Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic and other platforms. Or add the RSS to your podcast app. Download this episode here.

This is part nine of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

This is part nine of “City of Refuge.” To listen to earlier episodes, you can go here or subscribe on the platforms listed above. I highly recommend starting from the beginning.

In the last episode, we experienced the end of the war, the chaos it brought to the plateau, and the silver lining André Trocmé discovered years later when he met with the Nazi official who could have wiped out Le Chambon. In part nine, the Trocmés find new ways to work for peace and justice after the war — all while speaking and writing prolifically about the rescue operation. But it isn’t until a book and documentary come out years later that the story begins to gain widespread attention and even some backlash.

What follows is a transcript of this episode, featuring relevant photos and images to the story. At the bottom, you’ll find the credits and a list of sources used.

Part 9

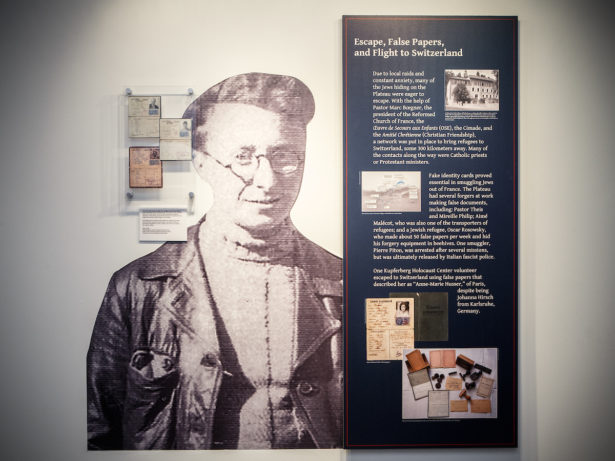

If you’re going to spend a lot of time researching and telling the story of a particular place, it seems only natural that you should go there — and actually see it with your own eyes. Well, as much as I wish this episode were about my trip to France and Le Chambon — I have to confess, I didn’t have the budget for it. Besides, this series isn’t about Le Chambon today. It’s about Le Chambon in the 1940s. So, frankly, I don’t need a plane ticket so much as I need a time machine. Luckily, I found the next best thing: a museum exhibit in Queens.

Cary Lane: We wanted to transport the gallery goer to Le Chambon and feel the significance of this effort.

That’s Cary Lane, curator-in-residence of the Kupferberg Holocaust Center at Queensborough Community College in New York City. And this is him walking me through their Conspiracy of Goodness exhibit shortly after it opened in the fall of 2017.

Cary Lane: We were able to use multimedia to do this, so recordings of sermons from Pastor Trocmé, images of the people who were rescued in Le Chambon, videos of survivors of Le Chambon, including Hanne Liebmann and Renée Kann Silver, who are affiliated with our Holocaust center.

It’s not exactly a coincidence that there’s a Holocaust center in Queens — or that Max, Hanne and Renée live nearby. Many survivors — including my wife’s grandparents — ended up settling in Queens, which still remains a haven for immigrants.

Cary Lane: This is one of the most diverse colleges in the United States. The students are largely immigrants and each of them have their own tangible or real experience with immigration, and I believe 40 percent are below the poverty line as well. So these students know adversity. They know difficulty, and I think this is one of the reasons why this exhibit really resonates.

Which is something that brings Max, Hanne and Renée a lot of satisfaction.

Cary Lane: They’re very heartened by the fact that students are interested in this and they’re learning from this story, especially now in our political environment.

I, of course, was interested in what they thought of the nonviolence angle. Were they surprised? Were they in disbelief? Did they think it was something that couldn’t work today?

Cary Lane: It exposes them to alternative ways to resist, and I don’t think for one second they think that passive resistance is weak. I think they see nothing but strength.

It wasn’t hard to believe what Cary was telling me. The exhibit really was immensely impressive. It flowed down a long 100-foot hallway and had production values that belied its community college environment. I truly felt transported to this place I had been imagining for so long.

Cary Lane: We introduce our gallery goers to the Huguenots’ own experience with oppression and persecution from French Catholics, and we form a sort of thematic basis for this.

The exhibit is, of course, also quick to introduce you to André Trocmé.

Cary Lane: We put an excerpt from the Weapons of the Spirit speech from 1940: “The duty of Christians is to resist the violence directed at our consciences with the weapons of the spirit.” It’s interesting to have the words Christian and Christ in a Holocaust center, but it was so important for us to put in a prominent place how serious these townspeople were about passive resistance.

Aside from André, there are many other familiar figures.

Cary Lane: So this is Peter Feigl and these are his portraits. We call this the Feigl wall.

It’s a collage of headshots, mainly of refugees, that were taken during the war by the document forgers in Le Chambon. Children would often collect and trade the extras, which is how Peter ended up with so many. And amazingly, he held onto them all these years.

Cary Lane: Here’s one example of an actual Oscar Rosowsky fake ID.

Oscar, as you’ll recall from last episode, was the primary document forger — and it’s thanks to his efforts that we know somewhere around 5,000 refugees were sheltered on the plateau — around 3,500 of which were Jewish.

