presents were seized by the Ku Klux Klan, and moved her family to Rochester, New York, where Gus was born on April 5, 1935. That grandson would go on to create a record of accomplishments — from civil rights activism to visionary community development programs and global solidarity — that would mark him as a preeminent representative of progressive politics.

In Rochester, Newport became involved with community activism while still in high school. Though he dropped out and spent some time doing military service, he was later awarded a scholarship to Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio, where he studied economics and policy. (Decades later, Heidelberg would award him an honorary doctorate.)

While still in his twenties, Newport headed up an influential civil rights organization, the Monroe County Nonpartisan League. When a local mosque was raided by police, he came to the defense of the nine Black Muslim worshipers who were arrested, leading to an encounter with Malcolm X. It was the beginning of a friendship marked by Gus’s early involvement with the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Following a move to California, Gus began working with community programs in the Berkeley city government. Before long, fellow African Americans in the progressive Berkeley Citizens Action coalition convinced him to run for mayor. In 1979, aided in his campaign by Danny Glover and Harry Belafonte, and backed by the coalition, Newport scored an historic victory, becoming the second Black mayor in Berkeley history. He seized the opportunity to carry out progressive reforms in governance and social-action programs. During Newport’s two terms in office, Berkeley became the first U.S. city to divest from South Africa and the first to provide domestic partner benefits for LGBTQ+ families. Newport was instrumental in introducing policies with lasting benefits for Berkeley’s citizens, including rent control, affordable housing, police reform, child care benefits, and environmental protections. During his tenure, Newport allied himself with other political progressives throughout the country, including the then-mayor of Burlington, Vermont, Bernie Sanders. (They became close friends, and Newport later became a leading supporter in Sanders’ presidential campaign.)

Newport’s campaigns for community change and social justice expanded far beyond the boundaries of Berkeley. He participated in the highly successful Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood and lent his support to rebuilding efforts in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Both as mayor and afterward, he expressed his passionate support of international social justice campaigns, condemning apartheid and opposing America’s worldwide involvement in colonization, the shipment of arms, initiation of military conflict, and the use of torture.

Among numerous executive responsibilities, he became a member of the Board of Overseers of the Graduate Program in Community Economic Development at Southern New Hampshire University and served as the Vice President from the U.S. to the World Peace Council from 1980 to 1986. He held positions on two United Nations committees and worked for the Department of Labor, assigned to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In recent years, he focused on influencing the next generation of progressive leaders, mentoring through the National Council of Elders and other organizations.

It was 1988 when Newport became the first president of the Middle Eastern Children’s Alliance, an organization specifically created to protect the rights and improve the lives of children in the Middle East, a post he held until the date of his retirement in 2022. Noting that everyone was telling him he had to slow down, he replied “Death will have to catch me — I am not going to sit and wait for him.”

Gus Newport passed away on June 18, 2023.

Edward Stonebraker

Edward Richard Stonebraker, 63, of Girard, Ohio, passed away suddenly at home on January 1, 2024. As a skilled trades worker, Stonebraker was a dedicated member of the labor movement and a committed ally to diverse social movements, both domestically and internationally.

Stonebraker was born on October 29, 1960 in Youngstown, Ohio, to the late Amanda Lee (Starcher) and Richard Eugene Stonebraker, Sr. He attended public schools and graduated from Girard High School before entering the workforce. Known as “Stoney” to friends and colleagues, he was a laborer who worked as a skilled CNC (computer numerical control) machine operator for many decades with several factories. He was proud to be a part of the United Steel Workers union and was previously a Teamsters member.

A loving spouse and parent, Edward and his spouse of 36 years, Trina (Martinez), took joy in their two children and an expansive family throughout the U.S. and beyond, including Trina’s native Colombia. Their elder child, C (Chrissy) Stonebraker- Martinez, who served as co-chair of FOR- USA’s National Council from 2017-2022, has been co-director of the Cleveland- based InterReligious Task Force on Central America and Colombia for the past decade.

In an emotional tribute to their father shortly after his death, Stonebraker-Martinez wrote,

My father was very supportive of my organizing, activism, and truly my vocational calling. He knew I do my work in honor of my indigenous Emberá ancestors and my working class-farming-laboring Appalachian ancestors from his side of the family. He was my first love and he taught me to love people and love the land. He taught me to be a worker and a comrade (not a snitch, lol), and to be an abolitionist (before we even knew the word). My grief cannot be contained with words. And, my heart feels all that much more deeply for those who have lost multiple family members recently, suddenly, and tragically because of genocide, war, famine, and other systemic injustices. We all universally experience love and loss, and yet it is still a very lonely experience, because it is personal and unique.