Cary Lane: As you can see it looks like they’re trying to duplicate the same French citizenship card.

Hanne Liebmann gave some of her mementos to the exhibit as well.

Cary Lane: We have her fake identity card, her escape route through Switzerland and the actual satchel that she brought from her home when there were roundups, 78 years ago.

Not only did this satchel survive deportation to France, it survived Gurs internment camp and her escape to Switzerland. It was just amazing to see these items and the people they belonged to treated with such reverence — given how surprisingly little-known the story remains.

Cary Lane: There’s something about that plateau that’s sort of hidden away, I think. So too is this story hidden away, but I think it’s coming to light a little bit more now.

Of course, the only reason a story can come to light 75 years after the fact is if people preserve it and carry its ideas forward. And that’s what we’re going to explore in this episode: How the story was kept alive in the years after the war, how it has evolved over the decades, and its effect on those closest to it.

This is the story of the story of Le Chambon.

—

After the war, the Trocmés and Theises finally had time to think about the future and their plans for it. One of their top goals was to more firmly establish the Cévenole School as a “international center of peace.” During the war, it had served the important role of providing education, as well as cover, for the many refugee children hiding on the plateau. In fact, by 1944, as many as 350 students were attending. The only problem was that the school didn’t have a building of its own. Classes were scattered around the village, wherever space could be found.

So, in the fall of 1945, André Trocmé and Edouard Theis decided to raise money for a building. To do that, however, they had to go to where the money was.

André Trocmé: America: the land of miracles from which we have been separated by six years of war and poverty. America, which has marched forward with giant steps, while we, in France, have slid backwards.

As they traveled the country speaking at churches and universities, they began to tell people their incredible story for the first time. This included their own loved ones.

Mark Whitaker: And so he came to Swarthmore, where my mother was in college at the time.

That’s Mark Whitaker, talking about his grandfather Edouard Theis.

Mark Whitaker: He told the story of what had happened in Le Chambon and so forth, and this was the first time my mother had heard all the details, and she looked around and she saw all these people with tears in their eyes. It was really at that point, surrounded by all these Americans who she had spent the war with, that she really learned for the first time, what a hero he had been.

As Edouard and André had hoped, these awestruck Americans were eager to help the pastors carry their vision for the Cévenole school forward. Students, in particular, volunteered their services.

André Trocmé: So many young people dream of coming to help us create something new and beautiful. “Give me something useful to do,” they sigh. “Let me be part of something bigger than myself.”

Meanwhile, funders and fundraisers also presented themselves. Many were Protestants, connected to the various denominations that had helped fund rescue work during the war — like the Quakers, Presbyterians and Unitarians. By the time André and Edouard had returned to the plateau, they were feeling — for the first time in a long time — energized about the future.

André Trocmé: Right now, I, André Trocmé, am a happy man. I am dreaming of the Cévenole school, which will be nestled at the foot of a mountain. I am happy because I am watching that dream become a reality.

By the summer of 1946, enough money had been raised to start building the school. And over the next few years, many young people from the United States and Europe came to the plateau to help with construction.

Nelly Hewett: We had a great time. It was like a Peace Corps.

That’s Nelly Hewett, André and Magda’s daughter, who spent one summer as a volunteer. It was actually after she had moved to the United States to learn English and eventually go to college.

Nelly Hewett: I left in ’47 — I was so overwhelmed and saturated with all these things that I wanted to get away and discover the world. Just like my parents came to New York to discover the world and get away.

Surprisingly, her parents were being pushed in that direction as well. Despite their interest in the Cévenole school — not to mention all they had done during the war — the Protestant Church in France was once again giving André a hard time.

Nelly Hewett: Ministers last only that long in a church. You are never a minister for 50 years in a church. You get tired of each other and so forth and so on.

Specifically, the church hierarchy in France was tired of André splitting his time with the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, or IFOR as it’s known. So, his tenure as pastor in Le Chambon basically came to an end, allowing him to work full-time at IFOR, where he could be fully committed to peace and reconciliation. In fact, both he and Magda were named European co-secretaries of the organization. And they were given a very specific task.

Nelly Hewett: The idea was to create a center where groups of people from different backgrounds, different nationalities, different philosophies could have exchanges with one another and learn to understand each other and to reconcile with other people who are different from themselves.

This center needed to be somewhere easily accessible to travelers from around Europe. So, that meant the Trocmés had to leave Le Chambon.

Nelly Hewett: And finally in 1950, they left for good and settled in Versailles.

It had been 16 years since their arrival on the plateau. And as much as it was the end of an era, Le Chambon still had Edouard Theis, who stayed on as the director of the school, which was by this point called Collège Cévenole. He actually remained in the position until retiring in 1964. And the school itself continued on for decades until just a few years ago.

Nevertheless, this meant the Trocmés never fully disconnected from Le Chambon — they simply just moved on to the next project.

Nelly Hewett: They jumped from one fire to the other because my father was so creative and my mother too.

In addition to running this center outside of Paris — which they called the House of Reconciliation — they continued to travel around the world.

Nelly Hewett: Taking turns. A year dad, a year mother, a year dad, a year mother.