C noted that their father believed in both nonviolence and self-defense, which informed their own relentless commitment to liberation of oppressed peoples worldwide. In one cherished memory, Stonebraker- Martinez described giving a speech at a protest and rally in front of the “super-max” prison and immigration detention center in Youngstown, Ohio. Holding a bullhorn and preparing to lead a direct action for migrant justice and abolition, C was flanked by their parents: Trina, like C, wearing a traditional Colombian blouse; Edward holding a handmade sign that said, “We Refuse to Accept a Fascist America!”

Stonebraker enjoyed gardening, relaxing in nature, listening to music, hunting and fishing, playing logic games, watching football, talking religion and politics, and most importantly, spending time with his beloved family and friends over a good meal.

Olive Tiller

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on December 13, 1920, to Otto and Myrtle Foerster, Olive graduated from St. Paul Central High School at 15 and entered the University of Minnesota to study chemical engineering. After being told by an advisor that, as a woman, she would not be employable in that field, she graduated at 19 with a mathematics degree.

The year of her graduation coincided with the beginning of the Baptist Pacifist Fellowship. Olive attended the first meeting in May 1940, and a month later married Carl W. Tiller. They moved to the Washington, DC, area in 1942 when Carl took a position at the federal Bureau of the Budget. The couple became leaders in the Calvary Baptist Church, and Olive became involved with many community projects, including the Prince George’s County Human Relations Commission. She worked at the Kendall Demonstration Elementary School and became proficient in American Sign Language.

Olive Tiller once stated that her four passions in life were “racial equality, peace and non-violence, ecumenism, and baseball.” She became an active participant in many civil rights demonstrations and peace actions, including the 1963 March on Washington, which she attended with her son Bob. Two years later, Olive set up the Division of Christian Social Concern of the American Baptist Convention (ABC), and served on the executive committee of

U.S. Church Women United with Coretta Scott King. She attended the second Selma-to-Montgomery march on March 9, 1965, which was halted by a federal judge’s temporary restraining order.

In 1966, Olive traveled throughout Africa with a bridge-building group of Church Women United, spending eight weeks visiting churches in Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. One of eleven laywomen who opened communication to women in Africa under the auspices of U.S. Church Women United, Olive was arrested at the embassy of South Africa when protesting that nation’s apartheid laws.

Olive and Carl visited the Soviet Union on peace missions four different times. Seeking the end of the Vietnam war, Olive was in a small peacemaking delegation visiting Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, with other World Council of Churches representatives. She later worked with Bosnian refugees.

Joining the National Council of Churches staff in 1981, Olive served as ecumenical officer in the Office of the General Secretary for the ABC. She also became president of the Baptist Peace Fellowship. She also became president of the Baptist Peace Fellowship (now BPFNA~Bautistas por la Paz).

In 1989, Carl and Olive moved to the Sherwood Oaks retirement community near Pittsburgh, Pennsyvania. After Carl died in 1991, Olive spent much of the 1990s in volunteer service, planting trees in Malawi, building houses in Hungary and Tanzania, and teaching English in Italy.

While working with Habitat for Humanity in Tanzania, she helped with funding for the Ulaya Secondary School. The girls’ residence was named Olive Tiller Girls’ Dormitory in her honor.

Those who knew her best described Olive as “sweet, kind, generous, and gentle… but passionate in her fight for justice and equality, and relentless in the quest for peace.” As a close friend put it, “Her smile, which deserved its own copyright, was like a warm blanket on a frosty night. I’m not sure there’s such a thing as being modestly regal, but if anyone could be, it was Olive.”

Olive Marie Tiller died on July 23, 2023 at age 102. Among her last wishes was that friends and acquaintances contribute to the Southern Poverty Law Center in her memory.

Her papers, including archives of the Baptist Peace Fellowship newsletters, are kept by the American Baptist Historical Society at Mercer University Libraries.