These trips were an opportunity to meet other activists and peace advocates, as well as share their ideas of nonviolence and reconciliation — which invariably meant sharing the story of Le Chambon.

Interestingly, one of Magda’s first trips was to India — the place where she and André had dreamed of going as newlyweds, to study nonviolence under Gandhi and observe the struggle for independence. Now, some 20 years later, she was arriving just in time to see the fruition of that struggle.

Magda Trocmé: Here I am in the capital of Hindustan, in the palace of the parliament, where they are about to vote on the Constitution of India.

Unfortunately, however, she was not in time to meet Gandhi. He had been assassinated the year before, and what she was witnessing was the kind of ugly chaos that often follows victory — a kind of ugly chaos not unlike Le Chambon at the end of the war, when anger ran rampant and once popular figures like André Trocmé became unpopular.

Magda Trocmé: We cannot let ourselves become discouraged simply because Gandhi did not possess every imaginable quality, that he didn’t always grasp social problems or because, in spite of abolishing the caste system, he sometimes didn’t take the side of the people against capitalism. If Gandhi had been a saint, a god, none or very few of us would have been able to follow him. But Gandhi set the best example possible: he pushed his faithfulness to an idea, a vocation, that of nonviolence, to its furthest possible limit. He died for this idea. It is up to someone else to step forward and continue this work.

A few years later, in 1956, Magda met someone who was doing just that — only it wasn’t in India, but rather the United States.

Magda Trocmé: The evening I spent in Montgomery with Martin Luther King taught me a great deal.

This was in the midst of the historic bus boycott. And she witnessed something rather amusing, at least in terms of how we view King today.

Magda Trocmé: Martin Luther King, a man the American public (and even his enemies) have considered the greatest religious teacher of our day, paused a number of times during his speech that evening. Why? To turn on the television set so he wouldn’t miss the last baseball game of the series!

For Magda, though, this kind of light-hearted moment was a reminder that amidst the deadly serious work of organizing — people still need to find time for enjoyment.

Magda Trocmé: This is what a modern saint looks like, especially those who are from the New World, who are preparing for a new world, and who take time to enjoy the pleasures and distractions of the world in which we live.

During her time in the American South, Magda also spoke before a black church in Tallahassee, something that was considered quite dangerous at the time — especially given that the local newspaper wrote a story with the sinister headline “white woman will speak to blacks.”

Magda Trocmé: It was one of the best experiences of my life. The church was full… I spoke as though I was being carried by the crowd.

And what did she speak about? Le Chambon of course. And this audience had no trouble relating to what the plateau experienced under Nazism. At that very moment, the white citizens council was trying to find a way to exempt Florida from federal anti-segregation laws.

Magda Trocmé: France in 1942, USA in 1957. Humanity is the same everywhere.

Not surprisingly, Magda had many issues with what she saw in the United States.

Magda Trocmé: Here was a flagrant contradiction in America: on the one hand, churches filled to capacity on Sunday mornings, and on the other, a horrific stock of A-bombs and H-bombs piling up, rampant financial imperialism and consumerism, and racial segregation.

Magda’s brilliance really shines through in her writings from this time period. She and André were such an incredible force for peace during the post-war years. They seemed to have their finger on the pulse of nearly every major world issue. For example, they were among the first to protest the dangers of nuclear power, getting arrested in 1958, as part of a sit-in demonstration at a power plant in Southern France.

That same year, André traveled to Japan to take part in a conference opposing the development of nuclear weapons. After seeing the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima a decade later, he didn’t mince words in equating it with the worst of what the Nazis had done.

André Trocmé: And to the right and to the left of the noisy bomb, I saw its hollow-eyed twins: the silent suffocation of concentration camps and the murder of human beings perpetrated by torture.

André also twice traveled to Vietnam with peace delegations, first in 1955 — right after the French surrendered — and again in 1965, in the midst of the U.S. war. Both times his aim was to urge Ho Chih Minh to enter peace negotiations with the South Vietnamese. Obviously, the communist leader wasn’t swayed to change course, as fighting continued for another 10 years. But André was certainly used to the difficulties of persuading guerrilla armies to put down their weapons.

Interestingly, he and Magda found a new approach to that problem in Algeria, which was not only at war with France for its independence, but also at war internally — between Christians and Muslims.

André Trocmé: When the Algerian war began, things became even more delicate. I was nonviolent. I could not approve of the terrorist acts conducted by the nationalist Algerians nor the repressive actions of the police and then the army ordered by France.

This time, instead of only advocating for a peace agreement, André and Magda focused on easing tensions through programs aimed at increasing literacy and employment. During the war with France, André moved into a slum (in the city now known as Skikda) and began offering free classes. Magda spent her time meeting with women and children.

André Trocmé: Revolutions make for unexpected encounters between groups of people who, up until then, have seemed to be irredeemably separated by political, religious and social barriers. Algerians and Europeans, Muslims and Christians stood side by side as they opened a school for mechanics.

In total, André and Magda traveled to some 16 or more countries — many of them twice — during the 1950s, their most active post-war period. Although the traveling and the speaking continued after they left the International Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1959, their final years together were much less of a whirlwind. They moved to Geneva, Switzerland, where Magda taught Italian at the university and André once again became the pastor of a church. This gave them some much needed stability and savings — as years of selfless activism had left them nearly broke.

Shortly after his retirement in 1970, André found out that he was going to receive a Righteous Among the Nations medal for his rescue work during WWII. The award, which is issued by the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, came as a shock to André. He didn’t like medals or being singled out and praised for his work. For one thing, he saw what happened on the plateau as a collective effort.

André Trocmé: Since I am opposed to decorations, I would have to refuse such a decoration. Why me? Why not the throngs of humble peasants of the plateau, who did as much and more than me? Why not my wife, whose conduct was much more heroic than mine? Why not my colleague, Edouard Theis, with whom I shared everything and all the responsibilities?

So he proposed an alternative, requesting that the award instead be given to the people of Le Chambon and the surrounding villages of the plateau. Yad Vashem agreed, making it the first time a place, rather than a person, received the award. Since then, only one other place has been honored by the memorial — a village in the Netherlands. And that’s among over 26,000 awardees and counting.

Sadly, André was unable to attend the ceremony, which he also requested take place in Le Chambon — rather than the Israeli embassy. He was in a hospital in Geneva, where he would die five days later, just weeks after his 70th birthday.

Nelly Hewett: It was a series of medical errors. His general condition was not very good. He died of an embolism after surgery.

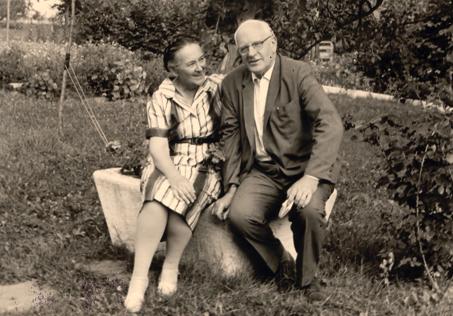

That’s Nelly, who was at his bedside just moments before he passed. Magda, naturally, was devastated.

Nelly Hewett: She was absolutely desperate. She said, “I lost my husband, the father of my children and my best friend.”

They were a tremendous duo, who had been through so much and were hoping to finally have some quiet time together, retiring maybe in Florence, which would allow André to immerse himself in fine arts — one of his numerous interests.

Nelly Hewett: They formed a very good team that way. She was the one who did the foot work. He did the conception and the dreamwork. And they needed each other because they completed each other that way. They were like two peas in a pod.

André, of course, knew this as well…

André Trocmé: My temperament makes me philosophize endlessly about life, death, people and things, and I tend to generalize and analyze everything. Fortunately, I married a woman who is firmly rooted in the present, in life and the lives of others, and she draws me out of my meditations, which can become stagnant and selfish.

Yad Vashem still gave André an individual award, which Magda received at his funeral in the church where he preached in Le Chambon. She, Edouard Theis, Daniel Trocmé and other major rescuers would have to wait over a decade to receive their own individual awards from Yad Vashem. That’s because the story and its central figures just weren’t that well known yet.

Perhaps the most detailed written account at that point was a short chapter in a 1969 book titled “Anthology of Holocaust Literature.” Its author was a former aid worker in the French internment camps. So, he had first-hand knowledge of the rescue. But even his version of the story was very short on details — and names. For some inexplicable reason, André is referred to as “Pastor M.”

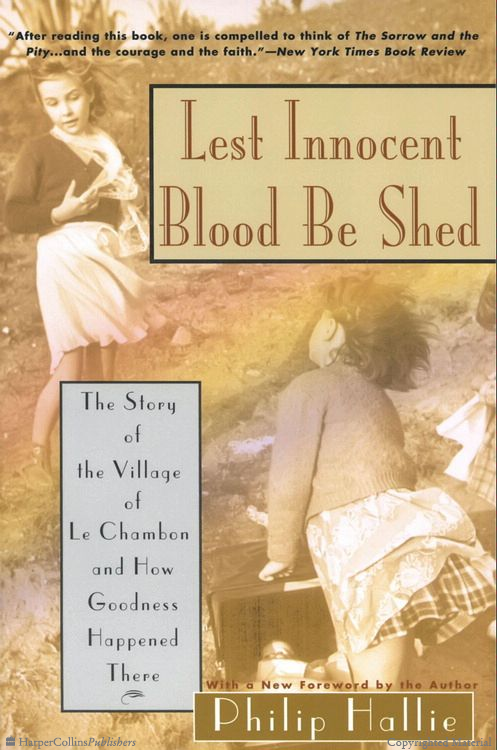

Nevertheless, this book found its way to Philip Hallie. Remember him? He’s the guy from the very beginning of the series, in part one, who was in the depths of despair, until he discovered the story of Le Chambon while flipping through the anthology I just mentioned.

Philip Hallie: I started reading, and my cheeks started itching and I reached up, and my cheeks were covered with tears, and I was reading about al little village named Le Chambon.