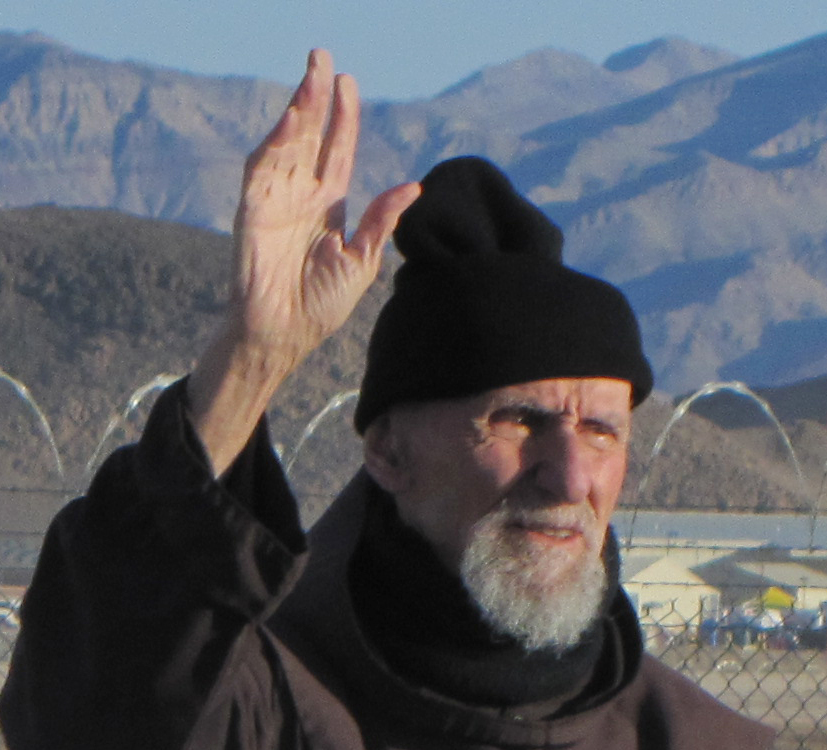

Father Louis Vitale

“There is this deep, deep yearning inside of us for peace — a deep desire to move past a world that’s filling each other with terror fear, debt, chaos — and I think all of us really sense deep down within us that it is going against what we were created to do. We were created to live in

harmony with all people.”

Fr. Louis Vitale spoke these words at St. James Church in Johnson City, New York, in 2009, in a presentation he called, simply, “Love Your Enemies.” That deep, deep yearning for peace was embodied in a man who, for decades, had dedicated his life and energy toward the creation of a better world.

Fr. Vitale was a Franciscan, an order he chose out of his sense of identification with St. Francis of Assisi, who renounced military life and underwent a conversion that transformed him into a man of peace. Vitale’s 20th-century conversion followed a similar path. As a young man raised in an Italian Catholic family, Vitale joined the U.S. Air Force in 1958 in the midst of the Cold War, flying fighter bombers — capable of carrying nuclear warheads — in sorties along the border between the U.S. and Canada. During a routine flight, he received direct orders to shoot down a suspected spy plane without further attempt at identification. The skeptical crew asked for the command to confirm, then reconfirmed. Still doubting the mission, Vitale chose to defy orders and approach the suspicious aircraft on a parallel path. It was a passenger plane.

His trust in the oxymoron “military intelligence” ended there. In decades that followed, during numerous marches and protests, Vitale was unwavering in his defiance of military authority and a loving advocate of social justice. He spent hundreds of days in jail, coming to regard those enforced sojourns as “a journey into a new freedom and a slow transformation of being and identity: an invitation to enter one’s truest self and to follow the road of prayer and nonviolent witness wherever it will lead.”

His arrests occurred in numerous locations: marching and fasting with Cesar Chavez, standing with young men who burned their draft cards, supporting the nonviolent civil disobedience of Daniel and Philip Berrigan. Ever present in his mind, inciting him to join those numerous protests, was his awareness of the dangers of living in a nation with more than thirty-five thousand nuclear missiles prepared to wreak annihilation.

He helped identify the remote desert location of a nuclear test site in Nevada and, in the spring of 1982, joined with members of FOR and other protesters in a 40-day vigil that ended in the arrest of 19 people. Handcuffed and imprisoned, Vitale refused to pay a $100 fine, prompting the judge to order the forcible removal of the protesters. (Vigils involving thousands of protesters would continue, in what became known as the Nevada Desert Experience.)

Following his eye-opening experience in the military and his conversion to the Franciscan order, Vitale earned a doctorate in sociology at the University of California at Los Angeles, served as pastor of St. James Catholic Church in Las Vegas, and became superior of his province (which covered much of the western United States) in the early 1970s. In those years, he recalled, there was a focus on local concerns, including racial segregation and discrimination, welfare rights issues, homeless needs, farm worker exploitation, and the plight of immigrants. He helped create a Franciscan Center, sponsored by the diocese of Reno, to address such needs.

In 1988, Vitale helped launch a Franciscan group called the Pace e Bene Nonviolence Service. As he recalled, “We had become convinced that we not only needed to stop nuclear annihilation but to engage in a revolution in nonviolence that could embrace the world.” In later years, he was made pastor of St. Boniface Catholic church in San Francisco and taught a graduate course called “Liberating Nonviolence” at San Franciscan School of Theology.

His death on September 5, 2023 in San Francisco, at the age of 91, prompted an outpouring of memories from many who shared their own love for the “this great apostle of love.”

As one of his colleagues recalled, “He embodied in our time so many of the 13th century saint’s facets of holiness — an abiding hunger for peace, justice for the poor and excluded, love of nature, and the longing to draw close to the presence of God, including through a contemplative life lived in the midst of the chaos of society.”