This was a man whose entire life — to this point — had been one long lesson in cruelty. Growing up, he fought with kids who hated him for being Jewish. During WWII, he helped level German cities, watching young men die at his feet. Then, he came home, and began his career as a scholar, studying the absolute worst things humans have done to one another. Over time, that led him to a rather cynical worldview. But then, he found the story of Le Chambon.

Philip Hallie: And I realized that this might be my salvation, that I could, by becoming interested in it, assimilate it, imitate it, mimic it, and maybe be saved.

So, he went back to France, found the village, tracked down whoever he could find, Magda, Edouard, anyone else still alive that had taken part in the rescue. Over the next few years, he wrote “Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed,” the first book on Le Chambon, and when it finally came out in 1979, it received serious attention — with reviews in the New York Times and elsewhere.

So, he went back to France, found the village, tracked down whoever he could find, Magda, Edouard, anyone else still alive that had taken part in the rescue. Over the next few years, he wrote “Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed,” the first book on Le Chambon, and when it finally came out in 1979, it received serious attention — with reviews in the New York Times and elsewhere.

Patrick Henry: I really think that Hallie’s book was a landmark book.

That’s Patrick Henry, who wrote his own book about Le Chambon called “We Only Know Men” over 25 years later.

Patrick Henry: It was one of the first books about the rescuers. It’s one of the reasons why the rescuers play such an important role in holocaust museums throughout the world.

Interestingly, it did more than just spread awareness to the wider public, it also managed to inform people closely connected to the story.

Mark Whitaker: It really wasn’t until Hallie’s book came out that even I knew the full extent of it.

That’s Mark Whitaker, Edouard Theis’s grandson.

Mark Whitaker: It just wasn’t in the nature of my grandparents or even their children to go around bragging.

At the same time, the book found its way to some of the Jewish refugees who had been taken in by Le Chambon.

Hanne Liebmann: When I saw the book advertised in the book review, with a picture… I said, “I know these people.”

That’s Hanne Liebmann, describing the New York Times review she and her husband Max came across.

Hanne Liebmann: And so of course we bought the book, and then I read it. Then I wrote a letter to Professor Hallie, and he used it in many occasions in his lectures he gave or speeches he gave. He then wanted us to come along with him repeatedly when he spoke.

Max Liebmann: Which we did.

Peter Feigl had a similar experience.

Peter Feigl: I was flipping through the pages of the Washington Post, and I mean flipping through them, and I had turned the page and suddenly realized I just saw something, “Chambon.”

It was another book review. So, of course, he went out and immediately bought a copy.

Peter Feigl: I began to read it and that helped a great deal in bringing back all the events and my participation in them.

Yet, for all the good that Hallie’s book did, it also created some serious problems. For one thing, it’s clear now that Hallie did not get the story fully right. In interviews just a few years after his book came out, Magda Trocmé said that Hallie had exaggerated a number of things. And today, Magda’s daughter Nelly still feels much the same way.

Nelly Hewett: He discovered the story, but he imagined many situations. He even recreated conversations.

The bigger problem for the Trocmés, though, was that Hallie had been infatuated with them — to the point of perhaps featuring them too prominently.

Patrick Henry: When the book came out in French, people were getting angry because they somehow thought that the Trocmé family talked to this man, Philip Hallie, and exaggerated the role that their family played, and made it look like they were the real key players.

Examining this controversy today, I have to say it seems a bit silly. For starters, anyone who knew the Trocmés, surely should have known better than to think they were the kind of people to self-aggrandize. What’s more, Hallie is pretty up front throughout the book about his adoration of the Trocmés — as well as the changes he was undergoing as a person by learning from them. In short, it should be clear to any reader that Hallie’s book is not the work of a dutiful historian, but rather a passionate philosopher.

Nevertheless, it’s understandable that people wanted a more complete version of the story to be told. And it only helped matters that more people — like the rescuers and survivors Hallie left out — were ready to speak about their memories of the war.

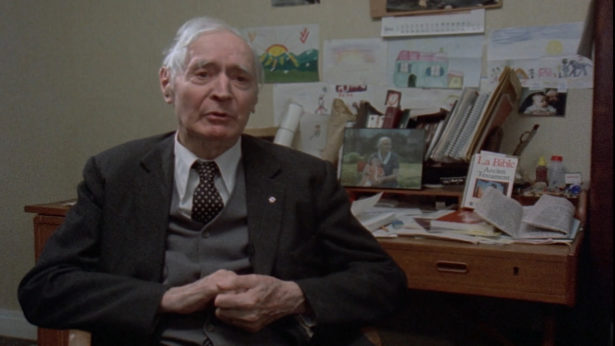

The first person to take on this challenge was a filmmaker named Pierre Sauvage. His documentary called “Weapons of the Spirit” was released in 1989, a decade after Hallie’s book came out.

Nelly Hewett: Pierre Sauvage tells a very straight story. He did good research, and it is still “the” documentary on the story.

Like Hallie, Sauvage had a compelling reason for wanting to tell the story of Le Chambon.

Pierre Sauvage: That’s where I had the good fortune to be born.

This is Pierre, speaking to me on the phone from his home in Los Angeles.

Pierre Sauvage: My parents met in Paris, and when France fell in 1940 they went south.

Both of them were Jewish, his mother having fled from Poland and his father from Germany.

Pierre Sauvage: They first went to Marseilles where they sought help from the Varian Fry Committee.

I actually mentioned Varian Fry in part four. He was an American journalist who ran another incredible rescue operation in southern France at the time.

Pierre Sauvage: But they actually were rejected, and my mother became pregnant and the big question was: Where should they go?

A friend told them about the plateau, saying that the people there were descended from the Huguenots — and that they might therefore be sympathetic to their plight.

Pierre Sauvage: You talk to survivors and they’ll always say, “Well, you know we were just lucky.” And I understand the emotional need to do that. But I’m convinced that the reality is that sometimes there were smarts involved as well. And it was simply, if you knew anything about Huguenot history, that was a logical door to knock on — a Huguenot door.

So Pierre’s parents soon settled in Le Chambon, which was not only the perfect place to hide, but also the perfect place to deliver their child.

Pierre Sauvage: It turned out to be a problem pregnancy. So this really complicated things.

Le Chambon, as it happened, had a very skilled doctor named Roger LeForestier.

Pierre Sauvage: He was committed to the rescue effort, and he had extraordinary medical skills.

He was the man I spoke about last episode, who was arrested by the Germans and later killed, but not before he played a role protecting Le Chambon from Nazi reprisals.

Pierre Sauvage: I am convinced that I was watched over and brought into the world more carefully than I might have been at any modern medical facility.

Amazingly, though, Pierre knew none of this until he was an adult.

Pierre Sauvage: My parents chose after the war to put all this behind them. And not only was I not raised with stories of Le Chambon, but my parents even hid from me the fact that I was Jewish.

The only reason they told him was because he was going to Paris, where he would be staying with some family.

Pierre Sauvage: And I think my parents knew that the secret would no longer be kept, so they chose to tell me — which was a smart move.

Even after finding out, though, Pierre was not particularly interested or all that shocked.

Pierre Sauvage: Basically what my parents did is tell me the facts, but they also told me it was not important. And for many years I accepted the fact that it was not important.

That changed, however, as he grew older and met his wife, who also happened to be Jewish. Eventually, they took a trip together to Le Chambon in the early 1980s.

Pierre Sauvage: And I met other people there, and I realized what an important story this was.

He knew about Hallie’s book at this point, but immediately saw there was more to the story yet to be told.

Pierre Sauvage: I realized I really wanted to capture these people. I wanted to show their faces. I wanted to provide their testimony.

Before long he was interviewing many of the core figures of the rescue effort, including Magda Trocmé and Edouard Theis.

Edouard Theis (in French): Jesus did what he said, “You shall love the Lord of your God, with all your heart, your soul, your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.”

That’s Edouard speaking in perhaps the only recording that exists of him. Sitting in front of pictures of Gandhi and MLK, he explained that Christianity, to him, boiled down to one thing: loving God and your neighbor as you love yourself. Sadly, Edouard passed away not long after this interview. He was 85 years old. But according to his daughter Jeanne, he would have appreciated the film.

Jeanne Theis Whitaker: The film pays tribute to other people in the town, not just the two pastors. He thought that was very important because it was the whole town.

Pierre Sauvage: What the Trocmés did, which is extraordinarily important, is help steer the community, but it’s not as if they created this momentum. The momentum derived from something much much deeper than that. It really was, as Magda puts it in my film, “It was a consensus,” and it was a consensus that had deep roots.

As a result, Pierre spoke to a number of people who had not crossed Hallie’s radar — rescuers like Madeline Dreyfus, who saved at least 100 children during the war. At the same time, he also confronted one of the plateau’s first real opponents.

Pierre Sauvage: I got the testimony of the Vichy official who actually went to Le Chambon during the war.

Georges Lamirand. Remember him? He was the Vichy Minister of Youth who came to Le Chambon expecting a grand reception, but was confronted with the fact that the village was hiding Jews.

Pierre Sauvage: I came to realize that one of the reasons he agreed is that he had nothing on his conscience. He was convinced that he hadn’t done anything actively wrong.

Looking somewhat annoyed at Pierre, he actually tries to explain that he never denounced Jews and wasn’t involved in the roundups. He even goes so far as to say “I have many friends who are Jewish.” And while that may have been true, he was undoubtedly a classic example of the banality of evil.

Pierre Sauvage: One thing I certainly lacked was a villain. And the reality is, if I had been able to dig up Hitler living to a ripe old age in some place in Argentina, I would have been happy to have the scoop. But he really would not have been the right villain for me because the right villain for me was the villain of omission, not the villain of commission. This was a story about people who couldn’t look the other way.

Far more uplifting than that, though, was Pierre’s inclusion of refugees who had been helped by the plateau — people like Peter Feigl, who in this clip is shown returning to Le Chambon for the first time since he was a teenager.

Peter Feigl (in film): It evokes a feeling of gratitude, a gratitude that I can appreciate today and I wasn’t even aware of when I was 14.

Even more amazing than that return scene however was something that happened to Peter after the film was released.

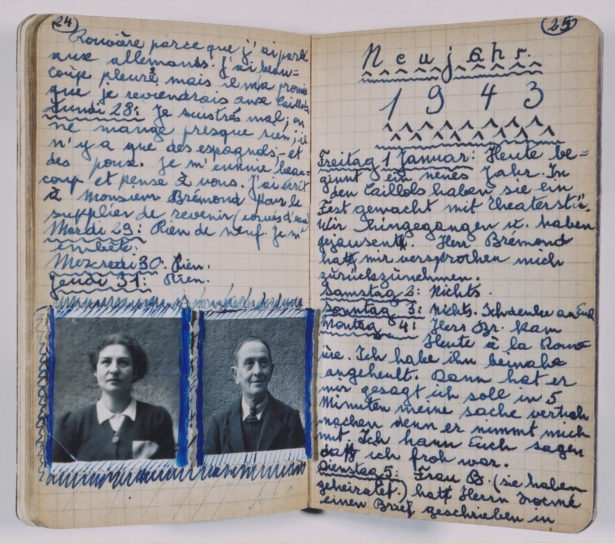

Peter Feigl: I received a letter from a man in Paris asking me if I was the Peter Feigl who wrote a diary dedicated to his parents.

If you’ll recall, Peter had been writing in diary up until Daniel Trocmé took it away from him for safety reasons.

Peter Feigl: And I pretty much had forgotten that I had written this. I occasionally said “I could have sworn that I had a diary that I wrote originally, but did I really write it or is this a figment of my imagination?”

The man who contacted him about it said he had found it in a flea market after the war.

Peter Feigl: He said “I am a collector of such memorabilia, and by the way I published your diary in France in 1976 because I had assumed that you perished.”

But rather than return the diary out of kindness, the man made Peter buy it back. He has since donated the diary to the U.S. Holocaust Museum, which regards it as an important primary source account of a Jewish child’s life in France during the war. But that’s just one example of the film’s impact. It also helped other former refugees reconnect with their past.

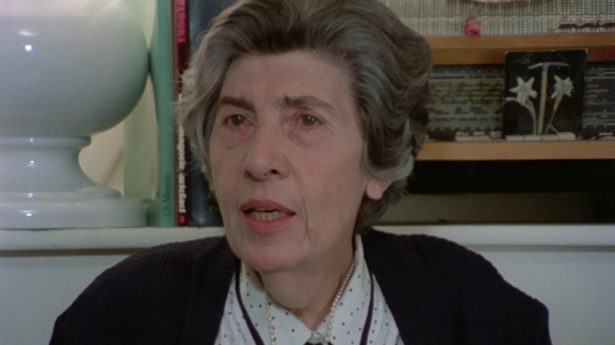

Renée Kann Silver: I had never really spoken to my husband about the full extent of my experiences.

That’s Renée Kann Silver, who was just a young child during WWII. And the experience had been so traumatic that she put most of it out of her mind — until one day, in 1989, when she came across an article in the New York Times about “Weapons of the Spirit.”

Renée Kann Silver: So I said to my husband, “There is a film being made about a town where I think I might have spent some time.” And he went with me.

So they went to see it together, and at one point in the film…

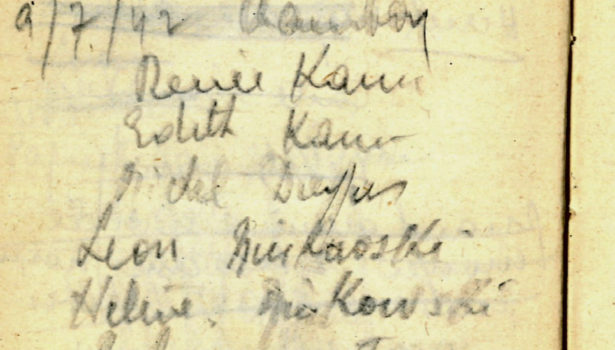

Renée Kann Silver: Pierre Sauvage speaks to a Mme. Dreyfus, whom I definitely did not recognize because this is 40 years later, and he said to her “I understand you kept a little notebook.”

This was so Madeleine could keep track of where all the children were hidden — something she admitted to Pierre was quite risky.

Renée Kann Silver: Anyway she opens this notebook on the screen, and I saw my sister’s name and my name and our address and my sister’s date of birth, and it goes on and she turns pages and my name appears again. And I let out a scream I have never in my life screamed like that.

It was an incredible turning point for her.

Renée Kann Silver: That’s when I first reconnected, and the first time I realized that I had not been part of something shameful but a part of something extraordinarily beautiful and worthy.

While “Weapons of the Spirit” won many awards — including one shared with Ken Burns — stories like Renée’s are what Pierre considers his greatest honor.

Pierre Sauvage: Nothing moves me more and pleases me more than when another survivor of Le Chambon comes out of the woodwork. I can’t tell you how gratifying that is.

And in 1992, not long after the film was released, there was a large gathering in Le Chambon, which is now referred to as “the colloquium.”

Renée Kann Silver: It was a gathering of the survivors and of course the people of Le Chambon and members of the Resistance who had all been very active in that area.

At one point, everyone got together and sang the French version of Auld Lang Syne.

Renée Kann Silver: It was an extraordinary experience. It was very very very moving.

The colloquium also yielded an important resource — a 700-page volume containing the entire proceedings of the three-day gathering, where many people involved in the rescue operation spoke for the first time.

Nelly Hewett: All the people who thought they had been forgotten by Hallie came out.

That’s Nelly again.

Nelly Hewett: They needed that to show they had done something too. And they were right because Hallie made it sound as if there was only Le Chambon and Trocmé. It revealed many many people did a lot a lot of things.

In fact, André was barely even mentioned at the colloquium, despite his role as a charismatic catalyst, organizer and orator.

Nelly Hewett: He was like forgotten.

It may seem strange to leave out someone who is so central to the story, but as Nelly said…

Nelly Hewett: They had to discover the other parts of the story.

And while that was happening, Magda Trocmé was spending her final years arranging André’s memoirs and writing her own. When she passed away in 1996 at age 95, her papers — when combined with André’s — total around a thousand typed pages. And, together with the colloquium, they offer researchers and historians about as complete a story as there can be of an unplanned, largely clandestine resistance and rescue operation.

Nelly Hewett: Without a paper trail, stories get lost. And so, I think Chambon is documented now.

There’s probably been a dozen or so books written about it in the last 20 years. And I’ve relied on a good number of them to make this podcast. If you check out the show notes on Waging Nonviolence you’ll see the long list for each episode.

But, as we wrap this one up, I’d like to come back to Philip Hallie, the man who put the story of Le Chambon on the map. Knowing how much it changed his life — on a deeply personal level — I couldn’t help but wonder what he thought about everything that happened after his book came out.

And it turns out, the criticisms — the fact that the Trocmés weren’t entirely pleased and other people felt left out — they weren’t really on his mind. Instead, Hallie found himself grappling with something much bigger.

Philip Hallie: I said to myself, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. Something in your heart resents the village. Something in your heart resents the village.” They didn’t stop Hitler. They did nothing to stop Hitler.

That’s Hallie talking about what happened after his book came out, after he thought he had undergone a conversion.

Philip Hallie: A thousand Le Chambons would not have stopped Hitler. It took decent murderers like me to do it. Murderers who had compunctions, but who murdered nonetheless to stop him.

So, that conversion he had experienced — it seems it didn’t stick. Hallie’s old demons, his thoughts on cruelty and human nature, had returned. And they were threatening to tarnish everything he had come to learn and love about the story of Le Chambon. But how he grappled with these doubts — ones that maybe you yourself have had as you’ve listened to this series — it tells us a lot about what the story of Le Chambon really means.

So, join me next week, for our final episode, as we explore the greater lessons of Le Chambon and its greater relevance to the world today.

—

On the next episode:

Pierre Sauvage: The issue of whether a community, a city, an area, a state, should be a place of sanctuary, that’s a political decision. But once that political decision has been made, then the question is, well, “What is there to be learned? Are there other examples?” Le Chambon really is a singular example of a whole community that turned itself into a place of sanctuary.

Credits

City of Refuge was written, edited and produced by Bryan Farrell.

Magda and André Trocmé were performed by Ava Eisenson and Brian McCarthy.

Audio of Philip Hallie came from the 1988 documentary “Facing Evil,” produced by Moyers & Company.

Audio of Hanne Liebmann, Max Liebmann and Peter Feigl was derived from the following interviews conducted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

- January 19, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- January 19, 1990 – Max Liebmann

- March 28, 1990 – Hanne Liebmann

- March 28, 1992 – Max Liebmann

- June 2, 1998 – Hanne and Max Liebmann

Special thanks to Pierre Sauvage for the clips of Edouard Theis and Peter Feigl from his film “Weapons of the Spirit.” Pierre is working on a 30th anniversary edition that you can learn more about at his website: Chambon.org.

Theme music and other original songs are by Will Travers.

This episode also featured the following songs:

- “Quiet” by Audionautix (license)

- “The 49th Street Galleria” by Chris Zabriskie (license)

This episode was mixed by David Tatasciore.

Editorial support was provided by Jessica Leber and Eric Stoner.

Our logo was designed by Josh Yoder

Resources

This episode relied on the following sources of information:

“A Good Place to Hide” – a 2015 book by Peter Grose

“Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed” – a 1979 book by Philip Hallie

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“My Long Trip Home” – a 2011 book by Mark Whitaker

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth

“Tales of Good And Evil, Help and Harm” – a 1997 book by Philip Hallie

“Weapons of the Spirit” – a 1989 documentary by Pierre Sauvage

“We Only Know Men” – a 2007 book by Patrick Henry

The following sources contain interviews with, or writings by, Magda and André Trocmé that were adapted for use in this episode:

“Magda and André Trocmé: Resistance Figures” – a 2014 book edited by Pierre Boismorand and translated by Jo-Anne Elder

“Portrait of Pacifists” – a 2012 book by Richard Unsworth